On Tuesday, a group of 35 Springfield residents gathered to begin identifying which Springfield Public School buildings are in most immediate need of renovation and repair. In the process, they will recommend to the school board whether or not a bond issue to finance the projects should be on the ballot next spring.

About half of the group had a head start, having been part of the process in 2018 that led to a vote on a $168 million bond, approved by voters in 2019. That group identified about half a billion dollars worth of projects across the district, but recommended that they be re-examined and put before voters over three phases as part of the overall district facility master plan.

The first phase, district staff and task force members say, is a success story. The $168 million funded an early childhood center next to Carver Middle School, new Delaware and Boyd Elementary schools, renovations at Sunshine and Williams Elementary and the construction of a new Jarrett Middle School. The bond also allotted nearly $8 million to install secured entrances at 31 schools.

Enough of those projects came in under budget that it freed up funds to address some, but not all, of the projects the 2018 task force had outlined for a second phase, including renovations to Hillcrest High School, a new York Elementary and two elementary storm shelter gymnasiums.

But as the latest iteration of the task force saw during their first meeting Tuesday evening, Missouri’s largest school district still has century-old buildings in need of at least attention, if not complete replacement. And construction costs have soared since 2018, meaning the $125 million in projects that the initial task force outlined for a second phase could now cost north of $200 million, according to district projections.

The conversations that task force members will have about how to move forward and which projects to prioritize will grow heated at times, said Cheryl Clay, who served with the first group and signed up for round two.

That’s why task force co-chair David Hall, safety director at Missouri State University and a retired Springfield Fire Department chief, encouraged the group to get to know each other during these first meetings before the work ramps up.

The task force is expected to present its recommendations to the SPS school board in October.

The process began the same way that the 2018 one did, with a tour of schools that scored failing grades on assessment from MGT of America Consulting, a firm the district paid to examine every building in the school district and score each based on its physical condition, its educational suitability and other variables.

“Then we get down to the fun part,” Clay said.

Process begins with tour of ‘the triplets'

Three middle schools — Reed, Pipkin and the former Jarrett — were constructed so similarly and so long ago that district staff refer to them as the triplets. None of them were built with any consideration for students or staff with disabilities. All of their basements tend to flood when heavy rains fall. Space constraints have plagued them all. But only one of them has so far been replaced.

The task force in 2018 selected Jarrett as a phase one project not because it received the consulting group’s worst grade among middle schools — that distinction went to Pipkin — but because the old Jarrett could be employed to house future middle schoolers in need of a temporary home if other district middle schools get replaced.

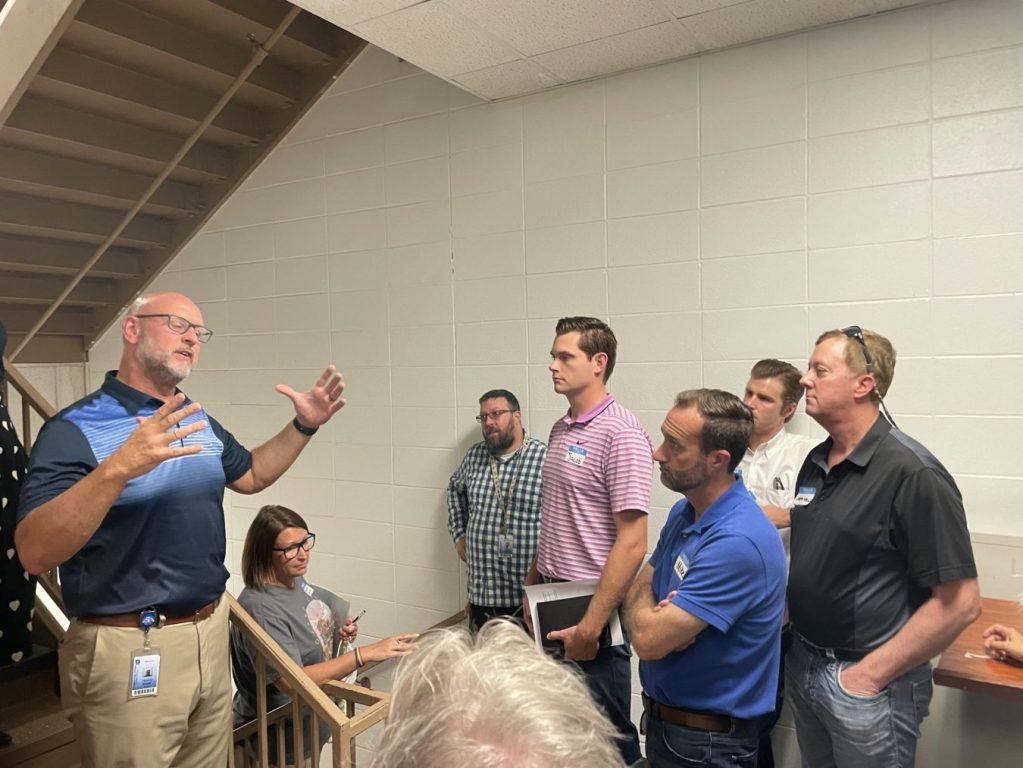

On Tuesday, the task force toured the two remaining triplets before putting on hard hats to view progress inside the massive $41.5-million Jarrett Middle School.

