WEST PLAINS — Nearly a century ago, the hopes, plans and dreams of dozens of people disappeared from West Plains — the Howell County seat, located around two hours east of Springfield — and into the inky night. Those lives, frozen in time, never knew that their plans didn’t work out as they expected — but their friends, family and the community at large were left with the agony of mystery.

The mystery, of course, isn’t what happened: It’s well-known that an explosion and resulting fire during a dance on April 13, 1928, destroyed Bond Hall, tragically taking 39 lives with it.

Some speculated it was a plan for insurance money, botched and ill-fated on the night of a dance attended by many young adults in the West Plains area. Another theory, among a number of several, suggested it was a form of punishment for the evil sin of dance.

Regardless of why, it’s still unknown just why or how the building went up in the blaze.

“Above the wild shrieks of the imprisoned victims could be heard the roaring of flames that soon enveloped every person in the firetrap,” printed the Howell County Gazette in the days after the event. “The cries soon turned into moans and then all was still — their souls had returned to their maker.”

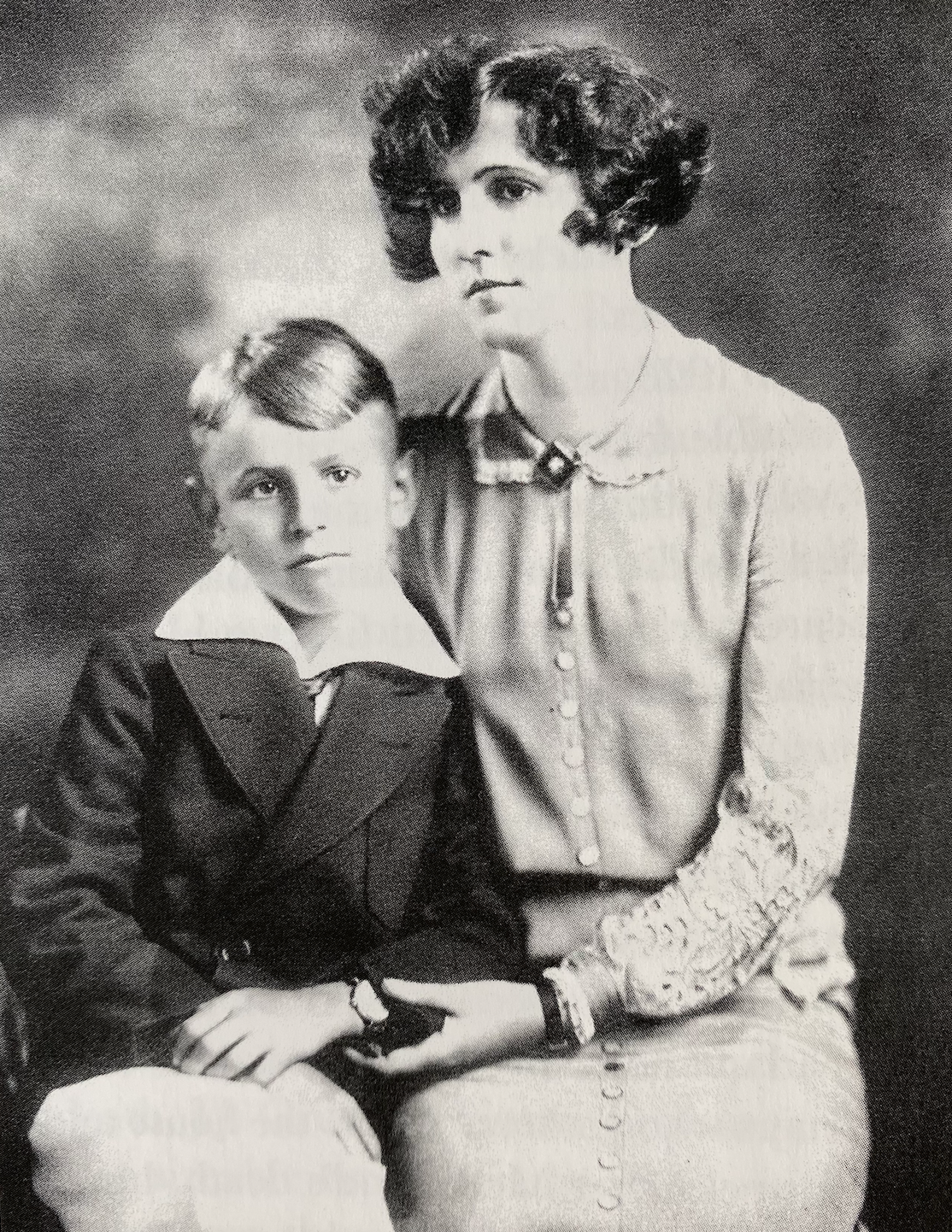

Each of the lives cut short represents a tragic loss and one that altered more lives than those who died. But one who especially caught my attention when doing some research about the blaze was Mary Katherine “Kitty” McFarland — not specifically for her death, but for her life.

Kitty was only 31 when she died that night, and left behind a young son. Although she didn’t know her years would be short, she didn’t waste time with her life: She quickly made a name for herself in the business world at a time when women traditionally didn’t work outside the home. While her contributions to the West Plains community were varied, a key example was that she was said to be the first — and perhaps at the time, only — licensed female embalmer in the state of Missouri.

‘Quite a lady'

“I think Mary Katherine McFarland was quite a lady,” says Jim McFarland, her grandson, who still lives in the West Plains area today. “My dad named his first daughter after her.”

On the anniversary of her untimely death, let us let her live again.

McFarland Undertaking Company began in West Plains in the late 1800s. It was founded by John Henry McFarland, Kitty’s father-in-law, but it appears that Kitty quickly became involved after her marriage to Ray McFarland in 1914.

One example: In 1921, news accounts shared her efforts to begin a factory for fashion-forward burial robes in West Plains.

“West Plains has a new industry,” printed the Springfield Leader in September 1921. “Mrs. Kitty McFarland, funeral director and embalmer, who is associated with her husband, R.L. McFarland and his father, J.H. McFarland, in the McFarland undertaking company in West Plains, has opened a factory in connection with the company’s business on West Main street, where she will design and manufacture fashionable burial robes for women and children. She will manufacture both for the McFarland company and for wholesale trade.

