The Springfield City Council’s exploration of revenue stability — the sources and reliance of the different sources of income for the city government — prompted a look at what Springfield does compared to cities of similar size and population in order to make money to provide services.

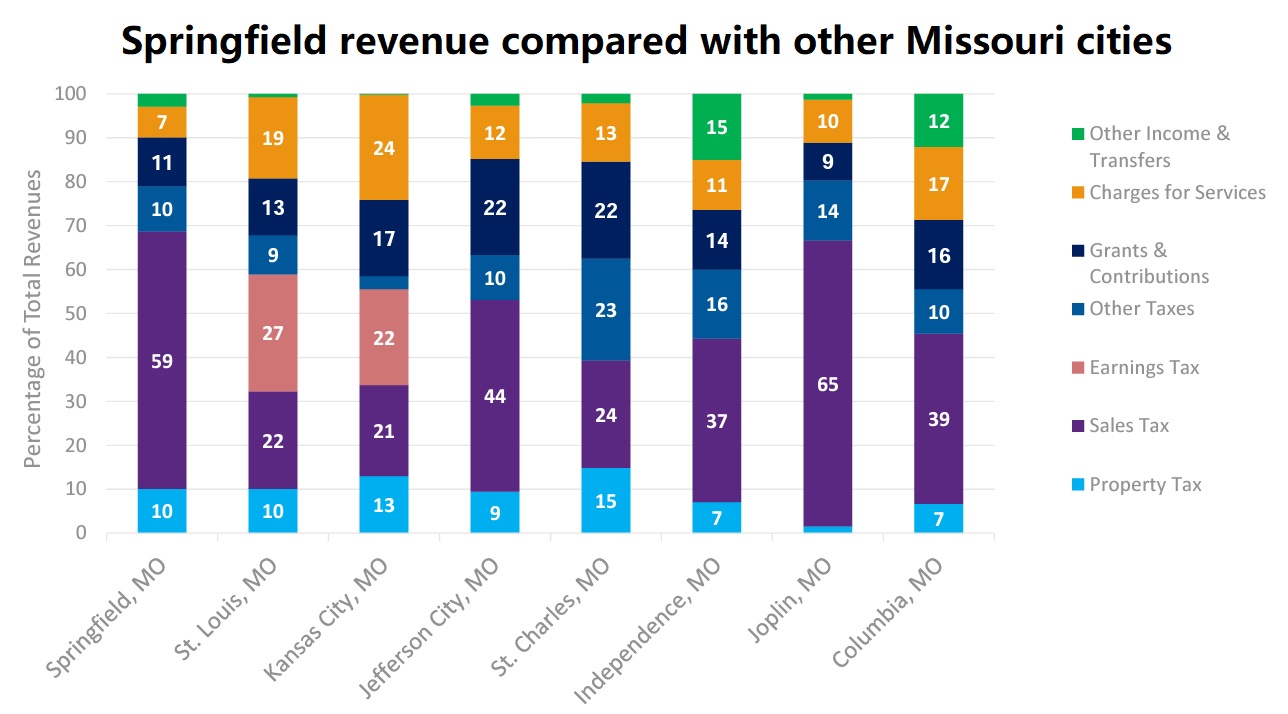

In 2020, Springfield got about 57 percent of its total revenue from sales taxes. That's a heavy reliance on a potentially volatile revenue source that bond rater Moody's notes in its independent assessment of Springfield's financial wellbeing and credibility.

In the 2023 fiscal year, which starts July 1, 2022, sales tax revenue is expected to make up about 60 percent of Springfield's overall income.

This makes Springfield similar to Huntsville, Alabama, which received 52 percent of its 2020 revenue from sales taxes. Hunstville, however, makes more money from property taxes and more money from charges for city services than Springfield does.

Why care?

Springfield's budget reflects what your tax dollars are up to, where they come from, what sorts of intent the people in leadership positions have and what sorts of services people can expect from their city.

Springfield Director of Finance David Holtmann provided some side-by-side revenue comparisons to the City Council as it goes through the task of setting a budget for the upcoming fiscal year, which begins July 1. The council expects to conduct a final vote on a budget bill at a meeting on June 13.

“The closest one to us would be Huntsville, Alabama, 52 percent of their governmental activity is provided by sales tax,” Holtmann said.

Similar cities like Waco, Texas; Savannah, Georgia; Chattanooga, Tennessee; and Abilene, Texas, have sales tax revenue percentages in the 20s.

In terms of revenue, Huntsville is similar to Springfield in many respects. “The Star of Alabama” is located in the northern end of the state and has a population of about 215,000 people, according to the 2020 U.S. Census. The census data shows that, like Springfield, much of Huntsville's workforce is made of suburbanites, as the metro area population is more than 490,000 people. Springfield has a population of about 170,000 people with a total metro area population of about 481,000.

