IN-DEPTH |

The older boys held the twisting, 5½-foot snake. Black rat snakes are not venomous and not aggressive by nature, although being snatched by human hands can change a snake's disposition.

They were on a Boy Scout camping trip near Fellows Lake.

If you like snakes and want to study them, they advised 11-year-old Mike Crocker: you must first overcome the fear of being bitten, at least by non-venomous ones.

The boy offered his hand to the snake. The bite left puncture wounds; the bleeding soon stopped. The pain did not last long but the adventure has lasted a lifetime.

Crocker is longtime superintendent of Dickerson Park Zoo in north Springfield. He started at the zoo in 1976 and became superintendent in 1988. In that time, he has had eye surgery after being poked by a great blue heron, witnessed a co-worker tossed by an elephant, been squeezed by a python and was there the day a tiger escaped. His saddest day was when a keeper was killed by an elephant.

Crocker, 73, has retirement in sight.

Jumps off boat into a swarm of snakes

Crocker, when he was in his mid-20s, was in a boat in a cove on Table Rock Lake. He was fishing with lifelong pal Larry Davis. They had first met as boys at Bingham Elementary School.

“There were a bunch of water snakes, not water moccasins. The cove was teeming with snakes. They were thrashing around, spawning,” Davis recalls.

Water snakes are not venomous.

“And Mike just jumped off the boat right into the middle of them in waist-deep water. They were biting him and he had blood on his arms.”

Davis can't say he was completely surprised when Crocker abandoned ship. For years, Davis had gone snake hunting with him.

Teenagers cruising for snakes

They started back in elementary school and continued as students at Glendale High. Once they could drive, they would hop in Crocker's VW Bug and go 30 miles to Chadwick in Christian County, near the Mark Twain National Forest.

They mostly looked for pigmy rattle snakes, timber rattle snacks and copperheads.

Chadwick was loaded with them because of its proximity to the forest and because the roads had little snake-killing traffic.

“After the sun goes down, the snakes liked to lay out there on the warm asphalt,” Crocker recalled.

The teenagers would pin the snake heads down with hockey sticks that Crocker had altered for that purpose. They would pick them up, study them, maybe bring one home.

While other high-school boys cruised Kearney Street in tricked-out hotrods, preening for the girls — Crocker and Davis were drawn, instead, to the moonlit, snake-filled byways of Chadwick.

“Yeah, that is kind of weird, isn't it?” Davis said.

Heron that struck him in the eye

(From “True Tales from Dickerson Park Zoo,” 2021, by Mike Crocker)

In the late '70s or early '80s, the zoo had a great blue heron. One day, the keeper was holding it and as I approached I noticed she did not have the beak restrained. I was at eye level with the bird, and it lunged at me.

It hit me in the eye with its pointed beak and the pain dropped me to my knees. Blood ran out of my eye.

Someone took me to the emergency room at Cox North. By coincidence, an eye specialist was in the hospital. He gave me an injection in my eye to deaden the pain and then sutured the wound.

It healed; the sutures were removed; and today there is no evidence my eye was ever injured.

‘Going to pay me to do my hobby!'

Crocker has a nickname and you probably can guess it.

“Snake” was born in Springfield, the oldest of four boys. He attended McGregor and Bingham elementary schools and was in the first graduating class at Glendale High in which students attended all four years. He graduated in 1967.

He went on to Southwest Missouri State, now Missouri State University, and graduated in 1971 with what was then a new major — wildlife conservation.

He was hired by the zoo in July 1976 as a reptile keeper, where he was overseer of turtles, lizards and, of course, snakes.

His reaction when he got the job?

“Oh my gosh! They are going to pay me to do my hobby!”

To enjoy retirement, best not wait too long

After several promotions, he became Dickerson Park superintendent in 1988 when then-superintendent Dale Tuttle left to head Jacksonville Zoo and Gardens in Florida.

Crocker's adventurous career is in its final lap. He will retire from the zoo in late 2023 or early 2024.

“It's time,” he said. “My wife has been retired four or five years. Age is clearly catching up to me, too. I am tired all the time. I don't now have the energy I used to have.

“If I am going to have time to enjoy retirement, I need to do it while I am physically able to do it.”

He is scheduling his departure so he will not miss the zoo's 100th anniversary in 2023. In addition, the zoo next year will go through the re-accreditation process with the Association of Zoos & Aquariums. This happens every five years.

Snoopy, the poop-throwing baboon

(From “True Tales from Dickerson Park Zoo,” 2021, by Mike Crocker)

The zoo had a baboon named Snoopy. Like all male baboons, he was the dominant animal in his group, which consisted of himself and two females.

Snoopy had a peculiar quirk. He didn't like women with light-colored hair. Snoopy would throw monkey poop at them and he possessed a certain degree of skill in doing so. This brought him notoriety and guests would sometimes purposely antagonize him to get him to throw poop.

On one occasion he threw into a woman's mouth. On another occasion he threw it all over a woman's nice white winter coat. The woman was angry and wanted the zoo to pay to have her coat cleaned, which we did not do.

What really enraged him was when a man and woman embraced, or even kissed in front of him — particularly if the woman had light-colored hair. These innocent embraces were pretty much guaranteed to send him into a rage of poop throwing.

