IN-DEPTH|

Elijah Speer was 19 when he got busted with about half an ounce of psilocybin a few years ago. Psilocybin is an illegal substance better known as magic mushrooms.

While Speer described the amount of the drug he was carrying as being “enough to have a party but not enough to be a kingpin or anything,” Missouri law sees it more seriously.

Speer was charged with possession of psilocybin, a class D felony punishable by up to seven years in prison or one year in the county jail with a fine of up to $10,000.

Does a 19-year-old with no serious criminal history and about $100 worth of mushrooms truly deserve to spend time in prison?

A Greene County judge thought not, and recommended Speer be screened for the drug treatment court program as part of Speer’s probation. Judges do not order defendants to complete treatment court. Instead, they are screened to see if they are appropriate for the program.

Greene County’s Adult Treatment Court is an at least 18-month-long intensive program that serves as an alternative to costly jail incarceration. The treatment court program requires defendants in felony cases to submit to frequent and random urine analysis, have stable housing and employment, attend substance use disorder classes and attend court on a regular basis.

No quick fixes in treatment court

“I tell my people here that, ‘You know, you didn’t get in here overnight. You’re not going to get out of here overnight,’” said Commissioner Kevin Austin, who presides over Greene County’s Treatment Court programs.

The mission is to enhance public safety by reducing criminal activity associated with substance abuse and addiction. Non-violent felony offenders are placed into a judicially supervised program that provides comprehensive treatment, life skills training, and accountability for behavior — which helps offenders become sober, law-abiding members of the community.

Greene County has treatment court programs for offenders convicted of drug-related crimes, driving while intoxicated, those with co-occurring disorders and a treatment court for veterans. Greene County also has a family treatment court program to serve the best interests of children whose parent(s) are dealing with substance use disorder.

