Four months after the Hauxeda partnered with KY3 to publish a series about the challenges facing parents — and the child care industry in the Ozarks — things are changing.

Some developments have led to more spots becoming available now and potentially in the future. These include:

- Several major employers are now interested in creating child care options for current and future employees.

- Child Care Connect, a newly created resource to connect parents with child care providers who have open spots, has helped about 100 local families so far.

- The new Childhood Provider Network — which brings together child care providers and professionals to better communicate the issues and needs to state agencies and lawmakers — held its first meeting this past week in Springfield. The seven regions of the state will also have Childhood Provider Network meetings and groups, as part of a statewide movement initiated by Kids Win Missouri.

- At least one current provider was able to raise wages and re-open classrooms.

While not all of those developments stem directly from the Child Care Crisis series, Dana Carroll with Community Partnership of the Ozarks said the week-long series of stories helped shine a light on problems within the industry and got lawmakers and business leaders interested in finding solutions.

Carroll is CPO’s vice president of Early Childhood and Family Development.

“People are having conversations they weren’t having,” Carroll said. “We’ve had several businesses just take an interest. Many have reached out and said, ‘I don’t really know what I want to do, but I want to do something.’”

Why care?

- In a few short months at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of spots for children at licensed day cares in Greene County dipped by one-third, a loss of nearly 3,600 slots. While many programs have since reopened, we are still down about 700 slots from pre-pandemic numbers.

- Estimates show the demand for child care is even greater, with parents of nearly 4,200 children under age 6 turning to unlicensed in-home care, grandparents, family or friends to help fill the need.

- The typical waitlist for child care at a licensed center in Springfield is anywhere from 9 to 18 months — even longer for babies under age 2.

- The average pay for child care is barely above $20,000. About 100,000 child care employees across the nation have left the profession in recent years. Most child care centers in Greene County continue to operate at one-half to two-thirds of capacity due to staff shortages.

- Despite low pay and long hours for child care workers, affordable child care remains out of reach for many parents in low- and moderate-income households. Based on tuition rates charged in Greene County, a family of four with two children will spend about $22,000 each year on child care — and the median household income in the county is roughly $47,000. The federal government advises day care costs should be no more than 7 percent of a household budget.

Childhood Provider Network meetings kick off in Springfield

At the first Childhood Provider Network meeting held Nov. 29 at Community Partnership of the Ozarks, Karrie Ridder with CoxHealth’s child care program said the time is right for child care professionals to talk to legislators. Ridder has served on an advisory group with Kids Win Missouri for a while now and spent time in Jefferson City a few months ago sharing with lawmakers about the challenges providers are facing.

“They were listening,” she said. “We have the legislators’ ears right now with child care. This is a great time for us to be advocating to them about what we need.”

Ridder said she shared with lawmakers how difficult it is for her to hire staff, despite the fact that Cox has a recruitment department that helps with this.

“We at Cox are really struggling right now,” she said. “We can’t enroll any children. We have space to enroll children, but we don’t have the workforce to do it.”

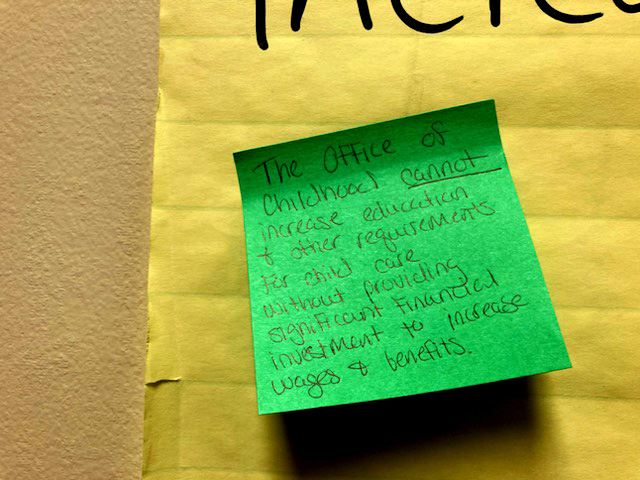

At that same meeting, Carroll asked attendees — a mix of in-home child care providers, child care center directors, home visitors and other child care professionals — to give feedback on different topics, including improved training and the state’s subsidy program.

Those topics were chosen by Missouri’s new Office of Childhood, a state agency launched in 2021 that consolidates early childhood programs from the departments of social services, health and senior services and education into one office.

Several employers looking for solutions

Prior to the meeting Tuesday, Carroll spoke to the Daily Citizen about other developments in the child care industry.

