IN-DEPTH |

Part of a series on domestic violence in Springfield and Greene County. Need help? See related story.

People found guilty of domestic assault in Greene County often are placed on probation with one of the conditions being they attend a batterers intervention class instead of going to jail or prison.

Prosecutors routinely agree to send defendants to the classes. Defense attorneys claim victory when it happens. Judges oblige — off to batterers class you go.

Yet, despite a sea of good intentions, no one in Greene County has compiled hard data that could determine if these programs actually reduce domestic violence.

- No one apparently carefully tracks how many perpetrators complete the class, or how many face consequences from a judge if they drop out or don’t attend regularly.

- Nobody knows how frequently convicted perpetrators are required to repeat the class.

- Nobody knows if those who attend are less likely to reoffend.

- No one can say if these classes fundamentally change the culture surrounding domestic violence by interrupting the dynamics of power and control at play. And local batterers class instructors make little effort to collaborate with the people and agencies that deal directly with victims. (See related story.)

The Missouri Department of Corrections and its Division of Probation and Parole said, in response to a Sunshine Law request, they do not have any statistics or analysis of batterers programs. In addition, the department refused to allow local employees involved in the program to be interviewed by the Hauxeda.

Local prosecutors, judges, lawyers, parole officials, and advocates who fight domestic violence and judges acknowledged they have no Greene County completion or recidivism data, despite the fact the courts routinely use these programs, which are paid for by offenders.

“That would be helpful,” said Dan Patterson, Greene County prosecuting attorney. In seeking to hold domestic violence perpetrators accountable, Patterson said: “I have to look at the tools I have in the toolbox. Batterers classes are one of the tools.”

I have to look at the tools I have in the toolbox. Batterers classes are one of the tools.

Dan patterson, Greene county prosecuting attorney

- Part I: Black eye for Greene Co.

- Part II: Obstacles to leaving

- Part III: Systemic issues

- Part IV: Searching for solutions

Why care?

Domestic violence is a black eye for Springfield and Greene County. It is an everyday occurrence and affects thousands of lives every year. Yet a major obstacle to addressing it is that many people still don’t believe it’s widespread or much of an issue.

System not designed for victims, can be difficult for them to endure

The lack of accountability for measuring the effectiveness and the impact of this common sentencing tool is part of our innocent-until-proven-guilty system that can be difficult for victims to understand or endure.

“The system is designed to make it hard to get a conviction against someone because that protects us all from abuse of government power. It was not primarily designed to make it easier on a victim or survivor,” said Greene County Prosecutor Emily Shook, who heads the domestic violence unit.

In the third part of a four-part investigative series, the Daily Citizen explores some of the shortcomings of a justice system where the process is often slow and deliberate, rather than delivering swift and certain consequences for domestic violence perpetrators. (See summary of Parts I and II.)

The Daily Citizen found:

- Laws are challenging for prosecutors to navigate. In interpreting the facts of the case and state law, the most frequent charge filed by local prosecutors in domestic assault cases is a misdemeanor, the least serious of four potential domestic assault charges. Some survivors and advocates say that reinforces the belief of abusers that the conflict was never a big deal in the first place.

- Penalties are often light. For example, of misdemeanor cases from 2022 tracked by the Daily Citizen and resolved as of May 26, about 40 percent of convictions resulted in a suspended execution of sentence, meaning the abuser does not go to jail if they abide by probation rules.

- Too often, the system — including use of orders of protection and the electronic monitoring of perpetrators released on bond — cannot keep victims safe from abusers, and that sometimes has deadly consequences.

A prime example of cracks in the system is the often-prescribed batterers intervention program, which has been governed since 2015 by the Missouri Department of Corrections Division of Probation and Parole.

State sets standards for batterers intervention programs (click to expand)

According to rules provided by the Missouri Division of Probation and Parole, any curriculum for a batterers program must include the following elements:

- What a person gains from being abusive

- The importance of accepting responsibility for abusive/violent actions and behaviors

- Cooperative and non-abusive forms of communication

- Various forms of abuse — so as to not minimize non-physically abusive behaviors

- Tactics of power and control. Identification of tactics shall include isolation, emotional abuse, economic abuse, use of children, use of privilege, intimidation and covert/overt threats

- Equality and power-sharing in relationships. Identification of relationship skills shall include respect, trust, support, honesty, accountability, economic partnership, negotiation, fairness, and responsible parenting

- Long- and short-term effects of violence on partners and children. Exercises shall build empathy to understand the perspective of survivors

- Equal partnerships, respect, responsibility, empathy and understanding of the negative effects and cost of the abuse on survivors, families and others

- Cultural and social influences that contribute to abusive behavior. This should include methods that stress culture is not an excuse or justification for abuse; and

- Non-violence planning, which includes identification of danger signs of negative behavior choices and how to prevent them.

