This story is published in partnership with Ozarks Alive, a cultural preservation project led by Kaitlyn McConnell.

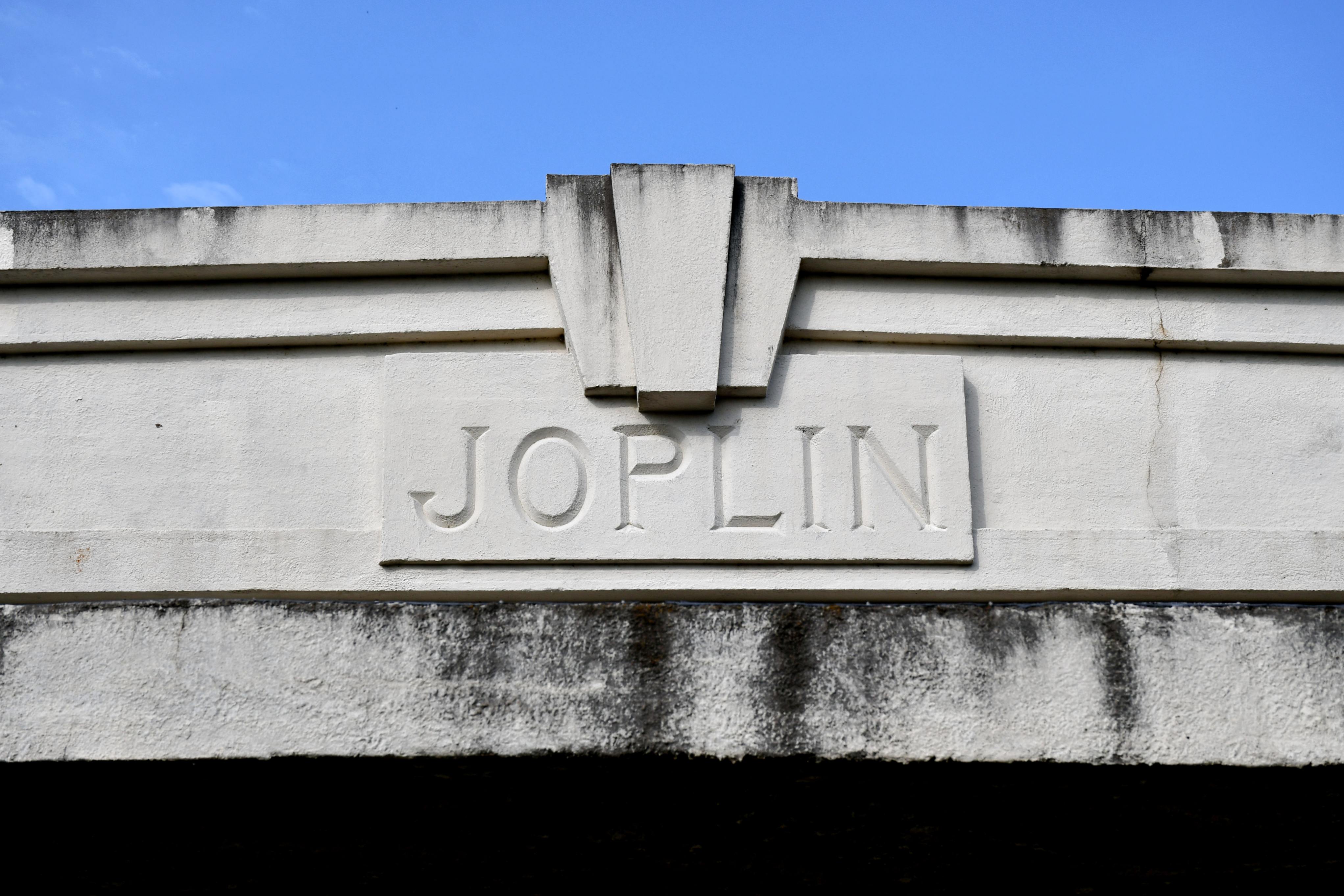

JOPLIN - The Joplin Union Depot is a survivor — as it hopefully will continue to be.

