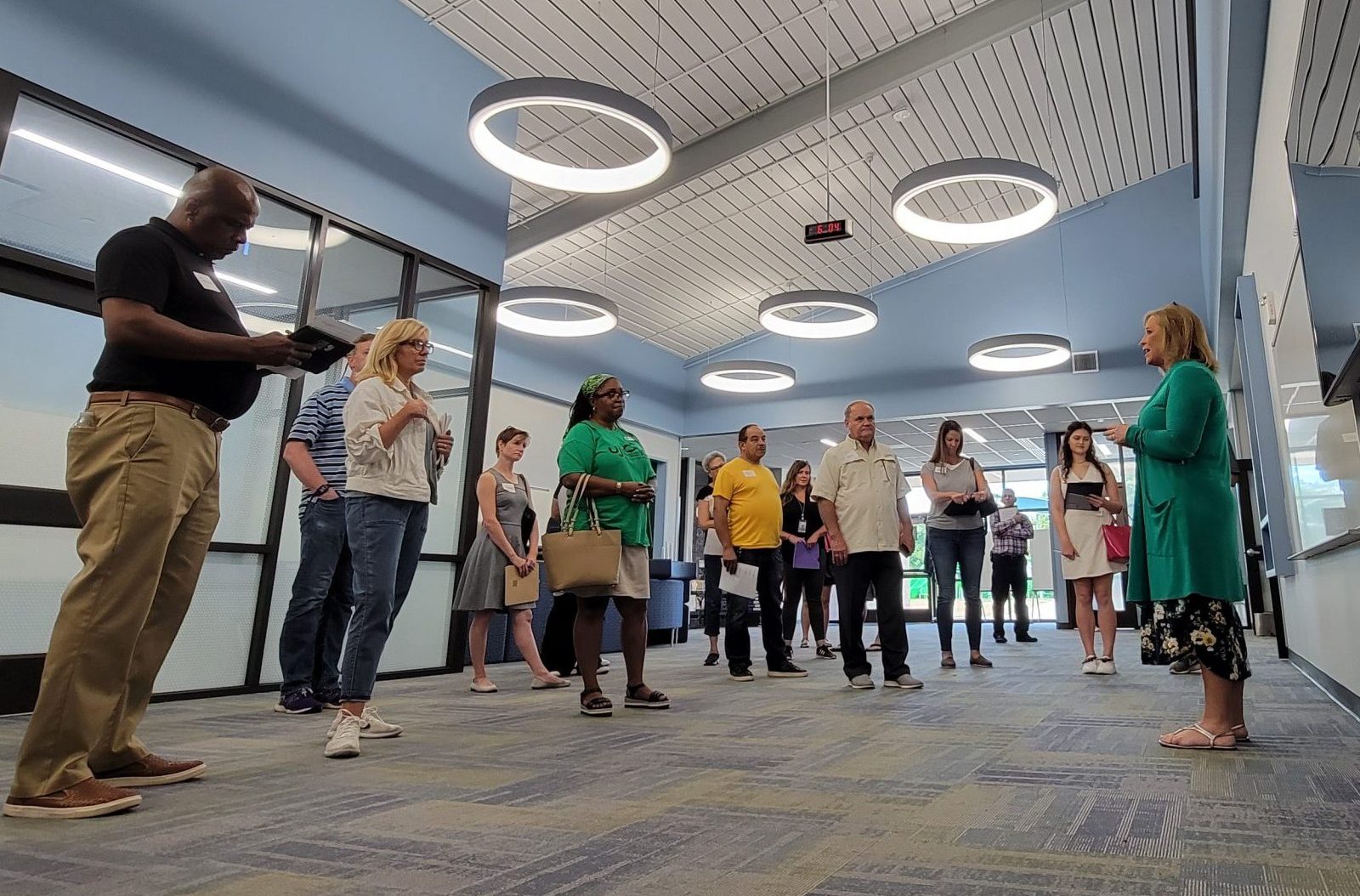

Answer Man: Now that the Springfield Public Schools Community Task Force on Facilities has formed and is looking at individual schools to assess needs, I have three questions regarding Pipkin Middle School.

