In March, I wrote about a con man from Republic who was described by federal prosecutors as a “serial fraudster.”

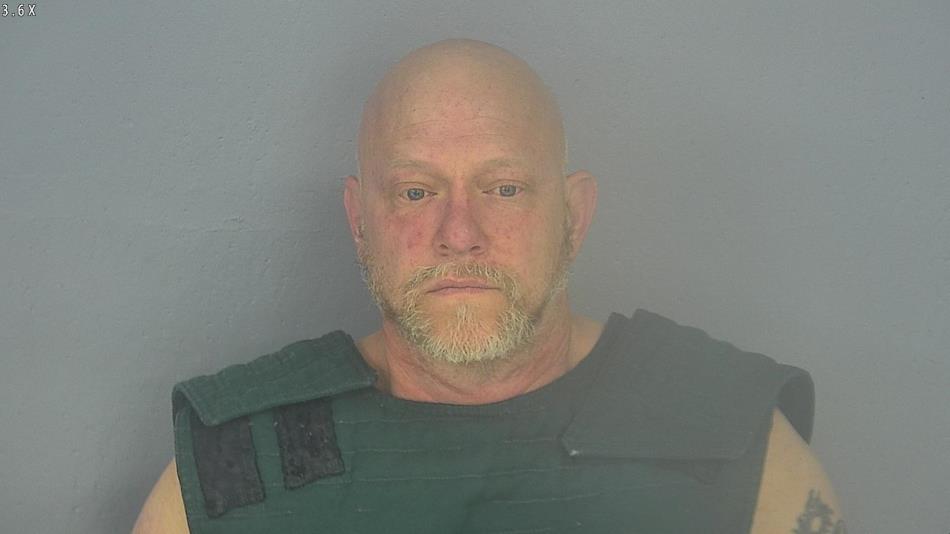

George Finley Myers, Jr., 48, former owner of Beefcakes restaurant in Republic, was sentenced to 4 years and 8 months in prison.

In court documents, prosecutors stated that the restaurant, which has since closed, was probably one of Myers’ few business ventures that was not a criminal enterprise.

In my story on Myers, I didn't mention a part of his plea agreement that struck me as not only odd but unfair to him and to anyone else negotiating a guilty plea with the U.S. Attorney's Office here in the Ozarks.

Myers was asked to waive his rights to seek any more records involved in the investigation or prosecution of his case.

“The defendant waives all of his rights, whether asserted directly or by a representative, to request or receive from any department or agency of the United States any records pertaining to the investigation or prosecution of this case including, without limitation, any records that may be sought under the Freedom of Information Act.”

It seems the phrase “or by a representative” would include any lawyer who in the future might be representing Myers in this case

Myers did, in fact, agree to waive this right.

Why is this waiver scary?

This waiver sounds scary to me in large part because in 2017, while at the News-Leader, I wrote a series of stories on what turned out to be the wrongful conviction of a Buffalo man by the name of Brad Jennings.

Jennings was convicted at trial in 2009 because, in my view, his defense lawyer was ill-prepared and did a shockingly poor job.

On the other hand, he was set free after more than 8 years in prison only because his two St. Louis lawyers — Bob Ramsey and his daughter Elizabeth — did amazing and relentless work.

It is nearly impossible to free a defendant who has had his day in court and been convicted. It seems to me it would be completely impossible to do so if a defense team could not ask for further records that might play a significant role in proving prosecutorial or police misconduct.

Would this waiver prevent that from happening in federal court?

Jennings, in state court, was freed from prison because the lead investigator, a sergeant with the Missouri State Highway Patrol, never revealed a key piece of evidence that would have helped Jennings' defense.

The evidence was a negative gun-shot residue test that indicated it was unlikely that Jennings fired a gun the night his wife died from a shot to the head.

Dallas County officials had initially ruled the case a suicide.

The Missouri State Highway Patrol investigator said he didn't reveal the gun-shot residue test because he didn't know about it — despite the fact he also acknowledged in court proceedings that he received lab reports on other tests in the case on the very same day the gun-shot residue test result was faxed to him at the same number.

The case against Myers, the “serial fraudster,” was federal, not state.

Why would the federal government want to bar a defendant or a defense attorney from seeking further records even after a defendant pleads guilty?

“FOIA waiver saves time and resources”

I asked that question of Don Ledford, spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney's Office of the Western District of Missouri.

He replied via email.

“The FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) waiver is a standard clause in our plea agreements. Most often, FOIA requests are made by defendants who are pursuing an appeal of their sentence and trying to gather information for that purpose.

“After a defendant pleads guilty, however, there isn’t really a legitimate need for them to file a FOIA request. It makes sense that, just as they waive their right to appeal, they would likewise waive their FOIA rights.

“One of the reasons our office enters into plea agreements with defendants is because of the savings in time and resources that a guilty plea represents compared to a trial, both for our office and for the court.

“In the same way, the FOIA waiver saves time and resources, which is one of the benefits to our office of entering into a plea agreement.”

I asked veteran criminal defense attorney Thomas Carver, of Springfield, who works in federal and state courts, about the FOIA waiver.

Carver is a former president of the Missouri Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers.

“My only thought is that it might cut down on prisoner litigation,” Carver said via email.

“There is a certain percentage of inmates whose hobby is to litigate. Mostly, it involves inmates who have exhausted their avenue for post-conviction relief and the only way they can get back into court is by showing that the government withheld evidence in their criminal case and that the evidence would have changed the outcome of the case had the defendant or his lawyer known about it.

“I believe the hope is that if they make a FOIA request they might turn up something that would help them to get back into court.

“I'm unsure if that provision is enforceable, especially in the context of prosecutorial misconduct or ineffective assistance of counsel.”

In other words, if I may, the federal government seeks the waiver because it wants to limit frivolous litigation initiated by prisoners who have pleaded guilty. The limitation saves time and money.

At the same time, this waiver can add a legal hurdle to those who might have been wrongfully convicted, people already facing the herculean task of proving it.

This is Pokin Around column No. 40.