PERSPECTIVE |

Part of a series on domestic violence in Springfield and Greene County. Need help? See related story.

“I don’t plan on seeing my birthday,” he angrily said to his victim — his wife — on a recent jail visit. “I’m ready. I’m at peace with that. I sent my mother the message last night telling her the six names. Those are the six (pallbearers) I want carrying me.”

He demanded to know what she told the probation officer who asked her if she would feel safe if he’s released from custody.

The man told her the address he planned to give the probation officer if she doesn’t agree to let him come back home: a cemetery.

He then looked squarely into the eyes of the woman he had beaten, strangled, headbutted and sprayed with hot and cold water.

He just stared — wide-eyed, menacing, threatening — without blinking or moving for a full minute.

Visits with Greene County inmates are no longer in person. Instead, people visit with inmates via video-call from their homes. The videos are recorded, and in this case, the prosecution played a few at the man’s sentencing hearing on May 5.

That’s how I also found myself on the business end of his intimidating stare, watching as he pressured his victim to say he could come back home.

His repeated threats of suicide, manipulation, gaslighting, lies and controlling tactics were difficult to take even though they weren’t directed at me, a reporter there to observe how domestic assault cases are handled within the courts.

I sat in the front row and felt terrified for the victim just a few feet away from me.

She came to court, not to give a victim’s impact statement or testify against her abuser. She was there, kids in tow, to show support for him.

At that moment, I wasn’t sure if he’d be released on probation or not. No one knew.

I fully understood why that woman did not want to cooperate with prosecutors.

I get it.

Victims are likely afraid for their lives, for their children’s lives. They know if they leave, their abuser will get shared custody of the children. Their abuser, often someone they love, might be threatening to kill themselves. Their family and friends might be pressuring them, too. They may depend on their abuser financially and emotionally. Their abuser might have them convinced they will never find someone else, they are too stupid or ugly to ever find love again.

I get it.

‘Uncooperative’ ignores the nuance of victim decisions about whether to testify

The prosecutor for this case, John McCaskill, told me later he doesn’t like to use phrases like “uncooperative” when talking about victims who don’t want to testify.

“‘Cooperate,’ I think, is a bad term, and it’s one that we use as well. But I don’t particularly like it,” McCaskill said. “It puts basically all of the pressure on that person to say, ‘Well, this is either going because of you or not.’

“And cooperate, it’s such a wide range of what that means to a person,” he continued. “Somebody can be perfectly cooperative in the sense that they will show up to court and speak at the hearings, but maybe they say, ‘I only want treatment for this person. I’m not going to be the one that’s sending them to prison.’

“Or they may be cooperative in the sense that they are wanting to seek services,” he said, “but will not go into court to face that person because of the fear that’s involved.”

This case was unusual for prosecutors because there was enough independent evidence of the assault the state was able to proceed without the victim’s testimony.

And it was unusual for me, as a journalist, because I just happened to be in the courtroom when the videos were played. I got to look into the man’s eyes, seeing and hearing exactly what his victim did during those video jail visits.

I was rattled for a few days after the hearing.

It’s one thing to spend months interviewing survivors and experts about the dynamics of domestic violence for the Hauxeda's Living in Fear project. It’s quite another to look into the eyes of someone who desperately employs every abusive tactic he can to maintain control over and terrorize his victim.

So please, as you read the stories in this second installment of Living in Fear, keep in mind victims often have very valid reasons for staying in abusive relationships and for not cooperating with law enforcement and prosecutors.

If the victim doesn’t want to testify, why prosecute?

“This case checked what I consider every red flag for lethality,” McCaskill said after the hearing. “You have somebody with a well-documented exorbitant history of threats. This is a choking case. Choking is the highest predictor for lethal domestic violence that we have. There’s firearms involved. He has a prior history with firearms. And just the brutality of this assault.”

According to the probable cause statement from January 2022, the woman walked to the police station in the middle of a snowy night wearing only a towel. She had a cut above her right eyebrow that was bleeding down her face. Her lip was swollen and hair dripping wet.