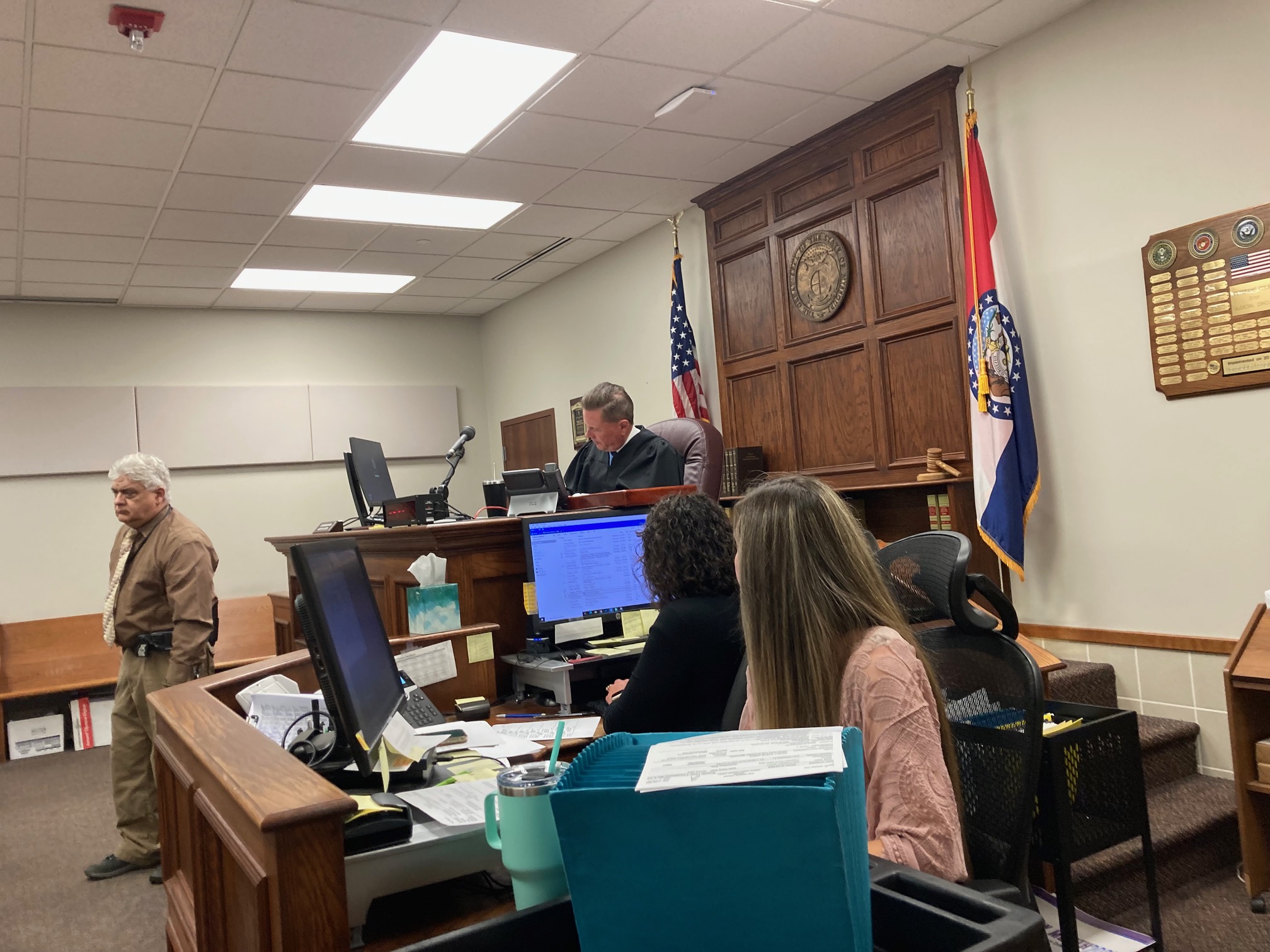

When participants appear in treatment court — which is housed in the third floor of the Greene County courthouse alongside the other courtrooms — they discuss their progress and/or challenges with not only the commissioner (judge), but their treatment providers, their probation/parole officers, counselors or mental health care providers and anyone involved in the participant’s treatment program.

This “team approach” is an effective way to hold people accountable for their actions or inactions, said Alon Fisch, founder and CEO of New Beginning Sanctuary, a faith-based sober living and substance use treatment program.

New Beginning staff members are often part of the treatment court team, because one of the main requirements to graduate from the program is to have stable and sober housing.

“Treatment court has a whole team looking at you,” Fisch said. “You’ve got counseling. You’ve got housing. We all work together with [the Missouri Division of] Probation and Parole. And it’s very difficult to fake it, let’s put it that way. They (participants) have to actually put in the work. And there is a lot of work.

“The more the community integrates and works together, the better,” Fisch said. “When we work as a team, we get a lot more done. There’s a lot less manipulation. There’s a lot less lying and cheating and working through the system. We love the relationship we have with the treatment court.”

‘Treatment court is not easy’

