OPINION |

I’ve covered local sports roughly the same number of years Keith Guttin has coached baseball at Missouri State and have always enjoyed talking about the game with him. I always learn something, which is not surprising considering he has 1,369 career victories and I have zero.

It’s safe to say we’re both traditionalists and not always excited about change. For instance, baseball had been played without a clock for more than 100 years and seemed to be just fine. The timeless nature of the game was one of its beauties. Or so it always seemed.

The idea of installing clocks on the outfield wall seemed outrageous and unnecessary. But here we are in 2023 and clocks now rank with hot dogs and cold beverages as ballpark staples.

But after watching one full season of minor-league baseball with a pace-of-play clock and almost a full season of a college season with one, I'm convinced that quicker is better for everyone. Guttin, in his 41st season as Bears’ coach, agrees.

“I think the clock is helping the game,” Guttin said following a recent Bears’ game at Hammons Field. “That’s as a traditionalist, purist, old-school person that doesn’t think the clock really belongs in the game. But I can say that in college, it’s probably a good idea.”

There’s been a 20-second clock with the bases empty in college baseball the last few years, though it was rarely enforced. Some schools didn’t have clocks at their fields. This year, the clock rule is being enforced, regardless of baserunners.

Just like what happened in the minor leagues last year and is happening on the Major League level this season, the world didn’t end when pitchers were forced to be on the mound and ready to pitch and hitters no longer could step out and fiddle with their batting gloves between every pitch.

Duration of games is dropping

Minor league games averaged 25 minutes less in duration in 2022 compared to the previous season. College games are a bit harder to measure because some are shortened due to run rules or scheduled for seven innings. Some are going to be three hours-plus, no matter what, if pitchers are unable to locate the strike zone.

“I feel we’ve had really short games or really long games, which can come from a number of things,” Missouri State designated hitter Cam Cratic said. “That can be because of a lot of balls, lots of hits or errors in the field. But I do feel like the amount of quick games we’ve had has gone up for sure.”

According to Jeff Williams, associate director for media coordination and statistics for the NCAA, the average game time in Division I in 2022 was 3 hours, 2 minutes. The average in 2023 is 2:49 for a difference of about 13 minutes. Williams said that as teams play postseason tournaments, the average likely will increase because postseason games typically last long.

“Still, it doesn’t appear that it will get that close to the three-hour mark on average for the season,” Williams said.

Williams also ran the data for the Missouri State games, with the 2023 average of 2:53 five minutes shorter than a year ago.

There's still gamesmanship between pitchers, hitters

But for those who have been to Hammons Field, games have seemed to move with a much better rhythm with the 20-second clock between pitches. The batter is required to be in the box by 12 seconds or risk having a strike called. The pitcher must beat the clock or have a ball assessed to the count.