Crocker at home

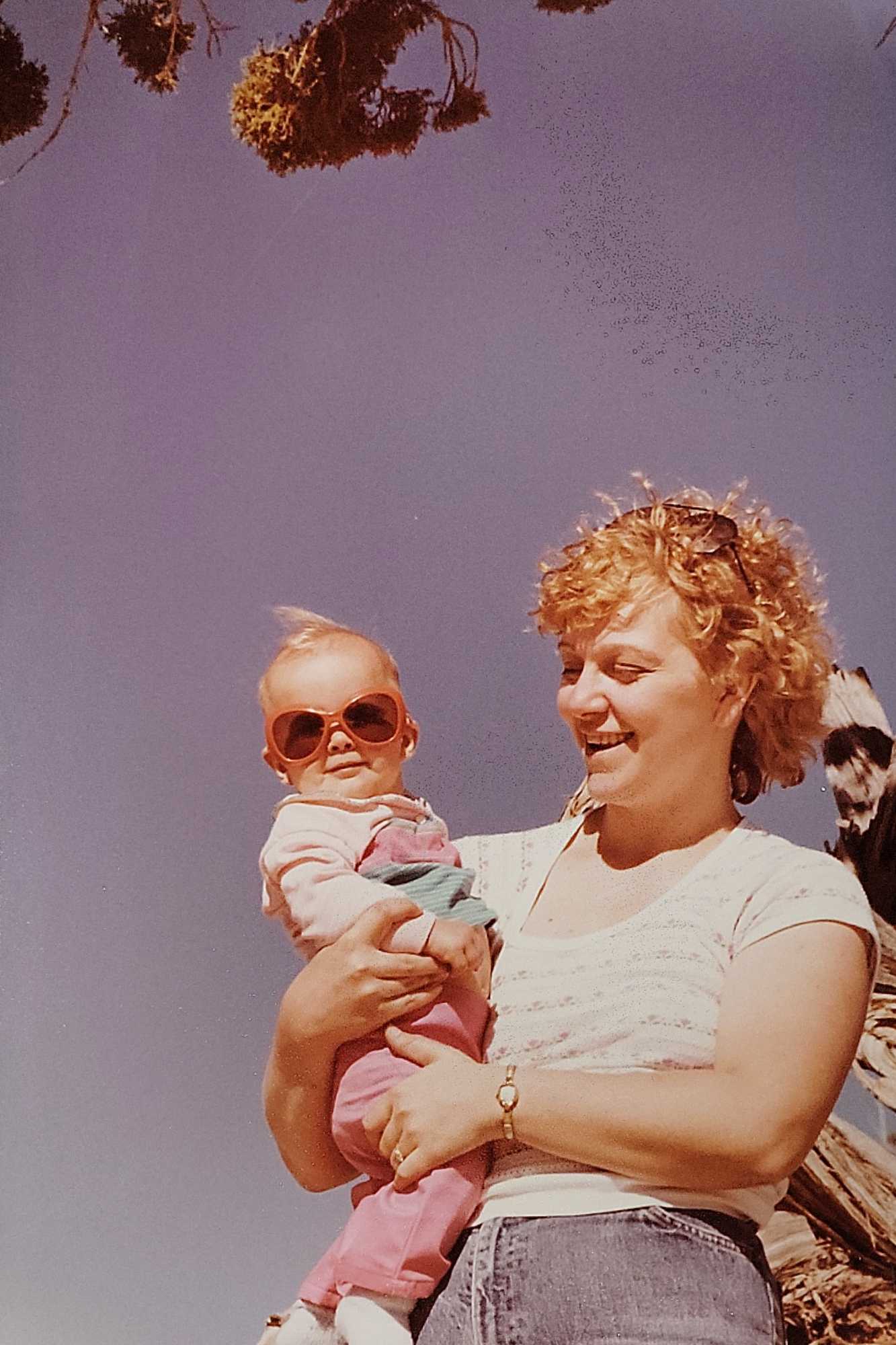

Crocker first met Angela Yeske in a bar called Friday's Child that was on Meadowmere Street near Kraft foods. She was a registered nurse and was out with some of her nurse friends. Crocker was with a few buddies.

“I think I realized fairly soon we matched up well,” she said. “We got along well. It just looked like that was the way things were going to go. It was a feeling.”

They were married a year later in 1977. They have raised three children, now adults.

Does she share his passion for snakes?

“Absolutely not,” she said. “He has only a couple at home now. One or two. He has downsized a lot over the years.”

A menagerie of house guests

Over decades, they have kept assorted other animals at their home, including Sammy, a bobcat.

The bobcat was a female juvenile that, Crocker said, had been “chewed up a bit” by dogs. It had a hip injury. The zoo already had other bobcats on exhibit.

He obtained a permit from the Missouri Department of Conservation to bring the bobcat home.

“She was raised in the house for the first 18 months with two house cats,” Crocker said. “All three cats stayed in an empty bedroom during the day while we were at work.

“Sammy would run through the house, occasionally knocking lamps and other objects to the floor. She loved to jump up and perch on my shoulder. Because of her hip injury, she sometimes jumped a little short of her goal and at such times would sink her claws into my back and climb the rest of the way up.”

