IN-DEPTH

In January, officials with Springfield Public Schools and the City of Springfield shared excitement about possibilities for building a new Pipkin Middle School at Nichols Park.

Only two months later, that idea fell apart.

Almost miraculously, another piece of land emerged as a possibility, so that the school district could make a construction proposal to voters in April.

But concerns over nearby railroad tracks limiting access and conflicting zoning led the Springfield Planning and Zoning Commission to reject the idea. The school district eventually backed out of the deal.

The planning and effort done over the past year, in searching for a place for Pipkin, was detailed in email records obtained by the Hauxeda as part of a Missouri Sunshine Law request.

Emails, documents and communications about Pipkin Middle School between officials of the school district, city of Springfield and Springfield-Greene County Park Board, written between Jan. 1 and Sept. 18, were requested.

The emails indicate a roller coaster of excitement and disappointment, as officials celebrated possibilities and dealt with frustrations over those possibilities evaporating.

The emails also show exactly how challenging the job of finding a suitable building site remains.

A place for Pipkin: Email records show how tough that is to find

The results of our Sunshine Law request reveal significant efforts to find an affordable, optimal location for Pipkin Middle School.

Pipkin in need of a new building

Of the district’s nine middle schools, Pipkin Middle School’s student population is the most diverse. About 78% of its population qualify for free and reduced-price meals. It houses about 580 students in sixth through eighth grade, as well as more than 60 staff members.

It is an International Baccalaureate Middle Years World School, part of a program that offers challenging courses that connect students to real-world issues. It also has been named an at-risk school, and is part of a partnership with Yale University and Drury University known as the Comer Project, a system that helps increase parent involvement and boost teacher development.

Pipkin Middle School is housed in a more than 100-year-old building at 1215 N. Boonville Ave.

It is not ADA-accessible, and features a labyrinthine construction that does not lend itself to allowing students to make smooth transitions between classes. Its footprint is contained in a 3.07-acre site that is surrounded by other developments.

The basement classrooms flood sometimes, and the smells from previous floods hang in the air. The school has only two sets of restrooms among its four floors, requiring the use of bathroom-specific breaks. According to a district measurement of its buildings, Pipkin is in the worst condition.

It stands in stark contrast to the new Jarrett Middle School, located at 906 W. Portland St.

