The Ozark Empire Fair and the beginning of August are here. I link the two events.

Meteorologists from the National Weather Service (NWS) support emergency management for the fair, and a number of years ago they even had a booth there at the E-Plex. I was there many times. Hot weather often accompanies the fair, along with storms at times.

After the Ozarks Empire Fair, the Missouri State Fair will quickly follow and the National Weather Service provides support for that. The evolution of communicating weather information is part of the theme of this month’s column.

Many communities in southwest Missouri have flirted or passed 100 degrees at least once this summer. The Springfield-Branson National Airport weather station finally hit 100 degrees on Saturday, July 29, right before an outflow boundary from thunderstorms knocked the temperature down about 10 degrees, and then later a weak front brought a slightly cooler air mass into the area. Heat advisories and warnings have been common this past month.

All-in-all, the average temperature for Springfield (measured at the airport) for July has been less than one degree Fahrenheit above normal. Pretty typical. Rainfall has been spotty. While the airport has been drier than normal, some areas of Springfield saw flooding with more than four inches of rain on July 7.

Joplin has been hotter, passing 100 degrees several times. Drought continues to affect the region to some degree.

It doesn’t look like we are done with the 100-degree weather as we move into early August. Heat related illness can affect the young and old alike. A quick search of those vulnerable include:

- Athletes

- Laborers

- Military personnel

- Workers who wear protective clothing (e.g. firefighters)

- Workers in hot indoor environments with poor ventilation (e.g. kitchen or laundry workers)

- Older adults

- Infants and children

- Individuals with chronic health conditions

- Low-income individuals

- Pets

Cooling centers (map link and map with addresses and hours from the State of Missouri ) are made available for those who need relief from the heat.

A weather nerd’s life

When I look back at my childhood interest in weather and meteorology, I can’t help but marvel at how far computer technology has come. There was no internet, which seems almost unimaginable to younger people today.

My dad was a scientist, and my parents encouraged my unusually strong interest in meteorology. They bought me a “weather station” when I was a pre-teen, and that quickly graduated to more sophisticated equipment as I got a little older. Weather books — some probably a little advanced for my age — were on my shelf. I learned to observe the weather, watch trends, and yes, make some crude predictions based on those observations. I loved the big winter East Coast Nor’easter storms. Watching the barometer drop, the wind howl, and the snow pile up was a rush, and still is.

I’m starting to feel like an old man on a front porch.

“Well, back in my day we did things the hard way, AND WE LIKED IT!”

Nope. I can say truthfully that I like the way weather data and forecasts are more available and more accurate today compared to my youth of the 1970s. However, I do sometimes miss the “mystery” of the weather and weather forecast. There was a certain amount of art and science to meteorology back then and, of course, the completely missed Nor’easter that would dump a foot of snow.

It’s not that there aren’t meteorological mysteries today, but science is much further along than it was 50 years ago. Highly advanced computers make the data much more accessible to the masses through smartphones and the internet.

Early in my career, meteorological fundamentals highly stressed analysis of weather observations and manually extrapolating the observed conditions into the future with pattern recognition and some science based “rules of thumb.” Yes, computer models were available, but today’s smartphones have 5,000 times the computing power of the world’s most powerful supercomputers from the 1980s. Weather observation networks and computer generated weather forecast models were crude by today’s standards, so the art and skill of weather forecasting required a good understanding of the how’s and why’s of those fundamental rules of thumb.

Flash forward to today. Supercomputers are mind-blowing. The rules of thumb that were once manually applied to a weather situation have been computerized and categorized. It’s not a small wonder that artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being applied to weather forecasts, and I felt this was especially true as my operational meteorological career ended.

The shifting role of the meteorologist

I expect cloud computing and a more “hands-off approach” to day-to-day forecasting will continue to free up time to allow meteorologists to concentrate on communicating potential weather impacts and forecast uncertainty with partners, like offices of emergency management.

Don’t get me wrong. There is still a place for the trained meteorologist in weather forecasting. Small scale, hard to model weather phenomena such as severe thunderstorms and tornadoes, winter precipitation, and how weather affects wildfires will still need the forecast touch of a skilled meteorologist.

However, the roles are shifting toward different career paths. Meteorological programmers and scientists will continue to develop better science-based forecast techniques, and science communicators will work with weather sensitive partners and organizations to better prepare them for impactful weather.