Bottle-feeding baby baboons

Sammy grew bigger and Crocker built an enclosure for her in the backyard, where the bobcat lived for 8½ years.

Her presence was no secret in the neighborhood, Crocker said. Each February she would come into heat and her ear-piercing screams could be heard by nearby neighbors.

Sammy was eventually moved to the zoo, where she was exhibited with a few other bobcats. She lived to the age of 18 and is buried in their backyard.

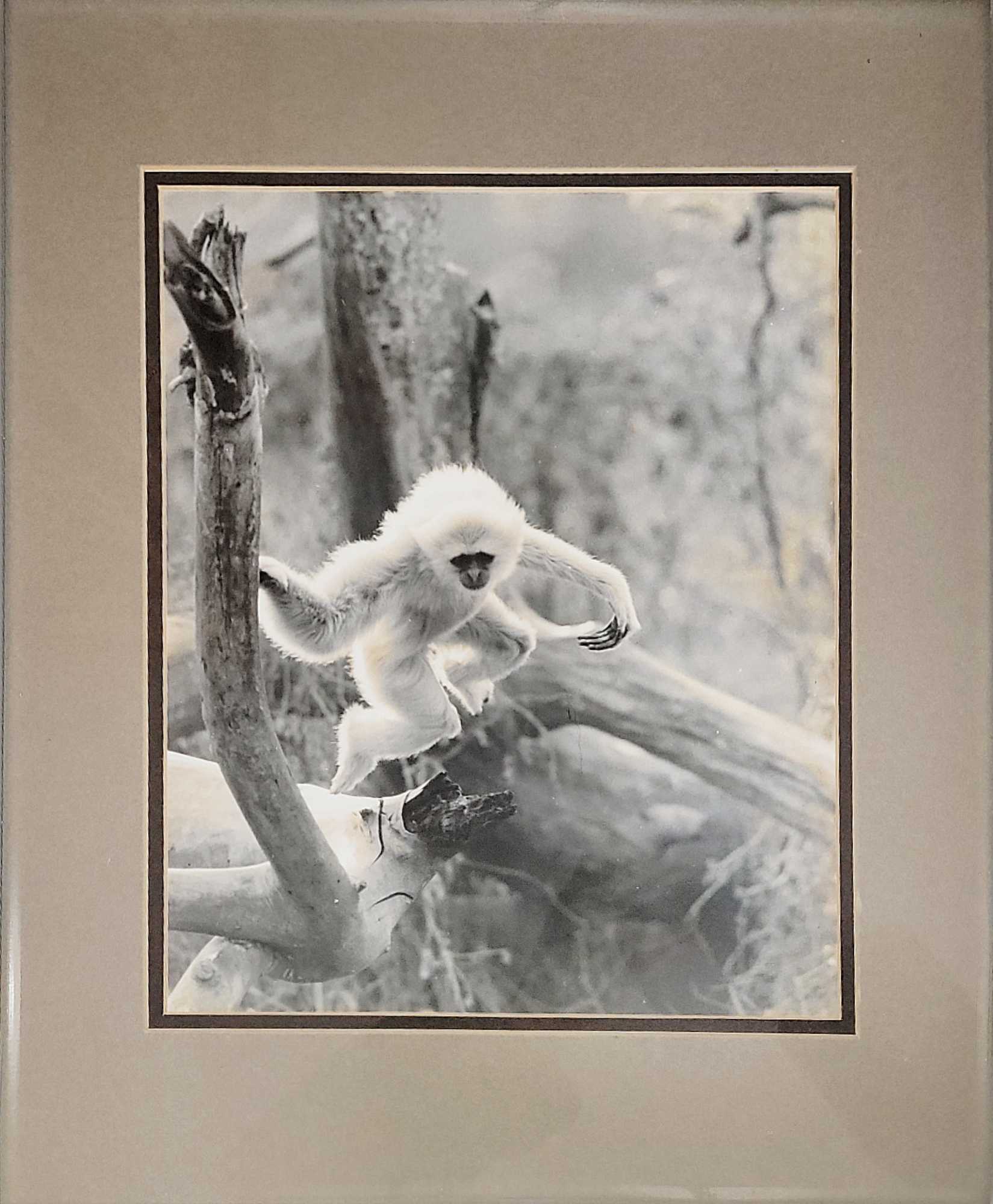

In the early years at the zoo, Crocker said, he also took home baby baboons and baby mountain lions that he and his wife bottle-fed.

“I remember a little monkey that they had to pull from the mother,” Angela Crocker said.

Bubba the tortoise not yet dead

(From “True Tales from Dickerson Park Zoo,” 2021, by Mike Crocker)

In 1990 the big male tortoise Bubba had an abscess on his tail that did not respond well to drug therapy. Our veterinarian decided to surgically remove the mass.

Bubba did not recover from the surgery. The staff detected no respiration, no heartbeat. So, the next day we put the body in the bucket of a backhoe or a skid steer and went to bury it. But before we could put Bubba in the hole it moved and blinked an eye.

It had become so lethargic under the anesthesia that its respiration and heart rate had become undetectable, a common problem with reptiles. Today, we have special equipment to detect those faint pulses and light breathing.