“The idea for such a factory was suggested to Mrs. McFarland by the trouble she found in pleasing patrons of the McFarland company with the usual type of burial robes on the market. She constantly has been called upon to buy material, design and have made by local dressmakers burial dresses for patrons who want for their dead something more attractive than the somber ready-made burial robe. Therefore she has fitted up a dressmaking shop on the second floor of the McFarland establishment and is keeping experienced dressmakers busy turning out the dresses which she herself designs.”

That effort was also covered by the West Plains Journal, which added a bit more info:

“Mrs. McFarland has been to the large cities studying the styles and will put on the market only garments of the latest styles and best workmanship.”

Tragedy strikes twice in 1923

It is difficult to imagine the heartache that entered Kitty’s world in July 1923. That month, she became head of the entire company when her father-in-law and her husband died within three weeks of each other.

Health issues caused the elder McFarland’s demise, described by the Mountain View paper as “spleen trouble” following blood poisoning, while her husband was killed in a car crash.

“The Rev. Sam L. Roper, pastor of the Presbyterian church was in charge of the service, which was conducted very much like the service the pastor held four weeks ago for Mr. McFarland’s father, J.H. McFarland, who died after a long illness,” printed the Journal. “A quartet composed of Dr. J.F. Park, Roy Hill, Dr. Claude Bohrer and Charles Bohrer sang ‘Summertime, Somewhere,’ ‘A Beautiful Land,’ and ‘Home At Last.’ These numbers were given at the elder McFarland’s funeral.”

I didn’t see an article in the weeks that followed assuring that business would go on unchanged. What I did see, however, was a continuation of its advertisements, which regularly ran in the West Plains paper. Even before the death of the McFarland men, its primary line said: “Lady Attendant on All Occasions.”

Perhaps no assurance was needed that things would continue as they had. They simply knew they would with Kitty at the helm.

Despite the tragedy the family experienced, it appears that the next few years were great for the unexpected business leader. Professionally, her business saw continued advancement: Small news “items” in the local paper regularly mentioned she was in places like Springfield, St. Louis and Van Buren on business. At one point, she drove back from St. Louis with a new limousine funeral car.

“This car, which is especially built and mounted on a Dodge chassis, takes the place of the old fashioned hearse and gives the McFarland company the latest thing in funeral equipment,” printed the Journal in 1926.

