Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct an ID of a member in a photograph of the County Line band, and to correct the employer of Dudley Murphy's daughter Jennifer.

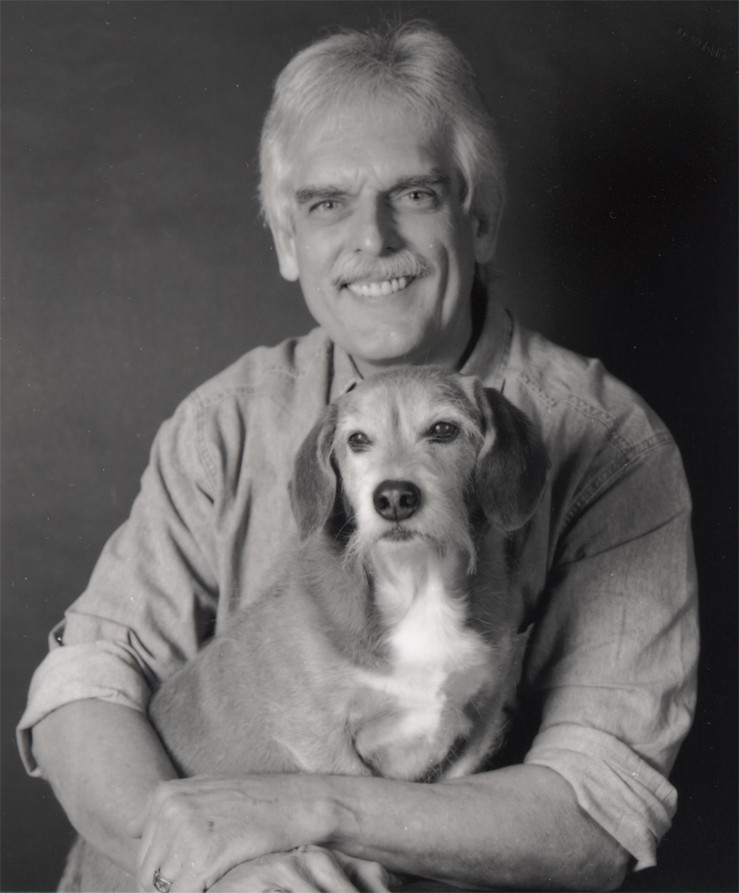

The over-used accolade “Renaissance man,” according to the dictionary, actually is “a person with many talents or areas of knowledge.” As a guitarist, singer, songwriter, poet, graphic designer, teacher, sculptor, potter, painter, photographer, conceptual artist, outdoorsman, author of short stories and guidebooks for collectors of antique fishing lures, Dudley Murphy surely met that strict definition.

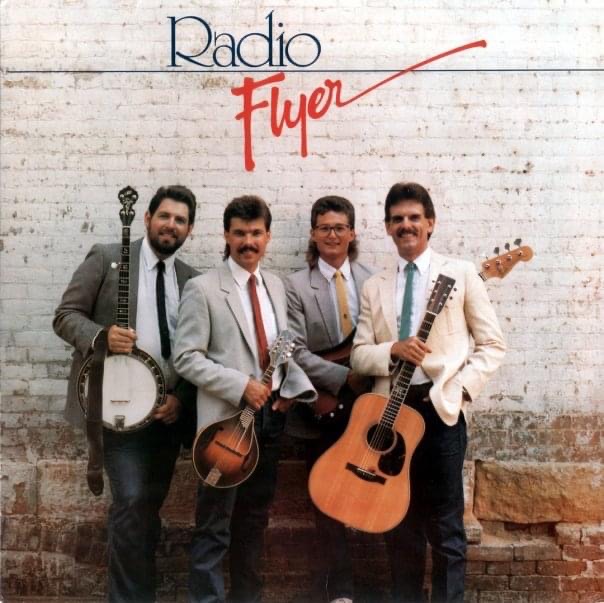

Dudley, who died Nov. 19 at age 82, was a popular professor at Drury University for 38 years, and before that, the educational curator at Springfield Art Museum. However, although he generously shared the billing and spotlight with fellow talented musicians, Dudley was the solid core of bluegrass musical groups, especially Radio Flyer, that won acclaim far beyond the Ozarks.

