Why care?

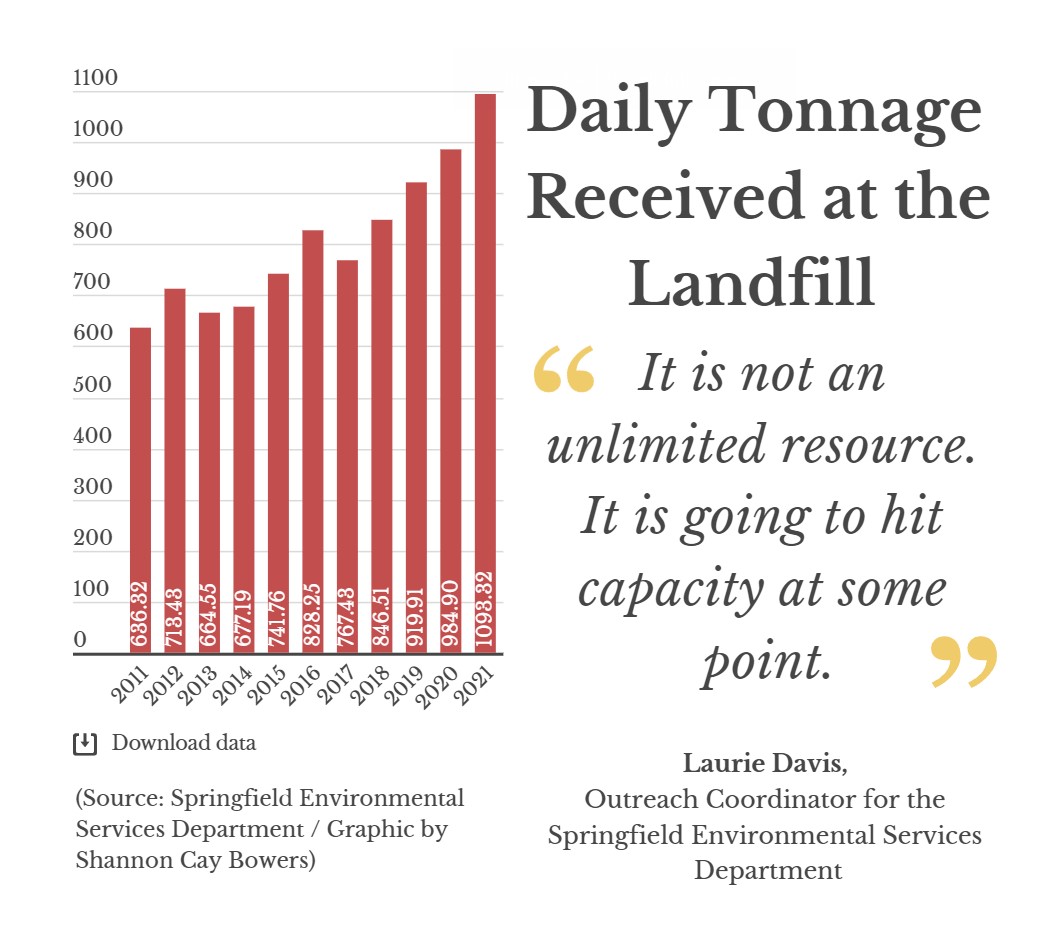

Last year, for the first time since the local landfill opened in 1975, industries and individuals collectively threw away more than 1,000 tons of trash each day, on average. That is shortening the life of the landfill and adding urgency to improved programs for recycling food waste, paper and other materials — an estimated 70 percent of all garbage could be recycled.

Atop a plateau of strategically layered soil and trash at the Noble Hill Sanitary Landfill, there is a machine that looks a bit like a derailed train car. It’s called a tipper, and if you hang out at the landfill for about 20 minutes, odds are you’ll see why it’s called that.

By truck, by trailer and on occasion by Corvette, people from Springfield and the surrounding area haul tons of garbage to the landfill each day. The tipper gets in the action when the big loads arrive. And it’s been getting more use than ever in recent years.