That drive was the year after she was elected as the first president of the Ozark Embalmers and Funeral Directors Association. Its initial meeting was held in West Plains in 1925, and featured a keynote speech that spoke of signs of the times:

“In his address, Prof. Williams said that if he lived in the Ozarks he would quit his profession, as the country seemed to be the most healthful. The speaker dwelt at length on the importance of embalming and its relation to the health of the country.”

Kitty was also involved in civic affairs. One avenue that especially caught my attention was in 1927, when a meeting of the Good Roads Club was publicized on the front page of the Journal. It talked of how “30 or more business men” had organized the group, which existed to help match improvements for roads throughout the county.

A list of those involved was included, and the only obviously female name was Kitty’s.

It may have been a coincidence, but I noticed that there was a subtle shift in McFarland’s ongoing advertisements in the paper. A few months after she took the top role, the aforementioned line about a lady always being available was replaced with assurances of “prompt service, day or night,” and a reminder about their ambulance availability.

Perhaps she wanted and needed the flexibility in her new life?

Beyond her professional and community work, Kitty also appeared to be extremely social. Numerous articles talk of her attendance at bridge parties. In 1924, she drove with friends to the dedication of Missouri’s new state Capitol building. Another report talks of her serving as hostess to around 30 couples at a dance at Shrine Hall. In 1926, while heading back from a business trip to Freeport, Ill., she stopped off in St. Louis for some additional business matters — and took in the World Series.

Things continued to crescendo into 1928, which Kitty undoubtedly planned to be a great year.

If only plans always worked out as we expect them to.

An article in the Journal that January told of Kitty’s success, noting that the undertaking company was the largest of its kind in south-central Missouri.

“The building … is now equipped with every modern facility, which enables this large establishment to give its patrons a real metropolitan service. This service maintains among other modern facilities including the largest type of motorized ambulance and hearse, and covers every feature of funeral directing in the most satisfactory manner.

“This establishment carries one of the largest and most complete stock of fine caskets in this part of the state. The stock is out of proportion to the needs and demands of a community the size of West Plains, but the business of this establishment extends over practically all of this part of the state.”

Positive momentum continued through the blossom of spring. Accounts talk about Kitty’s relationship with Bob Mullins, a local widower, war hero and produce dealer, and their intention to marry. Perhaps a desire to close a chapter and start another — and simply the growing business — led to the biggest announcement for the business to date in April 1928. That month, papers told of her new funeral home, for which she agreed to pay $7,500, and would be dedicated to the memory of her late husband and his parents:

“Mrs. Kitty McFarland of the McFarland Undertaking company, has recently purchased the beautiful brick residence of Mrs. W.N. Evans on West Main street one block from the square, and has announced that she will establish the McFarland Memorial Funeral Home, in memory of her late husband, Ray L. McFarland and his parents, the late Mr. and Mrs. J.H. McFarland.

“The Evans residence will be remodeled to make an ideal funeral home, the first floor being used for a funeral chapel. The basement will be used for storage and another building will be erected to take care of the stock, funeral cars and equipment. The second floor will be made into an apartment, which Mrs. McFarland will occupy.”

That West Plains news article was published on April 12, 1928.

Fire's cause was never confirmed

It was the very day before the blaze at the dance hall cost Kitty’s life, as well as those of Bob Mullins, her sweetheart, and 37 others.

“As quickly as the bodies of the dead were recovered they were removed to the two undertaking parlors here, the McFarland Undertaking Co., and the Ross-Davis Undertaking Co.,” noted the St. Louis Star the day after the disaster. “Twenty bodies were taken to the McFarland parlors, among them being that of the owner, Mrs. Kitty McFarland…”

Communication was clumsy at best at that time — perhaps in part because Billy Drago, manager of the local Western Union office, died in the explosion. Another example of the confusion and irony came through another mention in the Springfield Daily News, two days after the explosion:

“Mrs. Alma Lohmeyer, after reading the story of the disaster in The News, called West Plains to offer her assistance to Mrs. Kitty McFarland Undertaking Company,” noted the paper of Lohmeyer, a longtime funeral home operator. “She was informed that Mrs. McFarland had perished in the fire.”

