IN-DEPTH

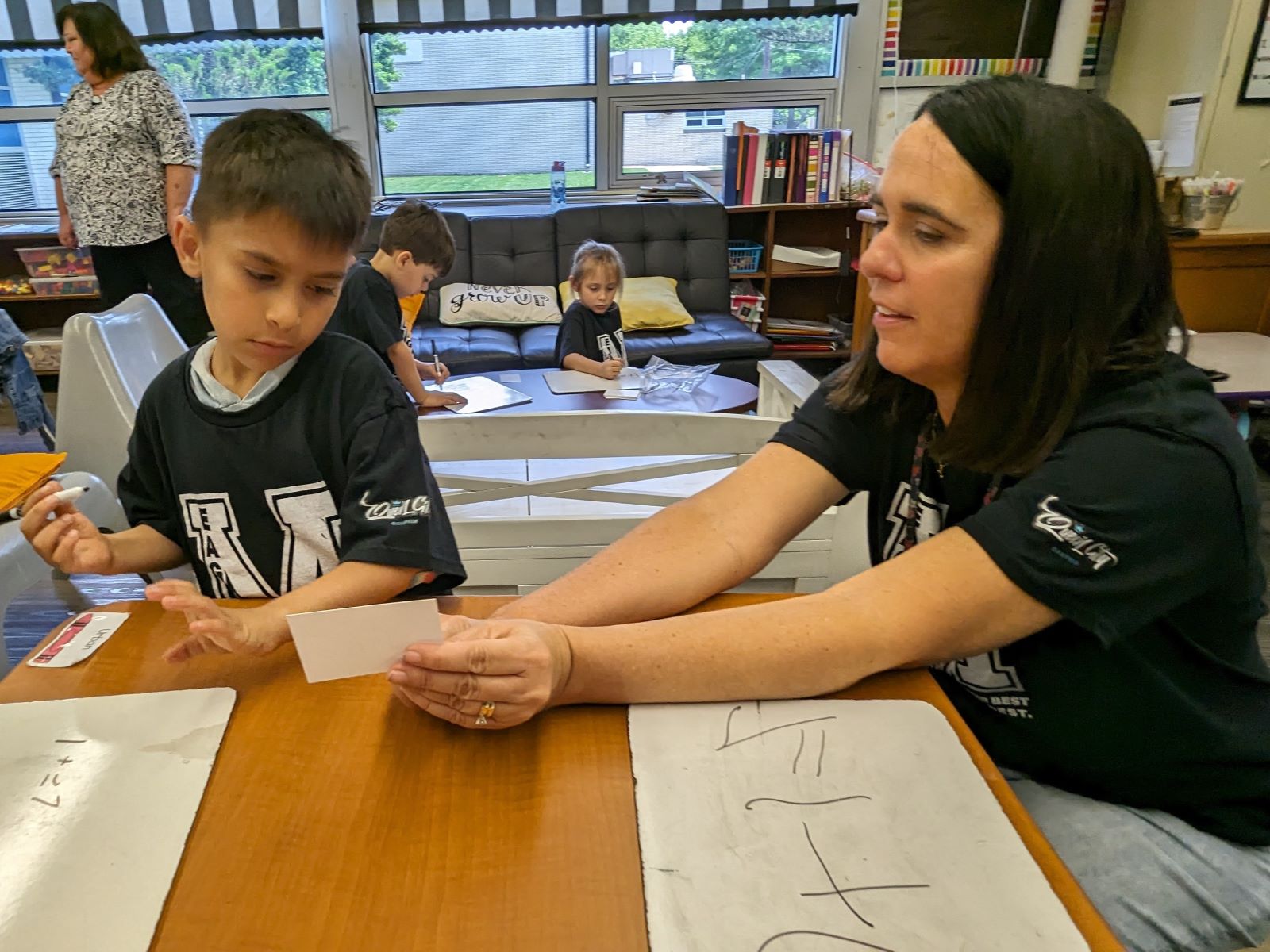

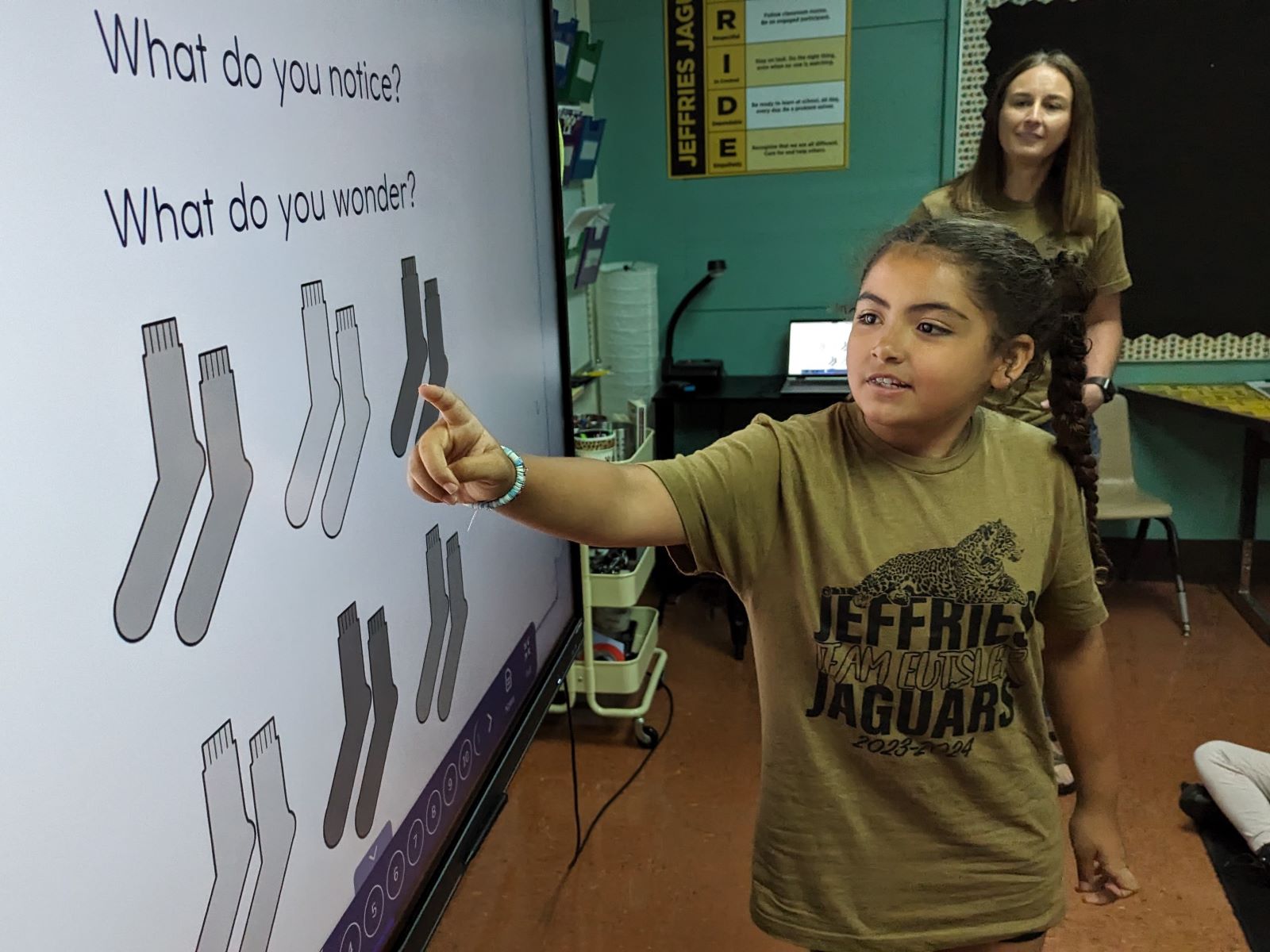

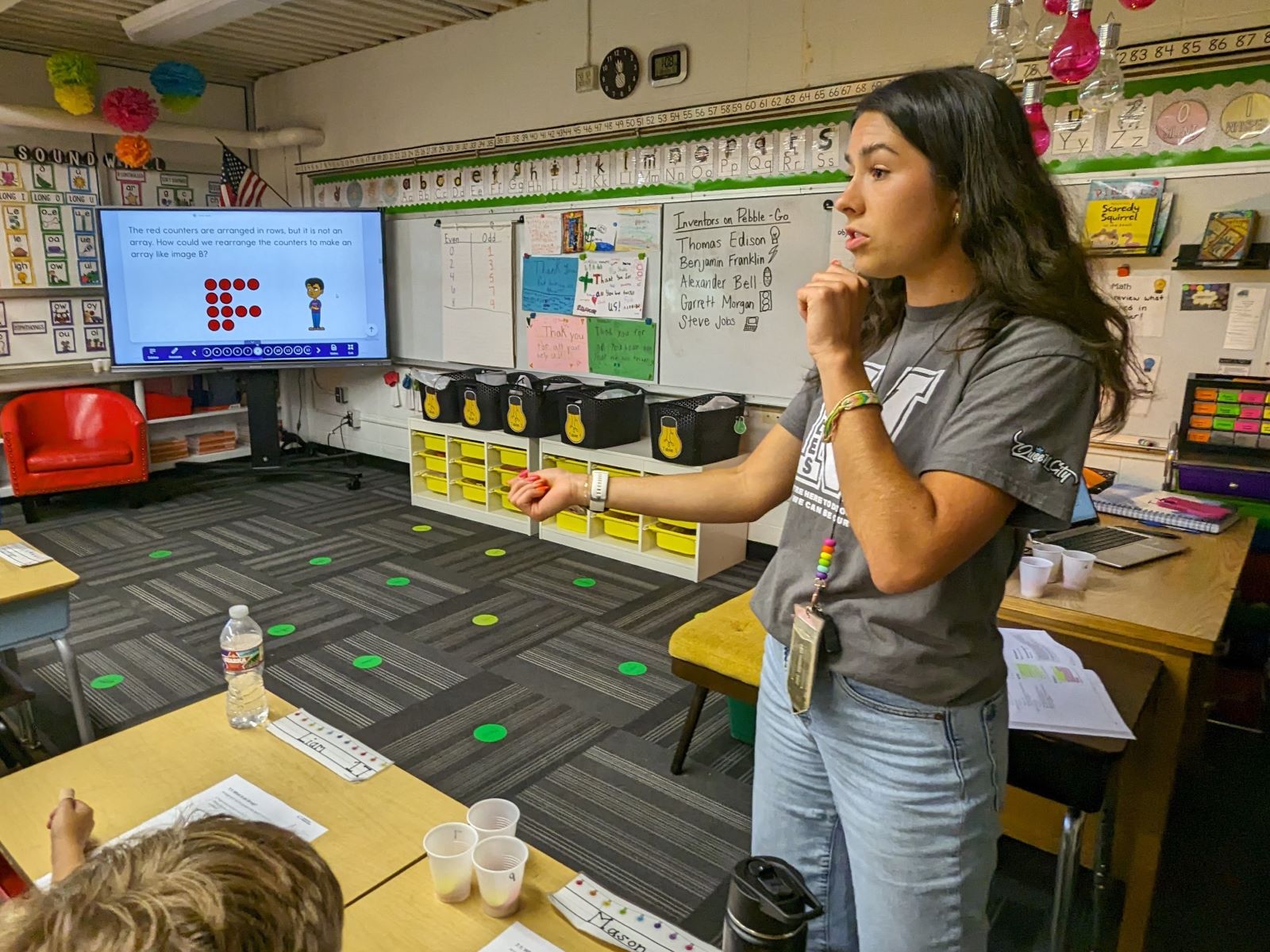

Tabitha Eutsler watched her third-grade students at Jeffries Elementary tackle a problem about area and perimeter, and saw that every student was approaching the problem differently.

Some students drew precise rectangles and squares on graph paper. Some students opted for regular paper. Some students used their fingers, while others used their heads.

As she watched them all bring their own methods to the problem, she noted that this didn’t resemble what she saw in math classes of the past.

When Eutsler started teaching 14 years ago at Jeffries, she taught one process for tackling this task. And when she was a student at Jeffries, she remembers her teacher explaining the same process.

Over the last about five years, however, Eutsler and other teachers across Springfield Public Schools have been using a newer curriculum. Known as Illustrative Mathematics, it approaches the education of math a bit differently.

Eutsler said the curriculum allows students to get a deeper understanding of mathematical concepts through exploration and teacher guidance. Rather than memorizing formulas and learning one way to work problems, students are getting into the mechanics of math.

“I love to see the different ways that their brains work,” Eutsler said, talking about all the different ways her students tackled the area and perimeter problems. “There were all these different ways, but we are all ending up at the exact same answer. And that’s because the curriculum is set up to do the problem in the way that makes the most sense to you. We’re not locking kids into only one way to solve problems.”

Newer math curriculum settling in

The change is part of a new math curriculum students in Springfield have been using for the last few years.

SPS is using a version of Illustrative Mathematics adapted by Desmos Classroom, a subdivision of the curriculum company Amplify. Illustrative Mathematics, now offered by Kendall Hunt Publishing Company, was initially developed by Bill McCallum, a distinguished professor of math at the University of Arizona. He got to work in 2011 as part of that university’s Institute for Mathematics and Education.