Playing the percentages

General Councilman Craig Hosmer asked about Springfield’s reliance on sales tax. At least 59 percent of the $102 million budgeted for Springfield’s general revenue fund in the upcoming year is expected to come from sales tax. Hosmer wondered aloud if the City Council should take action to diversify the Queen City’s income sources.

“I know that 60 percent of the general revenue and 36 percent of the total revenue dependent on sales tax is obviously high, but is there a recommendation or is there a benchmark?” Hosmer asked.

No, Holtmann said.

“We’ve had the discussion about having many other revenue types, more stable revenue sources such as property tax,” Holtmann said. “Typically, you don’t see the volatility in property tax that you would normally see in sales tax, but as you know, our general fund does not have any property tax.”

Springfield does take in revenue for specialty property tax funds for public parks, public health, the Springfield Art Museum and for municipal debt service. The four property taxes add to 61.9 cents per $100 of assessed valuation.

“It seems like Moody’s keeps pointing out that that is a red flag for the city of Springfield,” Hosmer said.

The city of Springfield uses Moody’s as its independent investment and financial rating agency. Moody’s assigns ratings to government entities based on their ability to borrow money and repay it, assigning an overall rating for creditworthiness. The city of Springfield has an “Aa1” rating from Moody’s, the second-highest rating on the scale.

Different specialties

Huntsville Chamber of Commerce data from the spring of 2021 shows the major employers as the U.S. Army and Redstone Arsenal (38,000 people), the Huntsville Hospital (9,352), NASA (6,000), Huntsville City Schools (3,000) and the Boeing Company (2,900). Huntsville is a major jet propulsion research site for the U.S. Army and for NASA.

In Springfield, the major employers are CoxHealth, (12,164 employees), Mercy (8,202), Walmart (5,381), Springfield Public Schools (3,694) and Bass Pro Shops and White River Marine Group (3,127), according to data from the Springfield Chamber of Commerce for the spring of 2021.