Yet, according to those who knew him best, Dudley put primary emphasis on basic aspects of life.

“Dudley had a strong sense of family. He was a Christian man, and all that came to bear on how he conducted his life, how he prioritized things,” recalls David Wilson, his Radio Flyer bandmate and close friend for more than 50 years.

“Early on in Radio Flyer, when we had a lot of success, a lot of people in the (music) industry really pushed us to take advantage of that and to give it a lot of time and effort. We had an actual meeting about it, and the takeaway was that we wanted to enjoy getting out and contributing to bluegrass music, to music in the Ozarks and in the greater world of acoustic musicians, but we didn’t want to sacrifice ourselves or our families on the block of success.

“It was a unanimous decision by all four members,” says Wilson. He was Radio Flyer’s versatile mandolin and fiddle player; Roger Matthews played banjo, and Steve Duede handled bass.

“We still got to have a lot of adventures, play a lot of big shows and festivals, be on national radio programs, have a lot of fun,” Wilson said. “We kind of alienated some people who were our supporters because they thought we were missing a great opportunity — but, you know, it was a decision that we all considered and made together. No regrets.”

Falling in love over music lessons

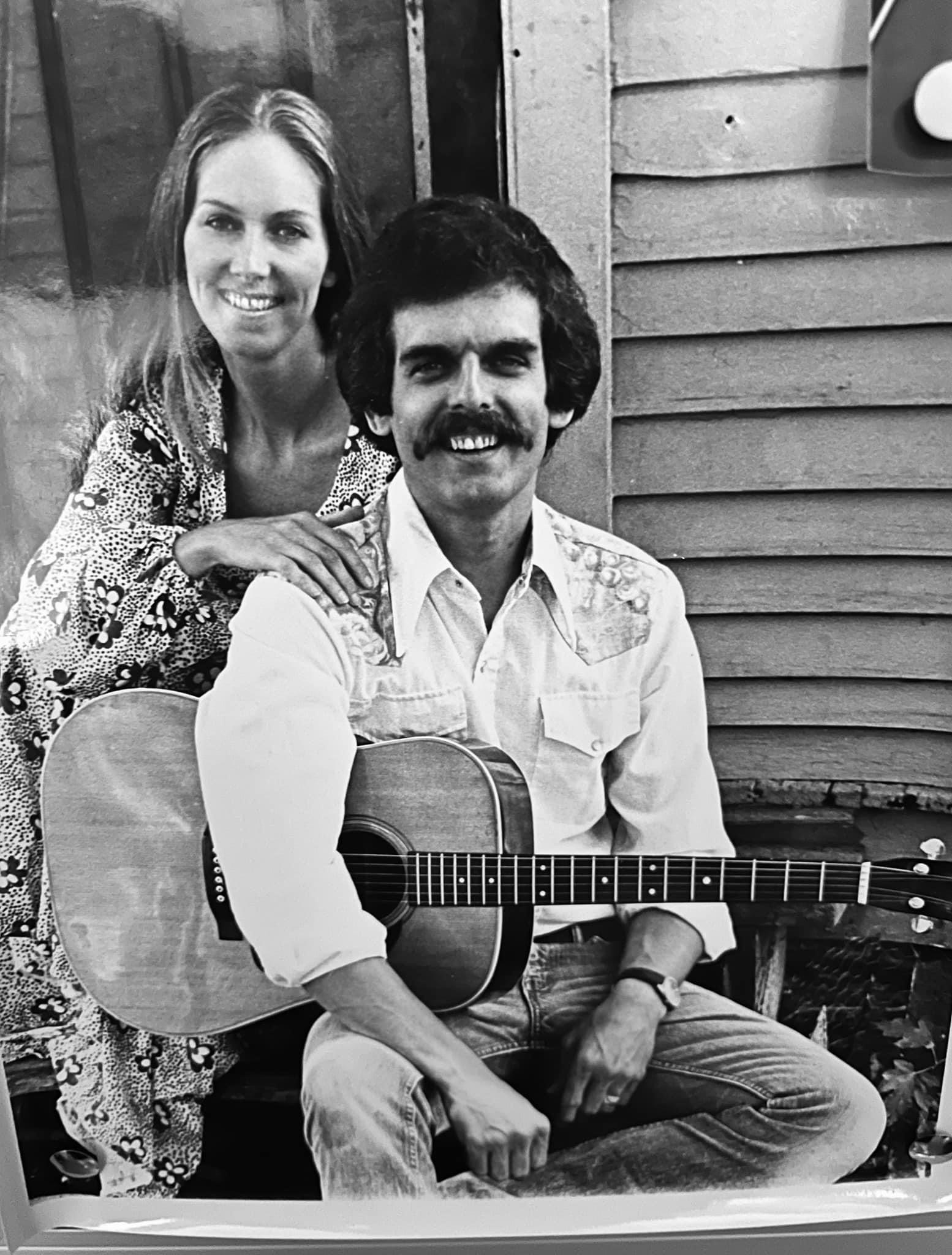

The family that Dudley cared about and focused upon was built with his wife of 55 years, Deanie, and grew to include their children, Jennifer and Quinn.

Deanie met Dudley in the mid-1960s when both were living in Tulsa. Dudley had been born in Kentucky and moved to Oklahoma as a teenager. While still in high school, he became interested in music — rock and roll, initially — and took up the guitar. In a rare instance of being the headliner, an early band was promoted as Dudley Murphy and the Fadeaways.

Dudley jammed with Tulsa musicians who later followed the road to fame, including Leon Russell and J.J. Cale. However, he became intrigued with the folk music movement that swept the country in the ‘60s and began haunting Tulsa coffeehouses and other venues where folk music was performed. Eventually, Dudley joined in.

“My younger sister, Gaylene, had gone to this coffeehouse and she told me, ‘You’ve just got to come see this guy! He is so good — his guitar-playing and singing are amazing!’” Deanie says. “So we went to see him — several times, in fact.

