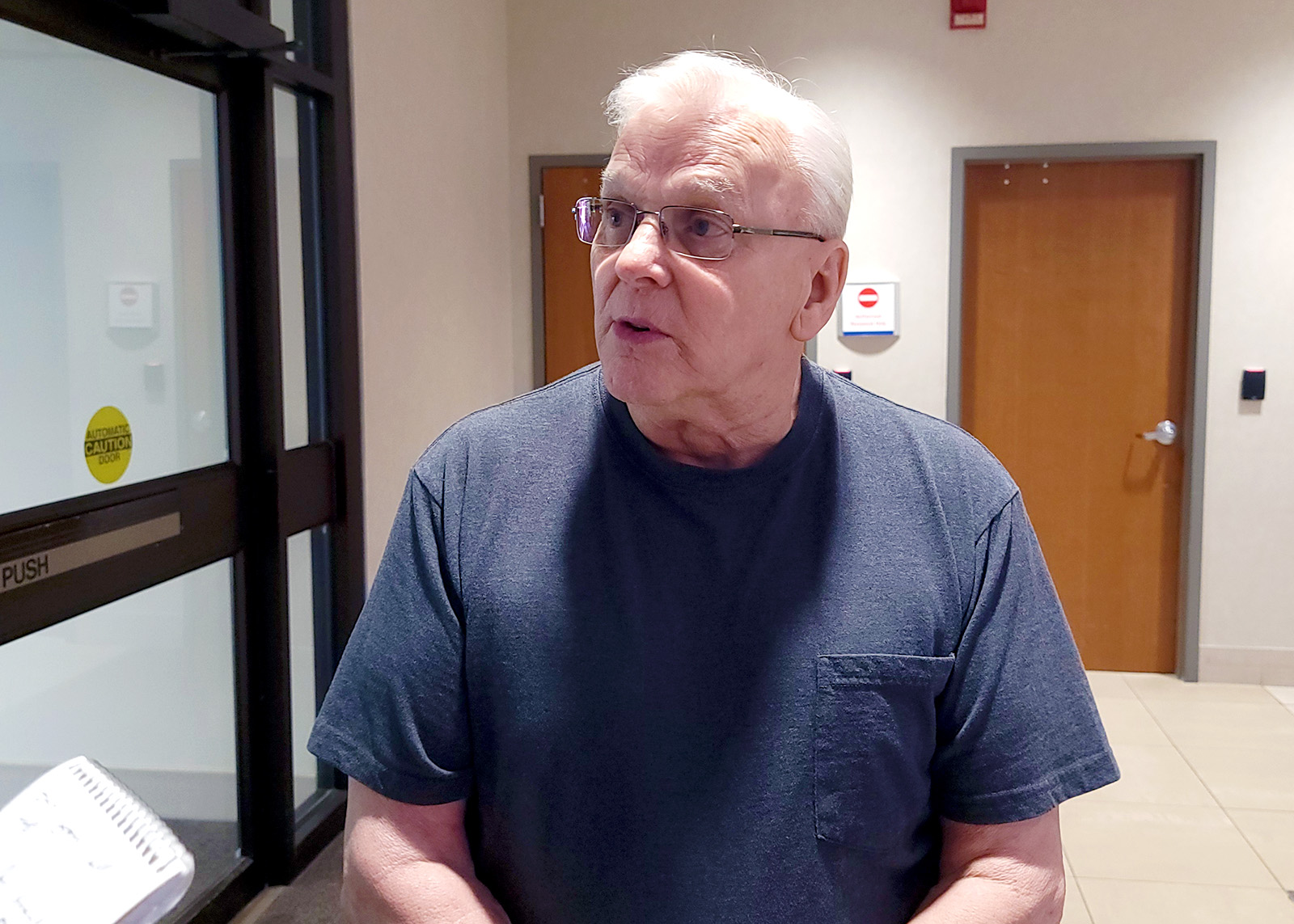

Lloyd Sanders learned two months ago that he had prostate cancer. As difficult as that news was to process, Sanders said it was made more challenging when he learned during a follow-up visit with his urologist that he was not a candidate for surgical removal of the prostate.

“My eyes glazed over and I had to avert my head because I was starting to cry,” Sanders, 70, said.

“And he didn't feel that I was a suitable candidate for chemotherapy, but he was referring me to radiology. I was skeptical about it for the simple fact that general radiology treatment is just a treatment, you know? And it is a treatment that affects multiple organs in the body. The prostate is about the diameter of walnut, but the radiation is affecting my bladder, my rectum, my urethra.”

But Sanders learned he was a candidate for a form of precision radiation treatment delivered through a robotic device now housed at Mercy’s C.H. “Chub” O’Reilly Cancer Center, the CyberKnife S7 system.

Accuray, the company that makes the CyberKnife device, touts its precision in delivering stereotactic radiotherapy with sub-millimeter accuracy. Mercy Springfield recently purchased the latest model, and in mid-April began offering the treatment to patients with tumors that cannot be surgically removed.