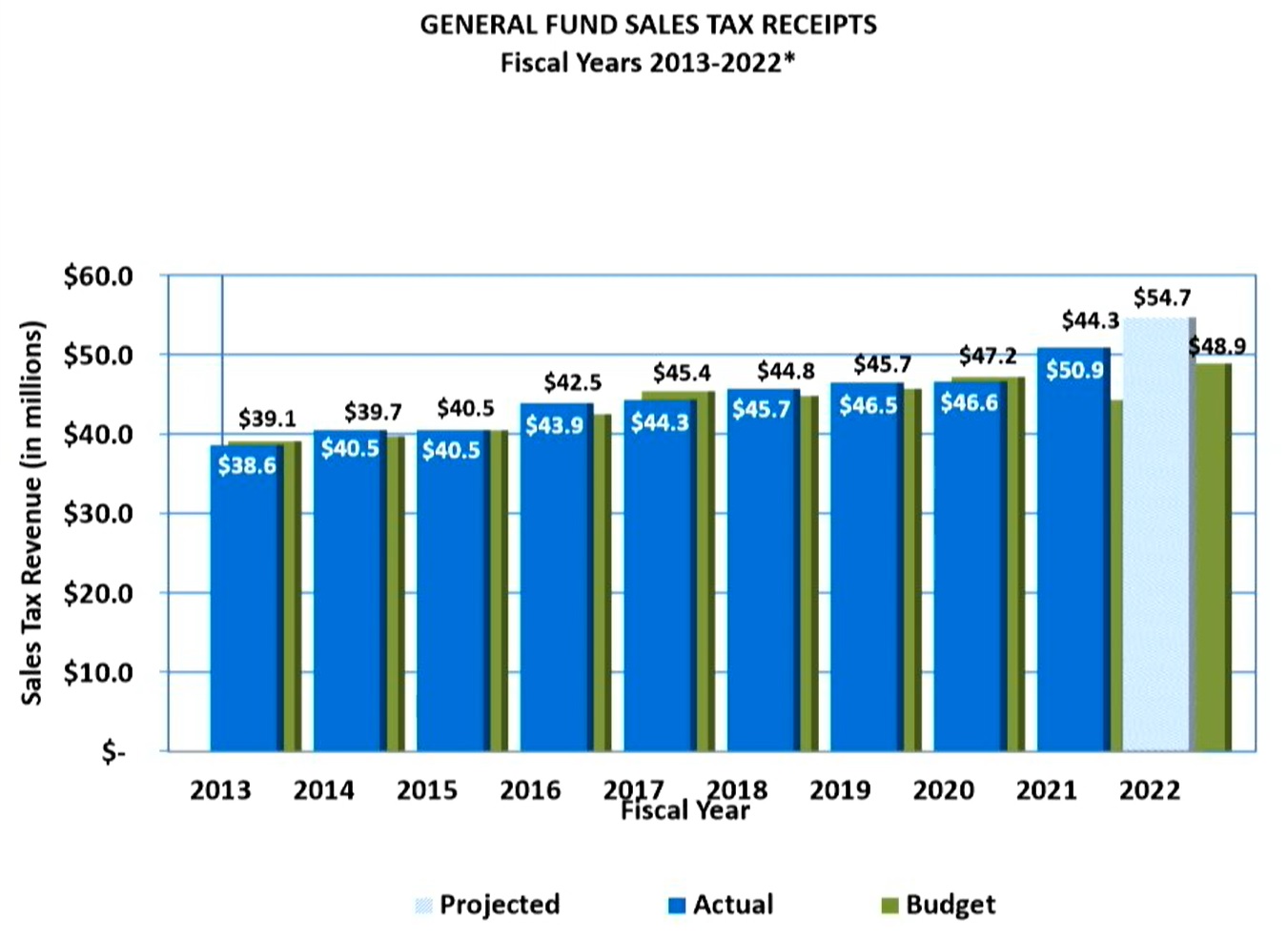

“When we come to some economic downside such as we’re getting with inflation and so forth, there can be some concern that sales tax will start to slow down, and we’ve seen in the past where it has declined,” Holtmann said.

Money comes into Springfield’s city government from a range of sources, but Moody’s notes Springfield’s “reliance on economically sensitive sales tax revenue” as a cautionary point.

Mayor Ken McClure looked at other revenue sources on the chart and noted how other cities make more money from the services they provide to residents and businesses.

“It’s interesting just eyeballing this, Columbia, South Carolina, a huge element is charges for services, it looks like, and we’re fairly low on that,” McClure said.

The mayor noted that Springfield examines fees and fee adjustments through the City Council Committee on Finance and Administration.

Springfield vs. the rest of Missouri

Kansas City and St. Louis both have earnings taxes, which are absent in other Missouri cities.

“Both entities have some significant resources allocated into charges for services. In Kansas City, that represents about $316 million of their $1.3 billion governmental activities revenue. In that, the biggest bulk of that was $112 million in utility taxes,” Holtmann said.

Unlike Springfield, which runs its own utilities, Kansas City is served by Evergy, the publicly traded company created when Westar merged with Kansas City Power and Light in 2016.

“Kansas City is served by an investor-owned utility,” McClure said.

The utility comparison is but one of the many reasons why it’s hard for Springfield to achieve a true apples-to-apples comparison when it comes to looking at revenue models. Holtmann gave an example of St. Louis, where the city controls trash collection and towing of abandoned vehicles, and has about $28 million in annual revenue to show for it.

Payments in lieu of taxes (PILOT or PILT), as defined by the U.S. Department of the Interior, are “federal payments to local governments to help offset losses in property taxes due to the existence of nontaxable federal lands within their boundaries.” Payments in lieu of taxes may also be imposed on municipally-owned utilities, of which Springfield City Utilities is one. Springfield also takes in money from licenses and fines, gross receipt taxes on sales by corporations, cable revenue and cigarette tax, among other sources.

When looking at how Springfield compares to Joplin, Columbia, St. Joseph and other major cities in Missouri, Holtmann said a true side-by-side comparison is tough to get.

“For Columbia, $14 million or 10 percent of their other income was from their PILOT activity. Same for Independence, about $19 million is from their PILOT activity. In the city of Springfield, ours is reflected in our other taxes, so it’s not complete apples-to-apples on the governmental activities allocation, but that’s just how they’ve been presented year after year,” Holtmann said.

City Utilities provides services in-kind for all of Springfield’s municipal government buildings, which Holtmann said adds up to about $13 million worth of complimentary services per year.

Zone 4 Councilman Matthew Simpson notes that most Missouri cities control water and sewer utilities, but Columbia and Springfield run their own electric utilities. In a list of 12 major municipalities, Springfield was the only one that controlled its own natural gas utility.

“Looking at this, Springfield is the only one that’s municipally owned for all four of the utilities our of this group,” Simpson said. “Is Springfield also the only one where the utility operates the public transportation system for the city?”

“It is the only one in the nation,” McClure said.

“That seems like something we need to take into consideration,” Simpson said.

“(The City Utilities bus system) is another amount that is subsidized by City Utilities,” Holtmann said. “That function does not break even. That is a cost that all of the utility users of CU are helping to contribute to.”

The Springfield City Council is scheduled to have the preliminary reading and introduction of its 2023 budget bill on May 31.