IN-DEPTH |

The number of people experiencing homelessness in Springfield is a topic often discussed at city council retreats, funding meetings, and among service providers and nonprofit leaders.

Sometimes, it’s hotly debated on social media.

Some organizations that serve the unsheltered population use very different data when they talk about the number of people who are unstably housed.

Why care?

Community awareness about the growing unsheltered population in and around Springfield is important, as it helps guide funding and resources from the government, service providers and nonprofits.

Having vastly different numbers floating around about the actual number of unsheltered people can be confusing to the public.

The Connecting Grounds, a church that serves the homeless community in Springfield, estimates there are nearly 2,500 people who meet the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's (HUD) definition of homelessness in and around Springfield.

Other organizations, like staff with the Gathering Tree and Eden Village (tiny home communities for homeless people), say it’s probably more like 550 or so people living in camps, vehicles or on the streets of Springfield.

Last year’s point-in-time count found about 450 homeless individuals in Springfield.

What is the point-in-time count? (Click to expand)

The point-in-time count is a count of sheltered and unsheltered people experiencing homelessness that HUD requires each Continuum of Care nationwide to conduct in the last 10 days of January each year. A Continuum of Care is a local planning body that coordinates housing and services funding for homeless families and individuals. Here, the CoC is called the Ozarks Alliance to End Homelessness, and it is made up of representatives from organizations such as Catholic Charities and Community Partnership of the Ozarks.

The Department of Elementary and Secondary Education “count” of Springfield Public School students who are eligible for homeless services — known as McKinney-Vento eligible — jumped from 1,134 in the 2017-2018 school year to 1,283 this current school year.

A recent social media post brought to light the issue of how and why different groups count and define homelessness in different ways.

Community Partnership of the Ozarks recently shared on Facebook that there are about 78 chronically homeless households in this community. An asterisk denoted that the number was referencing those households who are active on the prioritization list for supportive housing services.

Some people took issue with this post, arguing that more context should have been given about what defines a “chronically homeless household” and what the “active prioritization list” actually means.

After all, one could stop by the daytime drop-in center for unsheltered people in downtown Springfield on any given day and count more than 78 people.

“This info seems misleading,” one person commented on CPO’s post. “This representation drastically downplays the current needs in our community.”

Connecting Grounds Pastor Christie Love also took to social media to express her frustration with the post, writing:

“There is a large gap between this number and the reality on the streets of Springfield,” Love wrote in part. “We MUST stop minimizing the need in our city.”

So what gives? Why are the numbers so varied from group to group? Is it even possible to know how many there are given the mobility of the population and that many are living in cars, abandoned buildings and encampments — and that some may not wish to be found and counted in the first place?

CPO relies on its prioritization list. What does that mean?

The Daily Citizen reached out to CPO’s homeless services leadership team, Michelle Garand and Adam Bodendieck, to ask about the social media post.

Bodendieck is the director of Homeless Services, Affordable Housing and Homeless Prevention. Garand is the vice president of Affordable Housing and Homeless Prevention.