For more than a century, the stately white structure from the romanticized age of train travel has remained — through time, vandals, failed redevelopment and a tornado that took out parts of the rest of the town.

But like the trains that still trundle past on the active rail line, time doesn’t stand still. Deterioration has caused the depot to be a shell of its former self — and the focus of renewed effort to find it a new purpose.

Through its Endangered Properties Program, the Downtown Joplin Alliance announced a partnership in May with the Glenn Group to put the state-owned property on a national stage in hopes of finding a developer.

“It's just been sitting in our downtown vacant, deteriorating and deteriorating. And there’s never been any marketing done for it,” says Lori Haun, executive director of the Downtown Joplin Alliance, of the depot’s visibility on a broad scale. “And so, thinking about the idea of, ‘Oh, well, it's not developable’ — well, nobody's even tried really, because nobody knew it was there.”

What is the Joplin Union Depot?

The Joplin Union Depot, located northeast of the intersection of Main and Broadway streets, wasn’t the first depot Joplin had, nor the only one in town when it opened.

“Joplin had an expansive network of railroads,” says Joplin historian Chad Stebbins. “Joplin’s Union Depot served four railroads: the Kansas City Southern; the Missouri, Kansas and Texas, or Katy; the Santa Fe; and the Missouri and North Arkansas.”

It lived up to its name — the Joplin Union Depot — because its use was open to multiple railroads.

That fact was tied to contention in the city prior to its construction. In the early 20th century, local leaders — as well as those with the newly formed Joplin Depot Company — worked to recruit new railroad lines to the city, which was not appreciated by those already in operation.

The dispute was eventually resolved, and although access was given to all lines to use the station as wanted, not all did.

“The Frisco Building — still standing, being converted into luxury apartments — was a passenger depot for the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad,” says Stebbins, noting its operation continued through 1960.

According to an article in the Savannah Reporter newspaper, work began in April 1910, when “a force of 200 men began excavating the site for Joplin’s new $1,00,000 union depot.”

The facility opened in 1911, and was a cause for celebration, says information compiled by the Joplin Public Library:

“At 10:30 p.m. on June 30, 1911, two thousand excited spectators watched as the first train pulled into the million-dollar station. Fireworks, skyrockets, and torpedoes exploded overhead, and the train engineer responded by sounding his whistle loudly. The formal grand opening on July 20, 1911 attracted 5,000 citizens whose enthusiasm was hardly dampened by the drizzling rain. Beginning at 20th Street and proceeding down Main, a parade of police cars, fire trucks, marching bands, and thirty cars bearing railroad and city officials, arrived at the depot. The celebration and speeches continued for hours. Mayor Jesse F. Osborne approved the structure ‘composed almost entirely of waste mine gravel, moulded into beautifulness.’”

The depot was unique for a number of reasons, one of which appears to be making Springfield jealous. (So said the Springfield Daily Leader in 1910: “It would seem that Springfield should try to get the Missouri Pacific and Frisco to erect a fine union station here as will be done in Joplin. If the Frisco patches up its station here there will be no chance for a new one for ten or twenty years.”)

The Joplin depot's architect paid his rent in gold

One defining factor was who designed it: Louis Curtiss, a Canadian-born architect who eventually settled in Kansas City.

According to “Historic Missourians,” a project of the State Historical Society of Missouri, Curtiss had an impressive — and eccentric — reputation, including wearing all white and paying his rent in gold. Among his other successes, he began a relationship with the Santa Fe Railroad in 1905 that led him to design a number of depots across the country, and subsequently, time spent designing hotels and restaurants for the famed Fred Harvey Company.

“Louis Curtiss, an unconventional architect later renowned from coast to coast, designed more than two hundred structures during his thirty-five-year career,” noted the library’s information. “But it was the Joplin project that helped establish his reputation as a pioneer in fireproof concrete construction. He attracted considerable attention by utilizing local chat in the concrete mixture for the depot.”