On May 10, Sanders was on hand as dozens of Mercy staffers gathered to offer a blessing for the latest cancer fighting tool available in Springfield. As radiation oncologist Kimberly Creach read from Psalm 8 and Mercy chaplain Merrill Williams said the CyberKnife was the latest example of God and people working together to accomplish God’s purpose.

Sanders, who will begin receiving treatment later this month, exclaimed, “Hallelujah,” in response.

Shorter treatment time will save Lebanon patient several trips to Springfield

Prior to opting for care from the CyberKnife and the team of radiation oncologists that operates the new system, Sanders read a number of clinical studies and crunched some numbers of his own. Had he opted for traditional radiation treatment, Sanders, who lives in Lebanon with his wife, would have had to travel to Springfield for about three dozen appointments over several months. The CyberKnife treatment is typically conducted over five sessions in a week or two weeks' time. That equated to about 3,000-4,000 miles of road less traveled for what Mercy doctors told Sanders should offer similar treatment results.

“This is a very effective treatment with equivalent outcomes, in most (cases), but much quicker and most importantly, painless,” said Nathan Tonlaar, radiation oncologist at Mercy. “Because the CyberKnife is a virtual knife, not a real knife.”

On Wednesday afternoon, Tonlaar was all smiles as he showed off the S7. “It’s a beauty,” he told fellow Mercy staffers as they watched the device take aim during a demonstration on a skull that contained, as far as the CyberKnife’s programming was concerned, a brain lesion.

Sanders studied the massive machine as it trained its beam on the skull and rotated and revolved around the target. A few minutes earlier, Sanders explained why he was willing to share his medical story with a reporter.

“I've got a friend that had had surgery done and had his prostate removed,” Sanders said. “And it really breaks my heart. Because the man is now having urinary problems, bowel problems, wearing adult diapers. And my heart aches for him for the fact that I've been offered this opportunity and he's having to deal with a lifetime of problems.”

For one patient, treatment has been ‘piece of cake' so far

“As some of you know, we've been using this technology for about 17 years here at Mercy, and this is the latest and greatest in that line of technology,” Tonlaar said. “And we are very grateful that we've been blessed with this machine.”

After training sessions held at other hospitals and practice runs with physicists and Accuray vendors on site in Springfield, the first Mercy Springfield patient received treatment with the CyberKnife in April, Tonlaar said.

Jim Ayres received his second treatment with the CyberKnife May 10. During a checkup several months ago, Ayres said spots were discovered on his lungs, and his doctor suggested radiation treatment to keep them under control. The morning after his first treatment, Ayres, 82, said he mowed the lawn. After his second, he was walking around the Chub O’Reilly Cancer Center without any pain.

Ayres described the CyberKnife treatments he’s received so far as a “piece of cake” compared to an operation he underwent almost a decade ago.

Ayres in 2015 found out he had prostate cancer. In response, he had his prostate removed and underwent 38 radiation treatments. The surgery was performed by a robot, involved six small incisions and left him looking “like somebody took a baseball bat to me,” he said. Even the post-operation ride home from the hospital was painful, he said, but Ayres made it through. His experience with the CyberKnife, he said, has been a painless one.

Speed and accuracy matter

Tonlaar said the new device offers three advantages. It’s a quick treatment, conducted over five days compared to multiple weeks for patients receiving care for tumors in their prostate, pancreas, lungs, spine and brain, among other areas. It’s also an accurate treatment that uses artificial intelligence to aim at a pre-placed tracker marking the location of the tumor, Tonlaar said.

“Because you can better spare normal tissue, the CyberKnife allows you to deliver something called an ablative dose, a much higher dose of radiation compared to traditional treatment,” Tonlaar said.

Sanders, a Vietnam War veteran whose treatment is being covered through the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, likened traditional radiation to a shotgun blast.

“You may get a couple of pellets inside the target, but the rest of it goes on the outside,” he said.

The CyberKnife, as Sanders described it, offered the precision of something more like a .22-caliber rifle. At the outset of his treatment, Sanders said, Mercy staff will place “markers” inside his prostate.

“And this CyberKnife system targets those markers,” he said. “The prostate rolls and moves, even during breathing. And that CyberKnife system targets that prostate and every shot is spot on. Spot on.”

Body movement has long been an enemy of precise radiation treatment. Neelu Soni, chief medical physicist at Mercy Hospital Springfield, said when patients are receiving CyberKnife treatment, they are placed in a form-fitted mold that looks a lot like a memory foam mattress and helps to maintain a patient’s position throughout treatment sessions. The latest CyberKnife, Soni said, is designed to better track the tumor’s every movement, no matter how small.

“When you have a really tiny target, every millimeter counts,” she said. “So this machine gives us confidence of 0.2 millimeters.”

For Sanders, the demonstration and the blessing gave him immeasurable confidence. Asked what he plans to do once his treatment concludes, he answered with one word:

“Living.”