This story is published in partnership with Ozarks Alive, a cultural preservation project led by Kaitlyn McConnell.

RURAL TEXAS COUNTY — Connie Blaylock Wallace’s hands may hold brushes laden with paint, but it’s really her heart that creates scenes of Ozarks history.

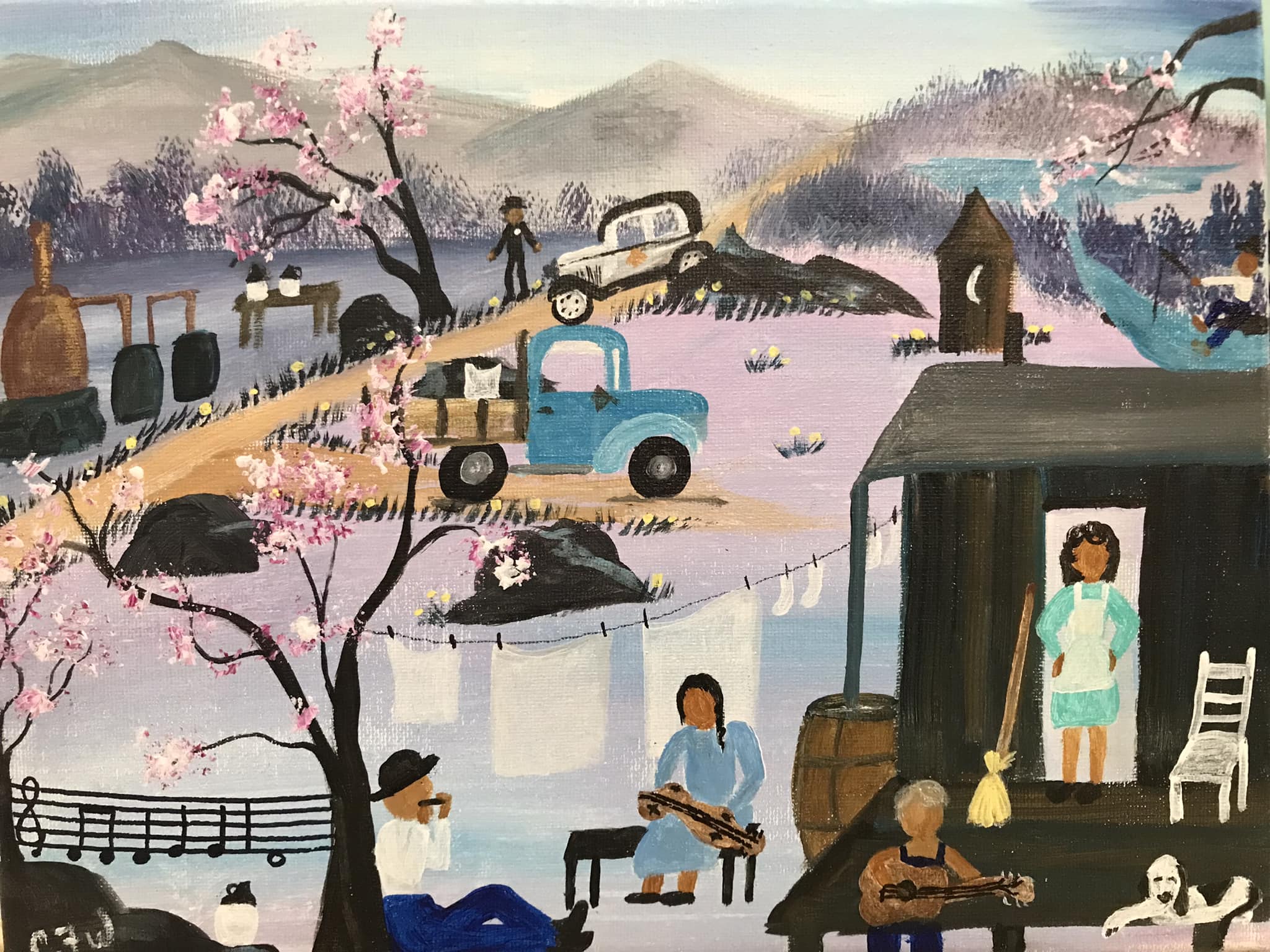

The images aren’t always literal, featuring faceless people and bright hues of blue, pink, red and purple, but they are real to Blaylock Wallace. Now 62, she was one of 14 children in a rural Ozarks family that did a lot with a little.

