There were more than 100 cases in a single month where someone in Greene County reached a breaking point — a mental health crisis or sense of hopelessness that pushed a person to threaten to harm him/herself or other people.

If that person was you, a family member, a roommate or a close friend, would you know where to go or who to call for help?

Conventional thinking says call the police, take the person to a hospital emergency room, or if it happens in the middle of the night, try to wait until the next morning to get some help.

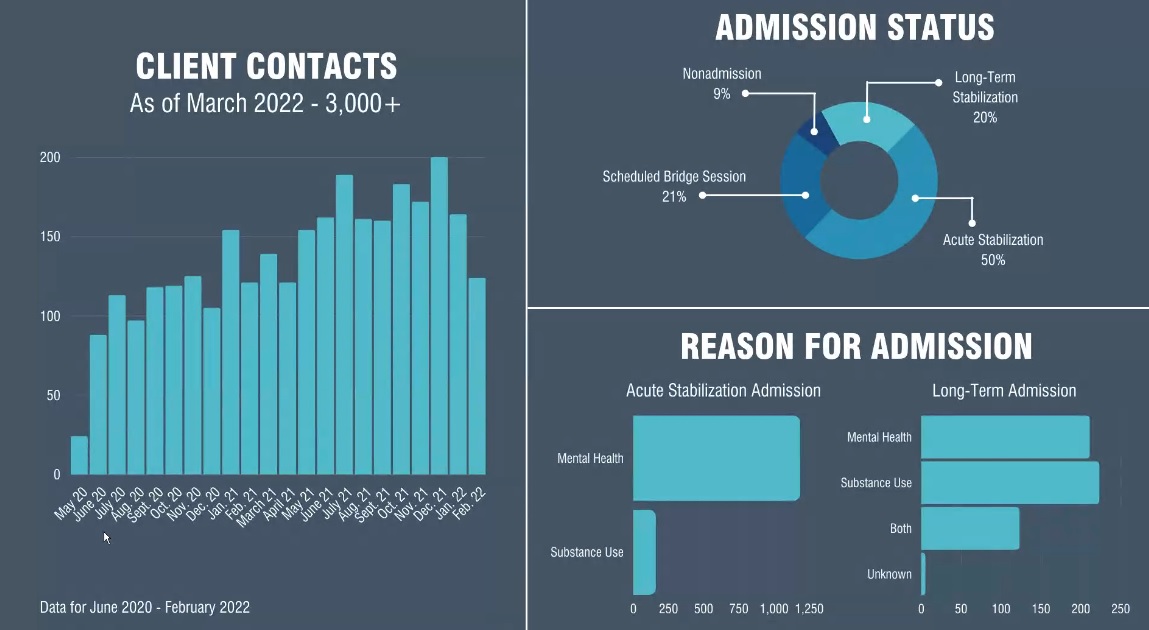

Convention has changed over the past two years in Greene County, where the county government formed a public-private partnership with Burrell Behavioral Health to open a 24-hour crisis center for people in immediate danger of harming themselves or others. Since May 2020, more than 3,000 people have sought help at the Behavioral Crisis Center in Springfield, and Greene County is becoming a model for how a community can respond to mental health crises.

Dustin Brown, vice president of integration for Burrell Behavioral Health, spoke to the Greene County Commission April 28. In February 2020, the Greene County Commission signed a contract to spend $1 million in public funding for the Burrell Behavioral Crisis Center. The walk-in crisis center was the result of an 18-month study of mental health in Greene County. The crisis center is located at 800 South Park Avenue in Springfield, and is a place where people can go for “immediate stabilization” during a mental health or substance abuse crisis where they may threaten to harm themselves or others.

“In March, we were able to hit client No. 3,000, and then we’ve eclipsed that by a couple hundred since that point,” Brown said. “When you look at ramp-up periods and then full-fledged year after numbers for even similar centers, they don’t hit that kind of number that quickly.”

A couple of key goals for the Behavioral Crisis Center are to relieve crowding and wait times in jails and hospital emergency rooms, and to make walk-in mental health services more available to people in Springfield.

“We saw a little bit of a dip in people coming through the door in January and February of this year, and that coincided with the omicron outbreak, which was to be expected. Then we bounced back in March, and it looks like in April we’re even higher than March,” Brown said.

Mental health resources in Springfield

24-hour hotlines

Burrell Crisis Assist Team (417) 761-5555

Harmony House and Victim Center (417) 864-SAFE (7233)

Additional resources

Greene County Family Justice Center (417) 874-2600

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) of southwest Missouri: https://namiswmo.org

NAMI warm line: (417) 864-3676

NAMI Hope Center (peer-operated drop-in center for persons living with mental illness) (417) 864-3027

Mental health service providers are like many employers in Springfield; they feel the effects of a workforce shortage, particularly when it comes to licensed behavioral health providers.

“Twenty-one percent of the people that do come in on a daily basis right now are a scheduled re-appointment or appointment with us, so they have been through the crisis center, they were stabilized, they were discharged home, but there is usually about a 14-21 day wait to get into outpatient services, and when someone is in crisis, we don’t want them to wait that long,” Brown said.