McCallum said that after he and others helped develop the Common Core national standards, people wanted illustrations of those standards, and lists of simple tasks that would help students understand the concepts and skills to meet those standards.

Over the last year, portions of the system have been adopted in bigger cities, such as Philadelphia, Denver and New York City in an attempt to bolster stagnant test scores in math.

Springfield has been using it for almost seven years. Starting with the middle school grades 6 to 8, the school district expanded Illustrative Math to some pilot programs in lower elementary grades, as well as high-school level courses, said Whitney Evans, a secondary numeracy coordinator with SPS.

The COVID-19 pandemic set back progress in building math proficiency, Evans said. But when a committee of SPS teachers and administrators met to evaluate their programs, the Illustrative Mathematics program drew favorable reactions. The Springfield Board of Education recently approved its continued use for grades 6 to 8, based on the committee's recommendations. An evaluation of the curriculum for grades K-5 is ongoing.

“Every single member of the program evaluation committee for 6 to 8 voted to keep and revise our current Illustrative Mathematics curriculum,” Evans said. “We have a lot of buy-in at the middle school level. At high school it was a little bit more split, but because we have good data coming out of middle school, and because we had such a rocky start with COVID, it was just a tough time trying new curriculum.”

New methods for getting correct answers

Just like in other forms of math, 2 plus 2 equals 4 in Illustrative Mathematics.

What makes it different is the angle of approach, said Patrick Sullivan, an associate professor of mathematics at Missouri State University. Instead of trying to make all of its connections in a mathematical basis, Illustrative Mathematics introduces math through conversational language and real-world examples.

“As you look at problems, you’re going to see where the goal of this curriculum is what we call low floor, high ceiling,” Sullivan said. “Meaning that we can get more students into the problem, but then we have the opportunity to take it as far as we want to go with it, and not lose students early on.”

