This story is published in partnership with Ozarks Alive, a cultural preservation project led by Kaitlyn McConnell.

MONTE NE — A few of the last visible remnants of William “Coin” Harvey’s famed Monte Ne — a resort town in northwest Arkansas where he once began building a 130-foot-tall pyramid to serve as a time capsule after the fall of civilization — have disappeared into the past.

An iconic tower and remains once part of an area known as “Oklahoma Row” began being torn down the week of Feb. 20.

“Unfortunately, we weren’t able to find a solution that could overcome the costs involved to maintain the site,” said Jay Townsend, executive officer of the Little Rock District of the Army Corps of Engineers, in a news release. “Over the years as we worked to preserve the site, our rangers observed increased trespassing through the security fence and other dangerous activities. Vandals have covered parts of the structure in graffiti. It’s an incredible piece of history, but more and more, it’s become an attractive nuisance and safety hazard.”

While the land today is overseen by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, at one time Monte Ne was a town of its own.

“(Coin Harvey) laid out a miniature city including two large log hotels, a clubhouse, bank, store sites, swimming pool and built a pavilion for public speaking,” noted the Madison County Record in 1936. “He built a railroad station and a short line to connect the resort with the St. Louis and San Francisco railroad. He brought to Monte Ne at least two nationally recognized conventions besides the Liberty party convention in 1932 at which he was nominated for president.”

Yet today, it is nearly gone.

“History isn't just about buildings and artifacts. It's also about the people who lived it and the stories that come from them,” said Angie Albright, director of the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History. “One of the many reasons the Monte Ne history is important is how it fits into the story of tourism and settlement in the Ozarks. Monte Ne is so representative of all the people who have ‘discovered’ the Ozarks and then knew its natural beauty could draw others.”

Who was Coin Harvey?

While signs still point to Monte Ne, no one is alive who saw its heyday firsthand. The resort was only one of many ventures and careers by Harvey, who was born in 1851 in today’s West Virginia and grew to such prominence that he “could have had almost any political office in the land, had he asked for it,” noted the Baltimore Sun in 1930.

Before Harvey arrived in Arkansas, he spent time in careers including mining, law, education, politics, promotions (where he ran a failure of a carnival, it’s been said) and development (in Colorado, he was involved in the famous Mineral Palace — look it up — and allegedly designed an 11,000-pound statue made from coal).

Harvey’s biggest claim to fame, however, came through the free silver movement.

“Like other western business leaders, he believed that abandoning the gold standard and returning to the free coinage of silver would restore prosperity,” notes the Encyclopedia of Arkansas. “In 1893, Harvey moved his family to Chicago to devote his time to the cause. He began writing and lecturing, arguing that the U.S. Treasury should buy all silver offered at a set price and issue silver certificates backed by the deposits.”

He published “Coin’s Financial School,” an 1894 book that — through illustrations and characters — conveyed why silver was a better money standard for the country. It was “an instant hit and bestseller,” wrote biographer Lois Snelling in “Coin Harvey: Prophet of Monte Ne.”

“‘Coin’s Financial School’ is notable for three things,” Snelling noted in her 1973 book. “First, it gave to the author a new name. Since its appearance, Coin Harvey has become a familiar name throughout the country, while William Hope Harvey is hardly known. Second, the book paved the way for the first presidential campaign of William Jennings Bryan on the Democratic ticket in 1896. Bryan, ardently advocating bi-metal coinage, made his famous ‘Cross of Gold’ speech during the campaign. In the three-hour-long oration, he pleaded for ‘free coinage of silver at 16 to 1.’ The campaign slogan became ‘Sixteen to One’ and serving as Bryan’s faithful personal adviser was none other than Coin Harvey. Third, the book sold nearly 2,000,000 copies.”

After Bryan lost his presidential bid, Harvey ultimately made his way to Arkansas and purchased 320 acres at a place that was ironically known as Silver Springs. Impressed with the scenic beauty and believed medicinal resources, he announced plans to develop a health resort on the property. It would be named Monte Ne, which was said to translate to “mountain water” in other languages.

In the era of medicinal springs, the “health-giving properties are established beyond question,” noted the People’s Banner newspaper in 1901. “The theory of the water is that it is practically pure, nearly as pure as distilled water, with the advantage over the latter that it contains the earth’s ozone or electricity and cleanses and purifies the system.”

News of the soon-to-come development hit newspapers across the country, including at home in Arkansas:

“The great author and speaker, Coin Harvey, has invested in Benton County real estate and will establish the finest summer resort in the west,” proclaimed the Green Forest Tribune in December 1900.