The guidelines also say classes must exclude certain kinds of information, including:

- Techniques or diagnoses that suggest survivors have some responsibility for the abuse. An example would be identifying abuse as resulting from “victim psychopathology,” “victim behavior,” “victim provocation,” or “learned helplessness”

- Techniques that encourage the expression of rage, such as punching pillows and primal screams

- Anger management techniques that place primary causality on anger and/or the sole intervention rather than one part of a comprehensive approach

- Theories or techniques that identify poor impulse control or substance abuse as the primary cause of the violence

No tracking, no cooperation from state agency that oversees batterers programs

While lawmakers years ago ordered Probation and Parole to oversee batterers programs, they did not require the agency to compile big-picture aggregate numbers on course completion rates and recidivism.

Karen Pojmann, communications director for the Department of Corrections, told the Daily Citizen she was not going to “compel” employees to talk to a reporter, “particularly about programs that the department doesn’t manage.”

The department credentials the batterers programs, creates the guidelines for them and also is supposed to annually audit them.

Pojmann said the department could not cite a study or research paper that looked at the effectiveness of such programs but wrote via email that other sources probably could cite examples.

In contrast to the approach to tracking outcomes of batterers intervention programs, the state of Missouri carefully tracks whether drunk drivers complete classes required due to their offense.

Debra Walker, public affairs director for the Department of Mental Health, said that in 2022 there were 16,793 drivers ordered to take the Substance Awareness Traffic Offender Program designed for DWI offenders. Of those, 4,707 had taken the class before, or 28 percent. The data is gathered as part of the program’s objective to reduce the number of DWI re-offenders in Missouri.

Information about the batterers intervention program, if gathered and analyzed, could shed light on the plague of domestic violence in the Ozarks, where victims are beaten and abused daily. The city of Springfield, for example, statistically is the domestic violence capital of Missouri.

If the Department of Corrections had allowed interviews requested by the Daily Citizen, local sources might have been able to explain what burdens, if any, tracking overall data might place on Probation and Parole and why — when creating rules for batterers programs — the division did not require course providers to report course-completion rates.

The information might even indicate which batterers programs work best.

The general assumption is that they work for a few batterers

“We have no statistics,” said Greene County Associate Circuit Judge Margaret Palmietto. “That’s one of those things that is hard to know. If people don’t reoffend, you are assuming it’s effective.”

That appears to be the general assumption.

The Missouri Coalition Against Domestic Violence and Assault compiled a “best practices” report in 2018 for those who run batterers classes. The authors stated, without citing data:

“The limited information resulting from research and practice in batterer intervention demonstrates that, in general, completing batterer intervention is related to a reduction in domestic violence and other arrests.”

Prosecutor Shook said: “What I know from what I have been trained is that in general — not Missouri specific, but in general — batterers intervention programs are considered to be successful with a small number of people … for the people it helps — it helps a lot, but there are a lot of people that it doesn't necessarily help.”

She supports their use.

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

RELATED STORY

Instructor tells batterers they can change how they view relationships: ‘You are capable of being good’