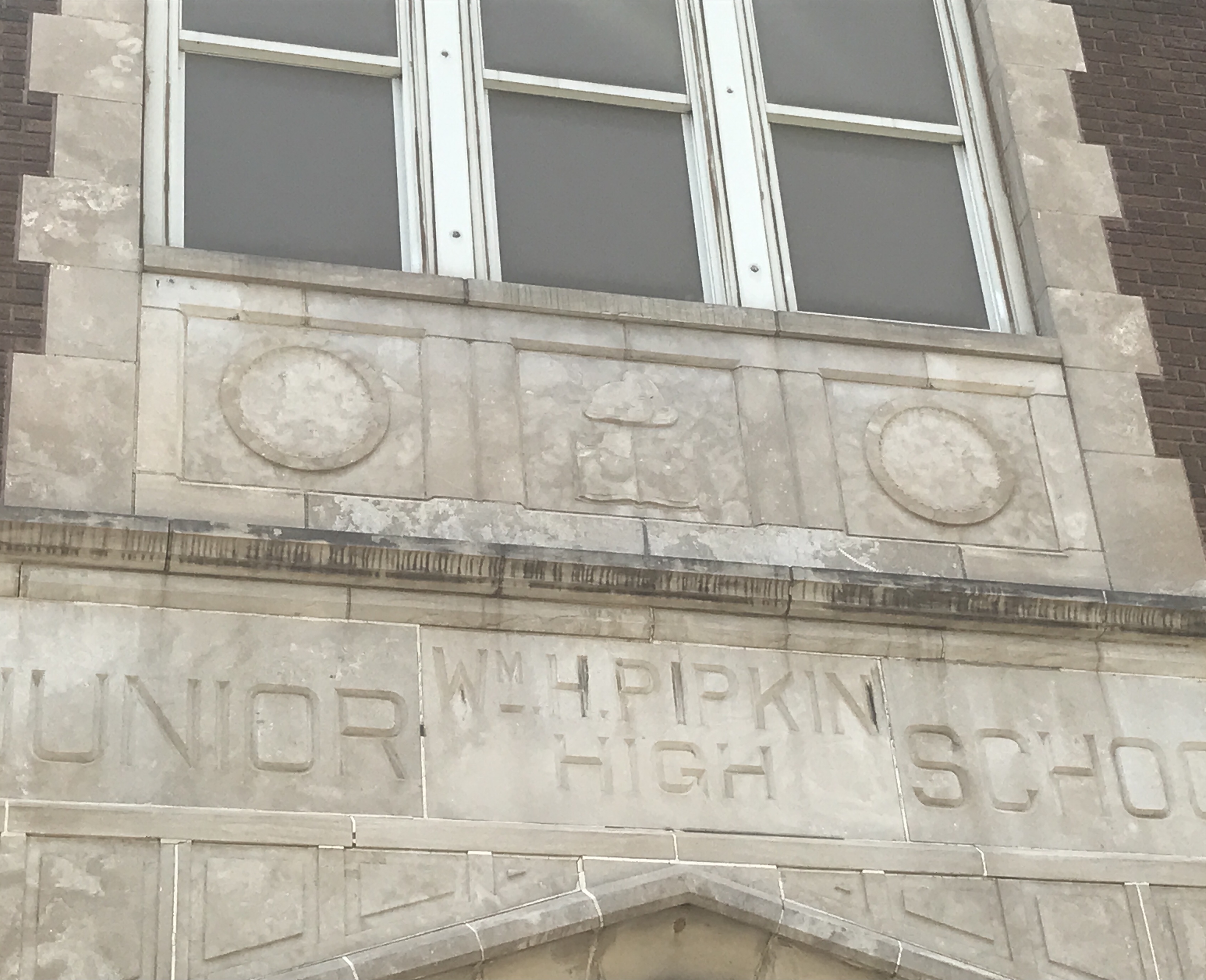

- If you look above the main entrance to Pipkin you'll see two circles cut into the stone, with nothing in the circles. I've been told that a hammer once was in one circle and a sickle was once in the other. Over time, the hammer and sickle (together) became more closely associated with communism. As a result, I've heard, the school district sandblasted them off the building. Is this true?

