Every little bit helps, but number crunching over housing and homelessness left some members of the Springfield City Council searching for hope.

Springfield stands to receive about $3.8 million to combat homelessness as part of a City Council bill up for final approval June 27. The American Rescue Plan Act contained $5 billion for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Home Investment Partnership program.

In Springfield, about $2.2 million will go to shelter housing development, and another $1 million will go to rental housing development.

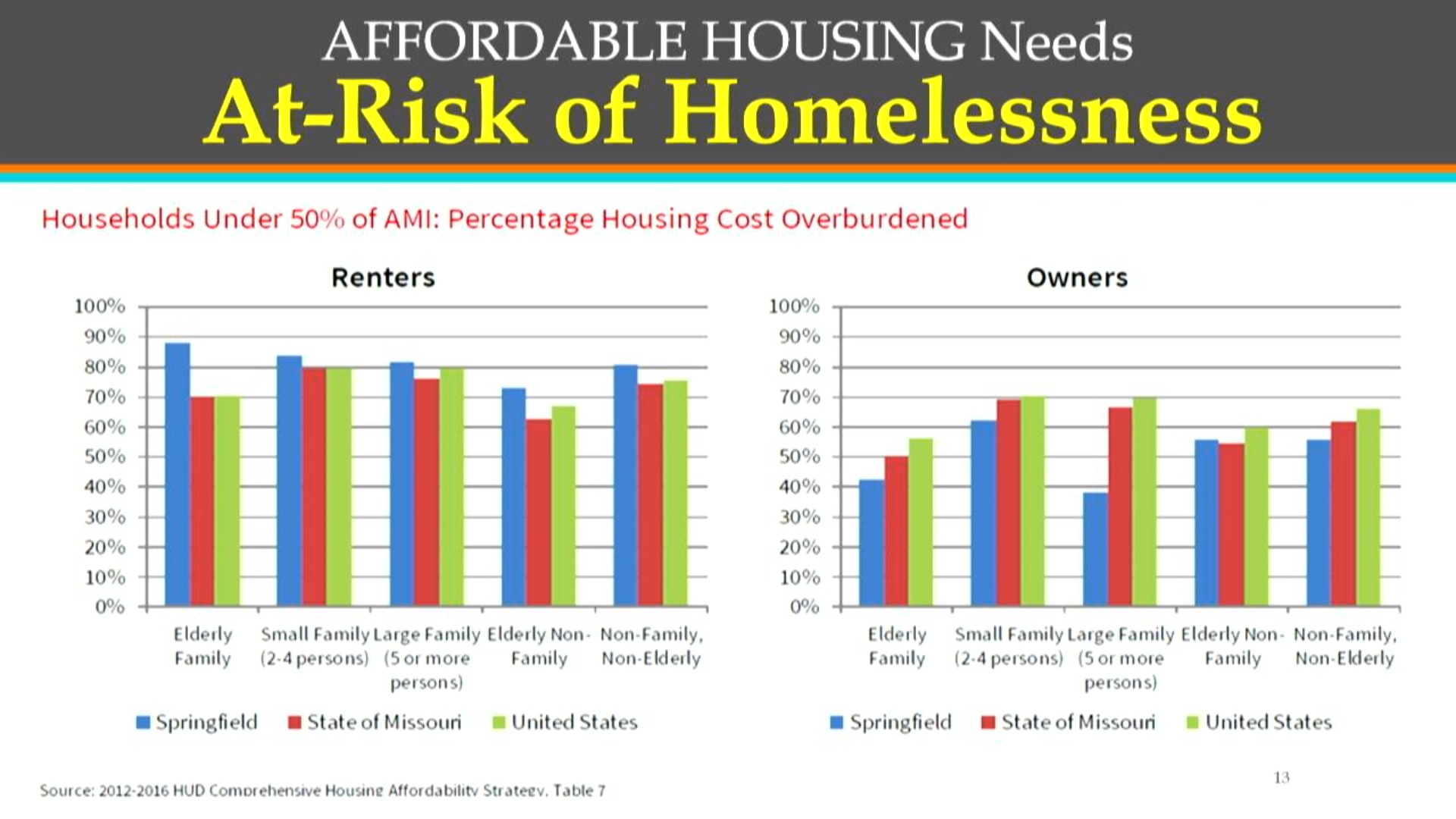

People living in 8,230 Springfield households are estimated to be at risk of homelessness, because they don’t earn at least $2,536.67 per month, or $30,440.04 per year. That’s the minimum amount of household earnings it takes to contribute less than 30 percent of a household income to the average cost of rent in Springfield, which is $761 per month, according to data shared with the City Council. Households above that threshold are generally considered to be more unstable and at the highest risks for homelessness.

“So we’ve probably got a lot of people on the verge of homelessness then,” said City Councilman Craig Hosmer, the bill sponsor.

With multiple people in some households, it’s at least 13,000 people, and maybe more.

Springfield’s HUD office received a grant for $3,805,703. Bob Jones, grant administrator of the Springfield Planning Department, explained to the City Council that HUD must account for the money’s use in specific ways.

“The grant process was very unusual,” Jones said. “They gave us the grant first, which council approved last November, but they require us to develop an allocation plan for their approval based on data and consultation with various homeless-providing agencies. Then, after we get that approval, we can implement the grant based on their allocation plan.”

Jones said the limits of the HUD instructions made it difficult to determine what activities the grant could fund, but it spelled out a great deal of work that the money would not pay for.