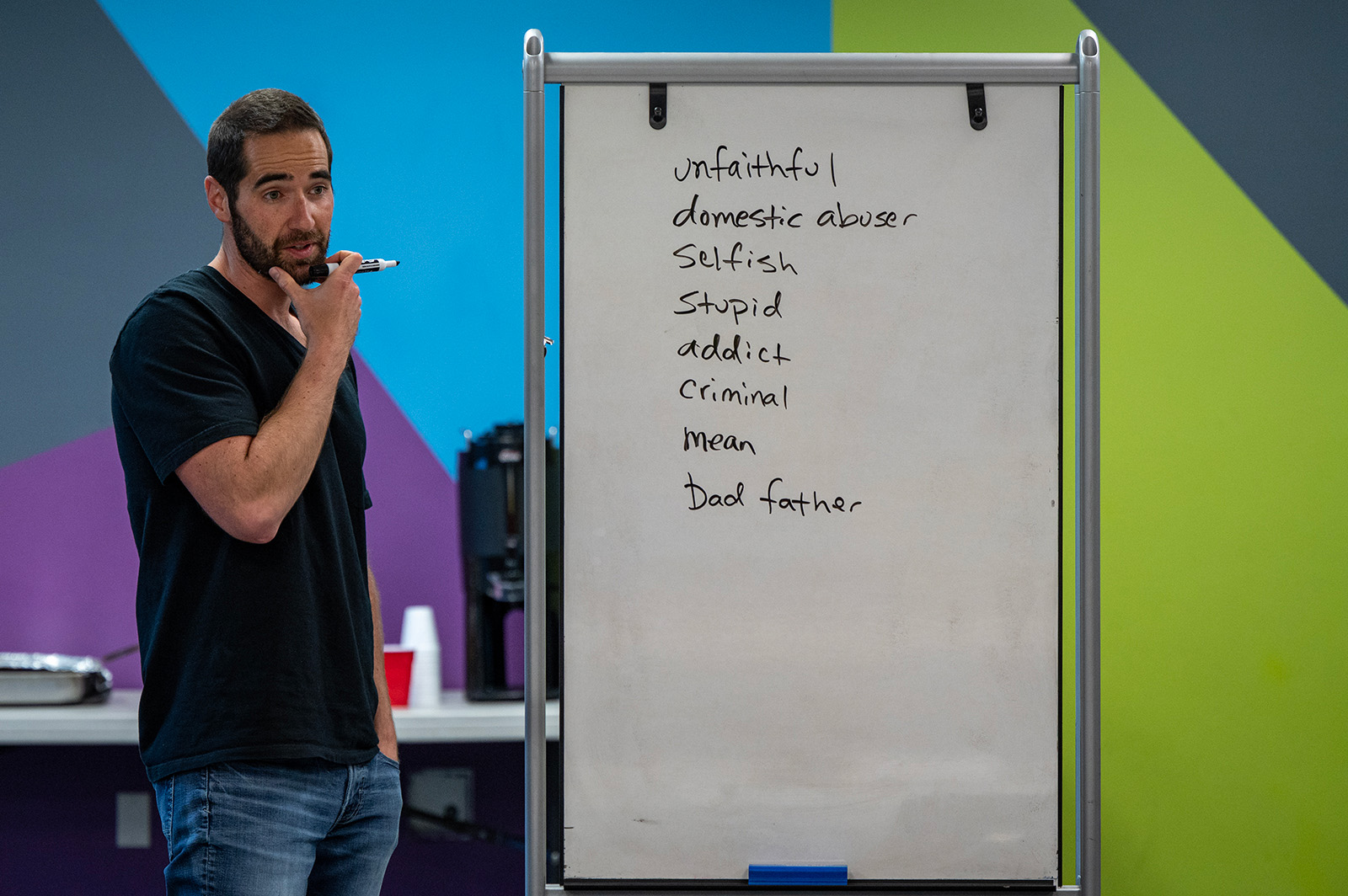

Austin Boon's task is formidable: it is to lead a group of men to a fundamental change in how they view their relationships with women — by meeting 90 minutes a week for 26 weeks.

Review of 5 studies suggests slight reduction in re-offense for those who complete class

For this story, the Daily Citizen was unable to find a Missouri-specific study of the success of batterers classes. But it did find a 2004 review published in the Clinical Psychology Review looking at five separate studies that tracked — using similar but not identical parameters — whether batterers programs reduce the rate of re-offense.

The review came to the following conclusion:

“Treated batterers have a 40 percent chance of being successfully nonviolent, and without treatment, men have a 35 percent chance of maintaining nonviolence. Thus, there is a 5 percent increase in success rate attributable to treatment.

“To a clinician, this means that a woman is 5 percent less likely to be re-assaulted by a man who was arrested, sanctioned, and went to a batterers program than by a man who was simply arrested and sanctioned.”

California auditor found ‘systemic failures’ in tracking those who attend batterers classes

The California state auditor studied batterers classes in five counties, including Los Angeles, and came to the conclusion they are deeply flawed, according to an October 2022 Associated Press story:

“Nearly half of California domestic violence offenders failed to complete a required program designed to prevent future assaults and judges failed to impose new sanctions almost every time,” the story said.

The state has 58 counties. Classes are weekly for a year and generally last two hours. The story continued:

“(California) Auditors found that nearly half did not complete them. County probation departments did not report more than half the violations to the courts. And the courts did not impose any additional punishment to enforce the requirement in 90 percent of the cases where judges were told of the violations.

“As a result of what auditors called long-running ‘systemic failures,' the requirement ‘had limited impact in reducing domestic violence,' Acting California State Auditor Michael Tilden said.

“Auditors found in tracking a sample of 100 offenders: Nearly two-thirds of program dropouts went on to commit new domestic violence or other abuse-related crimes. By contrast, 20 percent of offenders who completed the program committed new crimes.”

Completion rate 63 percent for local class; Daily Citizen request was first time he’d been asked for numbers

Counselor Austin Boon is in his ninth year teaching batterers classes. On April 24, two Daily Citizen reporters and a photographer attended a session where five men were in the class. Boon’s program is called Stop Domestic Violence.

Boon provided the Daily Citizen with data back to 2015. He has had 449 men attend; 63 percent successfully completed the 26-week class and 37 percent did not.

