People experiencing homelessness can now face criminal charges for sleeping or camping on public property without authorization.

That's due to House Bill 1606, which was newly signed into law on June 29 by Gov. Mike Parson. This will become effective on January 1, 2023.

“No person shall be permitted to use state-owned lands for unauthorized sleeping, camping or long-term shelters,” the provision reads. “Any violation shall be a Class C misdemeanor; however the first offense shall be a warning with no citation.”

The bill directs state and federal funds towards facilities and designated properties for persons experiencing homelessness, in addition to redirecting funding from permanent housing projects towards short-term housing, mental health resources and substance misuse treatment.

The amendment in HB 1606 (Section 67.2300), sponsored by Rep. Bruce DeGroot (R-District 101), was based on a Senate bill by Sen. Holly Rehder (R-District 27) and model legislation by Austin, Texas think tank The Cicero Institute.

“According to research conducted by UCLA, three-quarters of long-term homeless individuals struggle with mental health issues or substance misuse disorders. The national model of ‘housing first’ has failed to focus on these root causes,” Rehder said. “This legislation shifts our focus from long-term housing to short-term housing coupled with wrap-around mental health services.”

Housing first is an approach to tackling homelessness by emphasizing the need for individuals to be housing before they’re able to deal with other issues in their life such as sobriety, employment and relationships.

Eden Village, a tiny home community with locations in two Springfield neighborhoods and plans underway for expansion in a number of U.S. cities, are built on the housing-first model that the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has deemed “successful.” Contrary to Rehder’s comments, housing-first models often employ permanent supportive housing that provide supportive services that often lead to “improvements in quality of life, in the areas of health, mental health, substance use, and employment, as a result of achieving housing.”

“It’s an absolute insult that Missouri state senators and representatives would denounce housing-first without visiting Eden Village,” Nate Schlueter, Eden Village’s chief visionary officer, said. “We’re appalled that they would be that bold to not come and tour America’s model that started in Missouri.”

Arizona, Georgia and Wisconsin are just a few other states that have proposed or enacted similar legislation, all with The Cicero Institute’s direct influence.

“Enacting this bill puts Missouri squarely on track to decrease street homelessness in a cost-effective, compassionate manner,” Rep. DeGroot said. “Other states have already taken notice and it may very well become the conservative model used throughout the nation to help those in need.”

However, that same optimism is not shared by some homeless advocacy groups. A letter to the HUD from the National Coalition for Housing Justice (NCHJ) expressed concern over the ramifications of the bill.

“Given our country’s historical racialization of criminalization and institutionalization, these policies will have deep disparate impacts on Black, Indigenous, and people of color, persons with disabilities and LBGTQ+ persons,” the letter reads.