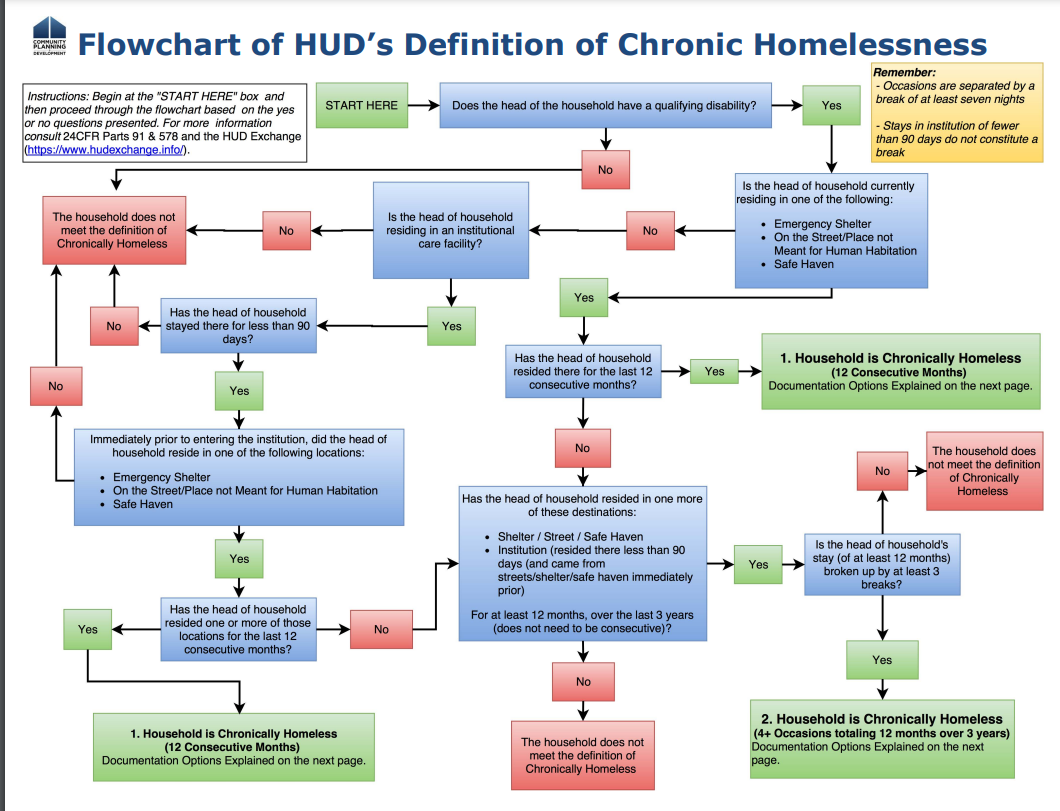

“We didn’t necessarily clarify the full definition of chronically homeless, which we should have,” Bodendieck said. “This is the HUD definition of chronically homeless: you have a disability and you have experienced homelessness for a period of 12 consecutive months or for 12 months over at least four episodes broken up by seven nights over the past three years. So it’s a very specific definition.”

And those 78 households are ones that are checking in with the staff at One Door to update their information every 90 days, which keeps them active on the prioritization list. There are no doubt many unsheltered individuals who do not check in with One Door every 90 days.

(One Door is a CPO program housed at the O’Reilly Center for Hope. One Door is this community’s “point of entry” to homeless services.)

Bodendieck went on to explain that the number of chronically homeless people typically makes up 17 to 20 percent of the total homeless population in our community, which is a little higher than the national average of about 10 percent.

There were 846 people on the prioritization list as of Nov. 10, Bodendieck said. Of those, 78 households meet HUD’s definition of chronically homeless and are prioritized for programs and services.

The social media post that caused a bit of a stir was part of CPO’s month-long campaign for National Homelessness Awareness Month. Each week in November, CPO is sharing posts with information about a specific homeless population. The following week, CPO shared a post about veteran homelessness.

The many nuances of HUD’s definition of homelessness

Bodendieck and Garand invited the Daily Citizen to come to their offices at the O’Reilly Center for Hope to learn more about how they count unsheltered individuals, the definitions they must use, and why their organization’s numbers are so different from other counts.

HUD uses four categories to define homelessness, Bodendieck said. But it’s Category 1 and Category 4 who qualify and are prioritized for HUD-funded housing support programs. These are the individuals and households who go on the prioritization list.

- Category 1 are people who are experiencing literal homelessness, Bodendieck explained. They are either unsheltered, in an emergency shelter or in a place not meant for habitation (a tent, vehicle or abandoned house, for example).

- Category 4 are those who are fleeing or attempting to flee domestic violence.

People who meet either of these definitions qualify for rapid re-housing or permanent supportive housing programs. However, there are not enough rapid re-housing and permanent supportive housing beds available for everyone who needs them. And that’s why there is a prioritization list to get into a rapid re-housing or permanent supportive housing program.

People are prioritized with those who are at most risk at the top of the list. For those eligible for housing program assistance, local prioritization factors include vulnerability and length of time experiencing homelessness.

The other two categories used by HUD are:

- Category 2 are people who are at imminent risk of homelessness.

- Category 3 are those who are “homeless under other federal statutes.”