“Last summer Mr. Harvey stopped at Rogers a few weeks for his health, and while there visited the famous Silver Springs. Their natural advantages impressed him as an ideal place for a summer resort and he purchased the springs, together with a large tract of land adjoining.

“He has gotten out specifications for a 200 room hotel, a large lake a mile square, a turnpike road from Rogers; a distance of five miles.

“The Frisco road has agreed to give him the same advantages it gave Eureka, and as that road has now bought the A & O they will probably extend it to Silver Springs on southeast.

“Mass meetings have been held at Rogers and Mr. Harvey will receive the undivided support of that site in his new movement.”

The development of Monte Ne

Even before Monte Ne opened for visitors in 1901, it already received recognition as a destination.

A newspaper advertising property for sale used it as a reference point; Harvey wrote a letter to the editor — railing against an amendment that would allow Arkansas municipalities from issuing bonds — hailing from Monte Ne, even though the name was still Silver Springs at the time.

The anticipated resort opened in May 1901 in “a blaze of glory,” as the Springfield Republican noted with a front-page story.

“Over one thousand invitations were issued and more than two hundred couples from twenty cities and towns in a half dozen states are present to participate in the festivities of the occasion,” the paper previewed on the morning of the event. “The ball being given tonight is the most brilliant social event that has ever occurred in this section, and marks the beginning of a new era in the social world of Northwest Arkansas.”

According to the Madison County Record, shortly after the resort opened, Harvey formed Monte Ne Investment Company and sold lots for affluent visitors “in almost every section of the United States” to build summer cottages.