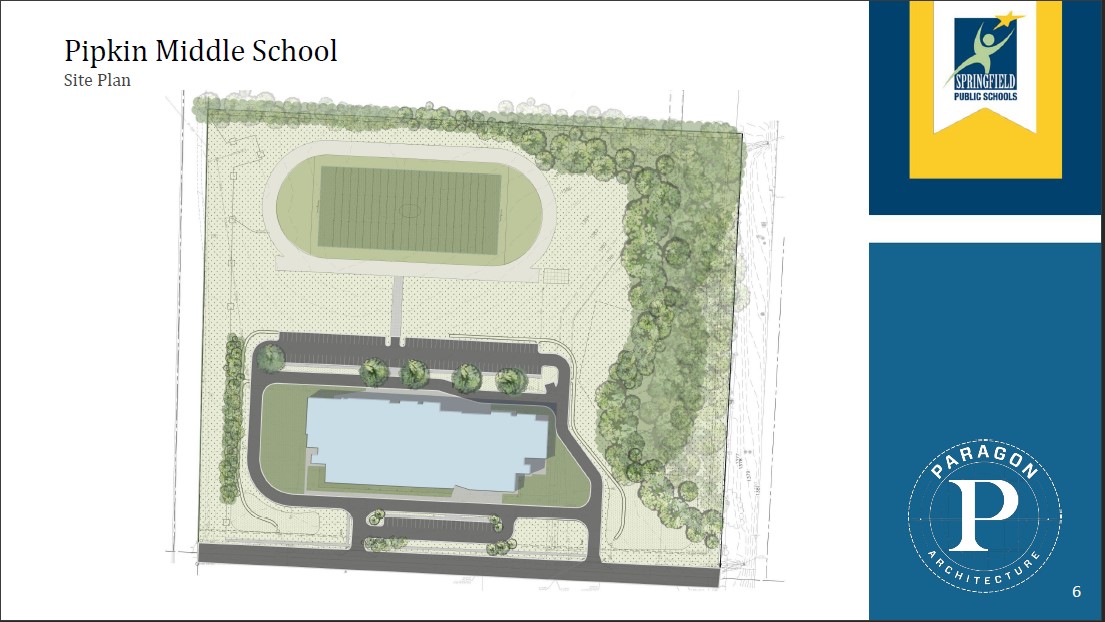

In April, Jarrett students moved from a building on Jefferson Avenue that is almost as old as Pipkin. The $41 million project includes a state-of-the-art school building with more than 130,000 square feet, as well as an athletic center and stadium for football, track and more. It sits on a 9.5 acre property that used to house Portland Elementary.

Voters approved construction of the middle school in 2019, in a ballot measure called Proposition S. The district used the same name in 2023 for a new package of construction, and one of those construction projects aimed to give Pipkin the Jarrett treatment. That election, held on April 4, passed with a strong 77 percent approval rate.

The $220 million in construction projects were given an estimated completion of 2026. While every other project in 2023’s Proposition S had a well-established address, the Pipkin project’s location was announced to voters days before the election.

Email records show that late announcement of land was not part of the plan.

Nichols Park offered ‘unique school-park scenario'

Finding about 10 acres of land in the Pipkin sending zone is challenging. The zone stretches east to west, starting less than a mile west of Kansas Expressway and ending at U.S. Highway 65. It is about five times as wide as its height, contained roughly by a rail line north of Commercial Street to the north, and the east-west Chestnut Expressway and Pythian Street to the south.

But a clear candidate emerged: Nichols Park. Situated on the western side of the zone, the 16.2-acre park offered plenty of open space in a residential neighborhood.

According to an email between Bob Belote, Springfield-Greene County Director of Parks and Recreation, and John Mulford, then Deputy Superintendent of Operations for SPS, the Park Board was excited about the school district’s pitch to build there collaboratively.

In an email dated Jan. 5, Mulford wrote about a joint project where the school district would build the Pipkin it wanted, then make other nearby land available to the public as parklands.

The city and school district would share maintenance costs while the school district would foot the bill for all the construction and nearby improvements, according to the email. Certain areas of the park would be open without limitations, while other areas would have limited access during school hours.

Belote wrote that the Park Board was excited to partner with SPS about “this very unique school-park scenario.”

“Very exciting stuff here, John,” Belote wrote in an email dated on Jan. 5. “We look forward to where this important discussion will take us!”

The two discussed organizing a site visit to identify other areas of concern. Time was of the essence: According to the email, the school district wanted to have a public announcement by Feb. 1 so that it could begin informing neighbors, and so a community group in support of the issue could start campaigning.

Complications arise with Nichols

As the site was studied, it emerged that the Springfield-Greene County Park Board received money for Nichols Park from the federal Land and Water Conservation Fund. According to an email from Mulford, district officials told board members on Feb. 28 in a closed meeting that Nichols Park was off the table, because of construction restrictions imposed by the terms of federal grants.

On March 3, Jenny Fillmer Edwards, public information officer for the Park Board, sent an email to KSMU radio reporter and editor Gregory Holman detailing some of the findings. That email was CC’d to Stephen Hall, chief communications officer for SPS.

Edwards wrote that the grants are intended to give long-lasting protection to park sites, which are supposed to be used for outdoor public recreation. Properties that receive grants are subject to some stringent limitations.

“Federal regulations dictate what can and can’t be done with sites once they receive these grants,” Edwards wrote. “If any redevelopment or change in use is proposed for a LWCF site, the Park Board must study the regulations and figure out if the proposal fits.”

