Rose Jones, 80, opens the 2 and 1/2-inch-thick blue binder and I see the face of the young aviator.

He is movie-star handsome, self-assured, a Rock of Gibraltar jaw. His mouth is closed, yet you know he's smiling. The photo is of Virgil Thomas.

Thomas looks like someone who in 1919 was willing to fly 2,700 miles in an open-air-cockpit plane from San Francisco, over the Rockies, to New York, with railroad tracks as the main navigational tool.

It had never been done, and yet there was no shortage of undaunted, daring fliers willing to try. If that task wasn't difficult enough, the distance was doubled just before takeoff; it suddenly became a “there-and-back.”

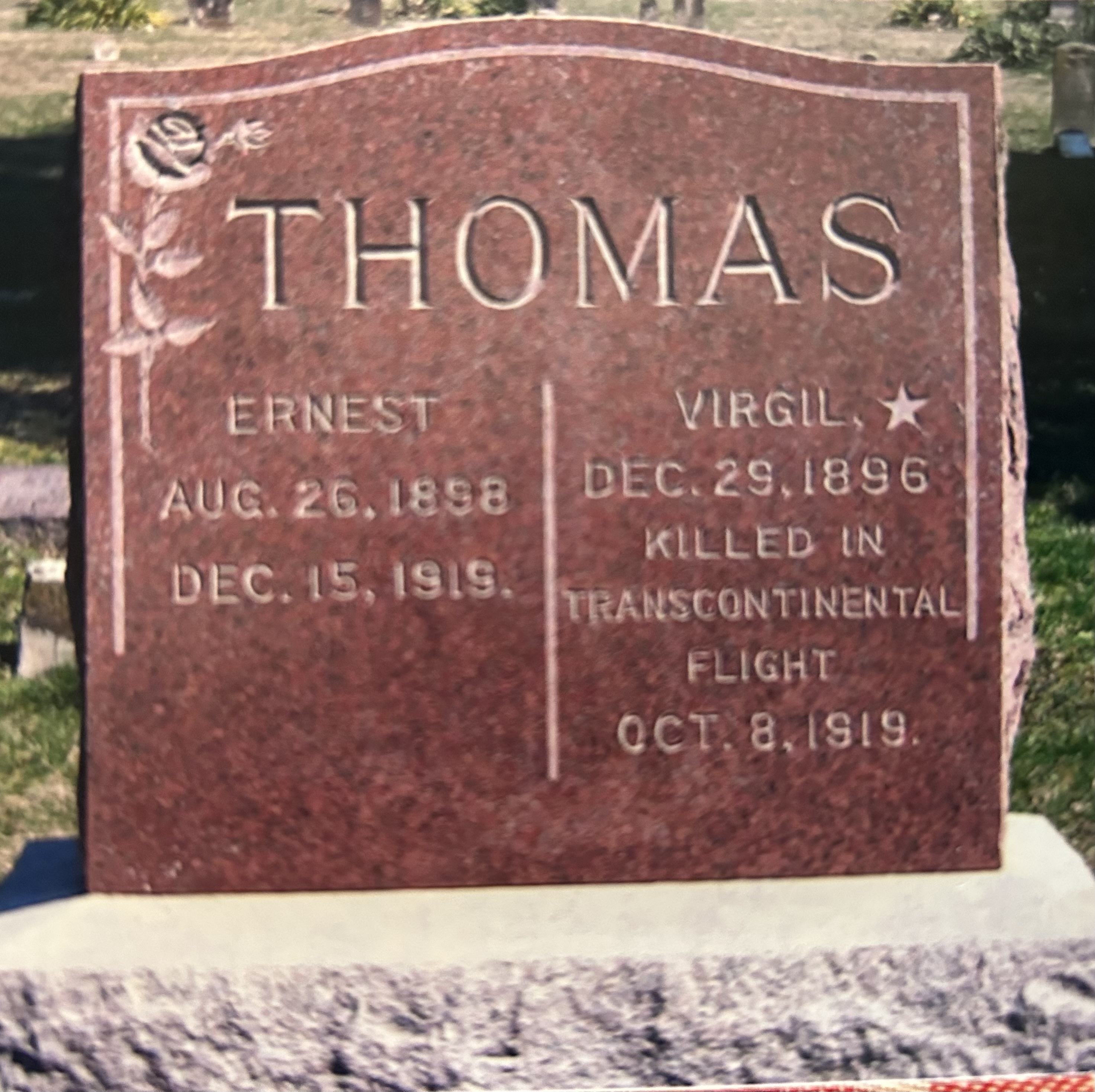

Thomas was born in Willard. He died forever young at 22. His biplane crashed in Salt Lake City during the race on Oct. 9, 1919.

He was not the only aviator to die in the race. The man in the plane with him died, too, as did five others.

Of the 61 planes that started, only eight finished the round trip. Seven men died, not counting two pilots who perished while flying to the starting point of the race on Long Island.

All but one of the race pilots were military aviators. Forty-six flew west from Long Island to San Francisco. Fifteen raced in the other direction, from San Francisco to New York, that first day.

Many of the planes crashed in foul weather.

According to a story in the Modesto (California) Morning Herald, those in one plane, “were compelled to withdraw from the race when their plane burst into flames and was forced to land at Canadice, New York.”