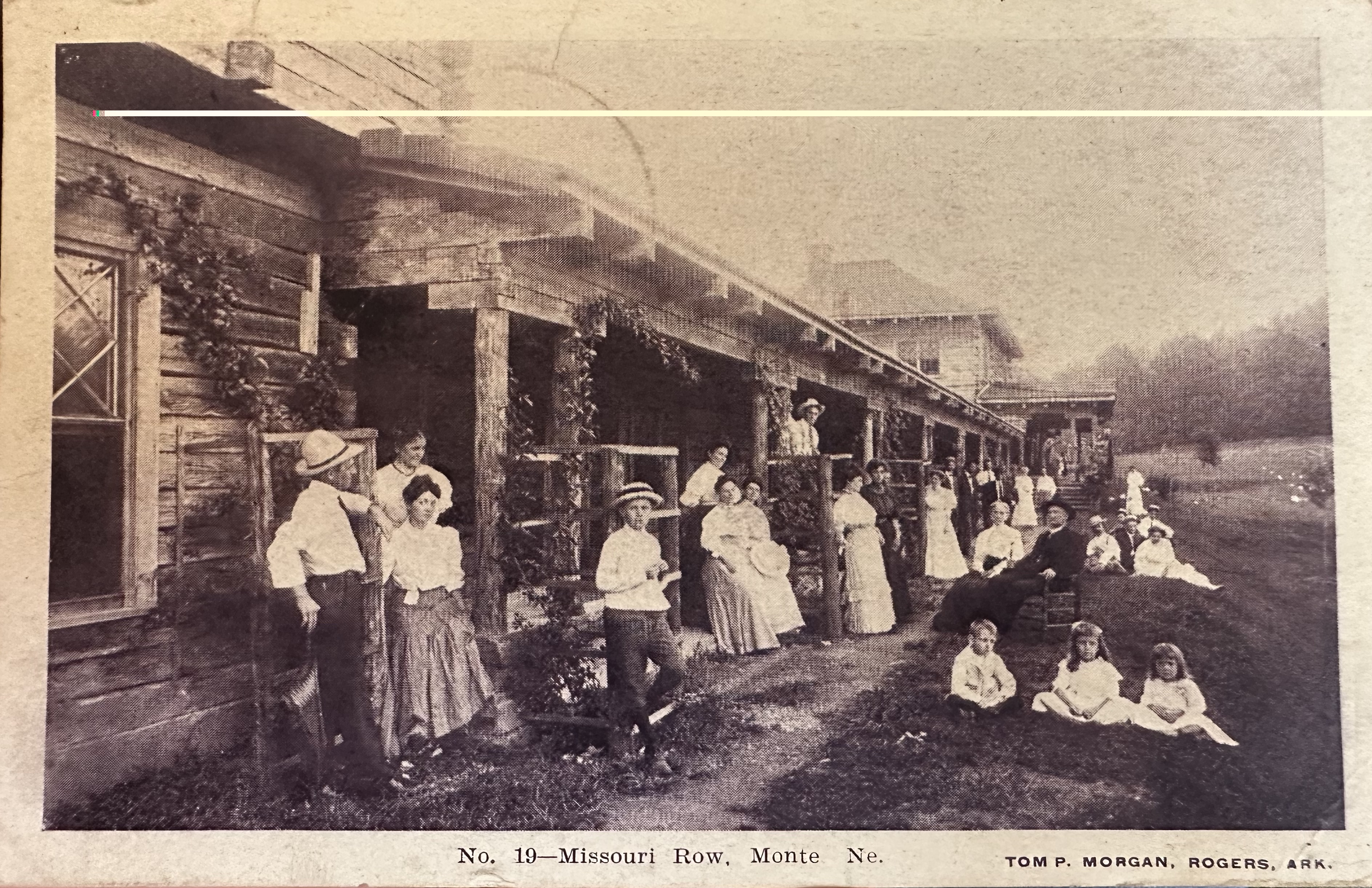

“The first of his hotels was completed in 1901 and opened in May,” noted The Joplin Globe in 2018. “The three-story Monte Ne Hotel boasted an outside doorway for each room and was surrounded by wide porches. In three years, Harvey hired A.O. Clarke to design four ‘cottage row’ hotels to be named for the five states surrounding Arkansas. The first was the Missouri Row. It was 305 feet long and 46 feet wide, and it was made of logs with concrete floors and a red tile roof. It opened in September 1905. Rooms went for $1 a day and $6 a week. In two years, he had begun the Oklahoma Row with 40 rooms, each with a distinctive fireplace.”

According to the Daily Oklahoman in 1963, those log accommodations “were described at the time as the longest log buildings in the world.

A spur Frisco line from Rogers was added in 1902, making transportation to Monte Ne even easier in days before good roads and cars on which to drive them. Once at Monte Ne, visitors traveled by gondola — imported all the way from Italy — to the resort.

“At the height of its popularity, Monte Ne featured a golf course, dance pavilion, tennis court, and the first indoor swimming pool in Arkansas,” wrote historian Brooks Blevins in his book, “A History of the Ozarks: The Ozarkers.”

Changing times and pyramid-building

Monte Ne’s years as a glittering resort were relatively short-lived. Challenges unfolded over several years, including the demise of the railroad, World War I and issues with the stockholders of the hotel company. The latter caused the Monte Ne club property — which included hotels and other holdings, but not Harvey’s own acreage — to be sold in 1927 to satisfy a mortgage.

For around five years, portions of the Monte Ne property were home to the Ozark Industrial College and School of Theology, a co-ed vocational school sponsored by the Pentecostal Holiness Church. That endeavor was also short-lived and closed by 1932. Parts of the former resort were later operated in various capacities in the following years.

But other efforts in Harvey’s own life were rolling down the road by that time. Monte Ne was where the Ozark Trails Association was founded in July 1913, and Harvey long served with the good-roads movement, perhaps in an effort to get more people to Monte Ne. He did not abandon his political beliefs or concern for the world: in addition to other publications, in 1915 he released “The Remedy,” to help encourage character-building.

“The project as outlined by Mr. Harvey is no small one,” noted a piece in the A.H.T.A. Weekly News from April 1915 that was reprinted from the Joplin Globe. “He is working on the premise that things are not growing better in the world, but growing worse. In his own words, ‘The great army of reform, peace and justice is retiring before the army of Evil,’ and ‘Believing that I see where in the forces of Good need help, I wish to assist them by making plain an auxiliary plan and creating an organization to take charge of the work.’”

Later, those thoughts built to the project Harvey was convinced was perhaps the most important of his life: Building a pyramid — later referred to with a capital P to give it prestige — at Monte Ne that would outlive the demise of civilization.

“Long after our twentieth century civilization is gone and perhaps forgotten, a permanent and complete record of it may be found in a 130-foot pyramid being built here,” noted the Mountain Air newspaper. “Even as the ancient inhabitants of Egypt preserved records of their civilization in the massive pyramids in the Nile valley, will this towering pyramid in the foothills of the Ozarks preserve that of the twentieth century.”

On it, a plaque would read: “When this can be read, go below and find a record of and cause of the death of a former civilization,” the newspaper said. “Similar plates will be placed still lower, reading: ‘Go within.’”

The pyramid was to contain a variety of artifacts, although the list varies by source. “Inside he would place an automobile, a phonograph, a Bible, and various books, with guides to help the finders decipher the English language,” once noted a Pennsylvania paper.