If a person does not meet HUD’s Category 1 or Category 4 definitions of homeless but they are in need of housing support — such as those in Category 2 and 3 — CPO has other prevention and shelter diversion programs that might be of assistance.

What does ‘chronically homeless' mean?

HUD defines “chronically homeless” in very specific terms. Take a look at HUD’s flowchart designed to help people figure out if they meet the criteria:

“If it’s only been three episodes (of homelessness over the past three years), well, then you don’t meet the definition of chronic,” Bodendieck said. “You’ve got to figure out to the best of your ability and make the best use of what you do have available and make sure when it comes to rapid re-housing or permanent supportive housing, that you are matching the interventions up to those who desperately need that.”

So that “78 chronically homeless households” that are “active on the prioritization list” mentioned on social media is a fairly small and specific portion of this community’s unsheltered population.

Garand and Bodendieck agreed: context and definitions matter when it comes to sharing data with the public. But it also matters because they are beholden to HUD and all the requirements that come with that.

“I like being confident in the methodology,” Bodendieck said. “These numbers are not definitive or anything, but I can at least tell you where they came from and why and what they entail and what they encompass and what they mean. I think that provides good dialogue around the issues.”

CPO uses HUD’s strict definitions

It’s important to note that since 1996, Community Partnership of the Ozarks has contracted with the city of Springfield to fulfill local HUD mandates and facilitates the Ozarks Alliance to End Homelessness (this community’s HUD-designated regional planning body for coordinating homeless services and funding).

CPO must follow HUD requirements and definitions when collecting data related to homelessness.

Groups like The Connecting Grounds can use very practical and common-sense measures to count the number of people without stable shelter because this organization is face-to-face with these people every day.

For example, The Connecting Ground’s street census estimates that there are nearly 850 people living in motel rooms.

Love explained that this number is initially based on the number of extended-stay motel rooms in Springfield that rent to locals. These motels are almost always full, Love said.

Love explained that when a member of the outreach team talks to someone who is staying in a motel, the member makes note of how many people are in the motel room and updates the street census count. And considering there are no doubt more than one person in many of these rooms, sometimes even entire families in one room, that 850 statistic is a conservative estimate, Love said.

CPO, on the other hand, follows the strict HUD criteria and considers only those people who are staying in motels but cannot pay themselves (and meet all the other HUD criteria and have updated with CPO within the last 90 days) as homeless.

How many individuals or households who qualify as homeless in a motel using HUD standards is essentially impossible to know for sure. CPO has issued about 100 motel vouchers so far this fiscal year, but other groups and churches often step up and help pay someone’s motel bill.

Another reason CPO’s numbers are so different from the Connecting Grounds’ street census numbers is that individuals and households “fall off” CPO’s prioritization list after 90 days unless the person comes to One Door to update their information. People fall off the Connecting Grounds’ street census after a year has gone by and the person hasn’t been seen or heard from.

Are McKinney-Vento numbers a reliable measure?

The number of McKinney-Vento-eligible students is another example of how attempting to “count” homeless people can be nuanced and tricky.

The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act is intended to close the achievement gap for students who are unstably housed. If a student qualifies, they have flexibility in which schools they attend and are provided transportation and additional education services. (Learn more about Springfield Public Schools McKinney-Vento program here.)

Families qualify for McKinney-Vento if they are living in any of the following:

- In a shelter

- In a motel or campground due to the lack of an alternative adequate accommodation

- In a car, park, abandoned building, or bus or train station

- Doubled up with other people due to loss of housing or economic hardship

But some of those living situations described above might not feel like what most people think of as homeless.

And the number of McKinney-Vento-qualified students in Springfield Public Schools doesn’t seem to reflect the number of literally homeless kids on the streets of Springfield. This current school year, SPS reported having 1,283 McKinney-Vento-qualified students.

Nate Schlueter, with Eden Village and the Gathering Tree, says it’s a shame that kids who are doubled up with family should be forced to take on the “homeless” label in order to receive the additional support and services from the McKinney-Vento Act.

Take a kid living with his mom and her parents for example, Schlueter said.