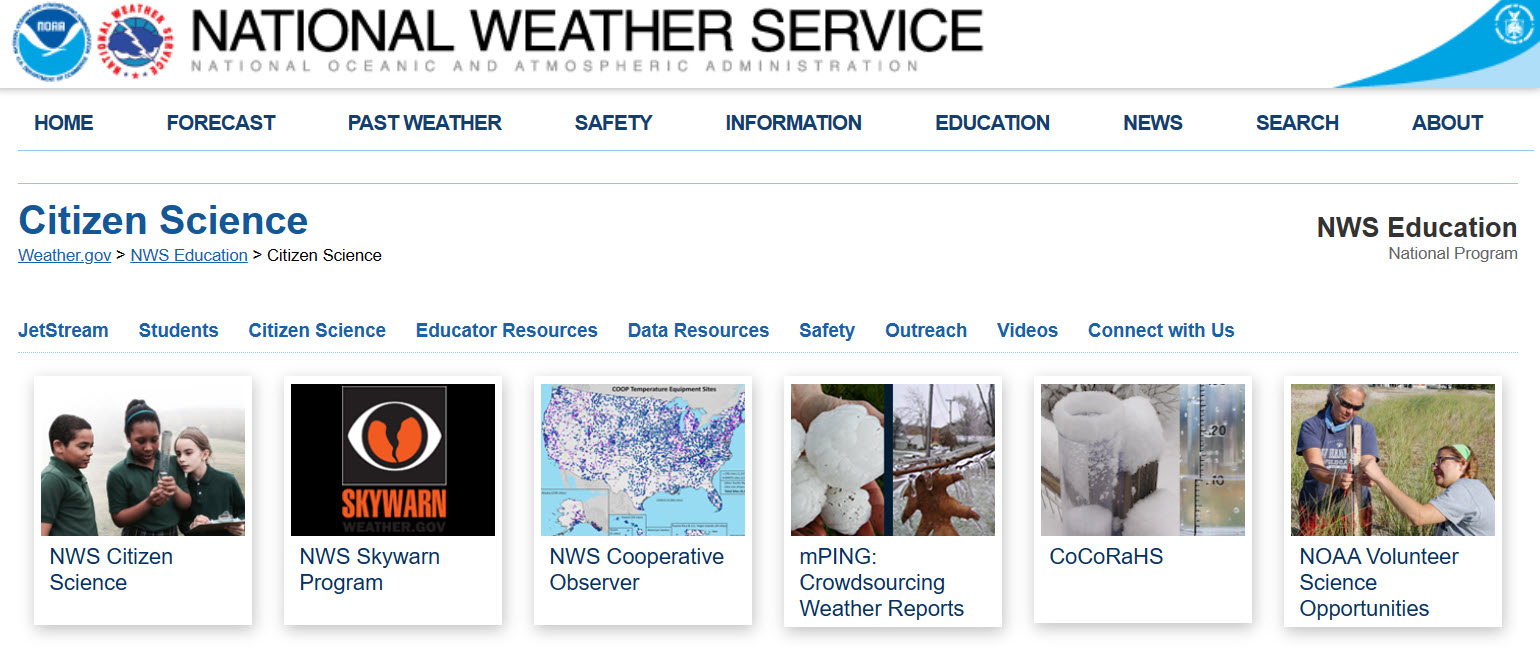

Communicating With Meteorologists Through Citizen Science

How appropriate! “Citizen” Science. OK, OK, not the Hauxeda.

If you are like I was a kid (or adult!) with an interest in weather, or you just want to help report severe weather, there are easy opportunities to contribute to citizen science weather observation networks.

Citizen science is a concept where the public voluntarily helps conduct scientific research. For meteorologists, communicating with citizen scientists such as storm spotters and weather observers help provide reports that can be critical to providing lifesaving storm warnings and help protect public and private property and infrastructure.

Tools For Weather Citizen Science:

Home weather stations: If you have an interest in gardening, farming, or want to integrate weather information into your smart home network, a weather station can be a good investment. They vary in price and quality. The old saying “You get what you pay for,” generally applies here. A web search for “home weather station reviews” should get you some good information.

Many stations can put their data online and a few can provide data in real time which can be very helpful to operational meteorologists.

mPING: Meteorological Phenomena Identification Near the Ground https://mping.nssl.noaa.gov/- is a project to collect weather information from the public. Data is collected through smart phones or mobile device in real time via a free, easy to use mobile app developed through a partnership between the National Severe Storms Lab (NSSL), the University of Oklahoma, and the Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies.

The data it provides can give meteorologists immediate feedback on thunderstorm impacts and winter weather precipitation types. Thomas Olsen, the NWS Springfield Observation Program Leader, states that mPING provides “ground truth of what is actually happening” and “helps meteorologists provide a timely warning.”

NWS Skywarn Program: Storm spotting training classes conducted by the National Weather Service and emergency management agencies can help you become familiar with the types of storm reports that are needed and how to report them. Classes are conducted in the late winter and early spring. More information can be found at the NWS Springfield website.

CoCoRaHS: Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network - https://www.cocorahs.org/

From the CoCoRaHS website: “CoCoRaHS (pronounced KO-ko-roz) is a grassroots volunteer network of backyard weather observers of all ages and backgrounds working together to measure and map precipitation (rain, hail and snow) in their local communities. By using low-cost measurement tools, stressing training and education, and utilizing an interactive website, our aim is to provide the highest quality data for natural resource, education and research applications.”

Celebrating its 25th anniversary this year, CoCoRaHS provides valuable data to a variety of partners. Thomas Olsen with the National Weather Service who is also one of the region’s program coordinators for CoCoRaHS says, “CoCoRaHS is used by local forecasts offices to assist in determining flooding potential. The rainfall totals are also by the regional River Forecast Centers for input into flood [computer] models.”

All you need is a rain gauge to send one-day rainfall totals in the morning. After you set up a free account, data can then be sent through the CoCoRaHS website or smartphone app. Some schools make this an ongoing project to help teach about weather and the environment.

Bonus 1950s Video: For those who made it this far, watch the first few minutes of this video to see a glimpse of meteorology from the 1950s from this Missouri State University Libraries’ YouTube video “Careers in Science (1953).” The entire video is a glimpse of the science and culture of the past.