“Finally, we got our nerve up to ask him if he would teach us guitar. Very hesitatingly, he eventually said he would, at five dollars a lesson. I knew how to play basic rock chords. He taught us to finger-pick.

“Gaylene and I didn’t know how old Dudley was, but we both thought he was pretty cute. So we decided that we were going to have to find out how old he was, to see who should go after him. I won.

“We dated all that summer and until the next May when we got married. He continued to give us guitar lessons — and he charged us for every one, the little stinker!”

Dudley arrives in Springfield

Dudley’s day job was as a part-time illustrator and graphic designer for a couple of Tulsa advertising agencies. With Deanie’s encouragement, he enrolled at the University of Tulsa and earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in graphic design and sculpture.

Dudley’s first foray into Springfield was for a couple of semesters as an instructor at what then was Southwest Missouri State University, filling in for an art department professor who was taking a sabbatical leave. That whetted his appetite for teaching, so he returned to Oklahoma and earned a Master of Fine Arts degree from the University of Oklahoma.

Then it was back to Springfield for the 1970s to oversee classes at the Art Museum. He taught ceramics, both handbuilt and on the potter’s wheel; photography, painting, silk-screening and other artistic endeavors. He organized an annual art and craft festival to showcase the work of students and other locals. He even had a hand in the museum sponsoring an annual kite contest for three springs.

Dudley also pursued his own artistic expressions, employing unusual elements such as bales of hay, wooden fence posts, hair gathered at a barber shop, and rocks collected along Ozarks streams and on the shores of lakes in Michigan. SMS art department chair and News-Leader art critic Edgar A. Albin wrote of one of Dudley’s conceptual displays: “While Murphy’s sticks and stones statements appear casual and uncontrived at first glance, they soon emerge as assemblages by a sensitive designer, fully aware of his materials in space.”

By the 1980s, Dudley had moved to the art department at Drury College (now University), where he began a visual communication program, incorporating state-of-the-art computer gear to prepare students for careers in commercial illustration and graphic design.