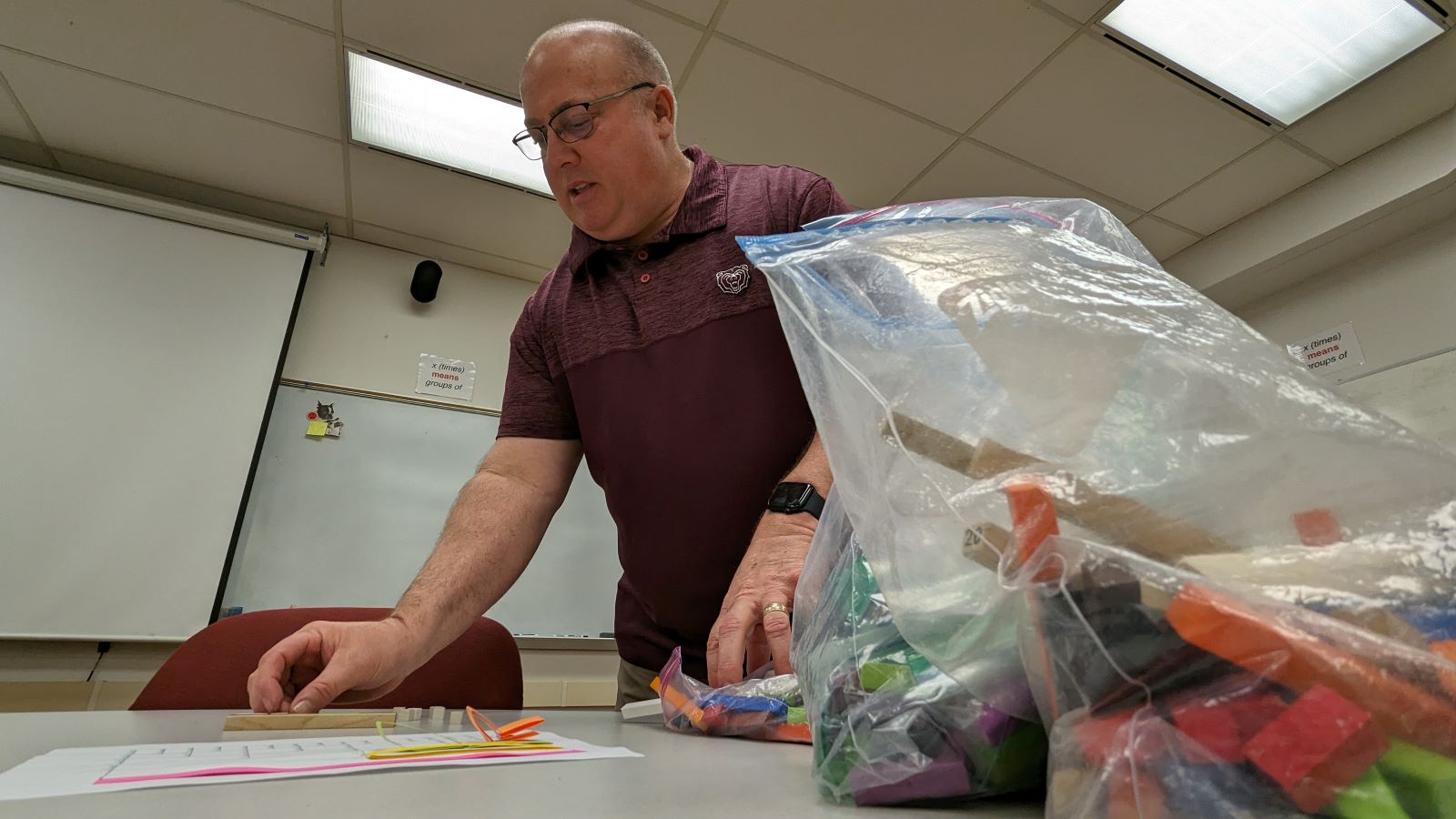

In addition to his work at MSU, Sullivan is also the author of “See It, Say It, Symbolize It: Teaching the Big Ideas in Elementary Mathematics.” In that book, he uses his familiarity with Illustrative Mathematics and other newer math education ideas to reinforce connecting mathematical concepts to plain language.

Fractions are a prime example: They are one of the more difficult concepts in math — Sullivan said in the world of elementary math education, “fractions” are the F-word. Most traditional math programs have started from the beginning by starting with mathematic expressions, definitions of numerators and denominators, etc.