“HUD guidance was very extensive,” Jones said. “Funding can only be used for certain defined beneficiaries called ‘qualifying populations,’ that is the homeless, those at risk of homelessness, those fleeing or attempting to flee domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, stalking or human trafficking, or others requiring assistance to prevent homelessness or those at great risk of housing instability.”

Story continues below:

The HOME-ARP grant will put $3.2 million toward what is estimated to be about a $1.2 billion issue in Springfield.

“That gives you an idea of the magnitude of the issue,” City Manager Jason Gage said. “As you know, we don’t handle that kind of money and we can’t get that level of money from the federal government because there is a deficit in many, many places throughout the country.”

Unsheltered persons have a hard time moving from the streets to stable housing because of shortages at each stage of the process. Many emergency shelters have limits on the number of days that a person can stay there. Sheltering agencies also work to help homeless people find jobs or otherwise take steps to earn a stable income.

“We feel like this allocation of funds will address the two bottlenecks in that continuum of care as they climb the ladder in life’s trajectory,” Jones said.

Researching homelessness and sheltering

City staff members partnered with the Ozarks Alliance to End Homlessness to gather information on agencies serving unsheltered persons.

“No one agency can do this whole thing. It involves a lot of independent agencies, a lot of churches and faith-based organizations are actually supporting homeless folks as we speak, and they’re not participating in the HUD projects, so we didn’t have exact data from most of them,” Jones said.

Jones said he and the other city employees involved in the project made contact with 109 people from 20 different agencies dedicated to helping unsheltered persons.

“We asked them to pick the top two of the eligible activities that they would prefer we fund,” Jones said.

“Non-congregate sheltering,” is the term HUD uses to describe emergency sheltering, which occurs when homeless persons are temporarily placed in hotel rooms, apartments or houses on a short-term basis.

In Springfield, HUD typically moves qualified applicants from shelters into transitional housing. The houses are typically small, three-bedroom, two-bathroom houses. The waiting time for a housing voucher is usually long. It is sometimes referred to as “Section 8 housing.”

Jones said the cost to build low-income houses in Springfield is climbing.

“We used to do them for $135,000, now it’s over $200,000 to build a three-bedroom house,” Jones said. “Even the HUD grant money is not sufficient enough to develop 8,000 of them. It’s going to be a major effort and we’re fighting the same odds that everybody else has talked about tonight.”

Story continues below:

$2 million to build 10 houses

To qualify for low income housing, a person or family’s household income must be less than 30 percent of the median household income for the Springfield metropolitan area. General Councilwoman Heather Hardinger was unhappy to learn that the money Springfield will receive from the HOME-ARP grant would cover the construction costs for about 10 houses.

“You said 8,000 (households at risk) is conservative, and it could be even double that,” Hardinger said. “In my opinion, I think that we need to be diligent about this in thinking about the creative ways that we can make housing more affordable for folks in Springfield.”

A shortage of affordable housing coupled with rising rates to rent makes it difficult for the person in transition to save enough money for first and last month’s rent on an apartment or house.

“Rental vacancies are next to nothing right now; there’s waiting lists just about everywhere,” Jones said. “All you have to do is tell your neighbor that you have a house for rent and it’s occupied shortly, so the competition is tough.”

Jones said it’s estimated that only about 3,000 rental units in Springfield have rates affordable for persons living at 30 percent or less than Springfield’s median household income.

“Currently, there’s a lot of money on the street for rental assistance right now,” Jones said.

The state of Missouri helped 988 Greene County households through a rental assistance program called State Assistance for Housing Relief. Greene County also received $18 million in relief funds, and Jones said it has about $5.7 million remaining.

Story continues below:

Issue with data use

General Councilman Andrew Lear referred to a meeting the City Council held with advocates for the unsheltered in the spring of 2022. Lear said the federal government’s use of the point-in-time count, a yearly census of homelessness across the nationally-conducted on a single night in January, doesn’t give a true representation of homelessness or the homeless population.

“I know that HUD requires point-in-time data, that’s what you’ve got in your report,” Lear said. “We also know that particularly, maybe, the ‘21 point-in-time survey, I think, severely undercounts what is out there on the street today. The last number I saw was somewhere around 1,300 folks.”

HUD uses the point-in-time census to collect and preserve historical data on homelessness across the United States. On Jan. 27, 2021, the point-in-time count for Springfield resulted in a count of 583 homeless persons, according to a report by the Ozarks Alliance to End Homelessness.

Connecting Grounds Pastor Christie Love, one of Springfield's leading advocates for the unsheltered community, pointed to a different set of data from the HUD data, a unique-to-Springfield survey that she calls the “street census.” The census is a collaboration among Springfield’s homeless outreach organizations and attempts to count Springfield’s unsheltered population on a weekly basis. As of 12:05 a.m. on March 28, 2022, the street census was 1,139 people. People are added to the list as they access services, and go off the list if they get into housing, move away from Springfield or die.

Lear wants Springfield residents to look beyond the point-in-time survey when they think about unsheltered friends and neighbors.

“While it is a HUD-mandated number you provide, I just don’t want the community to think that that’s what we have. I think we probably have double, at least double that number today,” Lear said.

Jones said the point-in-time survey doesn’t count cases where a family may double up in a house with another family, or with relatives. It also doesn’t count cases where people temporarily sleep in a car while they look for their next place to take shelter.