Our society asks a lot of jurors. But seldom do we ask how they're doing after an horrific trial with gruesome evidence.

In mid-December, Meredith Stidham, 35, was a juror for the first time in her life. It was a Springfield murder case involving Crystal M. Dye, 41, who was beaten and strangled to death earlier in 2023.

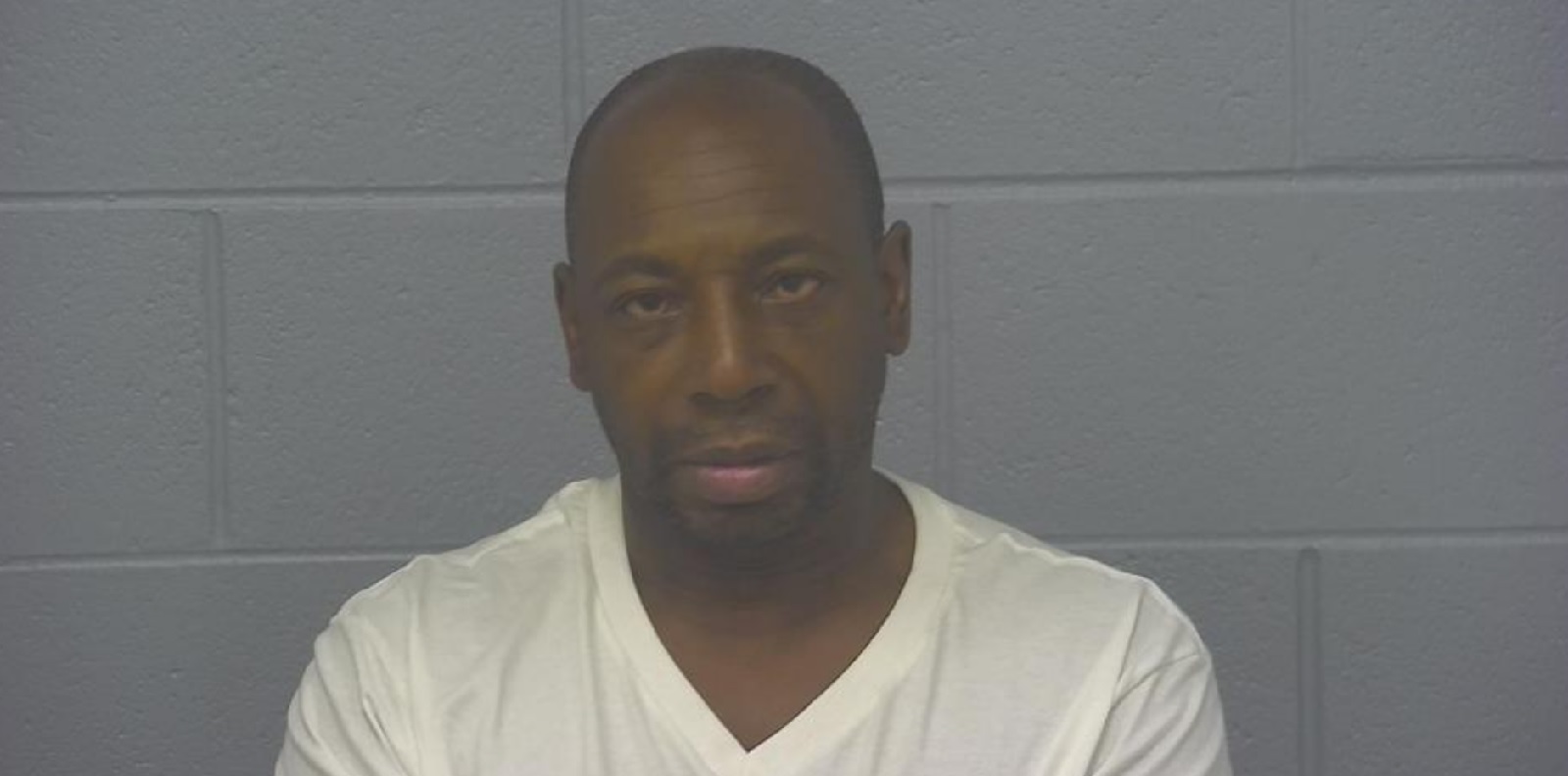

Jerome Poole, 60, was the defendant. He has an extensive criminal record and did not testify at his trial. He was convicted Dec. 13. Colleague Jackie Rehwald covered it for the Hauxeda.

During the trial, Stidham and other jurors were instructed to look at big-screen images of color autopsy photos.

One showed Dye's scalp pulled back in a flap, revealing 13 bruises on her inner scalp that otherwise would not have been visible to investigators. The bruises were created by an unknown blunt-force weapon.