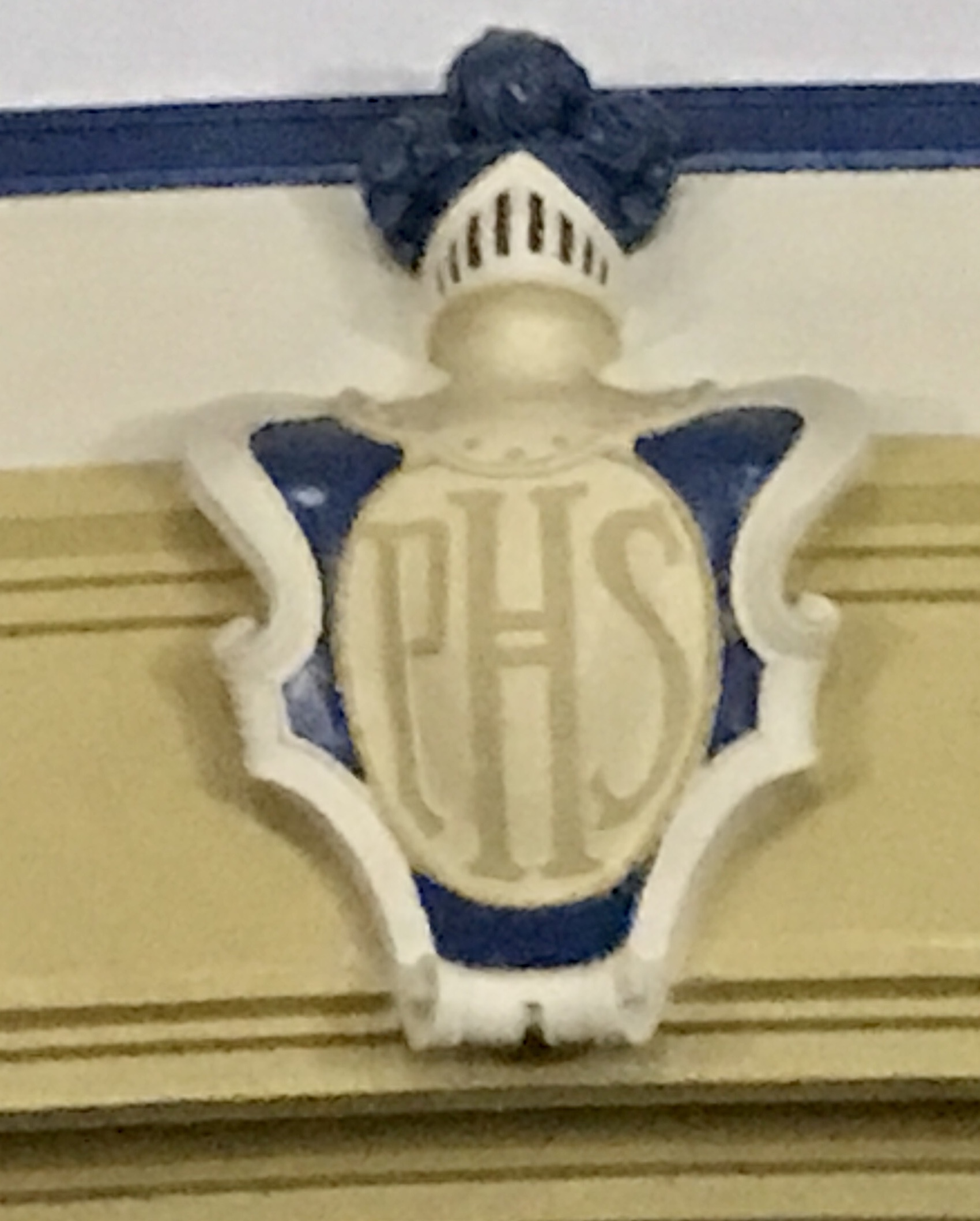

- Second, above the stage in the Pipkin auditorium is a shield-shaped emblem with the letters PHS. Why is it “PHS” since Pipkin was never a high school? What does “PHS” stand for?

- Finally, on the hallway of the main floor, why are there so many cracks in the concrete? I have a theory on this one.

— Steve Ingalsbe, of Springfield

To be honest, Steve, I feel pressure because in my research I've learned that you taught math for 19 years at Pipkin and, in fact, in 2006 you were the district's teacher of the year.

You also taught football at Pipkin and, on top of all that, you went to school at Pipkin.

Nevertheless, I did my due diligence and here's what I've learned about the school at 1215 N. Boonville Ave., which opened in 1925.