Her father was a preacher, taking the family from town to town to hold revivals and services — in churches when possible, or beneath brush arbors the family built.

While cents were scarce, there was plenty of love and humble pride in the connections they shared. And about four years ago, canvases showcasing those manifested memories began to emerge after Blaylock Wallace decided to paint, something she’d always had an interest in doing.

“The paintings, for some reason, they reconcile,” she says. “You can’t imagine the joy that they bring to me — just to pick a day that I remember and just put it down.”

An example is on her living room wall: a scene from the nearby town of Licking, which shows a carnival, soldiers coming home from war, and a parade, a prayer meeting and even a rodeo. It’s a way for a collection of memories to be found in one place.

“I really do think people are striving for a simpler way of looking at things,” she says. “People are just kind of mean about different aspects of life, and there’s no need for it. I think folk art brings a simplicity into it, and they look at it and think, ‘Oh, that’s a happy place.’

“I’ve had people say that before – ‘I want to live in that turquoise world.’”

A foundation for life — and future art

Blaylock Wallace was born in 1960. She was the family’s sixth child, a middle daughter in her large family, which raised a baker’s dozen.

“I was born in Salem on the kitchen table with a midwife,” says Blaylock Wallace from her rural Texas County farm. “I talked to my sister because you don't remember when you're born; she said that I was the last one of the older children that were born at home. Then Momma started having kids in the hospital. Life was a lot different back then.”

Their daughter doesn’t know for sure how many generations the family ties to the hills, nor how her parents met, but Billy and Joyce Blaylock were of the Ozarks. Blaylock Wallace also says that her father felt a calling from an early age to preach. He was not the only family member in the ministry, as his mother-in-law Ethel Richter also served souls.

“My granny was a charismatic preacher. She weighed about 90 pounds at the most — 90 pounds. And she and Daddy would have a revival together,” says Blaylock Wallace, who says her father leaned more towards Pentecostal preaching, although he never officially claimed a denomination. “Granny Ethel would speak in tongues, and he would interpret.”

Her father’s response to the call of ministry took the family on the road, eventually traveling in a wood-paneled station wagon as they went from one town to the next.

“My earliest memories were of Daddy preaching on the waterfront in St. Louis,” says Blaylock Wallace, sharing a painting she did in memory of those moments called “The Young Pastor.”

For the first years of her life, Billy Blaylock moved his family back and forth from Salem to St. Louis. When his daughter was about five, however, the family went farther south, to about 30 miles above the Missouri-Arkansas state line, where they stayed for several years.

“We moved down in a '57 Chevy car with stuff just tied all to the top,” recalls Blaylock Wallace, of a trip with children piled throughout the car.

“Mom and Dad had either eight or nine kids by that year. And so in the car, Mom had one on her lap — you know, car seats were not even thought of back then. So Mom had one on her lap, she had one at her feet, we were holding children.

“They told us we could take one toy, and I brought my doll house. It was strapped to the top of the car and fell off on the way down here from St. Louis. Daddy stopped and tied it back on the car.

“We had no idea where we're going to live. That is one very vivid memory. I remember being a little afraid, thinking, ‘Where are we going to live?’ He just stopped at the store and asked if anybody locally had a house for rent. Thank goodness, they did and we rented a house. When we got settled in, he took plywood and restructured my doll house for me.”

It was a life that was simple and without many modern conveniences, but a time of life that Blaylock Wallace looks back on as one of joy.

“We literally washed in the river. I don't remember having any bathtub in that house at all,” she says. “We eventually must have had the electricity hooked up because Mom washed on a wringer washer.

“If you read about different people, you know, they're like, ‘Oh, well, everybody had electricity in the early '60s.’ Poor people did not, especially people that moved from rental homes and couldn't afford each time to pay the deposits on the electricity. But we didn't really know any difference, so I didn’t care.”

Food could be a challenge for the large family, but they were assisted by a former federal program Blaylock Wallace refers to as “commodities” that helped those in need.