As Ozarks authority Otto Ernest Rayburn put it in his book “Ozark Country” from 1941, “the pyramid was to be a storehouse of civilization.”

Work on the structure began in 1926. An initial phase of the project was celebrated in 1928, when a “new stadium” was dedicated with a crowd of 500 people (including presentations by students from the aforementioned Ozark Industrial College and School of Theology). Today, that place is commonly known as the amphitheater.

“The stadium is built of concrete for the purpose of strengthening the base of the foundation of the Pyramid and for use of public gatherings,” noted the Star Progress. “It will seat 1,000 persons.”

Sadly for Harvey, the pyramid never came to be. Funds were a problem, an issue that was exacerbated by the onset of the Great Depression in 1929. Harvey, too, had his own challenges, including a number of serious health issues.

They, however, did not keep him from running for president in 1932 on behalf of the Liberty Party. He amassed 53,425 votes, but lost to Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In 1936, Harvey died at Monte Ne. In the following months, much of “his” town was sold to pay his debts, including nearly 15 years of back taxes.

His widow, May Leake, served as his secretary for around three decades before they married a few years before Harvey’s death. She ultimately moved back to her hometown of Springfield.

Leake was (hopefully) a point of joy in Harvey’s troubled personal life. Even though he despised divorce and wrote of its contributions to societal ruin, he finally filed for one against his first wife, Anna, in 1929. She had left Monte Ne shortly after it opened — nearly 30 years before — and refused to come back.

Lasting legacy

Even though the story had faded by the time of Harvey’s death, there were still people thereabouts who knew of him (and his cantankerous personality, it’s been said) very well. His story, however, came into light in a renewed way some 25 years after his death.

The reason: The creation of Beaver Lake — containing 31,700 acres of water and 483 miles of shoreline, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch said — was destined to absorb much of Monte Ne’s remains.

“Scores of hamlets and small towns in Arkansas will be covered by Beaver reservoir, but none will have the history and importance of Monte Ne,” noted Oklahoma’s Capitol Hill Beacon in 1962.

There wasn’t much left operating in Monte Ne by then. In a way, it was the fulfillment of Harvey’s fear. But there was no pyramid to tell about the demise of his civilization.

“Army engineers say that within three years or so, the waters of Beaver Reservoir will roll over Monte Ne,” noted the Baxter Bulletin in 1960.

Work on Beaver Lake began in 1960 and was included in the comprehensive plan for flood control and other purposes in the White River Basin by the Flood Control Act of 1954. It was “one of five multi-purpose projects constructed in the White River Basin for the control of floods, generation of hydroelectric power, public water supply, and recreation,” notes information on the website of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which oversees the lake.

Work took years, during which time there were many opportunities to reflect on the history of Monte Ne (and move a few structures).

“At flood stage, the new lake will engulf Monte Ne, burying it and the legend of its most fabulous citizen, William Hope ‘Coin’ Harvey, under several feet of water,” noted the Sunday News and Leader in 1961. “Well, maybe not the legend. It’s hard to bury a legend that won’t die, and that of ‘Coin’ Harvey is still pretty lively.”

They were ironic words, since one of the biggest challenges — literally and figuratively — about the drowning of Monte Ne was Harvey’s tomb. He was buried near one of his sons, who died several years before him in a railroad accident. There were debates locally as to whether or not Harvey would want his tomb relocated, or simply let the rising lake waters cover him forever.

“There were those who complained about the removal,” wrote biographer Snelling. “Coin Harvey, they said, had cherished the thought of having his son there in the quiet valley all those years and it seemed a bit like sacrilege to move him now. He had carefully arranged to have his own body imbedded in the concrete and left in his beloved valley, secure against the ravages of time, and it just didn't seem right to go against his wishes. The law said it had to be done, but everybody suspected that if Mr. Harvey could have a voice in the matter he would choose to remain on the valley floor.

“‘The water will be fifty feet above him,’ the Engineers warned. ‘At flood stage it could rise to 65 feet.’ But they, too, having learned the story of Coin Harvey, suspected that he would prefer to be left where he was. Throughout his lifetime and even in death he was not permitted to see a dream come into fulfillment.”

In the end, due to regulations, the 40-or-so-ton concrete crypt was moved about half a mile up a hillside.

In 1978, the Monte Ne’s historic relevance was established on the federal level with its addition to the National Register of Historic Places. In a section on the application — which largely focused on the amphitheater — an “x” was next to “Other” in the place where its current use was asked.

Typed next to that was simply two words: “Under water.”

Up to today

In recent years, the crypt, some foundations, and skeleton-like pieces of Missouri Row and Oklahoma Row were the few Monte Ne landmarks left in place and above lake water.

