It may have been a mere coincidence that Kenny Knauer died on Memorial Day.

Or not. Because he was, if nothing else, a memorable character.

So was “Ke Knuck.” And “The Governor.” And “The Grand Marshal.” And “Kenny Mike”...

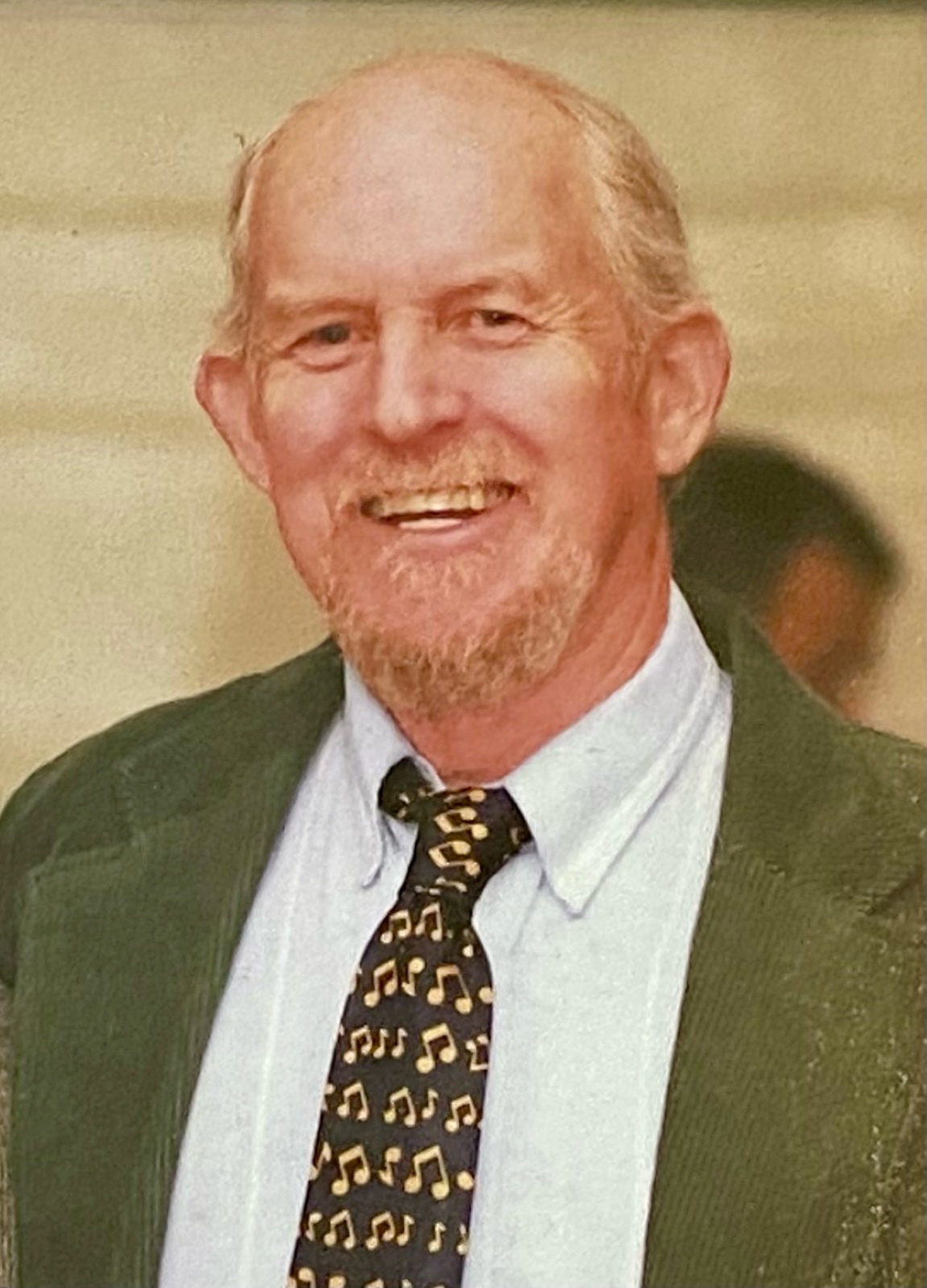

Those are some of the nicknames by which family and friends knew Kenneth Michael Knauer, who passed away Monday, May 27, in his Springfield home on the edge of Phelps Grove Park at age 80.