The binder was a surprise Christmas gift

It was Jones, who lives just outside of Springfield city limits in Greene County, who pieced together the blue binder.

“I am just a history buff,” she says.

Most of the photos, documents and memorabilia — including the wristwatch Thomas wore when he died — had for years been in the possession of Rose Jones and her husband, Paul.

She presented the binder to Paul as a surprise Christmas gift in 2015. He was grateful.

The familial connection is that Virgil Thomas was Paul Jones' uncle.

Paul Jones died at 79 in 2018 from leukemia.

Thomas was not the pilot; he was co-pilot

Thomas was too young to serve in World War I. He enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1918. The Armistice was signed Nov. 11, 1918.

He had flown in the United States to map mail routes and to watch for forest fires.

Thomas was the co-pilot of the biplane that crashed and killed both occupants on Oct. 8, 1919.

The pilot was Major Dana H. Crissy, 30. In the early 1900s, Crissy was an artilleryman at the Presidio military base in San Francisco. He dreamed of flying airplanes and, ironically, wanted to prove to the world that air travel was effective, reliable and safe.

After Crissy's death, the air field at the Presidio was named after him.

The field has been shut down and the Presidio Army base became a national park in 1994. A green space is still called Crissy Field.

The park is beautiful. I was on Crissy Field when visiting San Francisco in May 2023, having no idea at the time who Crissy was.

The race grabbed newspaper headlines

In typical garbled government-ese, the event was called the “Army's First Transcontinental Reliability and Endurance Test.”

The pioneering flyboys and just about everyone else called it a race.

It was the idea of Brig. Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell, a hero of the Great War and the man considered the father of the United States Air Force, created in 1947.

Mitchell had seen how vital air power was in World War I, and how ill-prepared the United States was for fighting from the sky. He foresaw how important air power would be in future conflicts and was concerned when he saw that once the war ended, government and private industry quickly lost interest in making airplanes.

For Mitchell, the idea of the race was to focus the nation on aviation and its unlimited potential.

The race did that. It grabbed newspaper headlines. Back then, newspapers were all there was when it came to mass communications.

Large crowds cheered the aviators at the 20 refueling stops along the route.

Readers could follow the exploits of Lt. Belvin Maynard, an ordained Baptist minister from North Carolina who flew with a German police dog, Trixie. The dog shared the rear cockpit with an airplane mechanic.

The New York Times ran 30 stories on the contest, eight on the front page.

A letter to Mom the day before he would die

In the blue binder are personal letters Thomas wrote to his family — including one to his mother on Oct. 7, the day before the race:

“‘We're off' or practically so, we leave at 6 a.m. tomorrow. Here's a go at last. Hope we get there alright. Hope to be some where in Nebraska this time tomorrow. Will drop you a line from where ever I am at. Wish me lots of luck for I want to get there.

“... Every thing is fine and dandy for our start from here tomorrow morning. We have a dandy ship and a good chance to make a second across.

“You can keep track pretty easily in the papers at least the Frisco papers. Well don't worry and ‘Watch our Dust.'”

Virgil

According to family history, Rose Jones tells me, Thomas's father, William Clarence Thomas, unintentionally learned of his son's death just that way — via a newspaper headline.

He was on his way to work in Needles, California, when he spotted a front-page story about the fatal crash. He read it.

Virgil Thomas and Crissy took off in California and had safely reached the Buena Vista landing field at Salt Lake City, the first overnight stop in the race. They were the ninth eastbound arrival.

Then, tragedy struck, according to a news story in the Modesto Morning Herald:

“As the huge machine approached the field Major Crissy was seen to signal a greeting to his brother aviators who had preceded him. He started to circle the field preparatory to landing.

“As he was completing the circle Sergeant Thomas was seen to stand up in the observer's cockpit and he too waved to those on the field.

“With the engine shut off the machine had started to run into the straightaway before descending when it suddenly turned and dived, nose down, 150 feet into the pond of mud and water.”

Crissy apparently had turned too quickly, going into a nose dive.

Thomas and Crissy were pulled from the wreckage, unconscious, and were dead before they arrived at a hospital.

Crissy had a wife and two small daughters. Thomas was single.

Body brought back to Missouri

Virgil Thomas's father accompanied the body back to Missouri, where the burial took place at Mt. Pleasant Cemetery.

During the funeral, pilot Ralph Adel Snavely, then a lieutenant, flew overhead and dropped flowers. Snavely, born in Aurora, would go on to become a brigadier general.

The Thomas family moved back to Missouri.

Two months after Virgil died, another son, Ernest Thomas, passed away in December from health complications. He is buried next to Virgil.

Some concluded that the air race across America — and back — was reckless and showed not only Mitchell's enthusiasm for aviation but also his arrogance.

The Chicago Tribune accused the Air Service of “rank stupidity.”

In a wonderful story from Nov. 13, 2022, that appeared in Politico, writer John Lancaster points out that the race did, in fact, show Americans what an air transportation system would actually look like.

The piece was headlined: “The Hare-Brained, Deadly Stunt that Helped Launch America as an Air Power.”

Lancaster is the author of “The Great Air Race: Glory, Tragedy, and Dawn of American Aviation.”

This is Pokin Around column No. 134.