“I remember I was sweating a lot,” Stidham tells me. “My heart was racing. It was hard to look and I found myself looking and then just looking away and I thought, ‘Well, I've seen what they asked me to look at and I'm not gonna sit here and just stare at it.'”

She avoids crime dramas, horror movies and gore

Stidham grew up in Springfield. She attended high school at Grace Classical Academy on East Cherry Street. Her maiden name is Frazier. She lives in Greene County just beyond city limits. She works in sales for Date Lady on West Commercial Street.

She has spent her lifetime avoiding gruesome images. She does not watch true crime dramas. She does not watch horror movies.

“I avoid that kind of thing,” she says.

“I remember seeing one picture of a cadaver when I was a kid because my dad worked on a cadaver. He's an emergency room doctor.”

Another gruesome autopsy photo showed the victim's bulging eyes, fixed wide open with a retractor to show the burst blood vessels in her eye balls — an indication Dye was strangled, which was the cause of death.

In that same photo, Stidham says, the lower lip was stretched down to show yet another large bruise, this one inside her mouth. The photo also reveals that Dye, a long-time drug user, had few teeth left.

It's jurors who do the heavy lifting in our system

Nevertheless, Stidham did her job. She looked at images she would have rather not seen and listened to testimony she would have rather not heard. She paid attention.

From Day 1 in this nation, those accused of a crime are entitled to a trial in which they can be judged by a jury of their peers. It's in the Constitution, and was part of the Bill of Rights.

In my view, it is jurors who do the heavy lifting in our system. They are called in as our ultimate arbiters of justice. They are neither specialists nor exuberant participants. They are our neighbors.

If they fail at their duty, everything else falls apart. They deserve our appreciation and I'm happy to report that the Missouri Bar hosts Juror Appreciation Week every May.

An alternate juror, not part of deliberations

A criminal-case jury consists of 12 people and two alternate jurors. The judge dismisses the alternates after all the evidence is heard and the lawyers have finished their closing arguments. Alternate jurors do not participate in jury deliberations.

Stidham was an alternate juror. After her dismissal, she and the other alternate juror stayed. They stuck around in the courtroom and waited for the verdict.

“I was so invested,” she says.

While the jury deliberated, defense lawyers asked her what she thought.

She told them she thought their client, the defendant, was guilty.

They didn't seem surprised, she says.

The bailiff asked her what she thought.

She told him the same.

What was behind request to look at body-cam video again?

One thing puzzled her as an observer in the courtroom. She wondered why the jurors in deliberations had asked the judge if they could once again look at the body-cam video from the first officer at the scene.

Poole had called 9-1-1, but apparently only after he had killed Dye.

Greene County Circuit Judge Kaiti Greenwade agreed to let the jurors watch it again.

Stidham wondered why jurors needed to see it; what were they looking for?

“I wondered when they asked for that,” she says. “I was thinking maybe they just asked for that to — I don't know — show that they're really working on things.”

All potential jurors were told during selection that it was a murder case and that the evidence included horrific autopsy photos.

A couple potential jurors asked to be excluded because of that and they were.

Looking back, Stidham says, she is not haunted by the images. Not at all. She slept well, even during the two-day trial. She is unscathed and enjoyed her service.

“I felt like it was a little bit of an education for me,” she says. “It was kind of like sitting through a forensic science class. I feel like I was able to look at things objectively and not get emotionally involved — even though it was a woman who wasn't that much older than me who was strangled to death. And abused.

“It was like I was sitting in a class collecting all the evidence, thinking through all the things to make a decision to come up with what I personally thought ... It wasn't dramatized, there was no music. It really was not, at least for me, an emotional kind of roller coaster.”

She wondered ‘why?' What was motive?

She was convinced Poole killed Dye, but wondered why. What was the motive?

“Why would this man want to strangle this woman? But we didn't get a lot of backstory.”

A motive was never provided. In fact, Poole told police he didn't even know Dye's name.

On reflection, Stidham says, it was frustrating to not participate in deliberations.

“I feel like I got cut off right at the end,” she says.

But her dismissal as an alternate allowed her to sit in the courtroom and observe something jurors in deliberations could not.

While waiting for a verdict, which did not take long, the judge took off her robe and sat in the courtroom and the lawyers — prosecutors and defense lawyers who had been antagonists — chatted amiably.

“It was almost like we had been watching a play. And the play was over. And they were just all off stage. It was really strange to me. But again, this was a new experience. I didn't realize that it would be like, oh, all these attorneys know each other and they hang out. ... It didn't matter that a few minutes ago they were pleading with us to choose their side.”

Poole is scheduled to be sentenced at 1:30 p.m. March 8.

This is Pokin Around column No. 152.