(In Missouri, these classes must be at least 26 weeks, once a week, minimum 90 minutes. They have to be segregated by gender.)

The batterers classes are exclusively funded by the batterers themselves. The operators are independent contractors. Boon, for example, receives $25 from each participant per class.

Boon said he does not know how many of those 449 men who attended his classes re-offended.

He also said the Daily Citizen was the first to ever ask for data on completion rates.

When a participant fails or drops out of batterers class, those who lead the class report it to Probation and Parole, which then should notify the sentencing judge, who might then send the offender to jail or prison.

Mark Powell, who was a Greene County associate circuit judge when interviewed for this story, but subsequently has retired, said that, yes, he is informed when this happens.

“Yes, absolutely. That is a violation of probation.”

Does it result in the defendant going to jail or prison?

Maybe.

“As it is a condition of probation, which is common in these cases, the judge should be notified,” Judge Palmietto said. “The prosecutor will also file a Motion to Revoke the defendant's probation.

“Depending on the case and how the defendant is doing otherwise with probation, the judge could revoke the defendant's probation and execute the jail sentence, or the judge could continue the probation or re-set the probation violation and extend the time allowed for the defendant to complete the class,” Palmietto said.

Better communication skills not the ultimate goal of batterers classes

Counselor Dean Miller for years has offered batterers classes for men and women. His program is called 180 Degrees.

He said that only once before had he been asked for data on completion rates. He recalls that it was not Probation and Parole asking, but might have been someone working on a doctoral dissertation.

Although Miller said he would try to compile completion-rate data for the Daily Citizen, he had not by the time this story was published and is under no apparent requirement to do so. He did not respond to follow-up attempts to reach him.

What you're talking about is a lifetime of learned and practiced behavior on behalf of the offender ... So an eight-week or a 12-week class is not going to fix that.

dan patterson

Terri Perry is executive director of the Community Alternative Sentencing Program. The nonprofit was created in 1985 by Greene County judges and others to oversee defendants sentenced to community service.

In 1992, the nonprofit's mission was expanded to include probation services for those convicted of lesser crimes, including misdemeanor domestic assault. As a result, the organization orders batterers to classes.

Perry said she does not know how many complete those classes and that no one had ever before asked her for data. She said she is unable to pull out data specifically for batterers.

“I do not have any numbers for you. It is just like anything else. It depends on the offender and their outlook.

“There is always going to be those people where no kind of program is going to help them. I do see a lot of people that go through the batterers intervention program and they are very grateful that they were given the opportunity to do the class.

“A lot of them say that they should offer this class to everybody coming out of high school just to help in their relationships.”

But improving communication skills and relationships is not the goal of batterers classes. The objective is to hold offenders accountable.

Even if the classes help abusers achieve greater personal insight via group therapy, do they end the pattern of power-and-control in domestic violence?

“What you're talking about is a lifetime of learned and practiced behavior on behalf of the offender,” prosecutor Patterson said. “So an eight-week or a 12-week class is not going to fix that. There has to be a constant message that this is wrong. And it's not acceptable. That can be through monitoring, that can be through going to jail, that can be through going to prison or being on probation.”

Programs that focus on anger won’t work for batterers

Jamie Willis, director of the Greene County Family Justice Center, said batterers classes are of little or no help if the focus is on treating the abuser's anger issues.

(The Division of Probation and Parole has guidelines for curricula. The classes “may” include “behavior modification/anger management techniques.” But anger management cannot be taught as the root cause of domestic violence.)

“Domestic violence is a demonstrated cycle of violence where there are multiple tactics of control and power that are all held together by violence,” Willis said.

“These people are not angry. This is a control tactic,” Willis said.

“It’s not just losing your cool in the heat of an argument,” Shook added. “And that's one of the reasons why when you look at batterers intervention programs, they're so distinct from marriage counseling or couples counseling. In fact, couples counseling is highly discouraged in abuse situations. Because in couples therapy, the goal is to help these two people relate better to one another.

“That's not the problem in an abuse dynamic,” Shook said. “The problem is that the abuser wants to control the victim.”

About Living in Fear

This special investigative report explores the far-reaching and insidious nature of domestic abuse in our community. Living in Fear is being presented in four parts over two months:

- Part I: Black eye for Greene County, which was published May 8-11, looks at the depth and breadth of the problem here.

- Part II: Obstacles to leaving, published May 22-25, examines the dynamics and complications facing victims looking to leave abusive relationships.

- Part III: Systemic issues, published this week, puts a focus on the criminal justice system and potential shortcomings.

- Part IV: Searching for solutions, to be published in late June, taps local, regional and national experts in search of ways to improve the system and reduce domestic violence.

Next in the Living in Fear series: A murder-suicide from 2018 is case study in how the system is unable to keep domestic violence victims safe.