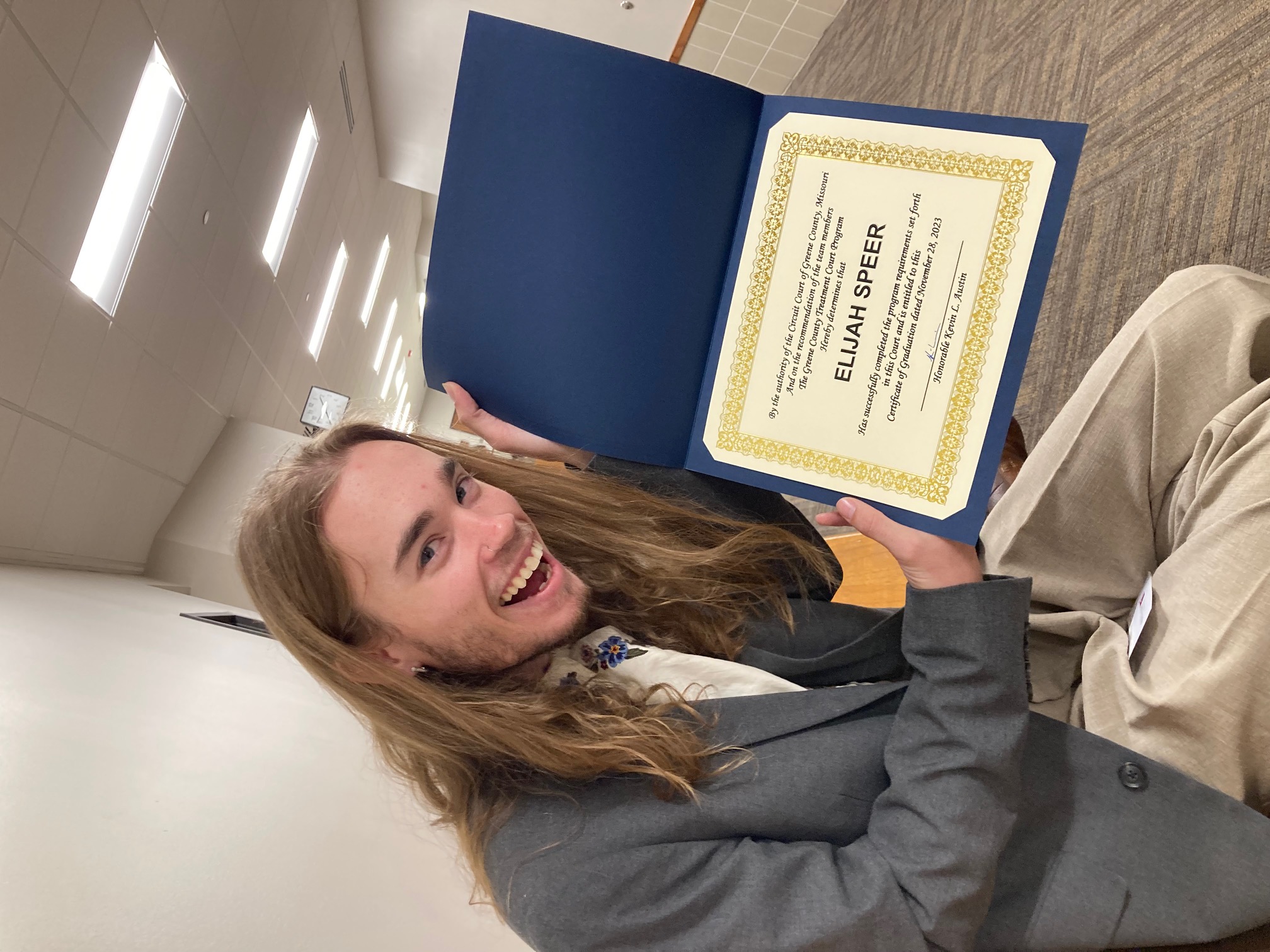

Speer graduated from Greene County’s treatment program in late November 2023, and spoke to the Hauxeda as he exited the courthouse. Treatment court staff protect the privacy of participants while they are in the program. Following his graduation, Speer said he was happy to share about his experience.

Speer made it clear the program is not a “get out of jail free” pass.

“Treatment court is not easy,” Speer said. “It’s not.”

Speer’s stint in treatment court was somewhat unusual in that he wasn’t physically dependent on mushrooms. Physical addiction risks with psilocybin are low. In fact, new research points to the possibility for psilocybin to be used to treat substance use disorders.

But just as anyone ordered to treatment court, Speer had to complete all the required drug treatment classes, weekly urine analyses and court appearances.

Speer once missed a treatment class because he was busy moving. Though he thought it wasn’t a big deal at the time, Speer had to spend the night in the Greene County Jail.

“That was awful,” Speer said. “That was the most dehumanizing experience of my entire life.”

Speer said he learned a lot about addiction, hardships and life in general.

“There were a couple of times when friends of people in class overdosed and died,” Speer said. “It was, like, raw.”

