IN-DEPTH

For many traveling to and from Springfield, short-term rental units — marketed on platforms like Airbnb and VRBO — are a go-to lodging option.

When Stephanie Reid and Derrick Durbin first entered the short-term rental industry after Reid’s retirement from teaching in 2021, it was a huge success. Over the course of the last couple of years, they have grown their small short-term rental business to four properties. Some units they converted from previous long-term rentals, which they still have a few of, allowing their upkeep to essentially become Reid’s full-time job.

They list their rentals on VRBO, as well as Airbnb, which they said makes up a narrow majority of their bookings.

Business, however, has not kept up. At the beginning of the summer, the occupancy rates of their short-term rentals alarmingly dipped and, while other factors could’ve contributed to that, they suggest that the proliferation of unlicensed short-term rentals in Springfield shoulder much of the blame.

While short-term rentals (or STRs) have been legalized and regulated in Springfield since 2019, many owners have flown under the city government’s radar by never acquiring a short-term rental license and/or operating a unit when it may violate city codes.

Up until now, the city has primarily regulated the industry with complaint-based enforcement. However, since Springfield voters enacted a room tax, which consolidated three lodging taxes and added short-term rentals, the city is looking to up the ante of enforcement of short-term rental laws through other means.

Short-term rental owners frustrated with unlicensed counterparts

Reid and Durbin aren’t alone in experiencing a decline in occupancy rates of their short-term rentals. While the amount of available and booked listings continue to increase in Springfield, occupancy rates between June 2022 and May 2023 and the 12 months prior dipped to 58 percent from 68 percent, according to AirDNA data provided by the Springfield Convention and Visitors Bureau.

While they have been fortunate to keep some of their short-term rentals filled over the course of the summer thanks to some guests who stayed for long periods of time, one persistently vacant rental remains a cause for concern.

This may come as a relief to many legally operating rental owners in Springfield, who have undergone the required processes to get their licenses, but have lost business to those who operate without licenses.