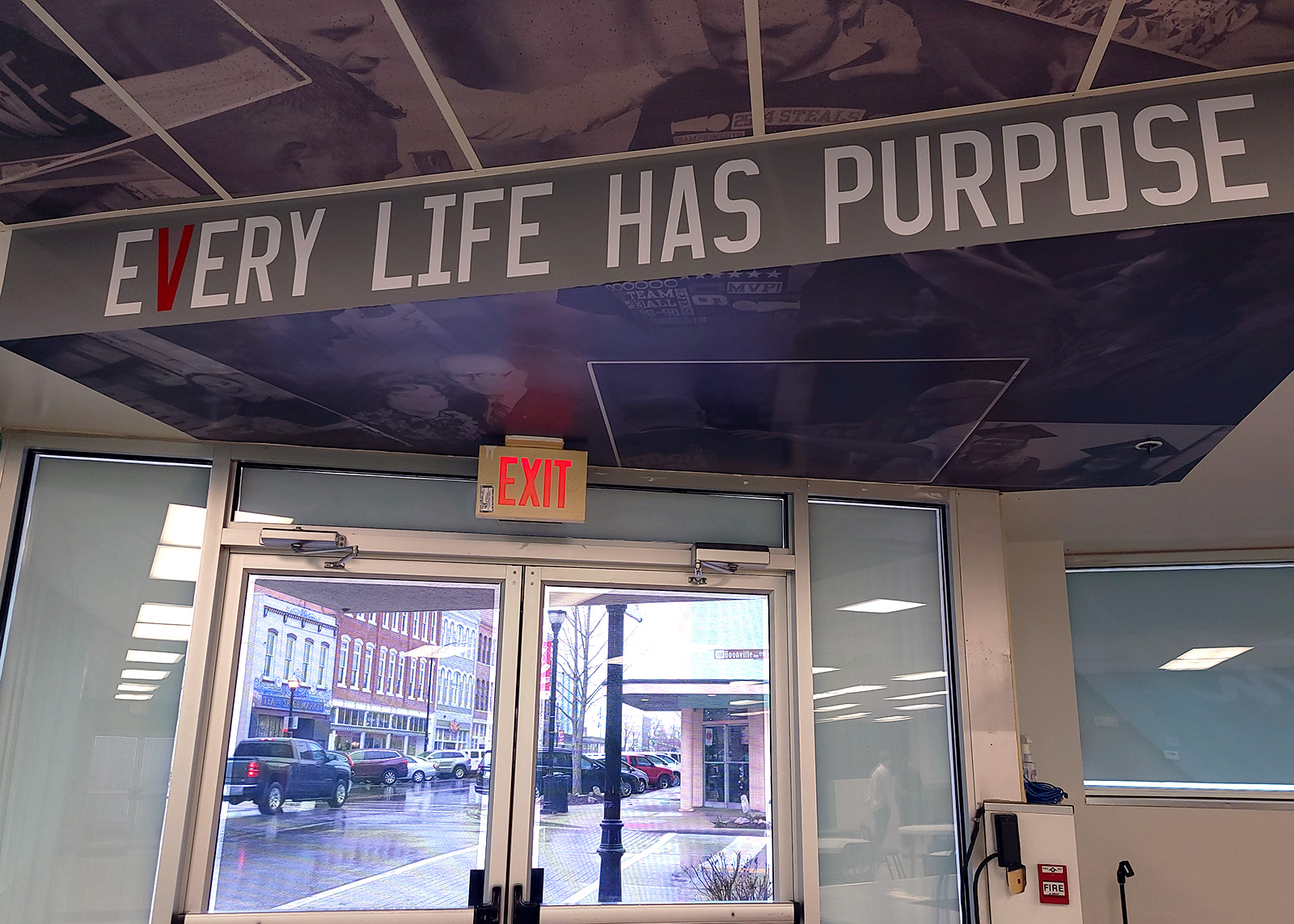

Story continues below:

MORE ON HOMELESSNESS

Additionally, the NCHJ believes that this amendment in HB 1606 may put the state in direct conflict with federal law and could result in the HUD withholding funding.

“The vague inclusion of ‘federal funds for housing or homelessness’ could arguably impact multiple funding streams,” the letter details. “Including, but not limited to, Projects for Assistance in Transition from Homelessness, Emergency Solutions Grants, Community Development Block Grant, and Community Services Block Grants — not to mention HUD’s new Unsheltered Homelessness Grant — interfering with Congressional and agency intent for the use of these funds. Allowing states to subvert the purposes of federal funds would set a concerning precedent across federal programs.”

The text of the bill details that political subdivisions, primarily municipalities, must maintain a per-capita homelessness rate at or below the state average or enforce ordinances that comply with the law, or could face a loss in state funding or civil action by the Attorney General.

“It is highly likely that one year after this law is initiated communities such as St. Louis, Kansas City, Springfield, Jefferson City, Columbia and even Branson will be under threat to lose their state funding for housing/homelessness because they will not be able to show any progress on reducing the numbers of homeless people,” a statement from the National Coalition for the Homeless reads.

Because of the unreliability of state and county funding, Eden Village, a 501(c)(3), has moved to complete private support, according to Schlueter.

Other local organizations are also worried about the impact the new law will have on the area’s homeless population. Christie Love, pastor of The Connecting Grounds church, which is known for their homeless outreach programs, conveyed her apprehension to the new law.

“Today is a dark day for individuals without stable shelter throughout the state of Missouri,” Love said in a Facebook post, “... please understand that this action criminalizes homelessness on a state level, subjecting people to additional barriers to employment, shelter, and stability.”

Love encourages individuals experiencing homelessness to join the Springfield Without Shelter online community, where they can ask questions and stay updated on the impact the legislation may have on them.

“The only way that we’re going to end homelessness and have cities where no one sleeps outside is if the community jumps on the bandwagon and is tired of looking at it,” Schlueter said. “The flip side of this bill is everybody’s going to be looking at it because their number one recommendation is a parking lot.”

Jack McGee is a general assignment reporter at the Hauxeda, with a focus on regional politics. McGee most recently worked at Carbon Trace Productions, a documentary film company, as a producer. He’s a Missouri State University graduate and former reporter at student-led newspaper The Standard. More by Jack McGee