On June 16, a driver backed a waste-hauling semi onto the tipper, disconnected its trailer and drove forward. Then it was tipping time. Slowly, hydraulically, the tipper lifted the trailer from its parallel position with the ground until it was almost perpendicular to the earth. As it began to tilt, a trash bag tumbled out of it. A few bottles, cans and other stray items clanged to the ground alongside it.

But like a nearly empty water cup filled with crushed ice, almost everything inside the trailer held in place as it tipped forward — until all of a sudden none of it did. Out rushed the whole payload.

“So, 30 tons in probably less than 10 seconds,” Laurie Davis, the education outreach coordinator for the city’s Department of Environmental Services, said as vultures swirled overhead and a dozer headed toward the pile to clear space for the next load.

On that mid-June day, people hauled 1,175.95 tons of trash to the landfill that serves Springfield (located near Willard).

“And last week, we had a day where we hit 2,400 tons,” Ashley Krug, sustainability coordinator with the city’s Department of Environmental Services, said at the time.

The landfill — located about nine miles north of Springfield adjacent to Highway 13 — is open 307 days a year, and four-digit tonnage days used to be uncommon. Now, they are average.

Last year, for the first time since the landfill opened in 1975, industries and individuals collectively threw away more than 1,000 tons of trash on average each day — 1,093.32 tons, to be precise. That’s about seven Statues of Liberty tossed every day.

Since it opened, the landfill’s daily average tonnage has tended to tick up by about 3 percent annually, superintendent Erick Roberts said. It had gone up and down in recent years before 2018. Then, from 2018 to 2021, a new high was produced every year.

The above-average surge in waste disposal changes the educated guess on when Springfield’s landfill will reach its capacity, Roberts said, but that number has always been a moving figure.

- In 2017, as the city was considering a nearly $1.9 million, 42-surface acre expansion to the landfill, Roberts said about 13 years remained before it would reach capacity. The expansion, which was approved, promised to add an estimated 53 years to the landfill’s life expectancy.

- In her presentations, Davis tends to ballpark the landfill’s projected closure date at about 75 years from now.

- A recent EPA report, however, pegs the landfill’s projected closing year as 2112, or 90 years from now.

“It is not an unlimited resource,” Davis said. “It is going to hit capacity at some point.”

And opening a new landfill is no small feat for Springfield's future. It would require several hundred acres of land that residents are OK living nearby that's also accessible by a bunch of giant trucks.

Earlier this year, the city tweaked a contract with the Missouri Department of Natural Resources in which it agreed to pay about $16 million to seal off and care for the landfill once it runs out of space.

The document doesn’t offer a predicted date of when that will happen, but it shows they’re preparing for it. And no matter when it’s projected to close, Davis said, our garbage habits should be addressed now.

Economic growth means more trash

What causes people and businesses to truck more trash than ever to the landfill? It’s a question with a lot of possible answers, Roberts said, including at least one positive one.

“That waste, the amount of waste that the community is generating, is a little bit of an economic indicator as to how much activity is happening in and around your community,” Roberts said.

More trash tends to mean more growth. Indeed, economists have in recent years found a strong correlation between the GDP and the number of freight cars carrying waste across the country. They call it the garbage indicator.

In the Springfield area, Roberts said, “you still can hardly find anybody in the construction industry who’s not booked out several weeks or months.” The byproducts of all that development pile up in the landfill. That’s a part of the story, Roberts said, but not the whole one.

“It would be difficult to pin it on one contributing factor,” Roberts said. “There are some conversations across the industry that say the pandemic played a role in that because, for a period of time, people were home, people were really focused on cleaning and disposal, and cleaning out their garages, and cleaning up their homes. And masks and PPE certainly were flowing through — not just Springfield — but across the world. Those things were flowing through communities at a much higher rate than anytime that we could probably remember in our lifetimes.”

If you’re looking to Springfield’s landfill for signs of a recession, there aren’t many there. In Springfield’s case, economic belt-tightening briefly heaped more trash on the scales. Krug said this summer’s soaring gas prices led the area’s larger waste removal companies to temporarily reroute their trucks to the city landfill rather than driving to private landfills further away. The fuel costs outweighed the tipping fees at the city facility, she said.