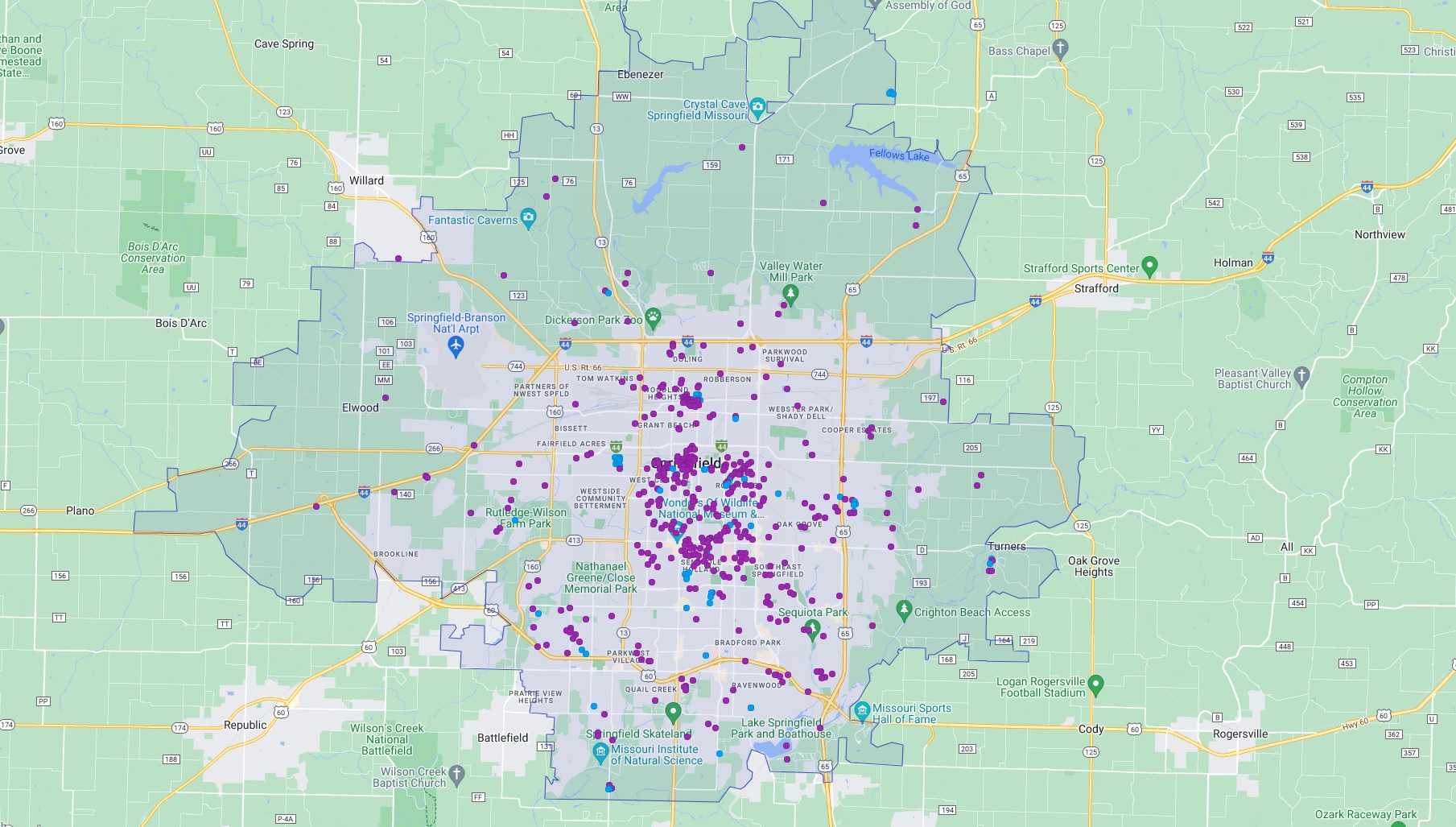

As of August 2023, Springfield is home to 504 short-term rentals, according to AirDNA, a Denver-based software company that compiles and analyzes short-term rental data. The Springfield Convention and Visitors Bureau (CVB) uses AirDNA to collect data to provide reports on the city’s tourism industry.

Granted, AirDNA’s Springfield boundaries are not the exact same as the city limits, but the vast majority of the 504 short-term rentals on the AirDNA map fall within the city of Springfield. However, only about 270 of them are licensed with the city, according to Springfield senior planner Daniel Neal.

Of Springfield’s 504 rentals, 68 percent are listed on Airbnb, 9 percent on VRBO and 23 percent are listed on both apps, according to AirDNA.

Springfield categorizes short-term rentals into three types

The Springfield Code of Ordinances categorizes three different types of short-term rentals: types 1, 2 and 3.

Type 1 short-term rentals can only be in single-family residential and residential townhouse zoned districts. They must primarily be an owner-occupied residence and can only be rented for periods of less than 30 days at a time, and no more than 95 days in a calendar year if the owner isn’t there. However, there is no limit to the number of rentals if the owner is on the premises the entire time the unit is being rented. If the owner — or other guests — are present, Airbnb lists these rentals as “private rooms.”

Type 1 owners are required to obtain a business license and an affidavit to certify that the residence or accessory dwelling unit will not be rented out for more than 95 days a year.

Type 2, the most common type of short-term rental in Springfield, are also required to be in single-family residential and residential townhouse zoning and can be rented for no more than 30 consecutive days. Unlike Type 1, Type 2 rentals are not owner-occupied residences. In addition, Type 2 rentals in Springfield are limited to one per blockface — one side of a city block between two intersections — of eight residential structures, and none are allowed on a blockface with less than four residential structures, unless approved by the City Council on an appeal.

“The density limitations at the time didn't seem like they were going to be very limiting,” Neal said. “But over time, I think it just depends on what area you're in on how many there are, how popular it is to try to purchase a house and fix it up and try to use it as a short-term rental.”

The acquisition of a Type 2 short-term rental license begins by the owner paying a $350 application fee. The applicant is then required to hold a neighborhood meeting and notify all property owners within 500 feet of the proposed short-term rental and the president of the property’s neighborhood association.

The applicant is then required to submit a summary of the meeting and a notarized affidavit with signatures from at least 55 percent of adjacent residential property owners. If they are unable to collect a sufficient amount of signatures, they can then appeal to the City Council.

In addition to a short-term rental Type 2 application, applicants are required to obtain an annual business license and a certificate of occupancy. In total, the process to acquire a Type 2 license can take anywhere from 6 to 12 weeks, and potentially longer if the City Council must pass a resolution granting the permit.

Of the 270 licensed short-term rentals in Springfield, approximately 180 are Type 2, according to Neal.

Lastly, Type 3 rentals are not located in single-family or residential townhouse zoning, but can only be rented for a period of less than 30 days, like Type 1 and Type 2. Type 3 owners are required to obtain a business license and a certificate of occupancy.

Each type of short-term rental has a host of other requirements that can be found in the city code.

New lodging tax made debut July 1, spurred CVB focus on industry

On April 4, Springfield voters approved Question 3 with 66 percent of the vote, which consolidated three lodging taxes into one, totaling a 5-percent rate. Springfield began taxing short-term rentals, which were previously not taxed under the hotel/motel tax, at the same rate.