Funerals for Kitty and Bob were held separately, but on the same day, in West Plains. Many other unidentifiable victims were laid to rest together, where today a monument marks their names.

Just 11 days after the disaster, the St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat shared the results of a coroner’s jury: Its six members concluded the deaths were caused by the fire and collapse the building — but failed to find a cause for the fire in the first place.

“It is generally felt here that no further action in the matter is likely to follow, and the investigation is closed,” the paper noted.

One of the best sources to learn about the disaster is “The West Plains Dance Hall Explosion,” a book written by Lin Waterhouse. In its pages, Waterhouse takes readers through many of the people affected by the horrific event, as well as theories of why what happened transpired.

Regardless of why it happened, the tragedy affected West Plains long after the smoke cleared from the fire.

“The blast snuffed out many from a generation of progressive leadership for West Plains and southwest Missouri,” writes Waterhouse. “The victims were educated and ambitious young citizens, the children of the community’s most prominent families. Almost to a person, they were future leaders — budding lawyers, educators and businesspeople.

“Fundamentalist religious voices denounced the lighthearted, spontaneous society of the 1920s, preaching that the sinful lovers of dance had been struck down by God. No one knows the number of individuals who changed their beliefs and lifestyles and warned their children about God’s wrath. Sadly, some mothers and fathers must have lived out their lives believing that their children burned in hell because they attended the April 13, 1928 dance at Bond Hall.”

Even though he was not alive at the time of the blast, one of the people affected in its aftermath is the aforementioned Jim McFarland, Kitty McFarland’s grandson. His father, Jack McFarland, was only 12 years old when his mother was killed, leaving him an orphan.

Given the size of the McFarland estate, the legal proceedings over who was to be Jack’s guardian were extensive, and remain relevant today.

“The case law in the state of Missouri for deciding guardianship of a minor is still based on that case from 1928 and my father,” says McFarland, who notes that it was decided that at age 13, a minor has the right to give input on who he or she would prefer as a guardian.

McFarland’s father spent years away from West Plains, first at a military academy, in college and in service during World War II. He ultimately spent most of his adult life in West Plains, and went to work at First National Bank, which transitioned through several iterations and eventually became Bank of America.

Through those years, memories of the past were ignored, but not far enough away to talk about.

Painful memories never discussed

“Dad rarely if ever talked about his childhood or his mother and father,” McFarland says, noting that the tragedy wasn’t discussed when he was growing up. “People just didn’t talk about such painful memories in those days.”

McFarland shares how he first learned of the blast that killed his grandmother: When he was around 8 years old, and home alone for the first time poking around drawers, when he discovered a newspaper article about it.

“When I came across that newspaper and first read it — I read it so fast and so intently,” he says. “Whenever they left the house for any reason, I went back to it. It really gave me an interest in local history. It really brings home the need to help young people discover their roots.”

McFarland gives an example of the previously mentioned fact that his sister was named in honor of his grandmother. “I don’t know that (my dad) realized his mother’s name was Mary Katherine, so he named her Kitty,” says McFarland.

Another link from the past to the present is through McFarland Undertaking Company, which in a sense has continued on.

“According to documents in my files, Kitty McFarland purchased the property for $7,500 on April 5, 1928 at which time she paid $2,500 down, and was to pay the balance of $5,000 by June 2, 1928 once ‘good and sufficient’ title was shown,” says McFarland, who says that his father’s guardian then petitioned the probate court to allow him to complete the purchase on behalf of his ward.

After several twists in the story, the McFarland business eventually became part of Robertson-Drago Funeral Home, which still exists today.

It’s now been 94 years since the night that shook West Plains, both literally and figuratively. The blast was so strong that it could be heard for miles, and caused such damage to the nearby courthouse that a new one had to be built. And it made such an impression that a 10-verse-long song was written about the disaster, which is accessible here.

It’s doubtful that anyone is alive today who remembers the blast firsthand. However, a link between past and present occurred in February 2022 when the building where the dance hall once stood also burned to the ground.

“To drive by it, it made you think a little bit of what it was like,” says McFarland of the building’s demise.

Despite the lingering question of why, McFarland notes that perhaps it’s OK not to know what happened to the building that housed the dance hall.

“Today, I think it’s one of the things you recognize you never really have an answer to,” he says. “You get to the point where it’s OK to be a mystery. You can accept that.”