“When we were kids, we got commodities,” she says. “Once a month, you went … and you got flour, rice, staples of life; canned chicken, peanut butter, cheese. We loved commodity day. My mom was a brilliant cook, and she used it to the fullest.”

There were many moves during that period. “In my second-grade year, we moved from Hunter to Poplar Bluff, to Naylor to Poplar Bluff and back down to Hunter,” she says. “So I had five moves in my second year, and that's the most that I ever remember.”

At various times during her growing-up years, the family would load in the car and travel to a place to potentially hold services when Billy Blaylock didn’t have a regular church at which to preach. It was a family effort once they arrived: If there wasn’t a church house, the family worked together to build a brush arbor, and children helped pass out flyers to let locals know about services.

“We all helped; we worked hard from the time we were little,” she says. “We would make flyers, handwritten flyers, and put them up in whatever little town we were in about when revival would start.

“He would get four trees that were about as big as what he wanted the area to be, and then cut and try to leave a limb where another one would rest inside. Then you might probably have to have one in the middle, too, a prop or something to hold it up — which, none of them ever fell down, so he obviously knew what he was doing.

“On the top, there would be cross pieces, thinner ones. And a lot of times he would strip those out with a pocket knife. Then we would throw branches up on top of the roof of it.”

Preaching beneath those branches or inside local churches wasn’t the only work Blaylock Wallace’s father did to support his family. He sold firewood and took classes at Three Rivers Junior College. He and his wife also worked for the mail train when the family lived near Hunter.

“They would have to have it sorted by the time they came to the next town,” says Blaylock Wallace. “The train didn’t stop in the small towns. They would just throw the bag out for someone to pick up. If there was outgoing mail, it would be retrieved with a long hook from a pole along the side of the track. This had to be timed correctly. Sometimes they would miss the bag and have to wait till the next time they came through.”

Perhaps due to a combination of stress and genetics, Billy Blaylock’s life was relatively short.

“He had his first heart attack when he was 36,” says Blaylock Wallace of her father, who died when he was just 52.

By then, the family was living back in the Salem area. When Blaylock Wallace was in fifth grade, the family moved near Lenox, a tiny town near Salem and just a few miles from where she now lives. They relocated after her grandmother passed away and her father inherited a house.

“We moved back up, which was the worst for me. That was the worst move; leaving my friends and a river, and I just loved living down there,” she says. “I didn't like it here at all. But then I met my husband.”

Blaylock Wallace and her husband, Mike, wed in 1978. She was 17 years old — and one month post-high school graduation.

“I was just defiant for a hillbilly. I was going to graduate high school before I got married,” she says. “I started school early, and my birthday’s in July. So I got out of school when I was 17, got married, and turned 18 that July.”

Life growth and change

Blaylock Wallace quickly became a mother, a role that expanded to three children. She later worked as a cook at the local school, where her husband was a custodian and bus driver. They also farmed, an enterprise that brought them to their current home and herd of beef cattle.

And, about four years ago, it’s where she put a brush in her hand and began telling her story through paint.

She was always interested in the concept, but was discouraged from painting while in high school by a teacher who was primarily interested in the fine arts. There were a few projects here and there in the following years, but the approach of a life milestone led her to pursue the idea in earnest.

“When you turn 60, something happens to you. You’re just like, ‘Yeah. I’m going to do that,’” she says of feelings she experienced as her new decade approached.

After several family members died, it also gave her a way to express her feelings. Since then, sister Billie Jean Blaylock Boley has also entered the folk art world, largely creating whimsical chickens.

“Painting is really therapeutic,” says Blaylock Wallace. “I’ve lost my sister, my brother and my mom in the last three years. Some of them (paintings) I would put online in those times and people would like, ‘Oh my gosh, I can see your heart in that.’”

Most of her work is produced in a recliner in her living room, where she paints as she has time and inspiration hits. All her work is done in acrylic, which transforms into scenes from her life, but also memories she’s heard about from when her parents were young.

“The paintings, for some reason, have fallen into the period of when my dad and mom are born, which is the late '30s,” she says. “I find just so fascinating how life has changed since they were young. And they went through the end of the Depression, the wars, and so it gives me a lot of fodder for what I do.”

That said, those ideas aren’t the result of significant brainstorming.