In 1934, Texas evangelist Mel Morris came to Springfield, our Queen City, and was aghast by what he saw — a hammer in one of the ovals and a sickle in the other. (In the middle, between them, you can still vaguely see a lamp over the book of knowledge, possibly a Bible.)

Morris raised a ruckus about the hammer and the sickle and their symbolic ties to communism.

By the time Mr. Morris packed up and left, he assumed something would be done to remove them.

Was he in for a surprise when he came back two years later. They were still there, over Pipkin's front door.

According to a story in the Springfield Leader and Press:

“He renewed his protests in his nightly sermons at the Gospel Tabernacle, he stirred his hearers to such indignation that they were almost of a mind ‘to take ladders and chairs and tear it down.'

“But he restrained them, he said, because he prefers ‘orderly, organized protest.'”

To top it off, Morris said that if he had a son, he would not even let the boy enter Pipkin.

(There is no record I could find indicating what he would have done if he had a daughter.)

Harry P. Study, then school superintendent, was a “bit irritated” by Morris' renewed protest, the paper reported.

He said this: “I heard all about this two years ago. On the right and left are the hammer and sickle of industry and labor; in the center the open book and lamp of knowledge and light. The book is possibly the Bible.”

The protest was taken up by the local American Legion post, and in March 1940 the hammer and the sickle were removed.

Study told the paper then that the school's carving wasn't a true replica of the communist emblem anyway. The sickle and hammer were separated by a torch. He said he was sure that when the figures were cut in the stone, there was no intended link to communism or to Russia. (The hammer and sickle together — and a star —were on the flag of the Soviet Union from 1955 to 1991.)

I find it interesting that by 1940 the superintendent was no longer describing the book in the middle — which is still visible — as possibly being a Bible.

COLUMN CONTINUES BELOW:

Why PHS?

Let's move on to question two: Why the letters “PHS”?

Stephen Hall, spokesman for the school district, tells me that, indeed, Pipkin was never a high school.

His best guess is that “PHS” stands for Pipkin Honor Society.

Ingalsbe points out that the letter “H” in the “PHS” has a double horizontal bar. Perhaps, he says, that the “J” for “Junior” is part of the letter H.

For the record, Pipkin was named for school board member William H. Pipkin.

I have a theory of my own regarding “PHS.”

First off, I'm confident it does not stand for “Pipkin Hammer Sickle.”

But I did find a short item in the local newspaper dated March 16, 1926, that stated the Pipkin music club would be presenting a show at “Pipkin High.”

It did not say “Pipkin Junior High.” It said “Pipkin High.”

Similarly, I found an ad in the paper dated Aug. 27, 1925, from a girl looking for work after school. She said she lived near “Pipkin High.”

Remember, 1925 was a time when a smaller percentage of eighth-grade graduates went on to high school.

In my view, there's a good chance the district's three brand new junior high schools were referred to simply as high schools.

At the time, the district had but one four-year high school.

Why the cracks?

On to the third question: Why so many cracks in the concrete floor on the main level of Pipkin?

I met Principal Duane Cox at Pipkin Friday. Unfortunately, he's been there only three years.

Here's my best theory on the cracks. And it comes from — of all people — Steve Ingalsbe, the man who asked me these questions.

I made my Answer Man debut in June 2014 in the Springfield News-Leader. This marks a first for me in that my source for the answer is the same person who asked me the question.

(I suspect that when Ingalsbe told me he had a theory on the cracks, this was it.)

Ingalsbe wrote a column for the News-Leader on June 30, 1999.

He stated that back in the 1920s, the school presented an $8 million bond issue to replace condemned elementary schools and to build its first three junior highs: Jarrett, Reed and Pipkin.

Voters turned it down.

But a $600,000 bond issue passed later. The money would be used to complete the three junior highs.

Jarrett and Reed were completed and they opened in 1923. But the district ran out of money before Pipkin could be finished.

Ingalsbe wrote: “Pipkin stood as an embarrassing skeleton of concrete floors and unfinished walls. Two years of exposure to the elements resulted in the patchwork quilt of hallways.”

Study (mentioned earlier) was hired as superintendent in 1924, and his priority No. 1 was finishing Pipkin.

Fun Fact: The general contractor for finishing Pipkin was M.E. Gillioz of Monett, who also built the historic Gillioz Theatre, which opened Oct. 11, 1926.

This is Answer Man Column No. 18.