Such studies have been done in the past, Edwards wrote: “Our staff does this often, because LWCF includes so many sites.” Park boards can request conversions of properties in some cases by asking for a review from federal grant administrators.

But such a process might take two or three years to study, and the answer at the end of that time might be a denial, Edwards wrote.

Searching for a Plan B

Based on the records received by the Daily Citizen, Springfield Public Schools scrambled for another building site.

SPS Deputy Superintendent of Operations Travis Shaw was working as the school district’s executive director of operations in March. In July, he replaced Mulford, who in December was hired as superintendent of Fayetteville (Arkansas) Public Schools.

In September of last year, Tim Rosenbury, director of Quality of Place Initiatives for the City of Springfield, wrote to Shaw about a place with promise: Some holdings of the Assemblies of God headquarters at Boonville Avenue and Division Street, just two blocks north of the existing Pipkin.

Rosenbury is an architect and a former president of the Springfield school board. He played a key role in the development and passage of the 2019 school district bond issue.

In an email dated Sept. 14, 2002, Rosenbury wrote that city officials had discussed the status of several properties of which the Assemblies of God was studying for long-term use, and whether they could be considered surplus:

- The former Campbell United Methodist Church at Division and Campbell.

- Two apartment buildings facing Campbell and Hovey streets.

- A Health Care Ministries building at 521 E. Lynn.

- A four-story warehouse at 1429 N. Campbell Ave.

Rosenbury in that email pitched the possibility of stripping the warehouse to the frame on the existing foundation, and demolishing the other buildings.

“As I think about alternative sites for Pipkin Middle School, the acreage and the four-story warehouse intrigue me,” Rosenbury wrote. “The site is easily big enough to accommodate the same program elements that the new Jarrett will have, and the warehouse is a simple concrete structure that is the same depth (and similar column spacings) as the classrooms wings as the new Jarrett.”

Shaw in March contacted Rosenbury about that possibility, asking for a church contact he could share with Jeff Childs, a senior advisor with SVN/Rankin Company who works as a real estate agent for SPS, according to the email records.

Shaw wrote Rosenbury again a month later after the school district announced what turned out to be a controversial place for Pipkin.

Pythian chosen for cost-effectiveness, timeliness

Five days before the April 4 election, Springfield Public Schools announced it had entered into a contract with 4GS-Investments LLC to purchase 20.9 acres of land at 3207 E. Pythian St.

Mulford on March 21 wrote to board members and other officials that Childs had identified the property as a possibility. At the time, the land was not listed for sale — Childs was directed to reach out to the family that owned it. A price of $5,485,950 was agreed to — the amount was equatable to $261,360 per acre, or $6.025 per square foot, Mulford wrote.

In that email, Mulford wrote that the price was in the midpoint of comparable sales in that area, but was a lower-priced option compared to two other alternatives — and much more favorable.

Building at the district’s transportation center at 2945 E. Pythian St., next door to the Central High School baseball field, would require relocating the home of SPS’s school buses, Mulford wrote. Cost estimates for that relocation came in at $2.5 to $3 million, and a new center built on vacant land would cost about $10 million.

And building a new Pipkin at the school’s current site would be even more costly. Mulford wrote.

“To rebuild at the current site, the district would spend $3 million to $4 million between acquiring neighboring properties and demolition costs,” Mulford wrote. “And the building still wouldn’t be in a great location.”

Mulford estimated demolition costs at about $1.7 million and land acquisition costs for nine separate single-family homes and four separate commercial properties at $1.5 million to $2.25 million.

All that work would result in having only about seven acres — not the minimum nine acres needed for a Jarrett-like project. Construction would not be able to start until a renovation of Reed Academy was completed — projected to take about three years.

The construction cost savings paired with the ability to use eligible funds from the 2019 bond package and the prospect of selling land unused for a new Pipkin, encouraged Mulford and other district officials to recommend buying the Pythian property. The contract required the passage of Proposition S, and provided a 60-day inspection period.