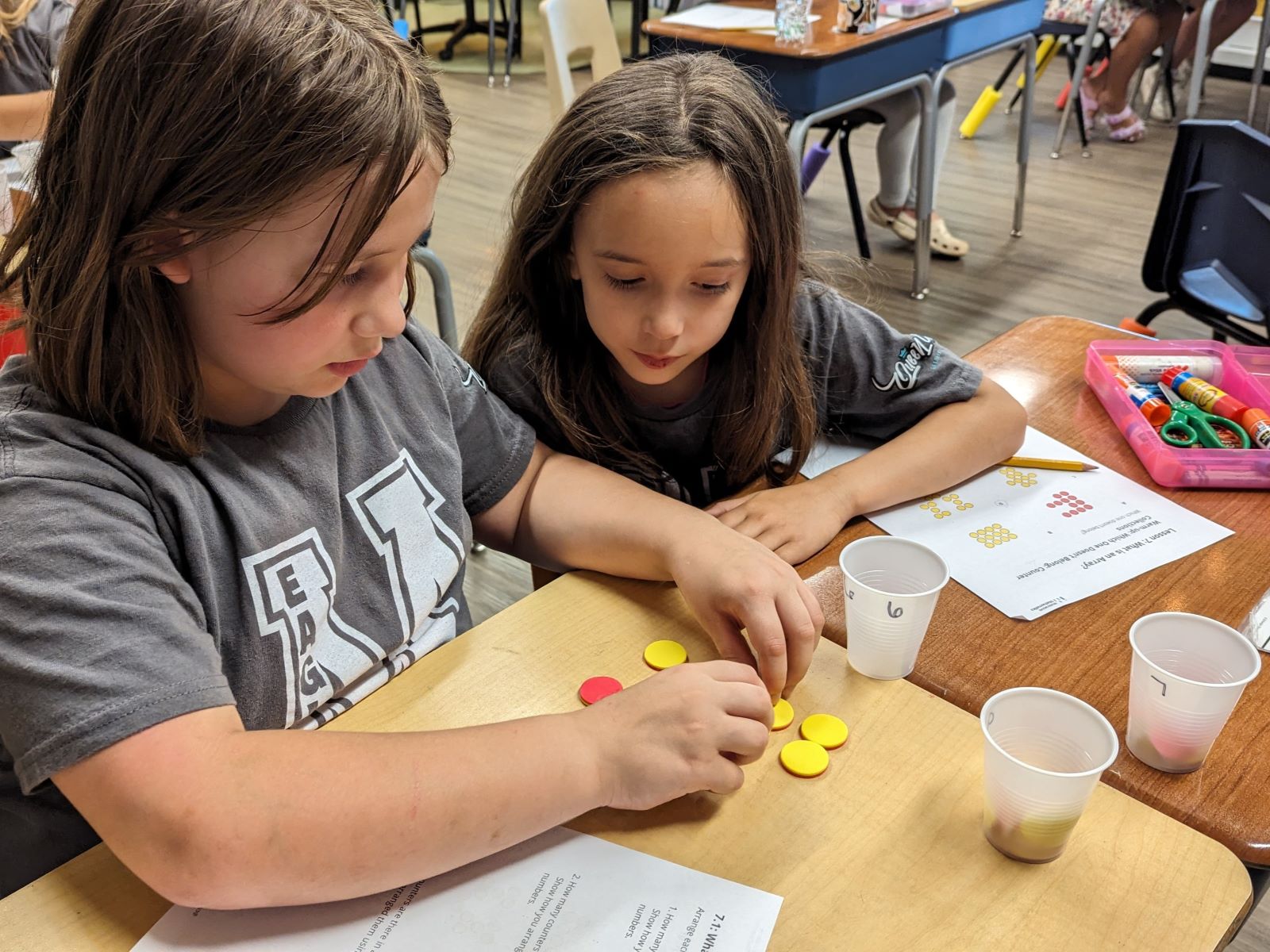

Illustrative Mathematics is different, Sullivan said. Digging through a few educational supply closets at Missouri State University's Cheek Hall, he pulled out a set of brightly colored sticks — Cuisenaire rods, they are called. They are small, boldly colored sticks. Sticks of certain lengths have the same colors.

As Sullivan scattered dozens of rods across a table, he found rods as short as a centimeter and as long as 12 centimeters. He demonstrated how, as students play with them, they can see how six of the 2-centimeter rods exactly match a 12-centimeter rod. Or two of the 6-centimeter rods. Or four of the 3-centimeter rods.

Sullivan said that means before learning mathematical notation, students are learning the definition of the words “thirds,” “fourths” and more.