He has a kryptonite; it's wasps

John Smallwood, 74, is another friend Crocker has known since boyhood.

“He was always up for an adventure,” Smallwood said.

“One story that crosses my mind is when we were snake hunting. We were on a hillside. It had lots of rocks, and we were turning them over to find snakes.”

They were in their 20s.

“It was nothing for Mike to grab a snake, even a poisonous snake, or a tarantula.

“He was 50 to 60 yards away from me. I heard him yell and then I saw him running full speed down that hill with a full swarm of wasps right after him.

“It was funny because he is not scared of snakes or spiders, but he was scared of wasps.”

They also would drive to the Branson area to watch collared lizards run.

“They would get up on their hind legs to run and when they did they looked just like little dinosaurs,” Smallwood said.

What you see is what you get

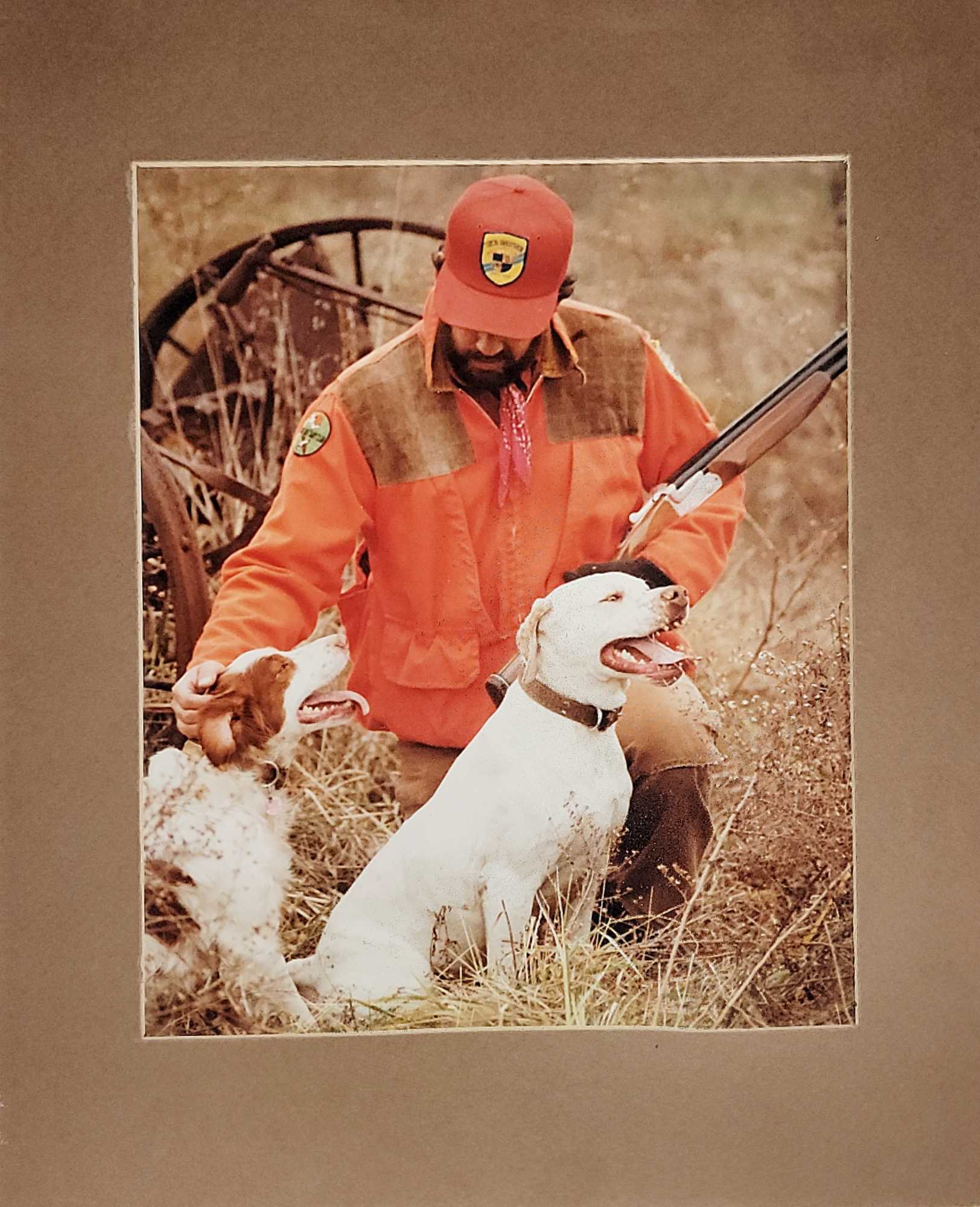

Crocker's greatest joy — not related to snakes — is fly fishing. He is masterful at tying flies, too.