“That kid should not have to take on the identity of homelessness to get the services,” Schlueter said. “Should he get backpacks, school supplies and free lunches? Absolutely. But he’s very much in a home surrounded by a loving family — in poverty. But that doesn’t mean he’s homeless.

“That is a different level of poverty that (the McKinney-Vento) Act asks people to take on as an identity,” Schlueter continued. “The numbers become very confusing and inflated.”

Garand and Bodendieck agree that the large number of McKinney-Vento students at SPS can add to the confusion about this community’s unsheltered population, but the legislation has wonderful benefits for students living in poverty.

“The nice thing about (McKinney-Vento’s) broadened definition is that it unlocks resources for the youth, and it instantly engages them in educational rights,” Garand said.

“If they went by our constrained definitions, then kiddos wouldn’t have transportation to their home school. They wouldn't have access to immediate education with (proof of) vaccinations, for example.”

Bodendieck added: “The point of the rights under McKinney-Vento is to guarantee that you receive quality education (and) there’s not an interruption due to housing instability.”

The ‘elephant in the room’ — the point-in-time count

It won’t be long before CPO and the Ozarks Alliance to End Homelessness do yet another type of homeless count: the annual HUD-mandated point-in-time (PIT) count. This number will almost certainly be lower than what most believe to be the true number of homeless people.

When talking about the many nuanced definitions of homelessness and confusion around the number of homeless people, Garand called the PIT the “elephant in the room.”

Continuum of Care organizations conduct PIT counts on a single night in January. Last year’s point-in-time count found about 450 individuals who were spending the night in some type of shelter program.

Due to limited staffing, One Door staff was unable to conduct an unsheltered point-in-time count last year. But the Crisis Cold Weather Shelter sites were open on the night the PIT was conducted.

That means many of the individuals who were counted last year as being in emergency shelter programs were really unsheltered homeless people, but it still gives One Door staff a good idea of how many people are out there. But PIT counts are notoriously off and fluctuate wildly on years when they are conducted on bad weather nights.

“If it's raining, cold, icy weather, it actually drives our numbers down because they are not traveling,” Garand said. “People hunker down. It’s just total luck of the draw on point-in-time count.”

Bodendieck agreed.

“It’s not a comprehensive count. No one ever said it was a comprehensive count,” he said. “This is a snapshot at this particular point and we can extrapolate out based on it.”

Pastor relies on ‘street census' numbers — Here's what that means

The Connecting Grounds Church and Outreach group began keeping what Pastor Love calls the “street census” in 2020 when most communities across the country were unable to do the annual point-in-time census due to the pandemic.

“We recognized that it was really important, especially with the impact that COVID was having on data collections and point-in-time count,” Love said, “for us to be gauging the numbers. We started keeping this giant spreadsheet. It’s evolved over the last couple of years. When we first started, we just had names.”

Now the street census has different categories based on where people sleep at night: on the streets/in camps, in vehicles, in motels, staying with friends/family or in shelter/program.