Tom Parker chaired the Drury department. “Ostensibly, I was his boss, but I was not really his boss at all. Dudley was on his own trip, as teachers should be. He was the real deal. The kids loved him and felt they were well-served by having him as their teacher.”

Robert Price, who was a student of Dudley’s at Drury in the mid-1990s, describes Dudley as “very challenging in a very creative way, pushing students to learn their creative assets that they may not have been aware of, helping them grow and expand their creativity through the design process. He was always encouraging to everyone while helping them find their strengths.”

Price, originally from Springfield but now the creative director for an ad agency in Tyler, Texas, also developed a friendship with Dudley outside the classroom through their mutual interests in guitar and fishing. Dudley even served as best man in Price’s wedding.

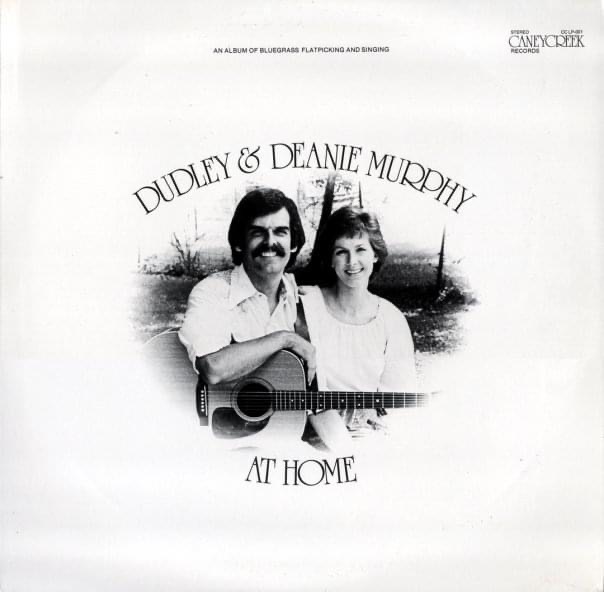

While all this was happening, Dudley continue to pursue his musical activities. Dudley and Deanie recorded a folk music album titled “At Home.” They played a couple of summers at Silver Dollar City as the Murphy Family Band, with Quinn, then in junior high, on fiddle and his younger sister Jennifer playing hammer dulcimer. Most significantly, the couple organized and performed with a bluegrass band, County Line, that was on local and regional stages through the ’70s and into the early ’80s.

That’s when Dave Wilson met the Murphys. He was transitioning from playing guitar in a rock band to learning about bluegrass. He remembers attending a Bluegrass Society of the Ozarks meeting at which Dudley was putting on a guitar workshop.

“Most people don’t realize it, but when Dudley was in college and starting to make his mark in the flat-picking world, he fell while climbing on some rocks and broke his index finger on his left hand. The doctor that set it didn’t realize that he was a guitar player, so he ended up with an index finger that he couldn’t really bend.

“Flat-pickers make heavy use of the index finger, but Dudley managed to do all of that fantastic, flashy, intricate, complex chord work with mostly just his middle, ring and pinky fingers. That blew everyone away.”

Wilson and some longtime friends formed a bluegrass group called the Dalton Boys. “When we first started out, it was pretty tragic,” he says with a chuckle. “We would follow the groups that were already established in the area, like County Line. Dudley’s group was the big show around Springfield at the time.”

The Dalton Boys gave way to the Undergrass Boys in 1978, and until 1982 that group enjoyed impressive success of their own in bluegrass circles. In addition to Wilson, the Undergrass Boys lineup included guitarist Bo Brown.

“I started hearing Dudley’s name when I went to the Walnut Valley Festival for flat-picking in Winfield, Kansas. When I found out he was from Springfield, I became a big fan. He was my first local hero who did what I wanted to do. Of course, he was operating at a much higher level than I was back then.”

Brown explains that the flat-picking bluegrass style of playing the guitar involves “picking out fiddle tunes on the guitar, picking out melody lines and fancying them up a bit and making them your own. Dudley was big in that world.”

Dudley finished second in the prestigious national flat-picking championship competition at Winfield in 1973 as testimony to his prowess. “He was just a stellar guy,” Brown says. “He kind of blazed the trail in this area for flat-picking guitar.”