The new tax went into effect on July 1. Prior to that, on June 26, the Springfield City Council voted on how the tax revenues would be spent:

- 47 percent, estimated to amount to $3,358,500, to the CVB to promote travel and tourism. The CVB will receive an additional 44 percent once debt for Jordan Valley Park is retired;

- 4.5 percent, estimated to amount to $322,500, to the Springfield Regional Arts Council to support arts and cultural tourism in the community;

- 4.5 percent, also estimated at $322,500, to the Greater Springfield Area Sports Commission to promote the attraction of sporting events in the community.

When tourism executive Mark Hecquet first took over as head of the CVB in January, following the retirement of long-time president Tracy Kimberlin, the organization had done some initial research about short-term rentals. Short-term rentals were not tracked with the same depth as Springfield’s hotel market.

“In light of April's decision at the ballot, we thought it was obviously prudent now, in light of what we do as an organization, to start tracking the short-term rentals,” Hecquet said.

Hecquet said that, prior to the new lodging tax, they felt challenged to promote the short-term rental industry due to the lack of tax revenue it provided them. Now that short-term rentals — at least, the licensed ones — will be taxed, he said the CVB staff is looking at ways of promoting them.

“It's pretty exciting for us,” Hecquet said.

While the inclusion of short-term rentals under the hotel/motel tax will contribute to an increase in revenue, Hecquet said the CVB hasn’t made any concrete plans on how those funds will be used, and described it as a “don't want to spend it before we get it type of thing.”

Risk of operating without a license

Even as Reid and Durbin followed the legal path to acquire short-term rental licenses, which varied in time length and requirements for each of their properties, they found new short-term rentals crowded the market and the Airbnb listings. Some were licensed and some were unlicensed.

Durbin said the lack of enforcement of short-term rental licenses incentivizes some short-term rental owners to operate illegally, which they said has created, “so much extra competition.” Because of that, they paused any additional investments and started losing money.

“We are struggling with every single property so much that now, I’m thinking, ‘Do we go back to operating as long-term rentals and run that risk?’…But the whole reason we decided to kind of make the shift with some of our properties where tenants were moving out was because of some of the problems we've had [with long-term rentals],” Reid said.

Reid said that she wished short-term rental hosts in Springfield would be required to show proof of license on their listing — in some cities, short-term rental hosts are required to provide a registration number in the description of their rental.

“I keep lowering the rates, and it’s not making a difference…I've just been trying to brainstorm solutions because frankly, I'm kind of in a panic,” she said.

Unlicensed undercutters look for fast money

Johnny Eakins, who is recently retired, is looking to build up a handful of short-term rental properties. Unlike Reid and Durbin, Eakins expanded his search outside of Springfield, looking as far south as Stone County, which has its own vacation rental ordinances.

Eakins plans to primarily buy properties that are already short-term rentals to avoid rolling the dice on whether or not he would be able to acquire a license.

“If you bought a property strictly for that use, and you weren't able to get a permit, then obviously some people are going to go ahead and run it illegally without the permit because, you know, they already purchased this property for that purpose,” Eakins said.

While Eakins said he understands why some hosts might take the easy route and skirt regulations for a short-term cash gain, he sees his properties as long-term investments and didn’t want to be fearful of someday being “shut down because I wasn't paying the correct amount of taxes or didn't have a permit.”

However, Eakins remains concerned how his unlicensed competitors could take away business from him. Those hosts could more easily undercut his prices because they aren’t spending any of their incomes to cover fees and required upkeep. They are avoiding paying the 5-percent lodging tax.

Jeremy Hahn, who owns and operates short-term rentals through Hahn Adventure Co., said he thinks there would be fewer unlicensed short-term rental owners in Springfield if the process to acquire a license was easier.

“To me, it really creates a big ordeal,” Hahn said. “I guess the process now almost makes it seem as though there's suspect activity. It's assumed that there will be suspect activity happening in the home, and that’s not what Airbnb is.”

Hahn appealed to the City Council for a short-term rental license previously, as he was unable to collect the necessary signatures of approval from neighbors.

Hahn, Eakins, Reid and Durbin are among those property owners Hecquet thinks are doing it “the right way,” and is hopeful the new lodging tax will bring about more short-term rental property owners like them in the future.

Not a fan of short-term rentals, Hosmer has sought stricter enforcement

While Springfield City Councilmember Craig Hosmer was in favor of adopting short-term rental regulations in 2019, he was never really in favor of the rentals in the first place. While he said they are less problematic in some areas, Hosmer thinks it becomes an issue when they start multiplying in single-family residential neighborhoods.

In general, Hosmer said it is frustrating when the City Council passes a law, but it is not effectively enforced, putting people who follow the law at an “economic disadvantage.”