While perhaps not all knew the story of why they were there, the structures were regularly visited, proven by the colorful vandalism on the tower, despite a high fence that was added several years ago.

While foundations from Missouri Row are still visible, those famed remains of Oklahoma Row will also disappear into the past.

“The decision to remove the Oklahoma Row and Tower was not an easy one,” said Townsend, of the Corps of Engineers. “But continuous exposure to high lake waters over the last decade have contributed to the dangerous conditions along Oklahoma Row. It’s only a matter of time before things start falling on their own.”

In the news release, Townsend stressed the importance of historical preservation, and efforts to save details of Monte Ne in connection with the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History and Rogers Historical Museum, as well as the Arkansas State Historic Preservation Officer.

According to Albright, director of the Shiloh Museum, the work is a collaborative effort that will be organized in phases.

“Both the Rogers Museum and Shiloh are helping to identify architectural features that are unique and possibly interesting to save, such as the porthole windows on the third floor, perhaps a fireplace or two, though covered in graffiti, and the concrete sewer and water pipes,” Albright shared via email. “We are well aware that as the demolition begins the structure may not be able to withstand ‘cutting out' those pieces.

“The Corps is being very responsible and their contractor is going to do their best to save a few things. One of the Corps employees is an archeologist, so he (and all of us) are also very cognizant of possible archeological finds at the site. That work was done years ago, but with time and erosion, you never know what might turn up.”

Later, Albright said, the museums will help create displays and interpretive signage and a trail.

“We will assist in developing the interpretation and signage that tells the story of what was once there, and try to help visitors envision life before Beaver Lake arrived,” she writes.

Until then, the clock ticks to destruction. Just as Harvey said it would.

Resources

“A History of the Ozarks: The Ozarkers,” Brooks Blevins, 2021

“A monument to the world’s folly,” R. Frank Harrel, The Baltimore Sun, Sept. 14, 1930

“At Monte Ne,” Arkansas Democrat, July 26, 1901

“Beaver Lake,” U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, accessed Feb. 19, 2023

“Beaver Lake will cover Harvey’s dream,” Baxter Bulletin, Sept. 15, 1960

“Blaze of glory,” Springfield Republican, May 5, 1901

“‘Coin’ Harvey, Gaye Bland, Encyclopedia of Arkansas, accessed Feb. 19, 2023

“Coin Harvey’s estate is sold to pay his debts,” The Madison County Record, May 21, 1936

“Coin Harvey’s new enterprise,” The People’s Banner

“‘Coin’ Harvey’s new resort,” The Green Forest Tribune, Dec. 1, 1900

“Coin Harvey, prophet of Monte Ne,” Lois Snelling, 1973

“The death of Monte Ne,” Jim Billings, Sunday News and Leader, Dec. 10, 1961

”The end of a utopian dream,” Dickson Terry, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Nov. 25, 1962

“From ‘Coin’ Harvey,” Arkansas Democrat, Feb. 12, 1901

“Harvey’s prophecy comes true,” Daily Oklahoman, Oct. 13, 1963

“Harvey, ‘splendid failure,’ dies in Arkansas retreat,” Springfield Leader and Press, Feb. 12, 1936

“Monte Ne,” application for National Register of Historic Places, 1978

“Monte Ne (Benton County),” Allyn Lord, Encyclopedia of Arkansas

“Monte Ne club property to be sold,” Star Progress, Feb. 3, 1927

“Monte Ne Railway,” Thomas S. Duggan, Encyclopedia of Arkansas, accessed Feb. 20, 2023

“Monte Ne was the dream of ‘Coin’ Harvey, Bill Caldwell, The Joplin Globe, April 28, 2018

“New stadium dedicated at Monte Ne,” Star Progress, Aug. 16, 1928

“Once bustling resort town dwindles to only one store,” Robert V. Peterson, Capitol Hill Beacon, Dec. 23, 1962

“Ozark Trails Association will meet at Independence June 7,” Independence Daily Reporter, Feb. 26, 1915

“Ozark Industrial College and School of Theology,” Allyn Lord, Encyclopedia of Arkansas, accessed Feb. 19, 2023

“Sara of Famed ‘Coin’ Harvey recalled as new lake engulfs his ‘paradise,’ Grover Brinkman, Evening Herald, Oct. 19, 1964

“The Remedy,” A.H.T.A Weekly News, April 29, 1915

“To preserve glory of 20th century,” Mountain Air, May 18, 1929

“United States presidential election of 1932,” Britannica, accessed Feb. 21, 2023