By 1984, County Line “had kind of fizzled out,” says Deanie. “Dave Wilson called and said, ‘We ought to get a band together.’” Wilson, who had been playing at a Branson dinner theater since the breakup of the Undergrass Boys, remembers it this way:

“Roger Matthews had been working with me in Branson, playing banjo and emceeing the show, and we had been talking to Dudley occasionally about getting together sometime just for fun. So when the theater folded in the fall of ’84, we went over to Dudley’s house and jammed and had a really good time. And we thought it might be a good thing to make a going concern out of it.

“By the festival season of ’85, we had a pretty active schedule lined up as Radio Flyer.” (And, yes, the band is named after the iconic child’s wagon.)

When they first formed, Dudley, Wilson and Matthews were joined by Irl Hees on bass. However, Hees left for another band after a short time, and Duede stepped in and remained the Radio Flyer bass anchor until 2005.

That quartet’s first big break came in September 1985 when they won the “Best New Band” competition at the big Kentucky Fried Chicken Bluegrass Music Festival in Louisville, Ky. Second-place finishers in that contest were Alison Krauss and Union Station, who today are superstars.

“Of course, back then, she was just 14 years old and hadn’t won 28 or 29 Grammys yet,” Wilson says, laughing. “But after that we’d say, tongue-in-cheek, ‘Yeah, we’re those guys who beat out Alison Krauss.’”

The win did bring real results. “We were invited to play on the ‘Mountain Stage’ program on National Public Radio and on some other syndicated radio shows. We were on bluegrass magazine covers. We got lots of opportunities to play festivals. And we recorded the first Radio Flyer album. It was a good boost for us.”

Dudley brought his family along whenever he could.

“My sister and I grew up at bluegrass festivals, siding on hay bales, watching Dad and his band perform throughout the United States,” recalls Quinn. “We were really immersed in the music.”

Deanie chuckles over a photograph of bluegrass legend Bill Monroe holding an infant Quinn at a festival. “Quinn was a spitter-upper,” his mom says, “and we were thinking, ‘Oh, Bill Monroe’s beautiful suit…’ But Quinn didn’t spit up on it, thank goodness.”

However, there was more than music to family life for the Murphys.

They explored the Ozarks by hiking, canoeing and kayaking. Dudley introduced Quinn to fishing. At the Nov. 28 funeral service, Quinn told the crowd:

“It was during those fishing trips that Dad would talk to me about life — about God’s creation, about the beauty of Nature, about the peace he found in the sound of a gurgling stream. I realized later that Dad was utilizing that time we had together fishing to capture my heart. I was fishing for trout and bass; Dad was fishing for me.”

Dudley and Deanie bought an abandoned log cabin in Arkansas, meticulously marked the components before disassembling the cabin and then transported it in pieces to Missouri for reassembly on property they owned near Forsyth.

“It took a lot of years to put that cabin back together and chink it,” Deanie says. “The work had to be done before the ticks were out, and we had to end it when the OU (Oklahoma University) football season started. Dudley was a big fan.”

The OU games are a fond memory for Quinn: “When I was a kid, we would watch them on TV here at the house. Whenever Oklahoma scored, Dad would have to jump up and touch the ceiling.”

They continued to watch in later years, even when Quinn, who is an attorney in St. Louis, no longer was at the Springfield home. “I would have two cell phones charged, so when one battery ran down I could switch to the other, as we watched separately but still together.”

Basketball also became an important sport for the father-and-son duo, especially as Quinn started growing to his eventual height of 6-5.

“Dad put up a goal out in the driveway, and we would get out there and shoot. It was a shared interest and an excuse for him to spend some time with me. We would occasionally play one-on-one, and he would always beat me – until I was about 13 years old, and I started getting bigger and it became more challenging for him to win.

“He could see the writing was on the wall. So one day when we played a game of one-on-one, he beat me. And he said, ‘I’ll never play you again – because now I can always say that I beat you the last time we played.’ And he never did play me again.”

Quinn did continue to play. He starred at Parkview High School, and then, after a year at SMS, he moved to Drury and helped lead the Panthers for three seasons. “But for years after, Dad repeated to other people, ‘All I know is that I beat Quinn the last time we played.’”