The depot was also unusual in its day and time, and was considered to be “modern” railroad architecture, says its application for the National Register of Historic Places:

“This particular building, along with other concrete structures both in Kansas City and on America's western railroads, helped establish Curtiss' reputation as an innovative architect of the early modern period.”

The landmark featured two-story-high waiting rooms, restrooms, a ticket booth, telegraph office, and newsstand. A smoking room for men was also a feature, as was a ladies’ “retiring” room; the Rose Room restaurant, with capacity for more than 70 diners, and the Union Depot Coffee Shop, with a lunch counter that could serve over 50 customers.

The Joplin depot becomes vacant

The depot was used in various capacities until 1969, when the last train rolled away from the station.

Work quickly began to find a new purpose for the former depot. In 1972, just three years later, a newspaper article noted that the Joplin Centennial Committee recommended it be acquired and turned into a museum.

The museum apparently didn’t happen, but one element of the depot’s historical recognition preservation did: That year, it was nominated to the National Register for Historic Places and the designation was awarded in 1973.

Several other plans came and went in the following years in an effort to save the structure and use it for a new purpose. In 1985, a Springfield News-Leader article noted, a local woman named Nancy Allman purchased the property to preserve it, and with plans to restore it.

“I remember when it was the center of activity for the town,” she said in the article. “It was a tremendous gathering place.

“I was determined I wasn’t going to stand by and see another building torn down.”

Those plans ultimately did not work out either, and the Missouri Department of National Resources obtained the property through foreclosure in 1998. According to a 2010 article in The Joplin Globe, Allman was from whom it was acquired.

“With the highest and only bid of $175,000, the Department of Natural Resources was granted ownership of the building after unsuccessfully trying to sell it at auction,” noted another article, by Four States Homepage, in 2021.

Efforts to restore the structure

One person who has seen efforts to restore the structure multiple times is architect Allen Casey.

Formerly of Springfield, Casey led historical restoration projects during his career, and recalls being approached around five times for thoughts on the project over the years, one of which was with Allman.

“I don’t know how enthusiasm is for rehabbing the building now, but it’s generally been pretty strong,” says Casey, who has a personal interest in history and in recent years has led several other local restoration projects, including the Monett Historical Museum and the History Museum on the Square in Springfield.

Allman’s plan was one of two serious injuries he received regarding architectural ideas on depot redevelopment, he says. Another was from someone who was semi-interested, and two others were more casual. None, coming to him over a span of around 30 years, saw the project completed.

“I knew from everything I had seen that the city would be very helpful and the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) would be very helpful,” says Casey. “But it still takes a developer who is focused.”

He explains that it’s really a two-part project, and one that takes a big lift: Taking on a major restoration effort, but then also having a plan for it to make money in the end.

“I will say it will take a serious developer who really gets enthused about taking something like this on,” says Casey, “and has ideas about how to make it a financial success.”

In the 24 years since the DNR acquired the depot, proposals for the property from “financially capable purchasers” have been nonexistent, says Dr. Toni Prawl, Missouri’s SHPO director, an office that is part of the DNR. But there has been interest.

“Maybe it's just a phone call. Maybe they might follow up with a question in email, in writing, but then they don't necessarily go beyond that,” says Prawl. “Or at times, maybe there's just not any information about their financial capability. They don't necessarily demonstrate that they are financially capable of taking on a project like this.”

Prawl explains that the depot was acquired through its Historic Preservation Revolving Fund, for which authority is given to the DNR.

“That's a program that was established to help historic property that, at times, needed to benefit from a more sympathetic owner,” she says. “In many cases, properties that came to the revolving fund were threatened.”

The DNR ownership also resulted in the building being offered to the city of Joplin various times, Prawl says, but the offers were declined.

Visibility big issue for the Joplin Union Depot

Part of what both Prawl and Haun cite as an issue for the depot project is visibility. Given resource limitations, the DNR has not been in a position to actively promote the depot as an opportunity.