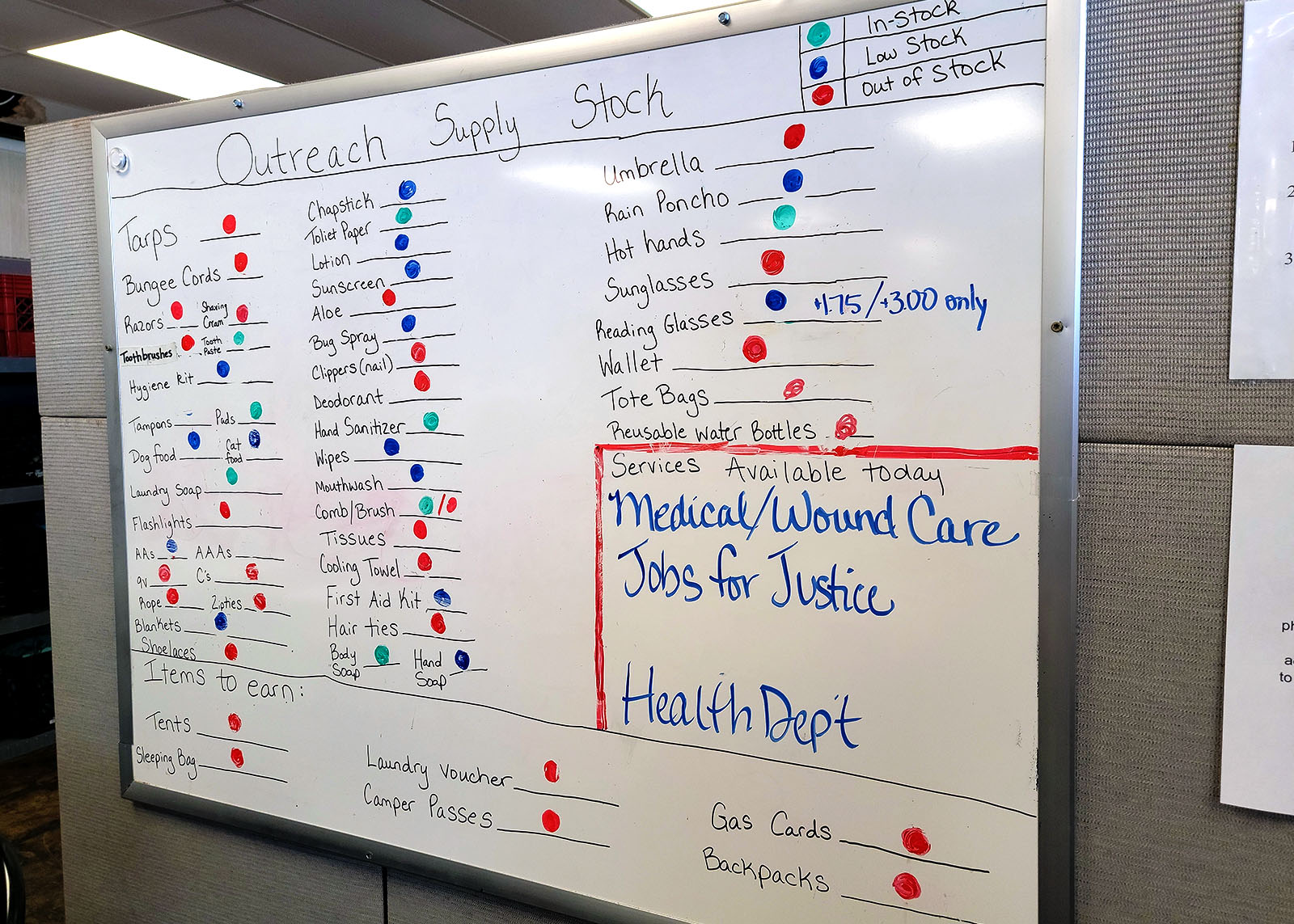

When someone comes into the Outreach Center at 3000 W. Chestnut Expressway or when an outreach team member encounters someone in a camp or on the streets, they are asked where they are sleeping, and that information is updated in the street census.

The Daily Citizen stopped by the Outreach Center last week and found the director Kristi Johnson sitting near the entrance working on the street census (an Excel spreadsheet) on a laptop computer. She showed the reporter how the spreadsheet is updated, but wouldn’t allow any photos of it to protect peoples’ privacy.

Johnson explained when someone comes into the Outreach Center, they are asked about their living situation and their information is updated if needed. She also checks to make sure there are no duplicates and updates the “date of last interaction.”

According to Love, they are adding names more frequently than they are taking them off — but that does happen often.

“There’s a guy today who I know for a fact is getting on a Greyhound bus in 30 minutes,” Love said last week in a phone interview. “So I went in today and took him off the street census. I’ve got a gentleman that I knew was just sentenced to a year in the Department of Corrections. He is off the street census. When people come and say, ‘Hey, I got into housing,’ we immediately pull them off the street census.”

According to the most recent numbers on The Connecting Ground’s website, there are 2,435 homeless people in and around the Springfield area who have engaged with someone from Connecting Grounds’ outreach team within the last year. Of those:

- 785 are living on the streets or in camps

- 140 are living in vehicles

- 849 are living in motels

- 189 are staying with friends or family

- 472 are in a shelter or program

These categories are all situations that HUD defines as homeless, but not necessarily “chronically homeless.”