Concerns over Pythian site result in its rejection

On Sept. 13, well after the 60-day review period, the district announced that it would no longer pursue the Pythian site for Pipkin. In early June, the Daily Citizen was the first to report city staff objections to the site.

Records obtained by the Daily Citizen corroborate the public conversation over the property’s selection, and eventual rejection. On July 13, the city’s planning and zoning commission voted against the purchase, saying the land’s use as a school didn’t match neighboring industrial properties, and offered limited access in the event of emergencies.

One of the main concerns dealt with a BNSF railroad on the property’s western border. Those tracks cross Pythian, which is currently the only street that offers access to the site where the school would have been built.

BNSF officials said in July to the city and school district that the plan did not appear to include crossing improvements or signal installation on a rail line that usually sees more than 30 trains daily. The railroad company also noted that the Pythian property did not connect to Division Street.

Shaw in July objected to how BNSF characterized how they were “surprised” by the property purchase, and detailed how school officials had been working behind the scenes to address concerns. In an email dated July 14, a day after the rejection, Shaw said that school officials two months prior had spoken with a team from the city that included its liaison to the railroad company.

In that meeting, they discussed a 2006 study about building a grade separation similar to one on Chestnut.

“Our current plan does not show a way to connect our property to Division because BNSF has yet to even receive grant funding to even engineer the project let alone construct it,” Shaw wrote in that email to board members and school administrators. “In the event they do receive funding to construct it, the city will be required to build a roadway from Division to Pythian because the railway intends to close Pythian as part of the project.”

Emails in August show that the school and railway were able to meet, but that school officials felt like they got conflicting information from BNSF and the city of Springfield about future construction plans.

As late as Aug. 4, Shaw was working to set up a joint meeting between city and BNSF officials. The request happened days after Shaw and other school officials discussed issues with the rail company.

“During our conversation, there were comments made by BNSF that were contradictory to the information and direction we have received from the City in our previous conversations,” Shaw wrote. “At their request, we’d like to schedule a follow-up meeting between the three entities to clear up some items and hopefully get everyone on the same page.”

The records obtained by the Daily Citizen do not indicate whether that joint meeting happened.

Board unity over Pipkin decisions

Included in the Daily Citizen’s record request were several letters from community members and business owners expressing concerns about the property. Board members Maryam Mohammadkhani and Judy Brunner wrote that they were also hearing concerns.

The emails corroborate agreement by board members over both the purchase, and the decision to back off. In September, Board President Danielle Kincaid said the votes for both of those actions were 7-0 in favor.

But the email records also indicate a third unanimous vote: In responding to a July 26 request from Mohammadkhani asking for a review of concerns, Superintendent Grenita Lathan noted that the board supported moving forward with the purchase after the city’s initial P&Z denial.

“The board voted unanimously two separate times,” Lathan wrote in an email dated July 27. “First to purchase the land and then to reaffirm their commitment for administration to move forward with the understanding that the board would be required to override the decision of the city.”

An email from Brunner dated Aug. 20 suggests that the board had soured on the property by that time. Brunner, who joined the board in April after initial decisions were made on the property, asked about how SPS would “tell the story of how and why options were considered and ultimately rejected — with the exception of the current proposal.”

The board voted on Sept. 12 in closed session to walk away from the site.

Search for a site continues

As August discussions about Pythian progressed, email records show Springfield Public Schools was preparing to look elsewhere. Lathan in an Aug. 4 email informed board members that school administrators planned to meet with Springfield city administrators, Mayor Ken McClure and Childs to seek other possible solutions.

The school district is also returning to the findings of the Community Task Force on Facilities, an ad hoc group of 36 community members, board members and school administrators formed in 2022.

But the rejection of the Pythian site pushes back its projected completion date beyond its projected completion in 2026.

Reporter's note, Oct. 9, 2023: This report has been edited to correct a detail about Nichols Park.