“There was, at one point in time, a revolving fund coordinator, and that position’s been vacant for years,” says Prawl, who notes that the office has limits on how its resources may be spent.

That is where Joplin’s Endangered Properties Program comes into play. Launched in 2020, the program works as an advocacy group to help cover expenses related to marketing historic properties in the area that are in danger.

“We realized a few years ago that we really need to kind of figure out better tools to be able to intervene in some of the vacant properties,” says Haun.

One might wonder if the tragic Joplin Tornado in 2011 — said to be the deadliest single tornado on record in the U.S. since official record-keeping began in 1950 — has made historical preservation even more of a priority in Joplin today than it was just little more than a decade ago.

“I think it did make us want to reinvest, and I think that's true across the board with people who stayed in Joplin after the tornado — we all chose to stay,” says Haun. “We all chose to reinvest and chose to improve the city. We realized that this was an opportunity for us to make a decision as to where we're going in the future.”

Such feelings led to the creation of the Joplin fund — separate from the state’s — that’s seeded by a $100,000 grant from the 1772 Foundation, which per its website “works to ensure the safe passage of our historic assets to future generations.”

That pool of money, Haun says, might be used for needs such as marketing, conducting a structural analysis, creating architectural renderings and more for at-risk historical properties. The first project it was able to help save was an apartment building, which was successfully redeveloped. In most cases, the money invested in the project would be recovered when it’s sold.

“Basically anything we need to do to answer questions about some of these historic buildings to try to move them forward,” she says.

“One of the easiest parallels would be the humane society. We’re the humane society for unwanted buildings,” continues Haun. “We're going to give you shots. We're going to give you a flea dip. We're going to brush your fur. We can't fix everything about you, but we're going to do what we can and then let people know that it's available.”

Looking forward

Through the renewed effort, DJA has partnered with the Glenn Group, a commercial real estate company in Joplin, to spread the word about the depot’s existence and availability to a much wider audience. And when — hopefully not if — there are inquiries about certain aspects of the building, Haun notes other ways that the fund may be able to help.

“One thing I’ve found in working in my position is I’ll walk people through some of these old buildings downtown and there’s always the same questions,” says Haun, giving a few examples. “‘What’s that crack in the wall? What about the lead paint? I wonder what it would cost to fix this? Does the roof leak?’ So if you can go in and you walk through the building and you’ve got answers to half of their questions, then you know immediately whether it’s going to be a good fit for them a lot of times. There’s still always going to be other things that have to be figured out, but it at least gets the conversation further down the road.”

No specific uses are in mind for the building, says Haun and Prawl, but they note that there is space for a lot of discussion and ideas.

“The way we're marketing it right now is just like, ‘Hey, we've got this thing. What do you think it should be?’” says Haun. “There's people who've done depot redevelopments all over the country, and we're kind of hoping that one of those people who've done something similar before sees it as like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is the perfect spot for this.’”

“There's not a price tag listed … because we want people to know that we are entertaining offers, and that everything is negotiable, and it's flexible,” says Prawl. “And we want to work with whoever is interested and has the ability to work with this property.”

Want to learn more?

Click here to learn more about the Joplin Union Depot property.

Resources:

“A union station,” Springfield Daily Leader, Feb. 13, 1910

“Breathing life into a shell,” Kathleen O’Dell, Springfield News-Leader, Dec. 13, 1987

“Historic Joplin Highlights: Union Depot’s legacy, controversy and attempts to save,” Four States Homepage, June 24, 2021

“Louis S. Curtiss,” Historic Missourians/State Historical Society of Missouri

“Joplin Council considers site for new library,” Springfield Leader & Press, Feb. 7, 1972

“Joplin’s depot difficulty,” Debby Woodin, The Joplin Globe, Sept. 5, 2010

“Joplin starts depot work,” Savannah Register,” April 15, 1910

Joplin Public Library information, no date

Joplin Union Depot, application for the National Register of Historic Places, 1972

“Plans to restore Joplin depot,” The Kansas City Star, March 20, 1977