Love believes the true numbers are actually higher than what the street census reports because it’s “almost impossible” to count all of the people who are living in their vehicles or doubled up with friends and family.

Love, like most who serve the unsheltered community in Springfield, said she understood exactly what population of people the “78 chronically homeless households” in CPO’s Facebook post referred to.

In her view, that number is disproportionately small because it only counts those who are updating their assessment information with One Door every 90 days.

“It’s really difficult, especially if you don’t have a calendar to keep track of when your 90 days are due,” Love said.

It’s also challenging for people to keep coming back every 90 days when there’s no housing or programs available or that they qualify for, Love said.

“It’s frustrating when the waits are just really long, and you don’t feel like you’re making any progress,” she said. “You don’t feel like you’re going to be a candidate for anything.”

Love said she is constantly talking to people about why they must keep going back to One Door every 90 days.

“We’re trying to do a lot of education to help people understand: You have to keep going back,” she said.

Garand, with CPO, acknowledged that it can be deflating for folks who come back every 90 days to update their information but find there still isn’t any housing assistance for them. But it’s important that One Door staff be able to contact someone when their referral for services does happen.

“One of the things we don’t talk about enough is that the system works,” Garand said. “Last year, The Kitchen permanently housed over 400 households. God only knows how many people that is. Those are individuals that were experiencing homelessness, and through the system of care, coordinated entry, wrap-around services and HUD-funded programming, they are no longer homeless.

“That’s a big deal. That is just one. We have Catholic Charities. We have Salvation Army,” she continued. “We have all these different phenomenal agencies that are funded or not funded that are making a big impact on the number — whatever it is.”

Thanks in part to the American Rescue Plan Act, which included funds for emergency housing vouchers, Bodendeick said they’ve been able to get more people into housing than ever before in the past year or so.

“It is really critical right now to get people engaged with the system,” Bodendeick said. “Between the emergency housing vouchers and other opportunities and things that are happening right now, probably 65 to 70 percent of households on our prioritization list have been referred to or are engaged and in the process of determining eligibility and being referred to some sort of supportive housing project.

“That is a much higher number than we’ve ever been able to see. It’s a huge number,” he said. “But that is only serving those who are on that active list, who are engaging in some fashion.”

‘If one person is outside … it should spur us to action’

Nate Schlueter is chief visionary officer for Eden Village, which builds tiny home communities for disabled and chronically homeless people. Even though there are about 250 individuals on the waiting list for a tiny home, Schlueter estimates there are about 580 unsheltered people in Springfield.

“But the reality of the situation is that if one person is outside, as a community, we need to do something about that,” Schlueter said.

“People ask us all the time what the numbers are, and we can drive around our city and see that there’s a problem. And that should be enough to spur us towards compassion.

“I don’t know what the number is, but I don’t feel like I necessarily need to know,” he added. “I see it, and so it should spur us to action.”

How to help

Safe to Sleep is an overnight shelter for homeless women. Find out about volunteer opportunities and a list of items needed on their website or call 417-862-3586.

The Connecting Grounds Church operates an outreach center and team to help the unsheltered community in Springfield. Learn how to help online. Find the Connecting Grounds’ Amazon wish list here.

Springfield’s Crisis Cold Weather Shelter program is in critical need of volunteers this winter. These shelter sites open up on nights when the temperature is going to hit 32 degrees or colder. Learn more about volunteering here.

The Kitchen, Inc. has an emergency shelter for homeless people and several housing-assistance programs. Learn more online.

Victory Mission has limited shelter beds for homeless men, as well as faith-based programs to help them out of homelessness. Learn more online.

Eden Village I and II are tiny home communities for chronically disabled homeless people. They continually need donations and volunteers. Learn more online.

Salvation Army has the Family Enrichment Center for homeless families and Harbor House, a faith-based recovery and shelter program for homeless men. Learn more online.

Gathering Friends is a grassroots group of homeless advocates that serve meals to the homeless. They also help pay for medications, collect donated shoes and clothes and purchase bus passes on occasion. You can join their Facebook group and find ways to help there. Search “Gathering Friends” on Facebook. Find Gathering Friends’ Amazon wish list here.