The video from inside the police station was played at the sentencing hearing. An officer asked her what happened to her forehead.

“He started beating the crap out of me and headbutting me and choking me,” the woman said, her voice shaking from the cold and from the assault.

You don’t know what the judge is going to do, the judge could hear what you have to say and still give him probation.

prosecutor john mccaskill

The Sixth Amendment guarantees a defendant the right to confront witnesses in court. Statements made outside of court are generally considered hearsay and not admissible. But “excited utterances” can be an exception to the hearsay rule.

An excited utterance is a spontaneous statement relating to a startling event or condition, made while the person was still under the stress of excitement caused by it.

At a hearing in September 2022, a Greene County judge ruled that a portion of the video in which the victim first explained to the officer why she was bleeding, wet and wearing only a towel was an “excited utterance” and could be used as evidence in this case.

That video, along with photographs of her injuries, his injuries (he had a gaping wound to his forehead where he headbutted her), blood splatter in the home and firearms in the house (he was already a convicted felon and not allowed to possess guns) were used as evidence against him.

It’s incredibly difficult to prosecute domestic assaults when the victim doesn’t cooperate.

Yet, prosecutors say victims refuse to cooperate in up to 80 percent of the cases.

It’s a complicated issue a lot of people don’t understand, McCaskill said.

“If you are cooperative with us and you don’t know what the judge is going to do, the judge could hear what you have to say and still give him probation,” McCaskill said. “If you were to go to the judge and say, ‘I want this man locked up forever’ or whatever you might say, but there’s that threat in the back of your mind — what if the judge doesn’t, and he gets back out and I just said that? And now he’s gonna kill me.’

“How can you put yourself in that situation? No wonder victims are uncooperative,” he said. “They know their safety better than we do. So when people are like, ‘Victims are uncooperative’ and ‘I don’t understand why she wouldn’t show up (to court)’ I get it. What it would take to be cooperative is more than I can deal with. I’d be like, ‘I want to run away and them not find me again.’”

Jail visit video echoes event that led to arrest

Prosecutors played at least three videos during the sentencing hearing.

Perhaps one of the most disturbing moments, for me, happened during a jail visit video in which a toddler boy could be seen crawling on his mom’s lap while she talked on the video. The boy appeared happy and just being playful.

The man chastised his wife for not disciplining the toddler. The man told her over and over that she shouldn’t let the child get away with whatever the child was doing. He suggested to the woman to spray the child with cold water.

“Use that cold shower,” he said, with a gleam in his eye. “That works so much better with him than whipping his ass. … for dad to snatch him up, take him in there and lay him down and turn the cold water on. How many times did he do that and how long did it take before he was potty trained?”

When this portion of the video played in court, I remember thinking: What is happening? The man seems happy when he talks about this. Did he really just say he potty trained that poor child by spraying him with cold water?

Then McCaskill pointed out to the courtroom something I didn’t notice because I was focused on the defendant.

As the man talked about spraying the child with cold water, the victim began to cry in the video. One of the many ways the man had abused the woman was by spraying her with cold or hot water.

Hearing him talk about doing that to the child must have been a painful trigger for her.

Judge denies probation, sends him to prison

The man was charged with two counts of first-degree domestic assault, two counts of third-degree domestic assault, kidnapping and two charges of unlawful possession of a weapon (all felonies). He entered Alford pleas on all charges, meaning he accepted a guilty verdict without actually admitting to committing the crimes.

The defense attorney argued the man was a good provider for his family and protected his family.

The man stood up and said he was sorry for “severe physical and emotional injuries” to his family. He told the judge he wanted to “come home and rebuild connections” with his wife and children as a “provider, teacher, friend and lover.”