Many who didn’t know Kenny personally by name nonetheless recognized him by his distinctive appearance — flowing red beard and shamrock-green garb, like an outsized leprechaun — in 40 annual St. Patrick’s Day parades here, serving as grand marshal in 2006. Or they knew him by the gravelly timbre of his voice as he hosted two decades of the Friday night “Jazz Excursions” program on local public radio station KSMU.

Or they encountered him as an enthusiastic volunteer worker or thoughtful board member for several civic organizations. Or as a fervent member of audiences at musical performances of all genres. Or as a persistent promoter and advertising salesman. Or as an entertaining conversationalist who could discuss current events, explain philosophical dogmas and spin windy tales with equal aplomb.

A fortunate few knew him as an empathetic ally offering encouragement to overcome addictive demons.

Kenny Knauer was all those things, and more.

His wife, Marti, knew him as her “sweet, tender, compassionate, loving” partner in life.

He knocked her off her feet — literally — 43 years ago, shortly after she’d earned a degree in the fledgling gerontology program at Southwest Missouri State University (now MSU) and signed on as a social worker at the Mercy Villa nursing home.

“Kenny was taking his mother to visit his aunt, who was a resident there, and we collided at a corner in the hallway,” Marti recalls. “He had to pick me up off the floor. I said, ‘Well, we might as well introduce ourselves.’ And that’s how we met.”

Kenny often called her by her given name, Martha. From an early age, he often called himself Ke Knuck, pronounced “KEE Kuh-NUK.”

Arrived in the world ‘on top of a boxcar’

His older brother, longtime Springfield attorney Link Knauer, recalls the first time he heard it:

“Kenny always had a vivid imagination. When he was about 4 or 5, someone mentioned that a woman we knew was going to the hospital to ‘get her baby,’ because that’s how babies get here, y’know. But Kenny said, ‘Well, I didn’t.’

“So we asked how did he get here? He said, ‘I rode a train from California on top of a boxcar with my friend Tommy Turtle as my companion.’ He also revealed that his actual name was Ke Knuck. And he maintained that position as long as he lived.”

Kenny’s younger brother, Kelly, retired from a career as a senior publications editor with TIME, Inc., notes that Kenny “still was receiving Christmas presents addressed to this mythical figure” in recent years.

“His beguiling tales followed a predictable arc,” Kelly says. “First would come the simple statement of a sensible fact. Then the mighty flow of words began, and the basic story would be adorned with a flotilla of anecdotes. These were designed to lend a veneer of credibility to what gradually became an outrageous tale that might include any of a host of colorful characters: the Marx Brothers, Red Foley, Red Chaney, Buff Lamb, David Leong, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, mermaids and palm-readers and lion-tamers…”

Tall tales that sometimes proved true

Some outlandish stories involving Kenny really were true. Terry Meek — his oldest friend, having been born the same week as Kenny in the former northside St. John’s Hospital and attending kindergarten at Rountree Elementary School and all 12 grades at St. Agnes parochial schools with him — recounts an adventure in their senior year in high school that was prompted by a Catholic Youth Conference convention in Chicago attended by some female classmates:

“Kenny and I, and another friend (Steve Swift), decided we were going to drive up there for the weekend to see the girls. Kenny and his brothers slept on the third-floor of their big house in Meadowmere Place, and their mom almost never went up there. So we said that we were going to the movies on Friday night, and that we were going fishing, early to late, on Saturday. Then we got into Kenny’s ‘56 Ford and headed off to Chicago.

“We drove all night, but just as we got into the Chicago city limits the engine in Kenny’s car blew up. There we were, with about 40 bucks between us, AWOL in Chicago and the engine is dead. We pulled into a service station and asked the attendant how we could get the car towed somewhere. The guy said, ‘I have a pickup truck with a tow bar on it, and I can tow you all the way back to Springfield.’

“It was going to cost much more money than we had — something like a hundred and a half. We gave him our 40 bucks and said, ‘When we get to Springfield, we’ll find the rest of the money to pay you.’ For some reason he trusted us and agreed to do it.