The trash flow has remained in the thousand-ton-a-day range during the 2022 fiscal year, Roberts said, with preliminary figures pointing to a slight decrease from last year.

And somewhere in the neighborhood of three-quarters of it could have been recycled before it reached its final, compacted resting place.

Up to 75 percent of waste sent to landfills could be recycled

The most recent EPA data says Americans generated about 294 million tons of waste in 2018 — the most the agency has recorded in one year — and about half of it was landfilled while the other tons were either recycled, composted or combusted. Of the 148 tons that went to the landfill, roughly 75 percent of that could have been recycled.

Local estimates are based partially on national figures, as well as on a recent gloved hands-on study. On Sept. 21, 2016, and then again on May 23, 2017, consultants working with the Missouri Department of Natural Resources visited the landfill and dug through a few tons of your trash. They spent another two days in March of 2017 eyeballing the hauls of construction, demolition and industrial crews that trucked waste to the landfill.

“They pull aside trash trucks coming into the landfill and they take all of their waste and they hand-sort it,” Krug said. “I know, right? What a fun job.”

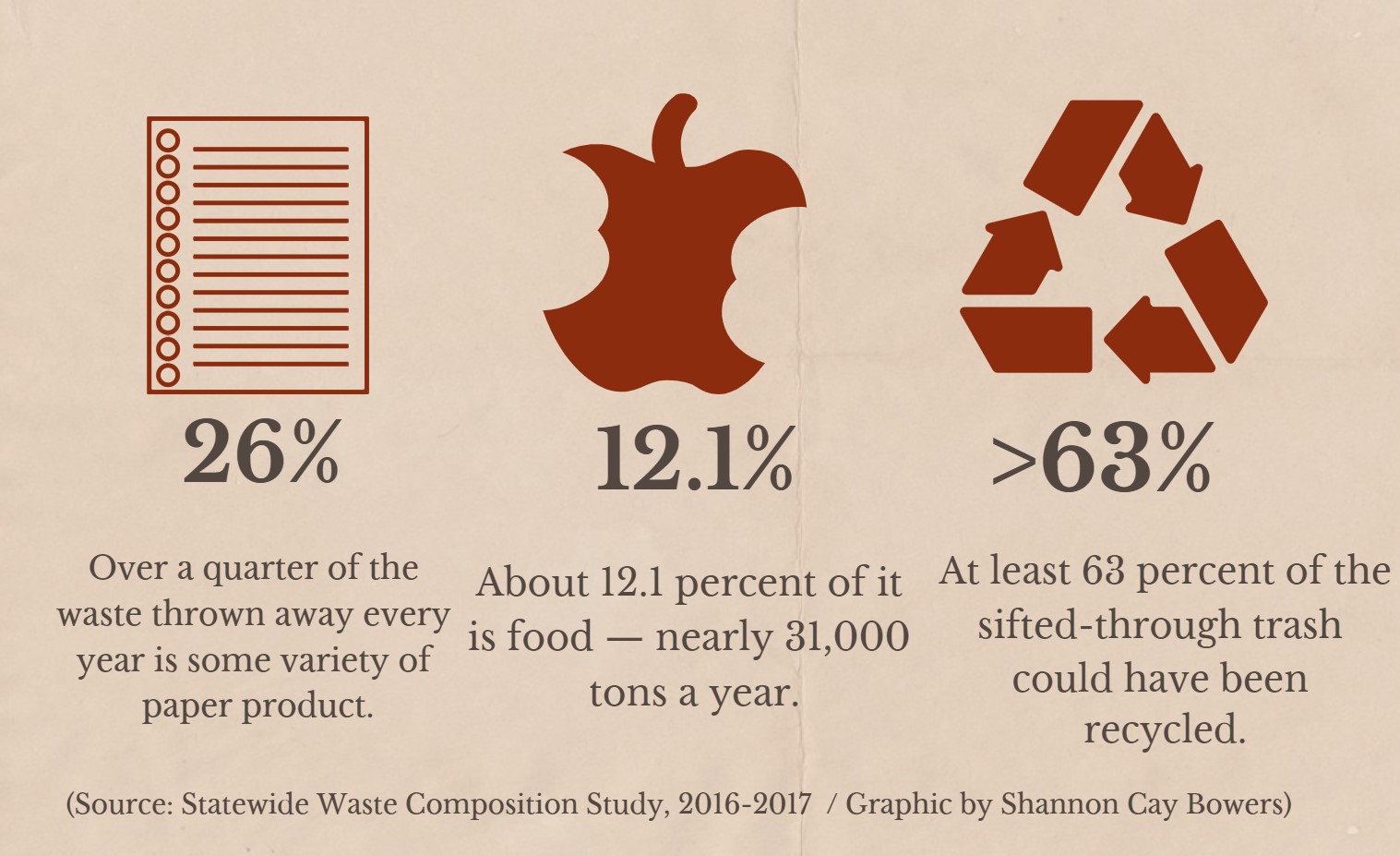

What they found during those trash pulls, along with the visual observations made during the March 2017 visits, gave a detailed snapshot of what Springfieldians jettisoned back then. The numbers show:

- Over a quarter of the waste thrown away every year is some variety of paper product.

- About 12.1 percent of it is food — nearly 31,000 tons a year.

Those measurements are before the recent, steep climb to over a thousand tons of trash per day.

The study estimated 63 percent of the sifted-through trash could have been recycled. Krug said she ballparks the amount of recyclable Springfield landfill tonnage around 70 percent, in-between the national numbers and the local snapshot.

Those numbers told her we have got to stop throwing away so much food.

