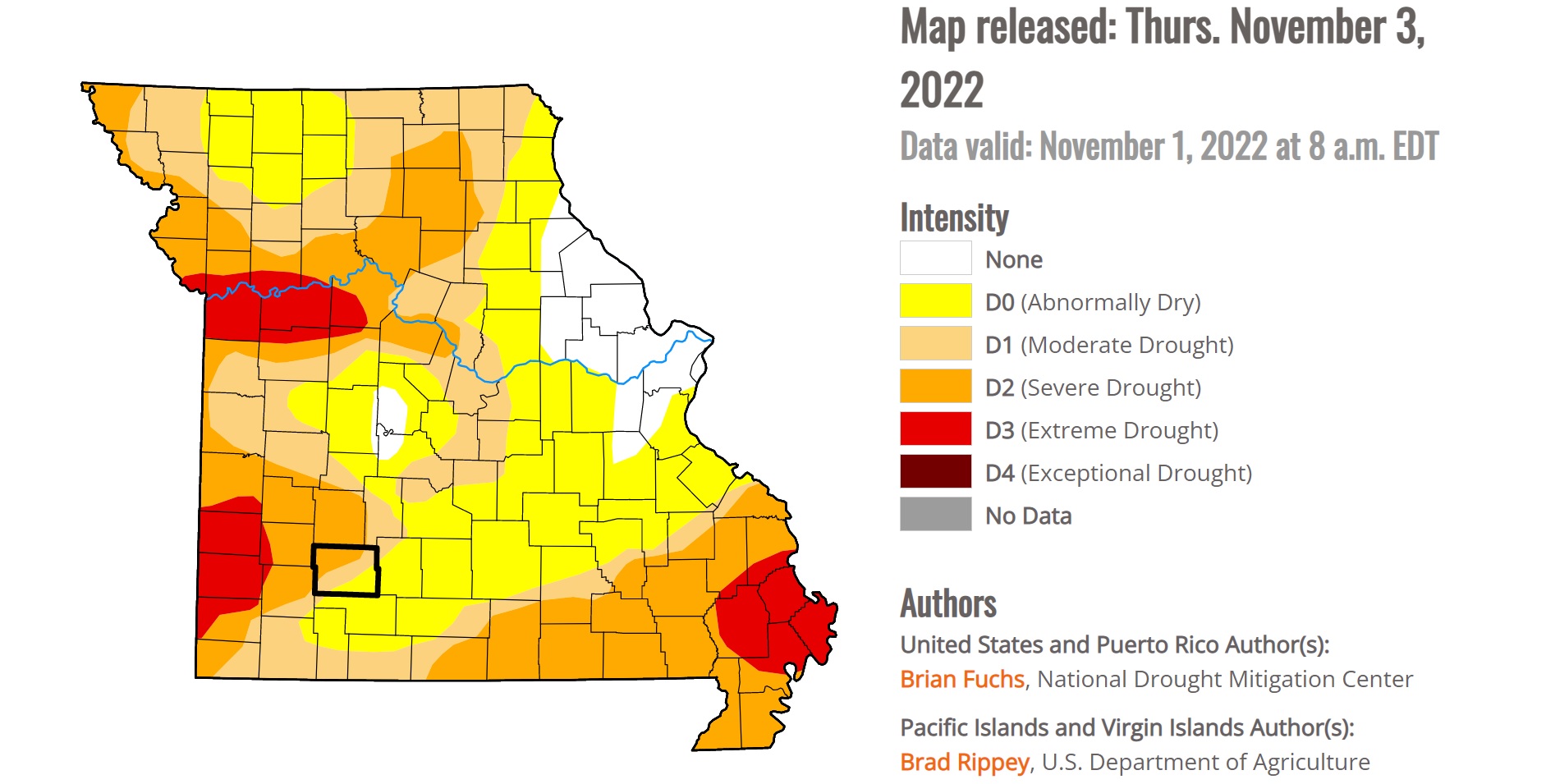

Southwest Missouri’s economy would take heavy hits during a long, severe drought. Some of the state’s top environmental engineers believe Southwest Missouri also has a good degree of drought resilience built up.

The top minds in water and public utilities discussed drought and water resources as the Southwest Missouri Joint Municipal Water Utility Commission, commonly SWMO Water Commission, put on the 14th iteration of its Southwest Missouri Water Conference in early November at the Darr Agricultural Center in Springfield.