“There was no room to ride in the cab of the truck with him, and the back of his truck was full of tools and stuff. Our only option was to ride in the towed car, two in the back seat and one in the front. We called the front the suicide seat because we figured that if the car came loose, the guy sitting in the front would get killed and the two in the back might survive. So we took turns riding in the front, climbing back and forth over the seat, all the way to Springfield.

“We got back to town early Sunday and dropped off the car at Kenny’s house. But then we had to round up the rest of the money without telling our parents because we were still on the sly. The other two sneaked back into the house and went upstairs to the beds, and I went with the guy in his truck to find money from friends. We got $20 here, $10 there, a bunch of quarters somewhere else — and somehow came up with enough to pay off the guy.

“And we never got caught.”

Of life in a prominent family — and ant lions

The three Knauer brothers had two older sisters, all offspring of Lincoln and Marcella Knauer. The girls grew to lead very active adult lives, especially in community service. The eldest, the late Jan Knauer Horton, was best-known as the first president of the Community Foundation of the Ozarks; and Roseann Knauer Bentley is a former state senator and Greene County commissioner.

“My sisters probably viewed me as a pest and a nuisance,” Link says, “and so when we were young, I sort-of viewed Kenny as a pest and a nuisance, because that’s what older siblings do.” But Link came to recognize his kid brother’s inquisitive mind.

“Kenny got interested somehow, some way, in a little critter called an ant lion. Whoever heard of them? Well, Kenny did, and he was finding them all hours of the day and night out in the yard. He’d look for ant lions [sometimes called doodlebugs] and he’d show them and explain them to us.

“He’d find where there were ant hills, and in that area there also often were little pits in fine sand. They were traps. And at the bottom of that pit, waiting for a curious ant, was an ant lion. They were scary-looking little creatures with pincers, waiting down there for an ant to come sliding down. They’d have a tussle, and the ant lion usually won because he was bigger.

“I never knew anyone else who knew about ant lions, but Kenny did.”

Exploring business, music and worrisome habits

Following high school, Kenny enrolled at Mizzou in Columbia for a few semesters, then transferred back to Springfield in 1961 to attend the then-new Breech School of Business at Drury College (now University). There he met Rick Matz.

“We both were only marginally invested in our studies,” Matz now admits. “We were more interested in finding out which taverns in Springfield were lax on documentation of legal drinking age.”

In following years, Matz says, “we traveled the ways of several different lifestyles together.” Not all those lifestyles were healthy. However, with regard to life in general, Matz emphasizes that “Kenny’s consistent guiding principle was ‘Do No Harm.’”

At one point, Kenny migrated to California for a while. “He had no real experience in business, much less business management, but he somehow got a job managing a band out there,” says Link. “He was very knowledgeable about music and the music scene.”

At Drury, Kenny also met Bob Shaw. “We got to know each other a bit,” Shaw says, “but then, due to my less-than-sterling academic record, I went into the Army for three years. When I came back, we got reacquainted through the local ‘alternative community.’”

Shaw, who became an elementary school teacher and served in classrooms here for more than two decades, kept some distance between himself and Kenny over the next few years when Kenny’s lifestyle habits became worrisome. But after Kenny saw Rick Matz become involved with recovery support groups and achieve abstinence from mood-altering substances, Kenny chose to follow that path also.

“We really reconnected at that point,” says Shaw. They shared a love of music, and Shaw was putting on monthly “house concerts” at downtown venues, featuring acoustic musicians. “Kenny would help me. He would take tickets, haul equipment, just anything we needed.”

‘The Governor’ showed an interest in current events

Shaw and Kenny also shared an interest in current events. “Kenny was very well-read. You could talk to him about most any topic, and he would have some knowledge about it, especially government and national and international events.

“For about three years, I would pay for six months of the Sunday New York Times to be mailed to us, and the next six months he would pay for the Sunday Washington Post to be mailed. During the week we would trade off sections. It kept us well-informed on a lot of stuff.

“He had a phenomenal memory. And we had fun with vocabulary. When we discussed things, we’d throw in a word here and there to see if the other one knew it, or just delight in the use of the word,” Shaw says.

Something else that traced back to his Drury days was Kenny’s nickname of “The Governor.” Exactly how it got hung on him is hazy, but he embraced it. For several years his car bore a personalized plate that read “GOVNOR.”