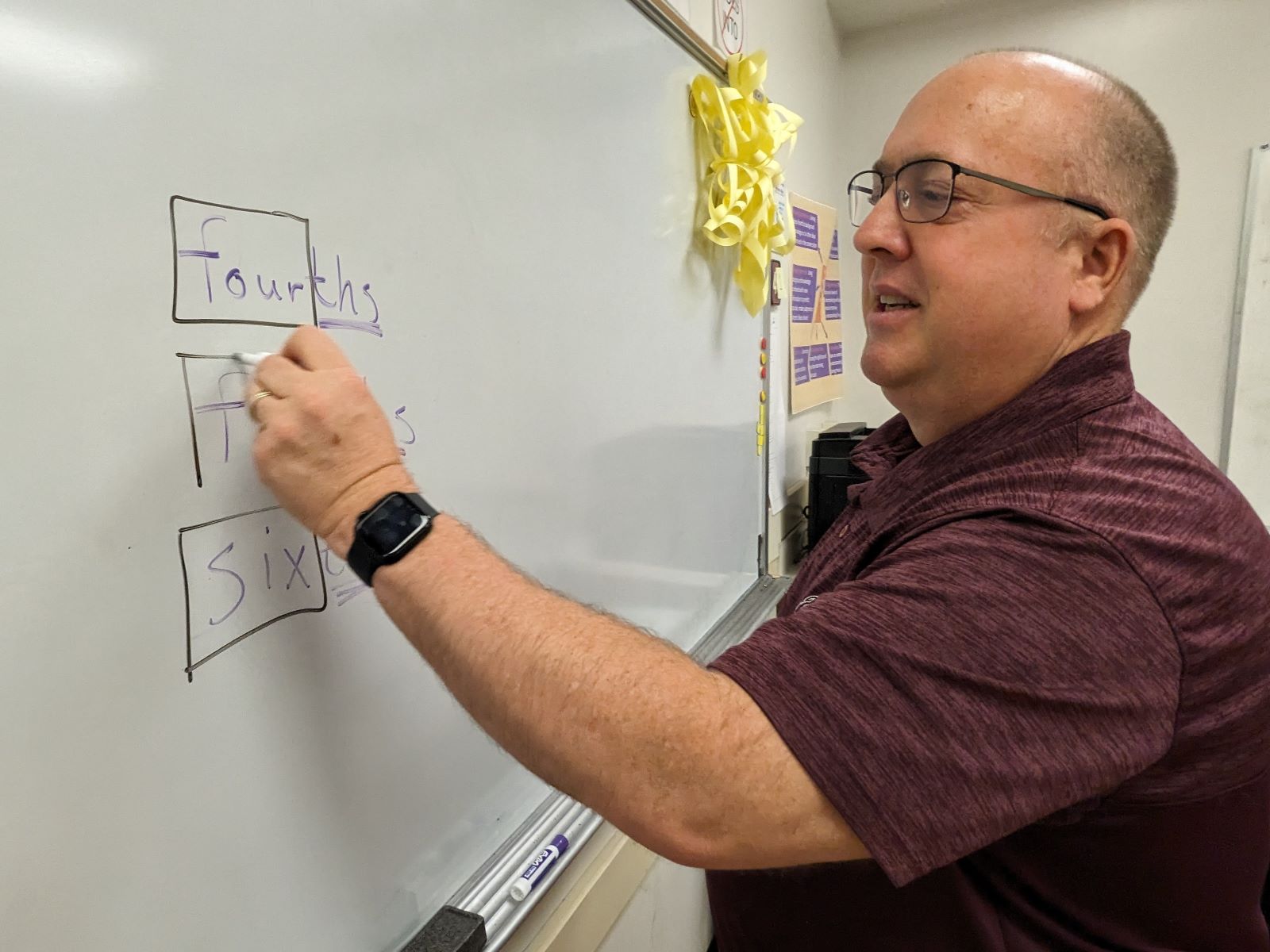

Moving to a white board, Sullivan wrote some fractions. Beside those numerals, he wrote “fourths,” “fifths” and “sixths,” then highlighted how those words had the written numbers for four, five and six.

“That’s a strong language acquisition principle,” Sullivan said. “They are saving that math notation for later.”

Illustrative Mathematics lessons include many similar introductory concepts for lessons. In exploration sessions, students are encouraged to make observations about how things are the same or different. In these explorations, there are no correct or incorrect answers — odd with the world of math, but even with how kids read.

Eutsler said it’s a welcome revolution. She said that society encourages all children to be readers, but we can just as easily encourage kids to be mathematicians.

“We have focused on reading for decades, but reading and math go right together,” Eutsler said. “Now we are making that same deep connection to math, and I’m excited to see where it’s going to lead us.”

The switch to Illustrative Math was a calculated move

This is no light, flippant decision.

Missouri’s largest public school district is just as beholden to Missouri’s academic performance standards, and a major part of earning accreditation from the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education relies on standardized test performance. If SPS students continually fail to show improvement, the school district risks losing local control over some of its operations.

“We want to follow the guidance we get from DESE, so any decision we make is going to be aligned to Missouri’s learning standards,” Evans said. “DESE has also provided us with guidance on math practices that we want to instill in all of our students.”

But state accreditation is not the only bar to clear. Springfield has a growing number of private school and homeschooling options, and the surrounding suburban school districts offer higher academic performance for families who can afford to move to them.

After the school district’s evaluation and recommendation, a discussion about the curriculum took almost an hour of deliberation during a Springfield Board of Education meeting in December. Board member Maryam Mohammadkhani asked for an expenditure for K-5 Illustrative Math curriculum to be pulled out of a consent agenda and discussed separately, voicing concerns that Illustrative Mathematics might not be the best choice for students.

But after having concerns and misconceptions about workbooks addressed, and hearing confidence from members of the evaluation committee, the school board voted 6-0 supporting Illustrative Math (Board member Steve Makoski was not present for that meeting).

Later that night in December 2023, board members were shown how math scores improved in the latest round of Missouri Assessment Program testing:

- Performance for math in sixth and eighth grades finished above the state average.

- Students showed significant increases in proficiency for sixth-grade math and end-of-course Algebra 2.

- Students across the board improved math scores almost 2% over last year. This reduces a gap between Springfield and the state to less than 2%.

At another board meeting in February 2024, Deputy Superintendent of Academics Nicole Holt reported that Galileo screenings showed encouraging results. Galileo is the program SPS uses to prepare students for MAP tests.

“That shows how hard our teachers have been working and leaning into that curriculum, to help our students attain that growth,” said Callie Baldwin, elementary numeracy coordinator for SPS. “What we’ve done with our committee said IM is really rooted in research from the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, as well as just best practice.”

Generational change causes frustration for parents

The difference in instruction has equaled frustration for parents who learned math by traditional methods and who are struggling to help their children with homework.