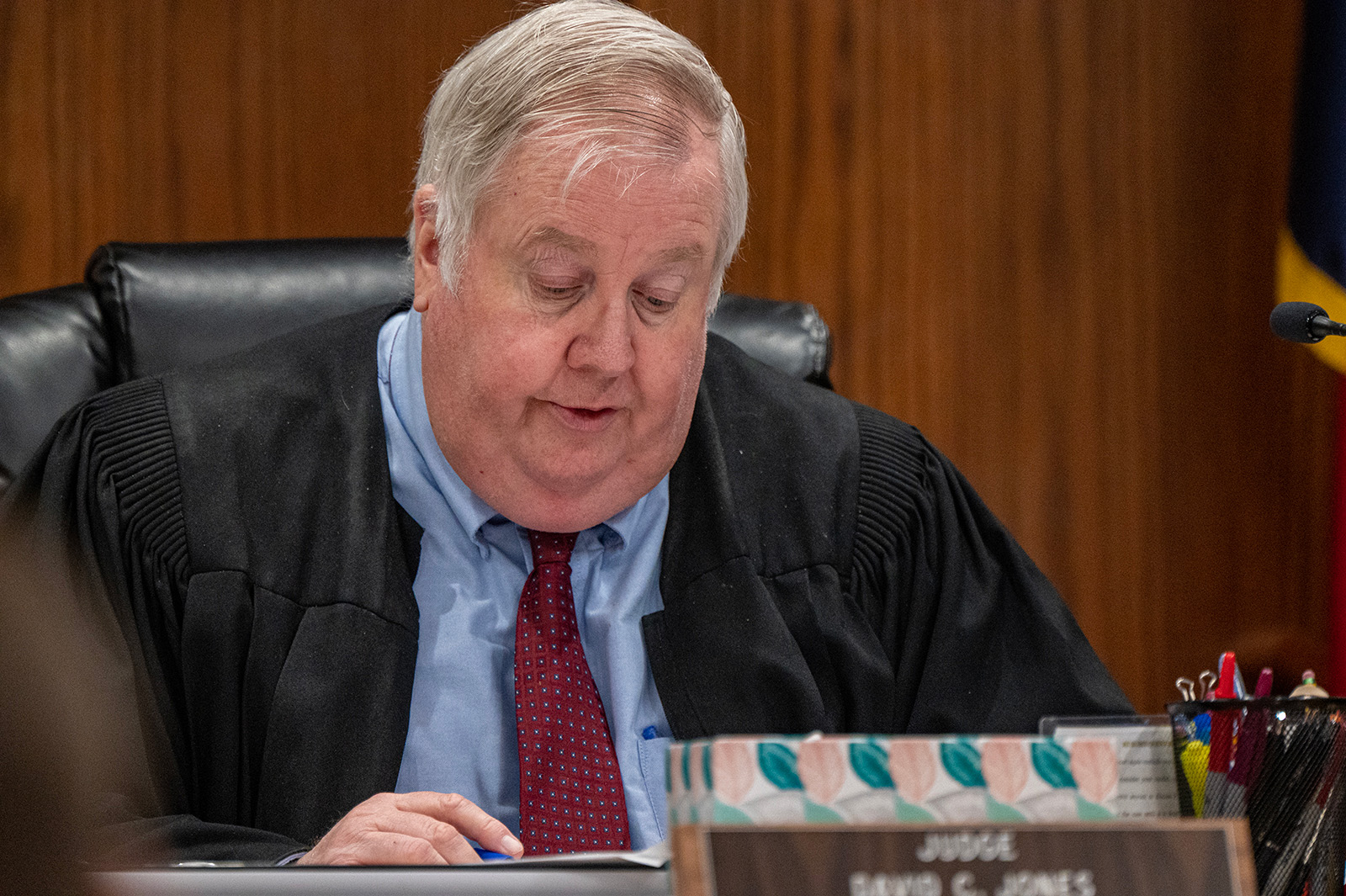

Judge David Jones denied the man’s request for probation and sentenced him to serve 12 years in prison.

I’m not identifying the man who was sentenced on May 5 because sharing his name would essentially identify the victim, his wife. He’s done awful things to her, and I hope she and her children are able to heal now that he is headed to prison.