Food for thought

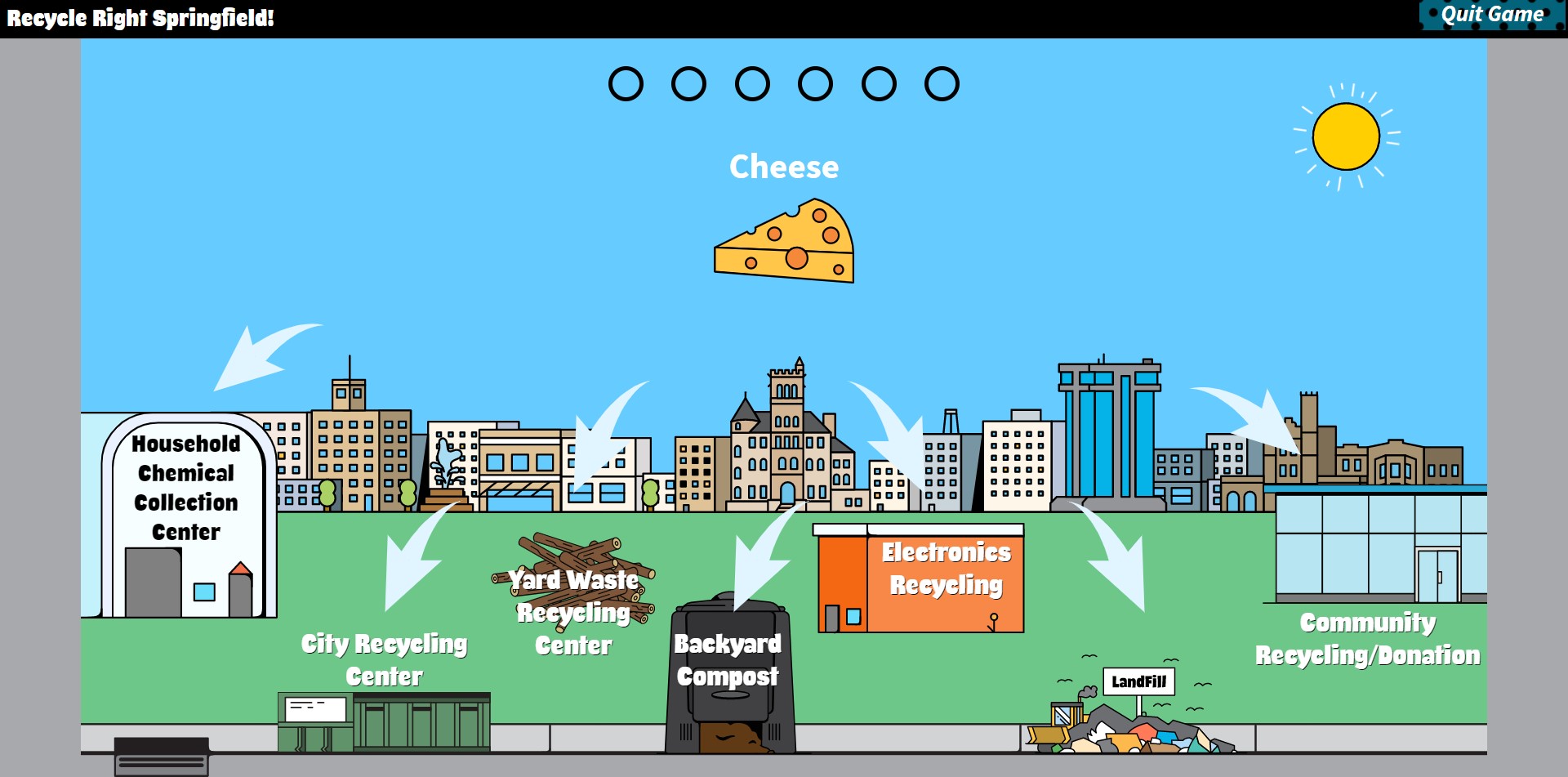

There is a recycling game on the Environmental Services website that shows all of the city’s waste disposal and recycling options. When you play it, an item materializes above the city skyline, and you click it and drag it to the right place to throw it away. Wine bottles and toilet paper rolls go to city recycling centers. A broken TV goes to an electronics recycling center. An old slice of pizza? Right now, that gets dragged and dropped into the landfill.

“The landfill is the last place that needs to be and frankly the last place a lot of things need to be,” Krug said. “The amount of food that comes here is stupid.”

Around the same time the state released its Springfield landfill food waste estimate, Krug said the EPA put a spotlight on how heavily food waste contributes to greenhouse gas emissions. Krug said the confluence of events made it obvious to focus on improving the situation in Springfield.

For residents, options are currently limited. The nonprofit Springfield Compost Collective picks up food waste from businesses and homes for a fee and offers community compost bins in three neighborhoods. Krug continues to lead the expansion of the city’s Dish to Dirt home composting program, which provides applicants with free indoor and outdoor compost bins, and a class on how to convert waste into compost.

She said the program started with Environmental Services accepting a $4,000 grant from Ozark Headwaters Recycling and Materials Management District and then investing about $12,000 into the program. In city terms, Krug said, it might not seem like a lot of money, but it was a big investment in terms of outreach.

“We are funding it completely out of the solid waste fund right now on our own, and citizens aren't having to pay anything,” she said. “And that was really important to us, is that we were giving them the tools to do something and not asking them to pay us for it.”

So far, Krug said, there are about 400 bins out in communities, and a few hundred people on the waiting list to take the class and get involved.

Krug has worked with numerous local businesses to divert food waste to food banks and ag producers, and the city currently has an exemption from the Missouri Department of Natural Resources to work with businesses on a case-by-case basis to compost at the yard waste recycling center.

Right now, some of the main products in the city composter are pre-consumer goods like excess fried onion flecks from the local French’s factory and tea bags from the Hiland Dairy plant. She has recently been researching a USDA grant that could lead to a pilot program that might encourage more city composting. In the near future, the city is going to unveil a restaurant compost program.

Right now, Krug said, she spends a lot of her time talking with food industry leaders to learn what the barriers to composting are, and giving presentations at businesses across the city that are centered around reducing food waste, and improving that 31,000-ton problem at the landfill.