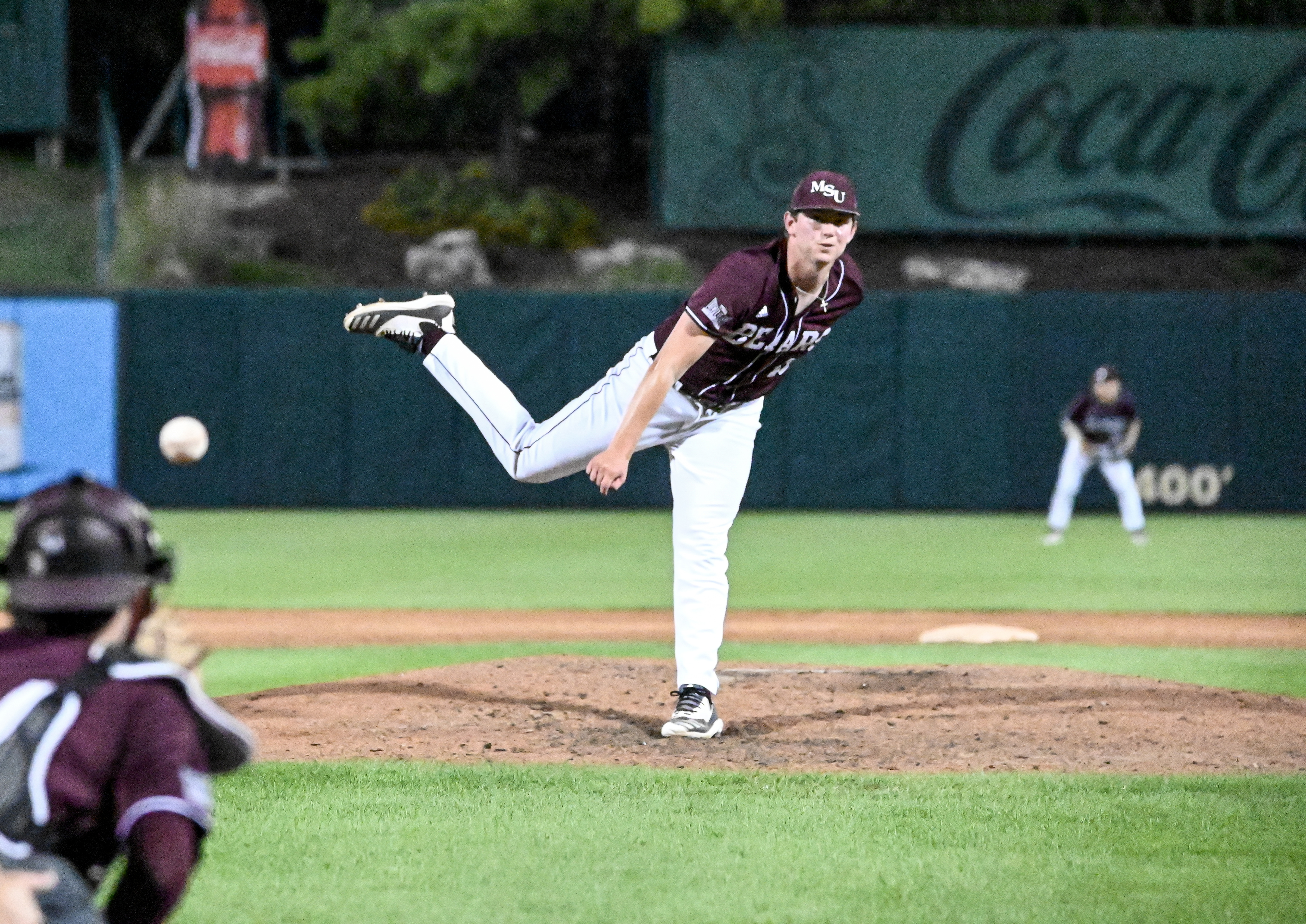

“At first it was kind of different,” Missouri State pitcher Hayden Minton said. “As the year’s gone on, we’ve adjusted to it. We preach a quick tempo anyway, so it’s kind of helped out our pitchers.”

Minton, one of the Bears’ weekend starting pitchers, said a few opposing hitters will try to disrupt rhythm by stepping in as late as possible or by using their one-allowed timeout just before a pitch is thrown.

“Sometimes if you get into a really good rhythm, the (opposing) coach will call timeout,” Minton said. “That just makes for a waste of a timeout with their players.”

Bears pitching coach now a fan

Missouri State pitching coach Nick Petree, an All-American during his pitching career for the Bears (2011-13), said the clock wouldn’t have bothered him. He worked quickly and has preached that same approach with his staff.

It was still a learning process for the pitchers and the coaches the first portion of the season.

“I think the clock has been good. It’s sped up the game,” Petree said, noting Missouri State pitchers have only been penalized two or three times all season. “I didn’t like it at first, but now I think it’s a pretty good part of the game to get games moving.

“It’s helped the game more than hurt it.”

The biggest adjustment has probably been made by hitters

Hitters probably have been forced to make a bigger adjustment.

“At first it was really tough,” Cratic said. “We talk a lot about funnels and getting yourself to reset if something doesn’t go your way. Or even if something does go your way, you want to reset and be neutral. For me, it was challenging to find a way to have my whole routine, pre-pitch and between pitches.

“Now I’m just trying to think, if the pitcher has to get ready earlier just be ready before the pitcher is. I rarely step out of the box between pitches. I kind of just stay in there and wait for him and stay ready.”

Cratic said he doesn’t remember a Missouri State hitter getting a strike call for a violation.

“The umpires have done a good job, if you do waver,” Cratic said. “They’ll say, ‘I need you in the box.’ You’re like ‘OK.’ I err on the side of just staying ready, the whole time.”

The clock is becoming the new norm

It won’t be long before baseball with the pace-of-play clock will be the new norm, something that at least on the college and professional levels will hardly be noticed.

“It’s gonna be weird when you see it a few years from now,” Springfield Cardinals manager Jose Leger said. “Right now, it is becoming the new norm. And anyone coming from college to the professional level is going to be ready to adapt to it because they’ve already been used to it.

“There is still a little bit of adaptation time when we started the season. But right now, our guys are in a groove. It makes the game go quicker. Batters have to be attentive and ready to go. It’s a better tempo of the game.”

Bears contend for a top Valley finish

Missouri State enters the final two regular season weekends of the Missouri Valley Conference campaign in second place. The Bears (29-17 overall and 16-5 in the Valley) play at third-place Southern Illinois (28-21, 13-8) this weekend with games at 6 p.m. Friday, 5 p.m. Saturday and 1 p.m. Sunday.

Missouri State plays host to first-place Indiana State (33-12, 19-2) next Thursday-Saturday (May 18-20), with games set for 6:30 p.m. the first two nights and 2 p.m. for the series finale at Hammons Field.

The Valley Tournament is set for May 23-27 at Indiana State.