In the case of multiplying two three-digit numbers, for instance, a technique called box multiplication differs from a traditional algorithm. The traditional method breaks the problem into smaller products and adds them together, and so does box multiplication. But in the box, a student starts from the hundreds spot, while the traditional algorithm learned by many parents starts at the ones.

And because the method behind Illustrative Mathematics is language based, that means there are more word problems, and fewer simple exercises. According to a parent who wrote an email to the Springfield Board of Education, that means homework does not offer the repetition of traditional math assignments.

Being uncomfortable and anxious is part of learning. It means we don’t know something, and we’re trying to figure something out. That’s a natural part of learning.”

Patrick Sullivan, associate professor of mathematics at Missouri State University

Sullivan said that even the concept of practice has changed dramatically. Math education for older generations involved plowing through a slog of math problems structured to aid memorization of a process.

That means student assignments of 2024 look drastically different than they did 20 or 30 years ago. Instead of a grid of problems, students have to puzzle out word problems or other exercises.

Sullivan said parental frustration is bound to occur, because Illustrative Mathematics is a thorough change. It’s no surprise that parents — especially those who are invested and involved with their children’s academic success — would express frustration with not being able to help their kids.

Don’t worry, he counsels. Older generations learned a procedural understanding, but Illustrative Mathematics teaches a conceptual understanding.

“Understanding conceptually is messy, and takes more time,” Sullivan said. “But it’s more sustainable. It develops a deeper understanding.

“I would tell parents to just be patient, and be supportive of the struggle and challenges. I cannot stress this enough. I deal with this on the collegiate level all the time. Being uncomfortable and anxious is part of learning. It means we don’t know something, and we’re trying to figure something out. That’s a natural part of learning.”

Springfield Public Schools offers supplemental lessons and family supports for math, as well. The assignments allow parents and students to work together if a student is in need of more help. Videos and other materials are also available from the SPS Canvas page. And parents of K-5 students were sent home with summer practice workbooks.

“We have unit videos that are built for parents as the audience,” Baldwin said. “They are intentionally created for parents to help bridge the gap, so they can help their students at home.”

Ready to solve some problems?

Curriculum offers teacher supports

Sullivan said parents aren’t the only ones dealing with a thorough change.

“You have every entity in the school district involved with math having to shift how they think about mathematics,” Sullivan said. “Students have to think differently. Parents have to think differently. And teachers are having to think differently, quite frankly.”

Students can get emotional about math, Eutsler said. She knows this because she said that she still gets emotional when she struggles to understand something.

“There is much more emotion, because lots of times it comes from how someone thinks they are either a math person or they are not,” Eutsler said. “That gets me going right there, because we call every kid a reader. Well, every kid can do math. Every person is a math person, and we’re changing the mindset around what math is.”

Illustrative Mathematics is also designed to support teachers with clearer instructions and sharper focus. A lesson starts with a warm-up, then moves to activities that teach the main points. There is a synthesis period where students put things together, then a cool-down, where students and teachers “wrap it up and put a bow on it,” Evans said.

Evans said the curriculum dives even deeper with a rich offering of teacher supports, from discussion questions to anticipated misconceptions, and even important discussion points to cover in a classroom conversation at the end of a lesson.

If SPS is going to ask teachers to do more than they ever have before, Evans said it was important to give teachers high-quality tools, and Illustrative Mathematics meets that standard, she said.

“There is still an expected endpoint that we need our students to reach, and we are not just going to cross our fingers that we give them a task and they get it,” Evans said. “Our teachers are highly skillful at facilitating discussions to wrap up each lesson, so that the students are learning what they need to.”

Springfield is a big district, with classes that vary greatly from Eutsler’s. The school district’s own data shows that some schools have not made as much progress as others getting into the new math curriculum.

But Eutsler said she is seeing changes in her students, year to year, and she also sees a change in herself. At the end of her first, difficult year with the curriculum, she watched as students who usually struggled with math bring her their own ways to do problems and get the correct answer.

With every year that passes, she sees her students become more confident. When struggles happen, she sees more confidence, grit and perseverance.

“I think it comes back to what’s best for kids,” Eutsler said. “We can have kids who regurgitate math acts and solve an algorithm. Or ultimately we can have kids with confidence, critical thinking and reasoning skills, being able to defend their answer and have deep conversations with someone next to them. How much more powerful is that? In my experience so far, this is the curriculum that does that.”

Reporter's note: This report has been edited to correct the grade of a teacher and her students.