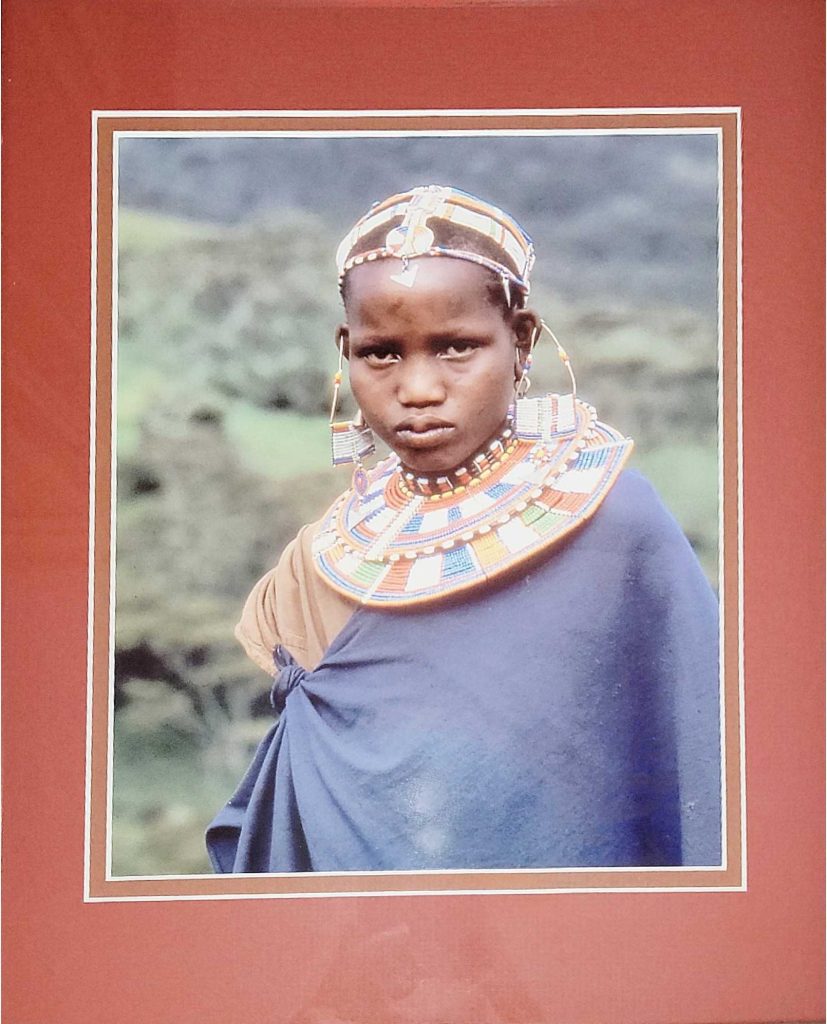

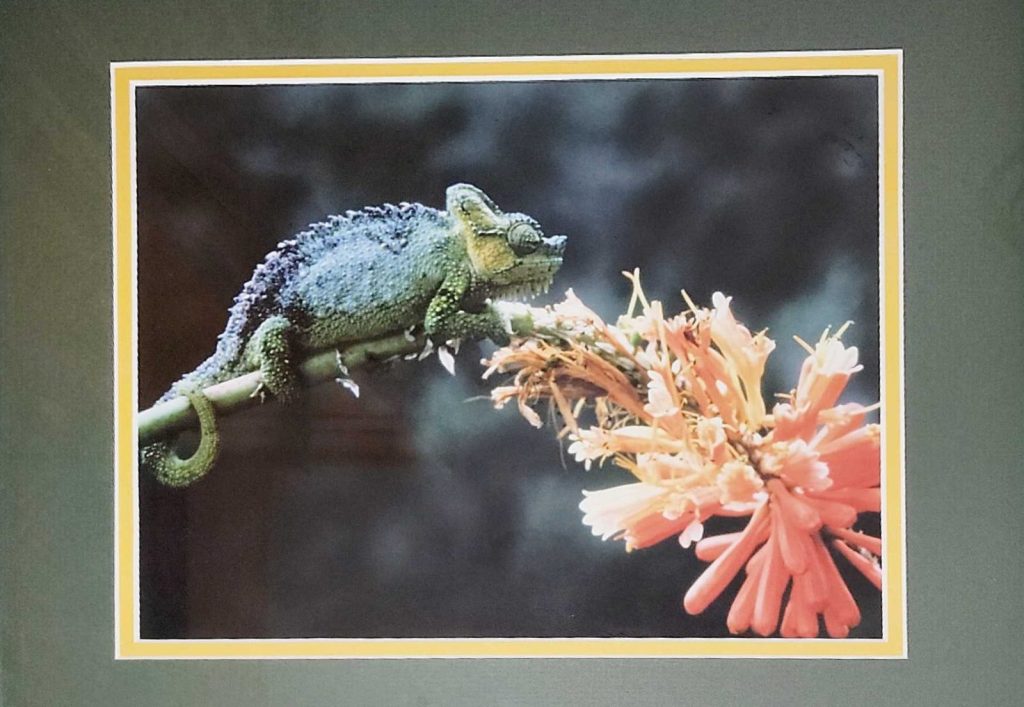

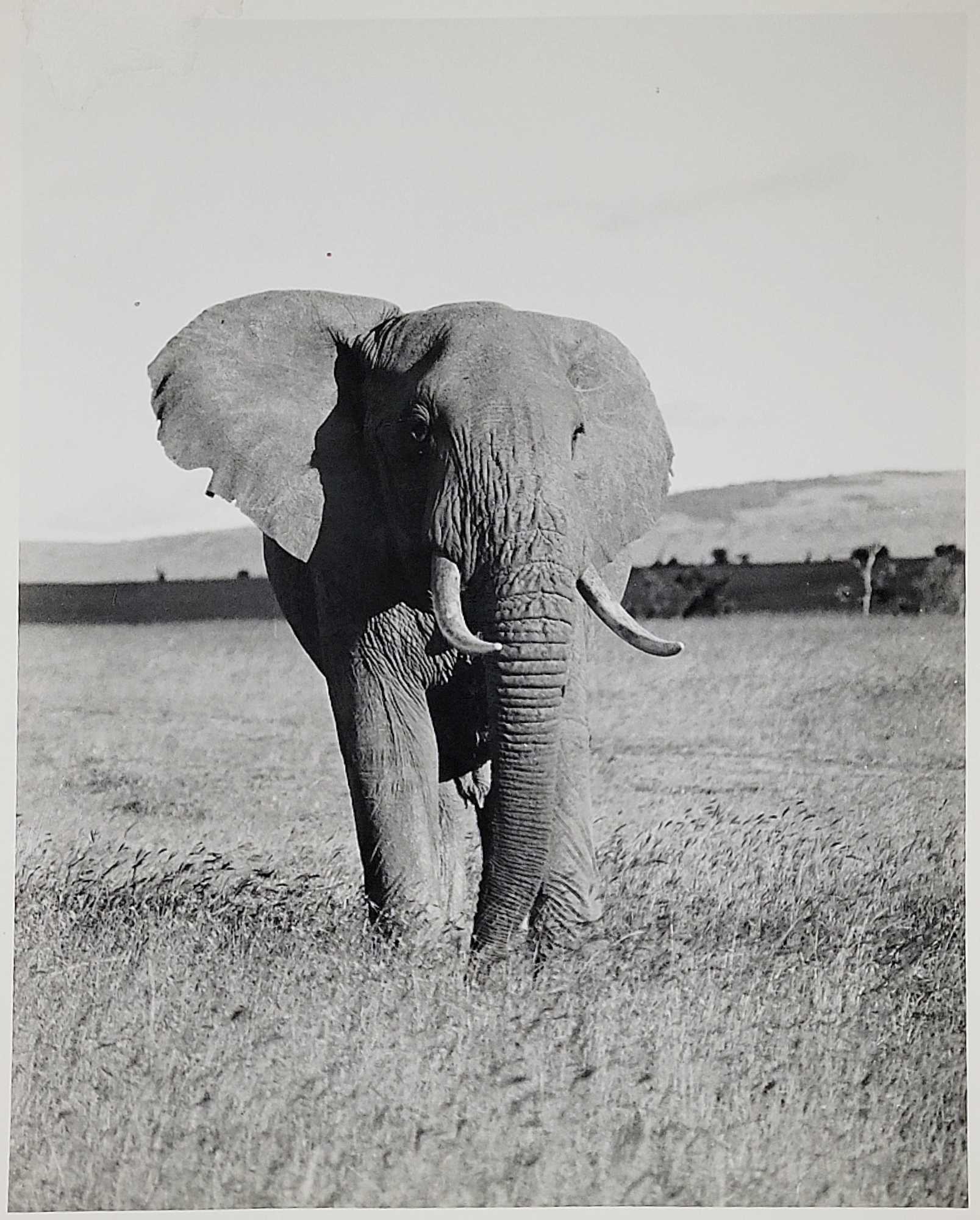

He pursued photography many years, mostly capturing pictures of animals. Some of those photos hang in his zoo office.

“I used to do quite a bit of photography,” he said. “But I got tired of carrying around a 50-pound pack of cameras and lenses. I've either got to be fly fishing or taking pictures — and I find it difficult to do both at the same time.”

Angie, his wife, described him as “quiet, calm, friendly.”

What else?

He likes to do yard work at home. He likes rock music from the 1960s and 1970s.

Does he ever dance?

No.

“He's pretty much what-you-see-is-what-you get.”

Odd glitch in his ability to remember

His wife and friends know him well enough to have noticed an odd glitch in his memory. There have been moments in his life that they consider unforgettable, yet he has no recollection of them. It is not associated with age; he has always been like that.

For example, Crocker has no memory of being fishing with Davis and jumping into a swarm of snakes on Table Rock Lake.

“I'm sure it happened,” he said. “It sounds like me. I just don't remember it.”

His friends tell the story of how they were with him at Dan Bailey's Fly Shop in Livingston, Montana, when Crocker recognized and pointed out Joseph Brooks, a writer and at the time perhaps the nation's most respected fly fisherman. (Brooks was born in 1901 and died in 1972.)

They tell how Crocker went over and chatted with Brooks and then introduced him to his friends from Missouri.

Crocker remembers only this part: He was in the store and saw Brooks there. Nothing else.

“I cannot resurrect the memory. Everybody remembers details from way back — except me,” he said.

Narrow escape from Big Mac, the elephant

(From “True Tales from Dickerson Park Zoo,” 2021, by Mike Crocker)

In 1983, keepers Jeff Glazier, Kenny Qualls, and I were working with the elephants. Onyx was known to the public as Big Mac due to the help of the local McDonald's stores in bringing him to Dickerson Park Zoo.