Other times, a friend from class would stop coming and he’d never see them again.

“You’d be like, ‘Where'd they go?'” he said. “And it’s like, ‘Oh, they relapsed. They’re in jail.’ You just see everybody’s battles.

“You get to hear the good stories, too,” Speer continued. “The good stories of, you know, ‘I was addicted to methamphetamine for 15 years. I lost my kids. I got into this treatment court. I’m getting my kids back. My life is on track.’

“It’s definitely a good thing,” Speer said of the treatment court program. “It helped a lot of people.”

Data shows graduates less likely to reoffend

Since Missouri’s first treatment court was created in Jackson County 30 years ago, the programs have evolved and expanded throughout the state. At this time, there are no national standards defining how to determine recidivism rates for treatment court participants.

But in 2017, the state of Missouri examined cohorts of people admitted into adult drug treatment court and DWI court programs and tracked whether or not they graduated or were terminated from the program and whether they had been convicted of a new charge within the next three years.

Of those who successfully completed a drug treatment court program, 4.5% had a new plea or finding of guilt within a year. Compare that to those who were terminated from the program who had a 9.9% rate of a new plea or finding of guilt.

Of those who successfully completed a DWI court program, 2% had a new plea or finding of guilt within a year. Of those who were terminated from a DWI court program, 5% had a new plea or finding of guilt within a year.

Nationally, researchers with Stanford University found drug court programs reduce drug use and re-arrest for non-violent, drug-involved offenders. Because they are resource-intensive, drug courts may better be reserved for more complex cases in which the individual has not responded to less resource-intensive supervision.

According to one study cited by the Stanford University publication, offenders who were assigned to treatment court were two-thirds less likely to be re-arrested compared with individuals under typical supervision. Another study found that recidivism drops, on average, by 38 to 50 percent among adult drug court participants.

Fisch, with New Beginning Sanctuary, considers the treatment courts program a “great alternative” to prison or jail.

“It’s an opportunity for somebody to change their life, turn it around and get one more shot before being sent away,” Fisch said. “The amount of supervision they get depending on their needs is very important.

“It doesn’t overcrowd the prisons and it actually targets the problem,” Fisch continued. “There’s just not as much help for drug treatment in prison. And once you are in prison, I don’t know how much you are going to be seeking (treatment) out. Whereas here, you have to do it in order to complete it.”

Commissioner enjoys watching comradeship form

Back when he was a practicing attorney and treatment courts were a relatively new thing, Austin said he viewed the program as a “get out of jail free card; a kinder, gentler place to do probation.”

“I clearly have come to think otherwise. Treatment court is not the ‘kinder, gentler’ place to do it,” he said. “They do a lot of heavy lifting. I mean, they have every week court, probation officer appointments, home visits from the probation officer. They have multiple treatment classes.”

Offenders must also pay $2,500 in treatment court costs to complete the program, and they are usually assigned at least 200 hours of community service as part of their probation.

“We have several goals in mind. Public safety is one. Having good citizens is another,” Austin said. “But also, helping that particular person have a sober and happy life.”

For Austin, one of the neatest things about treatment court is watching the comradeship and support form between participants.

“Everybody’s in here together and everybody hears them come up and talk to me,” the commissioner said. “And they hear the treatment providers and the prosecuting attorney and the probation officer all talking.

“Some courts are closer units than others,” he said. “Veterans (court) is the closest, as far as close knit. These guys are involved in each other’s lives. These guys are supportive of each other.”

Austin clarified that female veterans are often ordered to veterans court as well. In fact, veterans court is the only program that is co-ed, Austin said. Men and women are separated in the drug court, DWI court and co-occurring.

“We have enough problems with people dating people they should not be dating already,” Austin said. “And we talk about stuff that’s embarrassing, you know. They talk about stuff that maybe they wouldn’t want the females to hear and vice versa.”

Learn more about Greene County’s Treatment Court programs at greenecountycourts.org/treatment-court.