Another longtime friend with another extraordinary adventure story involving Kenny is Tim Goodrich, an original member of the zany local band The Garbanzos. He tells of a trip that he and fellow Garbanzo member John “Indian” Ehlers took with Kenny to Brazil.

“We get on the plane to fly to Rio de Janeiro, and we find out that Kenny has no money with him. But he says not to worry, that he has some sort of tax refund thing coming, and he can get it in Rio. I think it was supposed to be wired to him or something, but I don’t think he ever got it.

“It was Carnival time in Rio, and we had a great time. I had taken my guitar along, and John had his violin and washboard. Somehow Kenny ended up losing Indian’s washboard, and he felt really bad about it.

‘Where’s Kenny?’

“We also had booked flights to Manaus and Belem to check out the Amazon region. On the day we were supposed to fly to Manaus, Kenny was nowhere to be found. John and I went on ahead, and Kenny eventually showed up.

“Then we fly to Belem, and the same thing happens. When he catches up this time, he’s lost his shoes and his watch — I’m not sure how. The locals started calling him ‘Barefoot Papa Noel’ because with his long beard they said he looked like Santa Claus.

“From all that came a quip that became famous: ‘Where’s Kenny?’ As years went by and the story got told around, it became the universal question among his friends — ‘Where’s Kenny?’ And when I traveled, wherever I’ve had a guide, at some point I’ll prep him to say “Where’s Kenny?’ and then point my phone at him and record it. I’ve got videos from Morocco, from Turkey, from Spain, from all over, with locals asking ‘Where’s Kenny?’”

Goodrich, who early on worked as a brakeman/switchman for the Frisco Railway here, eventually studied computer science at SMS and lives in San Francisco, where he has worked as a programmer while continuing to play music. But he’s returned regularly to his old hometown, and usually met Kenny for catch-up conversation over meals at Mexican Villa.

“I’ve always enjoyed his ability to tell a story,” Goodrich says of Kenny. “And he does it with that look, a twinkle in his eye.”

Others agree. One is Chris Whitley, who was a Springfield News-Leader reporter when he first met Kenny in the late 1970s at the former Munchies restaurant in downtown Springfield.

“Now, there’s ‘meeting Kenny’ and there’s ‘getting to know Kenny,’” Whitley says. “I cannot say that we were friends at first; we were acquaintances. I’d see him at Munchies — he was part of the landscape there — and I thought he’d be an interesting guy to know. But that didn’t happen for a while.”

The birth of the St. Patrick’s Day parade

The catalyst for Whitley’s getting to know Kenny was the St. Patrick’s Day parade.

“Kenny and Marti came to the newspaper to promote the parade, and I was assigned to do the story,” Whitley says. “I just had a fantastic time interviewing them, and the story ended up on the front page. We were fast friends from then on. Kenny decided I was an ally, so I was pretty lucky to be taken into his orbit.”

The St. Patrick’s Day parade grew out of David Trippe’s establishing in 1980 what became a popular Commercial Street tavern called the Buffalo Bar.

“I opened it on St. Patrick’s Day, and it was horrible weather — the wind was blowing, it was sleeting, I didn’t have any heat, I didn’t have any furniture,” Trippe recalls. “Kenny was a member of what they called the Independent Marching Band, and they’d marched from one end of the Northtown Mall parking lot to the other, and then came to the Buffalo to celebrate St. Patrick’s Day even though some people said it was colder inside the bar than it was outside.

“We decided that the next year we would put on a real parade, and Kenny absolutely loved the idea. He was involved from the very beginning. We started out on a shoestring budget, and barely made enough money to put it on. But we wanted it to be a ‘people’s parade,’ and never charged a penny for anyone to be in the parade.

“But as it grew, from Commercial Street to Park Central, it became more and more expensive to put it on — you have to pay for insurance, you have to pay for the police who are there. So Kenny and I would get together and go over a list of who we needed to talk to for donations.

“Now, I don’t want to use words like ‘badgered’ or ‘annoyed,’ but Kenny would talk to potential donors tenaciously — just Kenny being Kenny. We made him chair of the parade finance committee, our fundraising committee. He was great at it, getting contributions and selling ads for the parade booklets. He knew a lot of people. He did a wonderful job of helping put together the money to keep the parade going for 40 years.