To boost the Springfield metro area's resistance to drought, the SWMO Water Commission wants to buy assured access to surface water from Stockton Lake. The conference included a keynote presentation on drought on the Colorado River basin in the western United States — drought that serves as a large-scale example of what could happen in Southwest Missouri.

SWMO Water Commission Director Roddy Rogers said there is no future if there is no water, and he encouraged conference attendees to take that message of making water a top priority back to their city governments.

“There’s always more priorities than there is money,” Rogers said. “As a water person, I’m biased. I think it needs to be on that list, it needs to be near the top.”

Elizabeth Kerby, an engineer with the Missouri Department of Natural Resources Water Resources Center, gave a briefing on a pending update to the 20-year Missouri Water Plan set to drop later this month.

Kerby explained the assessment measures the likelihood of drought, susceptibility to drought, impact in economic value and resilience, or how quickly a region can respond and recover from severe drought.

According to the assessment, based on scale of 1-9, the potential impact of severe drought on Southwest Missouri rates a 9. While the reasons are many, the two largest reasons are the prevalence of agriculture in the southwest region’s economy, and the importance of water to the recreation and tourism industries.

“Missouri is a large producer of crops and livestock, as they provide a lot of economic value to our state,” Kerby said. “Drought can cause catastrophic damage to land, and between the years 1980 and 2021, an estimated $252 billion in value has been destroyed from drought in the U.S. It’s essential for Missouri to be prepared in case drought approaches quickly.”

To assess the potential economic impact of a drought, the Department of Natural Resources estimates the impact a lack of water would have on crops, livestock, municipal water supply, recreation and thermal power generation.

“These sectors all hold equal value in our analysis,” Kerby said.

The assessors gave Southwest Missouri a 5 rating in drought susceptibility, a 4 rating in drought resilience, and an overall drought vulnerability rating of 5 on the 1-9 scale.

“I was glad to hear that we are seen as maybe one of the more resilient (regions),” Rogers said.

‘No water, no future’

Planning ahead can help reduce the impact of drought once it begins.

“It’s going to cost a lot to do it, but it’s going to cost a lot more not to do it,” Rogers said.

According to the Congressional Research Service paper “Drought in the United States,” the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) estimates the United States spent more than $285.5 billion responding to droughts from 1980 to 2022, a 42-year span that included 29 individual billion-dollar drought events.

Stockton Lake is a supplemental source of water for Springfield, but the SWMO Water Commission sees it as a potential source of water for Springfield and several surrounding cities, including Nixa, Mt. Vernon and Monett. The Stockton pipeline was built in 1996, and while it was somewhat controversial, Rogers said it was also a good example of forward-thinking when it comes to water sourcing.

“Springfield did this 30 years ago,” Rogers said. “When we went through those very short-lived droughts[...] in the mid-'90s, ‘06-’07, 2012, we wouldn’t have made it without the allocation we had. And I hope that 30 years from now, people are sitting here saying that we all did the right thing, too.”

The Stockton Pipeline is 30.1 miles long and 36 inches in diameter. It takes water from Stockton Lake to Fellows Lake, and that water is then pumped to the Blackman Treatment Plant in east Springfield. Fellows Lake is Springfield’s primary source for drinking water, according to a source water protection plan filed with the Watershed Committee of the Ozarks. The pipeline can currently deliver 20 million gallons per day to Fellows Lake, McDaniel Lake and a pump station at Fellows Lake.

In 2013, Springfield elevated its drawing capacity from Stockton Lake from 15 million gallons per day to 20 million gallons per day after a severe drought in 2012. A proposal for a third allocation is under review by the Army Corps of Engineers, as part of Springfield’s membership in the Tri-State Water Coalition. Springfield also gets some of its drinking water from groundwater, with wells at Fulbright and at a well off of South Kansas Avenue.

Water for Springfield, surrounding towns

Water can be moved and water can be stored, but water can’t be created. That’s why the SWMO Water Commission wants to strike a deal with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to buy a stake in the waters of Stockton Lake.

“If there is a bowl, and we’ve got our slice, our storage in that lake,” Rogers said. “There is a certain amount of water in that storage, and we can use it. It’s reserved for that purpose, just for us, and we will pay for that.”