Jennifer, who today is director of counseling at Maryville University in St. Louis, recalls Dudley’s late-night habits. “He was a night owl. He’d stay up writing and practicing.”

“Until two, three or four o’clock in the morning,” agrees Deanie.

Quinn saw it as “Dad was enjoying the day, and he wanted to squeeze the last drop of enjoyment out of it.”

Both offspring were pleased to be Drury students while their father was on the faculty.

“I loved it,” says Jennifer. “I would go bother him in class sometimes, put things on his bill at the CX. But mostly I was really proud that he was my dad because his students loved him, really loved him.”

Quinn says that he, too, was proud: “Dad was known as a student’s professor, and everybody liked him. It was enjoyable for me to see that. It was great, in fact.”

Jennifer does cite one failing by her father: “Dad was never on time. Not once. That was the one thing he didn’t do.”

Quinn says that while he was growing up, the family attended a Baptist church in Ozark, and “we would arrive 45 minutes into an hour-long sermon. And in a Baptist church, the only place left if you were late was front and center. So Dad would escort the family to front and center, we’d sit down, sing the closing hymn and leave. That’s why now I’m 15 minutes early to everything in my life.”

Another activity that Dudley shared with his son was fishing. And that was connected to another of his passions — collecting antique fishing lures.

His grandfather had whittled fishing plugs, and his father developed one of the first vibrating lures on the market in the 1940s. As an adult, Dudley became interested in fly fishing, and often tied his own lures, sometimes incorporating hair from the family dog and even from Quinn’s head.

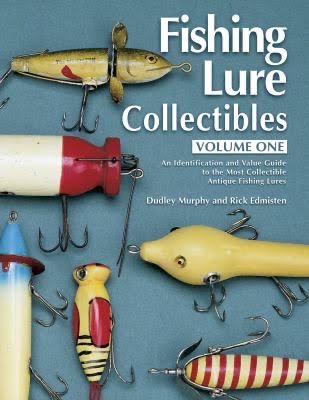

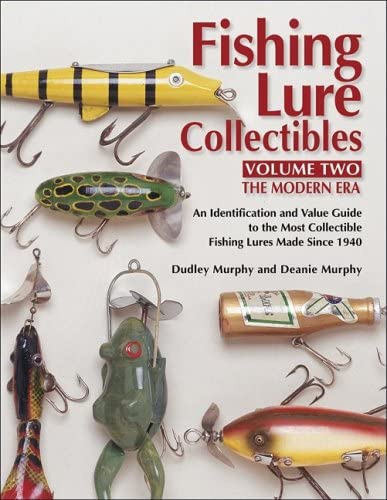

All the while, he collected old lures made by others and other vintage fishing gear, eventually amassing an array of artifacts that numbered in the thousands. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Dudley, along with a couple of fellow enthusiasts, published major books documenting the history and variety of fishing lures. They remain in print, and are considered bibles of the hobby.

Dudley, of course, applied his photography and design skills to make the handsome books worthy of prominent display on coffee tables rather than relegated to dusty bookshelves.

He also was a founder of the National Fishing Lure Collectors Club, which today numbers more than 5,000 members worldwide, and produced 56 issues of an impressively slick and colorful magazine for the club.

About three years ago, Dudley suffered a stroke. He recovered, but soon after was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease that slowly but relentlessly progressed the past two years.

Dave Wilson continued to visit Dudley, usually once a week, at home and then at the local nursing facility where he was moved early this year.

“We’d talk about music and all the things he and we had done. I found out about a lot of songs that he’d written but that nobody had recorded, and I learned some of them,” Wilson says.

The visits continued until the day Dudley died. “I am so very grateful that I got those chances to spend time with him,” Wilson says. “I got the chance to say all those things that I wanted to say, and not have regrets for not saying them one more time.

“I know where Dudley is. He had a big life, we had a lot of fun, we did a lot of music together, and I couldn’t be happier for him having such a wonderful life and being so well-liked and loved and respected. I don’t see any reason to be sad except for selfish reasons.”