‘He couldn’t wait to get dressed up’

“He loved to go on the local TV talk shows in full regalia and promote the parade. He couldn’t wait to get dressed up. He loved participating in the parade with the groups — doing the infamous ‘Cockroach Maneuver,’ being part of the Cobras. Some people thought he was always the Grand Marshal, but officially he was it only that one year (2006).”

The parade was suspended for a couple of years due to COVID. When it resumed, the parade organization duties were handed over to the Downtown Springfield Association, which had been assisting for many years. “We decided it was time for us old folks to step aside and let the youngsters take it over,” Trippe says. “Kenny would be OK with that.”

Marti agrees. Kenny had been dialing back as his health declined. He retired from the KSMU radio show, and he and Marti no longer camped for most of the month of September in Winfield, Kansas, where for four decades they’d attended the annual Walnut Valley Festival that features bluegrass and other genres of acoustic music.

However, longtime friendships remained vibrant. Local pals visited frequently, and an 80th birthday party that Marti organized drew more than 130 guests.

A special treat was a visit in March by members of the Comfortable Shoes camping crew that were part of Kenny and Marti’s “family” at Winfield. “Thirteen of them came here and serenaded Kenny,” Marti says. “One even wrote a song for him. It was so sweet.”

One of the last visitors before Kenny died was Janet Hicks. She had known him since the early 1980s — “I was part of the Independent Marching Band shenanigans,” she admits — had worked with Marti at the Springfield-Greene County Health Department, and had camped with them at Winfield several years.

She also has helped in recent years with Marti’s personal mission of preparing Wednesday lunches for distribution to unsheltered locals.

“Kenny was always the most caring, kind and sweetest person there ever was — a perfect gentleman always,” she says. “He was very involved as a volunteer at Artsfest. One time I took my mother there. She didn’t know anybody, but we met Kenny in the crowd. And he just took to her like they were best friends. And for years after she would say, ‘Remember that guy we talked with at Artsfest…’ He made such an impression on her. You’d think they’d known each other forever.”

Many others have fond memories of talking with Kenny — although former journalist Whitley laughs when he recalls bumping into Link Knauer a few days after the interview with Kenny and Marti at the newspaper.

“I said to Link, ‘Hey, I was talking to your brother the other day…’ But he interrupted me and said, ‘No you weren’t.’ I said, ‘What?’ And Link said, ‘You weren’t talking to my brother — you were listening to him.’”

Whitley says he’ll “always remember just how entertaining a conversationalist Kenny could be. He always seemed to be carrying a satchel of some sort, filled with newspapers, magazines, clippings, scissors with which to dispatch more clippings from publications, pens and pencils and crossword puzzles and all sorts of other entertaining things. He could keep you going as long as you’d allow.

“Kenny was a highly intelligent guy, tremendously articulate. He had no stomach for scoundrels, but a wonderful heart.”

‘The Kenny Knauer Kaleidoscope’

Mike Smith, retired longtime stalwart at KSMU, also remembers Kenny’s cache of local and national newspapers. “He was eager to pull out and discuss a clipping from any of those papers’ previous day’s editions. When he shared clippings and stories that interested him, it was like you were given a special instrument with which to view the world — the Kenny Knauer Kaleidoscope.”

Kelly Knauer notes that, in middle age, Kenny took up haiku, the Japanese poetic form that limits writers to 17 syllables. “Perhaps it was a form of apology,” he jokes, referring to his brother’s legendary long-windedness.

“But whether he delivered a 20-minute stemwinder or a revelation in 17 syllables,” Kelly says, “one thing was clear: We’re not liable to hear his like again.”

No formal funeral service is planned. However, Marti has reserved the pavilion at Phelps Grove Park for July 14, and is planning to host a gathering there including potluck food and music. She will announce details closer to the event.

Here is a partial list of Kenny’s volunteer activities:

- Two years as an Americorps reading tutor

- Team leader with neighborhood cleanups

- Organized the Phelps Helps concert series at the Art Museum

- Served on the Jordan Valley Park advisory committee

- Emcee’d the main entertainment stage at Artsfest

- Served on the Founders Park steering committee

- Presided over the Max Hunter music stage at the MSU Ozarks Celebration Festival

- Active with Friends of the Garden and the Tree City USA organizations

- On the Vision 20/20 committee

- Mentored others toward sobriety