The Rapid Access Unit is a walk-in facility for persons ages 18 and older to access immediate psychiatric care. Clients can get medication-assisted treatment for opioid use, psychiatric assessment, initial assessment eligibility determination, a brief therapy session with a counselor, information on access to peer support services, 23-hour observation, referral to appropriate follow-up treatment and other care as needed.

The public-private partnership is making Greene County a model for responses to mental health crises, and similar efforts are happening in other parts of Missouri based on the Springfield model.

Mental health crisis can happen to anyone

Brown said it’s important for people who fall into some type of mental health crisis to stay engaged with care providers in some way as they shift from a crisis intervention to regular appointments and other health management treatments with a provider.

About half of the people who come through the door at the Burrell Behavioral Crisis Center are there for about 4-6 hours. They receive treatment and intervention, and then go home, Brown said. Another 40 percent of patients are admitted to a mental health facility for longer-term care. Less than 10 percent of the patients are sent to another facility, like a hospital or a jail.

“We have quite a bit of substance use, especially methamphetamine — has been on the rise in the last two years. We’re seeing a lot more of that, which can mimic the mental health symptoms of psychosis,” Brown said.

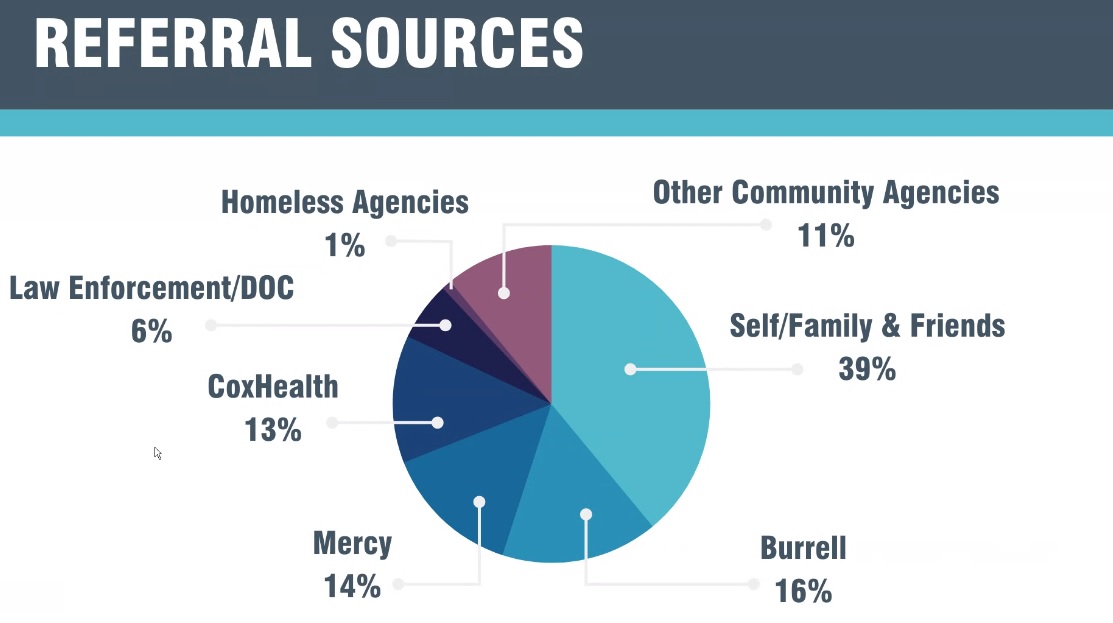

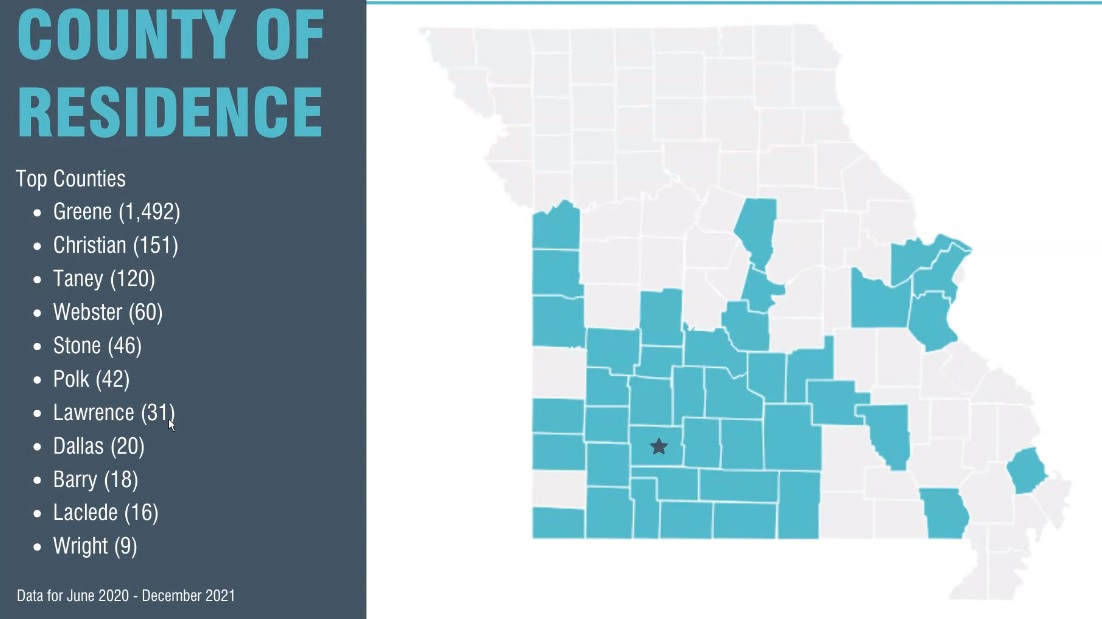

Patients came to Springfield to get crisis help from 40 different counties in the past year. Brown’s report also included a breakdown that showed 39 percent of the patients are self-referred, which means they come in by themselves or come in with a family member on their own accord.

About 16 percent of the clients come to Burrell on a referral from a medical clinic. CoxHealth and Mercy hospitals combine to refer another 27 percent of the patients, with the split about even between the two hospital systems. Six percent of the clients are referred directly by law enforcement agents.

Next step: mobile crisis care

Burrell also received a grant from the Missouri Foundation for Health to create a mobile health crisis unit. Springfield was the only site selected to start such a program.

“We will be able to fund individuals that will ride with our (crisis intervention team) at (the Springfield Police Department) throughout the daytime hours to co-respond with them when there is a mental health issue,” Brown said. “That team will be able to go out to the scene and be able to provide on-site behavioral health counseling and then get that individual to the next level of care.”

During overnight hours, an employee at the Burrell Behavioral Crisis Center will be on call and able to go to calls involving mental health issues if the need escalates to such a point where a counselor on scene could help resolve an issue.

96-hour holds

Missouri law allows a judge or law enforcement agent to involuntarily commit a person to a mental health or inpatient psychiatric facility for 96 hours of evaluation, if the person who signs the affidavit believes the person may harm themself or harm other people.

The mobile crisis response concept piqued the interest of Greene County Sheriff Jim Arnott during the commission meeting. Arnott asked Brown about the possibility of mental health professionals taking on some of the administrative work that comes with 96-hour holds — work Arnott says can keep deputies tied up and off the road.