“I don’t want to say I have visions in a weird kind of way, but I usually hold the canvases in my lap and pray over them that they’ll be inspired,” she says. “Then I just start painting and sometimes at night, I’ll think, ‘Oh my gosh’ and I’ll remember something that meant a lot to me when I was a kid and I just can’t wait to get it down, and so I’ll paint for like two days.”

In the years since she’s produced about 400 paintings and sold the vast majority of them. Some are at galleries — from down the road in Licking at the Texas County Museum of Art & History to the Visionary Folk Art Gallery in Dayton, Ohio — and others are sold over the internet. She’s gotten notice and encouragement, too, from others in the folk art world.

“I got connected with some really neat people online, and one of the guys started up a folk art aid and people started picking up (my work),” she says, who since her start has also illustrated children’s books, one of which has yet to be published. “It was so exciting because I’d never sold a painting in my life. And it was just so exciting to be validated. Up to that point, I was just kind of Mom and Grandma.

“I’ve made so many friends. I pack up paintings and send them off, trusting that some money will come back in the mail at some point — and it always does. I don’t do pay apps or anything like that. And so in doing that, I’ve corresponded with people from all over, and some up in Canada. And I’ve saved every piece of correspondence.”

Even greater personal connections

While the eyes that see her paintings may feel emotion, they might not know the specific people who inspired the scenes. A clearer link is the initials in the corner: CBW. Keeping her maiden name part of the work is important to Blaylock Wallace, given that the name was also important to her father.

“My Uncle Alan was killed in war — Korea — and Daddy took it hard,” says Blaylock Wallace, who says that just four of the 14 children were boys, and not all of them had sons. “Daddy wound up with all these girls. We were joking one day, and it's like when I was born, I can hear my dad saying, ‘Joyce, you're not even trying.’ He was shooting for a ball team, and then he had to teach us girls to play ball.

“It’s not a liberation type thing in my mind,” she says of using both names on her work. “It’s just that Daddy wanted the name to go on, and so much of what I do is based on him and Mother, and I just feel like it’s real important.”

Something else that is important to her is keeping her work accessible at a price point most can afford. The majority of her paintings currently sell for about $50.

“I figure if you stay home and don't eat out two times, you can afford one,” she says. “And that's how I'd love to keep it.”

Outside her home, there’s a small building set across the grass. Inside it is a bed and space where her grandchildren and friends come to stay, and it’s decorated with her life. Or more accurately, paintings she’s created that tell its story.

“My life is not all sunshine and roses,” she says. “I’ve had setbacks. But if you don’t have joy, you don’t have anything. Keeping your joy in the midst of the deep sorrows — it’s hard sometimes. But you’ve got to live life.”

With sunlight streaming through a window, she shares not a painting but a poem that speaks to that reality and was inspired by a family tragedy. She begins to read:

If these old Ozark hills could sing, what kind of song would they sing?

A joyous one of the smallest baby hummingbird or the tallest proudest tree

Of babbling creeks or rolling rivers?

Of beautiful hill children’s “playing in the rain” shivers?

Of trout and sunfish and goggle eye and chub

Of a farmer’s muck boots stuck in the mud?

Of the beckoning of a church bell’s ring

Or a new baby calf in spring?

If these old Ozark hills would sing, what kind of a song would they sing?

A mournful one of a brave, slain warrior?

Or a dying soldier’s last request that he be laid beside his mother to rest?

Of the souls of the salt of the earth buried there

Or the mother buried by her baby’s graveside prayer?

If these old Ozark hills could sing, I think it would be a song of love

The love of the dark, rich earth

Of families and neighbors and God above

All the riches these old Ozark hills provide to the richest of us who within them reside

For you know, they never really belong to us

We only watch over them while we’re here

And most of us know how important it is to hold those memories dear

In these old Ozark hills

“That’s my life,” she says, speaking of moments of both joy and sorrow that fill its days. The words share of life’s ultimate beauty, but were prompted by the death of great-grandchild who remained part of the Ozarks.

“We brought the baby and he’s on the back hill on the back 40 of the farm,” she says. “Where I will lay someday.”

Click here to visit Folksy Paintings, Wallace Blaylock’s Facebook page that’s dedicated to her work.