Onyx had reached sexual maturity and was periodically coming into musth. Similar to rut in male deer, musth causes the testosterone level to elevate and the elephant becomes extremely aggressive.

Onyx lunged at Kenny and hit him in the face, knocking him back ten to 15 feet to the ground. Jeff ran up ahead of me to divert Onyx from Kenny, who was still on the ground. Onyx lunged at Jeff.

One tusk went under each of Jeff's armpits and he lifted Jeff off the ground. With a lightning-fast flip of his head, Onyx threw Jeff backwards several feet. Jeff hit the ground on his feet, running. Onyx whirled and again lunged at Jeff, hitting him a glancing blow.

Jeff's feet continued to churn, running for the yard railing with Onyx right behind him.

You could almost feel the awesome power of the elephant in the air and through the ground. It seemed like the ground thundered from his movements and footsteps. Jeff dived under the railing and out of the yard.

In those days, working with elephants was considered one of the most dangerous of all occupations. I had to pay a premium on my life insurance policy.

His worst day at Dickerson Park Zoo

Crocker's worst day at the zoo involved an elephant. He was at the monthly Springfield-Greene County Parks Board meeting on the morning of Friday, Oct. 11, 2013. (The zoo is under the purview of the parks board, which is under the purview of the city.)

His cell phone suddenly exploded: Elephant keeper John Bradford, a long-time zoo employee, had just been killed by a 41-year-old elephant named Patience.

Bradford, 62, had worked at the zoo for over 30 years.

At that time, elephant keepers at Dickerson Park Zoo — and at most zoos throughout the nation — no longer had direct contact with elephants, as they did with Big Mac back in 1983.

The standard of care of captive elephants at zoos had changed dramatically from decades before when elephant keepers at zoos deployed the methods of elephant keepers at circuses, who often used fear and, at times, brutal physical punishment to try to control elephants.

An elephant can weigh 12,000 pounds and has tusks that can not only toss a man but kill him, as well.

Bradford had leaned his upper body between two thick and tall steel protective columns — spaced about 2 feet apart — in the elephant barn to get Patience to exit the barn, Crocker said. The elephant was in a chute, or passageway, that leads to the yard. It did not want to move.

Bradford used an animal guide to prod Patience through the chute. She suddenly rushed forward with stunning speed and butted his head and upper body; he fell between the protective columns, onto the ground on the elephant's side of the protective poles and she crushed him.

Crocker said emergency responders told him the original blow to the head and upper body is what killed Bradford.

The zoo received media inquiries from around the globe regarding the tragedy, and city staff members were assigned to respond.

Crocker said he heard from many who pleaded that the elephant not be killed. That was never considered, he said. Patience is alive today, one of the zoo's four elephants.

The ostrich that attacked Johnny Cash

(From “True Tales from Dickerson Park Zoo, “2021, by Mike Crocker)

In the late '70s and through most of the '80s, the zoo had a group of ostriches, an adult male and three females. The male was a ruffian. If you get close to a male ostrich, it will flap its wings, open its mouth and might lunge at you. If you went into the yard with him, he was going to come after you.

The zoo bought him from an animal broker who had obtained him from Johnny Cash. It was Cash who named him Waldo.

Waldo had attacked Cash, breaking a couple of his ribs and cutting his stomach so badly he had to be hospitalized.

(Cash mentioned the 1981 encounter in his 1997 book: “Cash: The Autobiography.”

(“All he did was break my two lower ribs and rip my stomach open down to my belt. If the belt hadn’t been good and strong, with a solid belt buckle, he’d have spilled my guts exactly the way he meant to.”)

Dickerson's elephant breeding program

During Crocker's tenure, Dickerson Park Zoo has made national news for its elephant breeding program.

The zoo's first elephant, C.C., born in Thailand, arrived in 1954. She was named after Springfield weatherman C.C. Williford.

The first calf born at the zoo was Kate, in 1991. But that calf, and five of the eight others born at Dickerson Park Zoo, succumbed to elephant endotheliotropic herpes virus, a highly fatal disease that plagues elephant calves worldwide, captive and in the wild.

An elephant can die within 24 hours of a zookeeper spotting symptoms.

In 1997, Dickerson Park was the site of what initially was thought to be a breakthrough in treating elephant herpes virus.

Chandra, a 17-month-old calf, was displaying all the symptoms of the disease. She was lethargic; her tongue had turned from a healthy pink to purple; her major muscles were hemorrhaging.

Zoo staff treated her with experimental doses of famciclovir, an anti-viral medication, and five days later, Chandra was back to normal. This was the first successful treatment. Today, she lives at the Oklahoma City Zoo.

The Association of Zoos and Aquariums in 1997 awarded Dickerson Park's elephant program the Edward H. Bean Award, for “a truly significant captive propagation effort that clearly enhances the conservation of the species.”

In 1999, Dickerson attracted national attention again when Moola became the first Asian elephant to become pregnant through artificial insemination. The calf was named Haji.

Unfortunately, famciclovir did not prove to be a reliable cure. There are multiple strains of the virus. Haji died of herpes virus three years later. Another calf from Moola named Nisha died at age 1 in 2007, also of elephant herpes virus.