One really exciting change that’s happened since the Daily Citizen’s and KY3’s child care crisis project, Carroll said, is that the local business community has really taken an interest in the issue with the hopes of being able to attract and retain future employees.

The Partnership Industrial Centers on the east and west sides of Springfield, for example, are surveying their businesses to determine if there’s enough interest to open new child care centers to serve their employees or to create a pod-model child care center, or if it would be best to partner with existing child care centers to reserve spots, Carroll said.

Carroll said business leaders from major employers like SRC Holdings Corporation and CNH Industrial have joined the Child Care Collaborative’s Workforce Development Committee, which meets monthly to discuss potential solutions. The committee is not new, Carroll said, but its focus recently shifted to figuring out child care solutions for employees.

Child Care Connect program has helped about 100 families so far

In large part as a result of the series, Community Partnership of the Ozarks partnered with Springfield Public Schools to create Child Care Connect, an online resource to match parents who are seeking child care with providers in this community that have open spots.

Child Care Connect can be found on Community Partnership of the Ozarks’ website and serves Greene, Christian, Polk and Webster counties. Child care providers are asked to continually update their information about available spots via a JotForm.

Parents, too, can fill out a JotForm that details what type of child care they are looking for, how many children and the ages.

According to Carroll, at least 97 families have been successfully connected with appropriate child care through the Child Care Connect program.

CPO hasn’t done any kind of marketing for the Child Care Connect program, but Carroll said people are learning about it from the child care crisis series and word-of-mouth.

At least one provider able to raise wages

By all accounts, the biggest challenge for the child care industry is the low salaries for its workers. Because the state has strict rules about teacher-to-child ratios, there’s really no way child care providers could pass the true cost of care on to parents. Since the pay is not competitive and the work is not easy, child care providers wind up with empty classrooms due to staffing shortages.

At least one nonprofit child care provider has been able to raise wages for its workers in recent months and attract employees.

The Developmental Center of the Ozarks had several classrooms in its child care program that were closed due to staffing. The board of directors approved increasing salaries $2-$3 an hour in October, said Marisa DeClue, executive director of the Developmental Center of the Ozarks.

This immediately attracted applicants and allowed the DCO to re-open classrooms and take families off the waiting list.

The DCO’s child care program offers a daily classroom setting for infants and children 6 weeks through 6 years who require specialized programs and therapies as well as children who do not.

But because many do require specialized programs and therapies, DeClue said it’s important to keep teacher-to-child ratios low so babies and children get the care and attention they need.

She estimates the average true cost of care (varies by age) for DCO babies and children is about $310 a week. According to the website, DCO charges families $230 a week for babies to age 2, $170 for ages 2-3 and $160 for ages 3-6.

DeClue explained that the financial losses in the child care program are partially absorbed by the many other services and programs offered by the DCO. The DCO offers a technology and learning center for people 16 and older with developmental disabilities, therapy services, an adult day center, employment services and a community-based learning program.

And just because the board of directors approved raising wages doesn’t mean the nonprofit can do so without community support, DeClue said.

“As we’re looking at our 2023 budget, the child care program is running at a deficit. There’s absolutely no way that we can pass all those expenses on to families,” she said. “Our board is dedicated to serving children, especially those that are most vulnerable. But we also have a responsibility, and so that’s really where the community for us steps in. We are a 501c3 nonprofit organization. That has definitely made a difference in our ability to operate as we do.”

Those in field say state-run programs need to be fixed

Despite these positive developments, Carroll said there’s much that needs improving, including some state-run programs.

Chief among them, according to Carroll, is the Department of Social Services’ Family Care Safety Registry. This registry conducts screenings for the purpose of employing caregivers in child care, long term care, mental health care, or personal care settings.

However, it is taking too long for new hires to be screened. And since staffing classrooms has always been one of the biggest challenges child care providers face, speeding up the screening process is a must, Carroll said.

“They are slow to get approved because the system has been flooded,” she said. “If I can’t get that done on a worker, then I can’t get them into a classroom. It just slows down the process, and we need to get people in and working quickly.”

Another state-run program that needs to be fixed is the subsidy program for foster children, Carroll said. The state pays a subsidy amount for children in foster care to child care providers, and the amount hasn’t been raised in years. However, the cost of care has increased.

Child care providers are not allowed to ask foster parents to pay the difference, according to the law.

“So the provider has to eat those costs. That can’t be. That can’t continue to happen,” Carroll said. “Up until now, the state has not chosen to fix that issue.”

Carroll said a lot of child care providers will accept two or four foster children and absorb the costs, but they can’t take more than that and still keep the doors open.

These are just a few of the issues the Childhood Provider Network will be communicating to lawmakers and state officials about, Carroll said.