“That honestly takes time,” Arnott said. “If that is kind of what you’re proposing to take over, I mean, we’re fully supportive of that, that’s really where we need the assistance with mental health.”

Brown said the mobile unit would have at least two people, a driver and a licensed mental health professional who is capable of signing the affidavit that allows a person to be detained for 96 hours under Missouri law.

“I’m fully supportive of that, that would be a great program. That would be something that would benefit us in law enforcement,” Arnott said.

Sustainable funding for the future

Burrell is the technical assistant and the main consultant to the Missouri General Assembly on writing a funding model for mental health crisis centers across the entire state of Missouri. The state government places expenses from facilities like Burrell into the cost report for community behavioral health centers.

“What that means is we no longer have to worry about trying to find ways in which to bill for our services directly when an individual comes through our door. Rather, the expenses are accounted for on the back end,” Brown said.

The idea is to make crisis centers financially feasible for the long term, without regard for whether or not a patient’s health care insurance will cover their costs when they seek help for a mental health crisis.

Burrell uses a funding model found within the framework of the Missouri Department of Mental Health standards for Certified Community Behavioral Health Organizations (CCBHO). The state rules specify that a CCBHO must publish a sliding-scale fee schedule that is readily accessible to all clients. Every three years, the Missouri Department of Mental Health examines expenses at the Burrell Behavioral Crisis Center, and the track record of spending helps determine future funding allocations and recommendations from the state.

“It doesn’t give us a direct number of ‘You will be allotted this amount of money,’” Brown said. “About 80 percent of the expenses are covered, but it’s all in the backend.”

Gov. Mike Parson's plan for state use of American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding for 2022 included $1.1 million for “creating a registry for law enforcement, hospitals, state departments, families, and other partners to identify emergency and referral resources available for mental health and substance use treatments.” It also included $139.5 million for physical infrastructure projects for federally-qualified behavioral health organizations “to expand services for underserved populations, support COVID-19 accommodations, and expand programs to meet increased demand for behavioral health and substance use disorder services.”

In 2020, there were 1,125 deaths by suicide in Missouri. Suicides peaked in Missouri in 2018, when the Missouri Department of Mental Health documented 1,230 deaths.

Burrell is also working to establish a physical location for a youth mental health crisis center in Springfield.

“This really will be life-changing for numerous individuals across our county,” Brown said.

Suicide prevention resources

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 1-800-273-TALK https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org

Ask, Listen, Refer https://moasklistenrefer.org

Crisis Text Line: Text MOSAFE to 741741 to text with a crisis counselor, or visit https://crisistextline.org

Veterans Crisis Line: 1-800-273-8255

LGBTQ crisis hotline, the Trevor Project: 1-866-488-7386