“It’s not just the short-term rental issue — there's a lot of issues in the city,” Hosmer said. “Everything's complaint driven, and that, to me, is not a good way to ensure compliance with a lot of laws. If we don't want to enforce them, maybe we should get them off the books.”

In previous City Council meetings, Hosmer has expressed his desire to better enforce short-term rental regulations. He said that desire has driven conversations with city staff in recent months.

Hosmer would like Springfield to become more of a primary enforcement city, where enforcement of laws relies less on complaints.

“You don't want to be complaining about your neighbors because ultimately, it's going to come back that you were the complainant and then that creates even more animosity,” he said.

Short-term rentals a lightning rod when brought before the City Council

Although many short-term rental applications never come before the City Council, they are often discussed at length by council members, as well as the bigger picture of the short-term rental industry in Springfield.

At the Aug. 21 City Council meeting, a short-term rental application came before council members after the applicant was unable to acquire any signatures from the adjacent property owners.

Hosmer, while not directly opposed to the applicant or the specific short-term rental in question, voted against granting the resolution in looking at the bigger picture of the proliferation of short-term rentals in Springfield.

Because the city code allows the City Council’s discretion in allowing a short-term rental permit even when the applicant is unable to collect the required amount of signatures, Councilmember Abe McGull was supportive of the resolution.

“I can’t pick and choose what ordinances we want to follow or not follow, but this is on the books,” McGull said. “I never wanted short-term rentals, I didn’t pass this legislation, but I’m obligated as a city councilman to follow the ordinances that we have on the books.”

Mayor Ken McClure said his process for selecting how he supports short-term rentals was based on the efforts made by the applicant to collect signatures from property owners and what the applicant has to say.

While the City Council ultimately granted the short-term rental application by an 8-1 vote, with only Hosmer opposed, several council members expressed concerns with the process to acquire a license, and an openness for potential modifications.

City hires company for more enforcement effort

Hosmer said that he thinks the adoption of the new hotel/motel tax is prompting the city to take a more “proactive” approach in enforcing short-term rental regulations and license requirements.

Similarly, Hecquet said that the taxing element for short-term rentals gives the city government “teeth” to crack down on unlicensed rentals.

Springfield city staff confirmed that more primary enforcement of short-term rental laws is coming, and that the inclusion of short-term rentals under the lodging tax was a contributing factor.

“Our resources have not increased for this effort, it's just become more of a focus because if you look at it now, it's a double whammy, honestly — if they're not licensed because they're not following the statute for being licensed as a business nor are they paying now the applicable taxes for the lodging tax,” said Quincy Coovert, who works in the Licensing Division in the Finance Department with the City of Springfield.

Thus far, Coovert said that enforcement of Springfield’s short-term rental laws has been on a “pretty much strictly a complaint basis.”

However, city employees are exploring a potential contract with a monitoring platform, which would collect and analyze short-term rental data and provide it to the city to carry out enforcement.

“The city wants to really hire someone with expertise in this space to get them sorted, and then once it's all sorted, they'll run with it,” Hecquet said.

A budget adjustment for the funds to hire a monitoring platform has already been made, according to Coovert. It will not be covered from any of the revenues from the hotel/motel tax, which has already been allocated.

Once the city determines which monitoring company to hire, Coovert said they will send them information on the short-term rentals that are licensed. In turn, the company would compile a list of properties determined to be operating without licenses.

“Then we would reach out to those properties regarding compliance,” she said.

Detection is hard to automate

Coovert said that the process of properly identifying the unlicensed short-term rental owners is very manual, in part because addresses are not provided on marketing platforms like Airbnb until after a booking has been made, and that the city ultimately doesn’t have the resources to carry out this kind of work, hence the need to hire a company.

“The platforms that I've talked to that do this type of work explained how labor intensive it is on their end,” Daniel Neal said. “Obviously, that's why they’re services.”

While she couldn’t give a definitive timeline, Coovert said Springfield staffers hope to have the company they intend to contract with identified soon, so they can share data and allow the third-party company to begin its work later this year.

Initially, the city would mail the unlicensed hosts a letter, notifying them that they need to comply with the code. If the property owners don’t respond or take steps to apply for a license, the short-term rental operators would be fined and a hearing would be held at the Springfield Municipal Court, according to Coovert.

If they don’t meet the requirements laid out in the city code, then they wouldn’t be able to acquire a license, and be forced to end operations of the short-term rental.

Previously unlicensed short-term rental owners who come into compliance with the code will be required to pay back taxes dating to July 1, 2023.

As of July 25, Neal said that the City of Springfield hasn't seen an uptick in unlicensed short-term rentals seeking licenses, despite the lodging tax having gone into effect more than a month ago.