A purchase agreement has been under negotiation for years. The Stockton pipeline and Fellows Lake would be a key spoke and hub in a network that could pipe surface water as far away as Joplin. The Corps of Engineers has been performing a reallocation study on Stockton Lake, and according to a 2018 piece in the Joplin Globe, results have been delayed multiple times. Rogers hopes the SWMO coalition has an answer from the Corps of Engineers within the next year.

“It’s not a five-year or a ten-year project, it’s a decades-long effort and it’s a very long process with a lot of things involved, and we’ve got to be ahead of it,” Rogers said.

The people involved with the project and the negotiations change over time as people change jobs and join and leave the organizations involved. It’s hard to have a continuity of work on the project, Rogers said.

“I would hope that all of our communities, Springfield, the smaller ones, Joplin, the western communities, would all put water on their list of priorities, even towards the top, and be prepared to be part of this effort,” Rogers said. “You’ve got to do things that you might not get to see the benefits of, but it’s going to benefit those who come after us.”

Water consumers and their role in conservation

Communities that would buy surface water from Stockton Lake would end up passing on some of the costs for piping the water through consumer rates.

“It involves cost, so you’ve got to get people now to pay for something that they may not benefit from, but their kids, their grandkids will,” Rogers said. “Yes, that is a challenge, because ultimately it becomes a rate issue and the rates have to cover that for these different utilities, different entities, and people are going to want to know, ‘What do I get out of it?’ Well, we get a solid future. Those who came before us did it for us, it’s time to pass it on.”

Rogers said it’s important to encourage people to be conservation-minded about their water, even simple steps like turning off the faucet while they brush their teeth.

“We’ve got to encourage that wise development and taking care of our resources, but I also think we need to take the opportunity to move water to where it’s needed, to where the people are,” Rogers said. “We have to be resilient in establishing resilience, and the key there is moving water to where it’s needed.”

He also encourages larger actions, like using less water for lawn irrigation, and to consider a community’s water supply and sources before relocating into that community.

“We put more water on our lawns in a day than a lot of Third World families use in 60 days just to survive,” Rogers said.

Stockton Lake is presently at about 70 percent of its water storage capacity. A water watch would be triggered if the storage level drops below about 60 percent of capacity.

‘Water is king’ in the Colorado River basin

Alex Pivarnik served as one of the key speakers at the water conference. He is a Colorado River hydrologist with the U.S. Bureau of Land Reclamation. The Colorado River supplies water for the nation’s largest wholesaler of water and second-largest hydroelectric power producer. It is the “hardest working waterway” in the nation, because it serves 17 different states plus farming operations in Mexico.

“We essentially control the water supply on behalf of the lower basin states to meet our requirement to Mexico,” Pivarnik said. “We develop annual operations plans for the reservoirs and dams on the river.”

Lake Mead and Lake Powell are primarily storage lakes.

“The power generated is the byproduct of the water that’s needed for supply,” Pivarnik said. “Water is king.”

Looking at long-range forecasts, Pivarnik said there is about a 30 percent chance the water level at Lake Powell’s Glen Canyon Dam could drop below the power pool level in 2024. The U.S. Bureau of Lake Reclamation, which controls the dam, could look at retrofitting the dam to allow for water passage and power generation at lower levels, even levels considered to be “dead pool” at present. Dead pool occurs when the water level upstream from a dam is so low that it is not possible for the operator to allow any water to pass through the dam.

Drought in the West started in 2000. The storage levels in Lake Mead and Lake Powell dropped from 100 percent to 30 percent of capacity.

In 2007, the U.S. Bureau of Land Reclamation rolled out the Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead in response to the worst drought on record since the federal government started keeping records on the Colorado River. The plan did away with a “use it or lose it” style of water allocation, where entities would pump water from Lake Mead every year and store it somewhere off stream.

“This allowed people, specific entities, to use Lake Mead as a bank, so what they’ll do is they’ll leave that water in Mead with the ability to draw on it at later times, instead of culling it and pumping it into the ground somewhere,” Pivarnik said.

A similar concept of incentives for conservation could play out in Southwest Missouri, with the idea that cities and water districts could be paid up to $2,500 not to use water.

Mandatory water use reductions for seven states came with the guidelines. As a result of the plan and the use reductions, Lake Mead gained about 2.85 million acre feet of water. Still, the drought conditions are persistent and easy to spot. Pivarnik showed the water conference attendees a photo of the “bathtub ring” on Lake Mead. The ring is the high water mark on the rock walls on either side of the lake near Hoover Dam. The top of the ring is about 160 feet above the water level.