“Reducing the amount of food that we are individually wasting is a pretty easy problem to get our arms around,” Krug said. “And that's just not the same with climate change. That's just not the same even with recycling, to a point. It's a hard thing for some people to get their arms around. But being like, ‘I will only eat four bananas, so I'm not going to buy 20 bananas' — that's something we all can do.”

Dish to Dirt Newsletter

Whether you want to apply for a city-provided compost bin or not, you can subscribe to the Department of Environmental Services Dish to Dirt newsletter, which offers seasonal tips on soil care, composting and recipes designed to address excess produce. You can sign up here.

‘Let’s just be thoughtful from the beginning’

A big message that Davis, at the city, tells her audiences is they are getting some of this right. Over 10,000 tons of diapers go to the landfill every year, according to 2017 figures. And that’s exactly where they belong, Davis said.

Discarded in another environment, they could be extremely hazardous, she said. But the landfill’s base is built to trap putrescible waste — the “quick gross” kind of trash, Krug said. It keeps trash juice, or leachate, from seeping into the groundwater supply and is engineered to repurpose some of the methane produced during decomposition. Currently, captured methane is used to electrify about 2,000 Springfield homes and power a greenhouse on the landfill acreage.

Another message they relay is that we’re all going to get some of this wrong.

“Right now, I have a 2-year-old who has decided today he hates strawberries, and I've ruined his life by giving them to him,” Krug said. “I am very, very aware of how much food is wasted in my own home, and we have to have that conversation and talk to people about how we get it. It's challenging, and it's frustrating. We just want to equip you with the tools to do the best that you can with it, understanding that we're not perfect, and no one is going to be perfect. It's why we have all these other resources — including the landfill — because we aren't perfect. Let's just be thoughtful from the beginning.”

To drive home that much of what ends up at the Springfield landfill could have gone elsewhere, Davis and Krug bring all kinds of tour groups to the landfill to walk around, see it, smell it and give people some agency in the life of their landfill.

Depending on the weather conditions, they try to get groups as close to the current cell where trash is being dumped and compacted by heavy machinery that runs over it at least three times before burying it beneath a layer of soil. It may look chaotic, Roberts said, but it’s an orchestrated process. He compared it to an endless game of Tetris. Getting people to see that firsthand has been a department priority since 2019, Davis said recently during a presentation.

This summer, she led a field trip of first graders to the landfill, and as the bus pulled up to the base of the trash heap, something caught the class’ attention. It was a child’s bike that looked brand new, she said.

“The kids were like, ‘somebody put a bike there!’” Davis said. “Yup, and that bike is going to have to stay there, and at the end of the day, the compactor will run it over and it will not look like a bike anymore.”

Telling kids that a perfectly good bike is going to get smushed because someone threw it in the landfill is the kind of message the outreach team hopes resonates with them.

“When we all feel that sense of ownership, we're going to be more careful with it,” Krug said. “That's the impetus of a lot of the work that we're doing right now in environmental services in general. If we can get more people in the river, will that improve our water quality? Because you care about the river they play in. So that's why we bring people to the landfill. When you come to the landfill and you see how much trash is here, you go home and say: ‘Oh. I’ve got to do a better job.’”

How can I be better at recycling in Springfield?

Recycling is an ever-evolving endeavor and the items that are and aren’t accepted at different Springfield facilities change. The Department of Environmental Services created a way to help people figure out who takes what. It’s called the Waste Wizard.

The service shows both public and private locations to dispose of throw-away items in an effort to minimize landfill waste. Searching for “plastic bag,” for instance, returns results for several thrift stores that reuse them and several Walmart stores that collect them to ship to recycling centers. The more generic you type in a search, the better it tends to guide you.

Try “battery” as opposed to “hoverboard” or “massage gun,” for example, and you’ll find a place to take products that have rechargeable lithium batteries. Roberts implores people to dispose of those properly because they can combust and start trash fires if a compactor runs over them the wrong way.

RELATED STORY

A guide for environmentally conscious Springfieldians — what options are there?

“Greening” your lifestyle is finding ways to make your spending, eating and consumption habits more environmentally friendly. Finding the right resources to green your lifestyle can be daunting, but Springfield has many low-cost options.