At that point, the Dickerson Park Zoo, as well as other zoos, were criticized in some quarters for continuing efforts to breed captive elephants when herpes virus was killing so many calves.

Today, there is no known reliable cure for the disease. Research continues.

More zoos ‘getting out of elephant business'

Dickerson Park Zoo is no longer an elephant breeding facility, Crocker said. In fact, elephants are becoming increasingly difficult for zoos to obtain.

“More and more zoos are getting out of the elephant business,” he said. “I suspect that eventually, we will, too.”

First, he said, fewer elephants are available in the wild. Second, the trend in zoos is to establish herds, which is a more natural environment for elephants, and to provide these herds more space.

Larger zoos now often pool resources to spend millions for elephants, he said. Smaller zoos cannot compete at those prices.

When there are successful births in captivity, he said, the big zoos are not apt to part with the young elephants.

No two days at a zoo ever the same

Working at a zoo, Crocker said, means no two days are the same.

“The zoo is a living, breathing entity,” he said.

“There are animal births and deaths, new animal arrivals, animal injuries, animal escapes, animal incidents outside the zoo to help with, animal rescues, animal attacks, human medical emergencies.”

And no two animals, even of the same species, are the same, he said.

“Animals, like people, are individuals. There may be characteristics in species in general, but they each have individual personalities.”

His career at the zoo has been filled with surprises.

“You can never really predict things,” he said. “You build an exhibit based on experience. But something happens that you never imagined an animal could do.”

You had to see it to believe it

For example, he recalled the stunning sight of an 18-inch-tall muntjac, a small deer from Asia, bounding effortlessly over an 8-foot enclosure fence.

“We had a ring-tailed lemur on the island at the zoo. It got off the island by leaping from a branch on a high tree on the island to a branch on the far shore of the lake. We cannot prove that that is what happened, but that is where we found it.

“We had a giraffe on birth control. It got pregnant and had a calf. We did not want to breed it. Something went wrong with the birth control. We were all shocked.”

Python attacks him, don't wake up the wife

(From “True Tales from Dickerson Park Zoo,” 2021, by Mike Crocker)

The Burmese python was 9 or 10 feet long. I was carrying it back to its cage when it struck. Its teeth got caught in the fabric of my blue jeans and I reached down with my right hand and grabbed it behind the head before it could turn loose and strike again. But the snake instantly coiled around my hand and leg, pinning my right arm to my right leg.

I tried to get it off with my left hand, but it was too strong for me with only one arm. I continued to struggle for a few minutes, to no avail. My wife was home asleep, unaware of what was going on. I decided it was best not to wake her. She had seen me get bitten by big snakes a few times and bleed quite a bit. She did not like big snakes for that reason.

I hobbled into the house and with my free hand punched the buttons on the wall phone to call my friend, Laverne Copeland, who lived a few blocks up the street. He had been my mentor in the world of reptiles and was the zoo's reptile keeper at the time.

By the time he got there — probably no more than 8 to 10 minutes had passed since the snake first grabbed me — my hand had turned blue and my arm and hand were limp, hanging at my side, a result of the blood circulation being cut off by the powerful constriction.

I don't recall when, or if, I ever told my wife about the incident.

Right guy to be in charge in an emergency

Paul Price, 68, worked at Dickerson Park Zoo 1974 to 1987. He later became director of Riverside Discovery Center, formerly called the Riverside Park and Zoo, in Scottsbluff, Nebraska.

Price is retired these days and lives in Fair Grove. He most recently saw Crocker when Crocker visited Price's 30 acres in the summer to witness in nature the “communal breeding of broad-headed skinks,” Price said.

Crocker was the right man for the top job at Dickerson Park Zoo, Price said.

“Mike is very calm and stabilizing,” he said. “He is caring. He is kind. He does a lot of stuff for the community that nobody knows about. He's probably donated a hundred gallons of blood, and he volunteers to teach first aid and CPR for the Red Cross.”

Crocker paid his dues by working many jobs at the zoo, Price said.

“At a small zoo you have to do just about everything,” Price said. “And Mike has. Mike had that experience handling snakes and reptiles. But later you have to be the finance man. The marketing man. At a small zoo you can learn more than in a big zoo.”

A lot can go wrong at a zoo, Price said, and you don't want someone in charge prone to panic.

“Mike is real good at handling situations that are emergency situations — everything from snake bites to tiger escapes.”

The day a tiger got loose on a busy day

“One time there was a tiger escape with Mike in charge over the weekend. He was in charge on Saturdays and I was in charge on Sundays,” Price said.

“He had a tiger get out when there were like 3,500 people in the zoo,” he continued. “He had the proper training. And he has a really calm demeanor. They had that thing back in 25 minutes, and it never made it in the papers.

“That's what every zoo director wants — stay out of the news.”

Crocker confirmed the account, which he mentioned in his book. It happened in 1983, and the tiger was a female named Horsefly, which was shot with a tranquilizer dart. In the book, the escape happened on a Sunday, not a Saturday.

“We had a lot of people at the zoo,” Crocker recalled in an interview. “I don't remember a number. We went into lockdown and got all the people into buildings. It went well. Nobody got hurt. And the tiger didn't get hurt.”