Before they got on the bus to visit schools, the task force members received no informational packets about the district’s facilities, or the grades that the consulting firm gave them. They didn’t even go around the room at the Community Foundation of the Ozarks and introduce themselves. They each got sheets to record notes for their visits, and encouragement to sit next to someone new each time you get back on the bus. That was all by design, said task force co-chair Bridget Dierks. The time to analyze the consulting firm’s grades and debate which schools to help and how will come during future meetings over the next several months. But first, the members need to view the situations and spend time together talking about what they noticed.

“I think it is easy to make assumptions about what the insides of school buildings look like without actually spending time within them,” Dierks said. “So it's really important to go and spend time in a building with someone who works in that building, and for them to tell you how the building functions for their students and their educators.”

STORY CONTINUES BELOW:

Pipkin: ‘Our kids really need more than what the school has'

John Cameron, a special education teacher at Pipkin Middle School, greeted members of the task force at the school’s entrance, which led them into a stairwell that renders the front door useless to students and staff with disabilities. It is one of several staircases that limits accessibility in the building.

“Whenever they take the elevator up, they're super slow,” he said. “This one over here, I timed it the other day. Took about three minutes to go all the way down just one story.”

Cameron pointed out water damage to the gymnasium ceiling, flood zones in the basement, the one staff bathroom in the school (“There’s always a line”) and tight spaces in classrooms built with smaller student bodies in mind than the 469 students the school now serves.

“I have put in a lot of hours in this school,” he said. “Me and the school principal have done a lot of things to improve it. We've actually powerwashed the front of the school here recently. We've painted different areas. Our kids really need more than what the school has.”

STORY CONTINUES BELOW:

Reed: ‘This is a classroom that used to be a restroom'

Due to space constraints, Reed Academy’s auditorium serves as a weight room and a four-lane archery practice area. What the auditorium does not provide is a stage.

“You’ve probably heard of our choir,” said Sara Strohm, Reed’s principal. “It’s amazing. It’s incredible. We can’t host a concert here because we don’t have room for them to perform.”

This year, Reed Academy is testing the possibility of becoming a fine and performing arts academy, which is an option that Superintendent Grenita Lathan has shown interest in bringing to the district. While Strohm was eager to sign Reed on, she said, “this is not going to work to have fine arts when our current choir, band and orchestra can't host their performances here.”

In schools like Reed, which recently passed its 100th birthday, efforts to update the building sometimes collide with pre-existing infrastructure. Strohm pointed out that the old bleachers, when fully expanded, extend well into the inbound areas of the Beavers’ basketball court.

The cafeteria, Strohm explained while in the gymnasium, only holds so many of the school’s 600 students who share lunch times, which is why the school’s custodian and an all-hands-on-deck team of school staff engage in a NASCAR pitstop-like conversion of the gym into a spillover dining space every school day. They have 15 minutes from the end of lunch to get it cleaned up and ready for PE students everyday, she said.

“This is a classroom that used to be a restroom,” Strohm said outside one room, which SPS board member Shurita Thomas-Tate asked her to repeat so all members of the task force heard it. Outside of Reed’s family and consumer sciences classroom, Strohm said it’s only big enough to hold 20 students, meaning that there are kids who want to take the class who can’t.

You make it work when you’re in there, said Rich Dameron, a task force member who taught at Reed for nearly a decade before joining the administration at Hillcrest High School, which underwent major renovations with funds from the first phase bond. But these middle schools were built for a different time, he said.

“I hope I get a new building,” Strohm said. “The kids deserve it.”

STORY CONTINUES BELOW:

New Jarrett: a glimpse of what could be

“Do you want to come this way, and we’ll go down and show you the stage,” bond project manager Barb Busiek said as she led part of the task force on a tour of what will be the new Jarrett Middle School. When the members turned a corner and first saw the stage, cafeteria space and a vast set of stairs that led down to it, several responded in awe.

“Wow,” said one.

“Ha!” exclaimed another.

Another ran up the stairs while comparing them to the ones from “Rocky.”

“It was intense,” said Trevor Holt, a task force member and rising senior at Parkview High School, after taking it in. “It was massive, open space. It was exciting, but also kind of crazy to see this, the absolute change and improvement.”

Holt went to the old Jarrett, and remembered the experience as a cramped one. On Tuesday, he took photos of the stage and cafeteria area from the base of what Busiek described as the learning stairs. It is a place that students can congregate during lunch breaks beneath a set of celestial windows that will fill the space with natural light, she said.

“We’ve seen Pipkin, we’ve seen Reed now, and now we’ve seen how Jarrett is going to function, and it’s really a lot different,” Dierks said.

Discussion begins

The task force will take one more facility tour next Tuesday, but the first talks began with a few observations and questions shared at the end of the first tour. While most remarked on specific deficiencies — lack of bathrooms, dysfunctional auditoriums — Mark Stratton flatly said that neither Reed nor Pipkin looked salvageable to him.

“If we’re going to be exemplary, hell, let’s be exemplary,” he said. “Jarrett is exemplary.”

STORY CONTINUES BELOW:

“I just have one question,” new task force member Tyler Creach said at the end of the night. “Talking with you guys on the last bond issue, it sounds like we're under budget on a lot of projects. We were able to do other things that maybe we weren't planning on. After seeing the condition of those two schools, why was that decision made instead of saying, ‘Let's keep this money to use to fix these two problems?’”

“Because the others were worse,” said Mike Brothers, a two-time task force member.

“I can answer that, because I work at one,” said Melanie Donnell, a kindergarten teacher at York Elementary, who added that her old school was “way worse than anything you’ve seen tonight.”

“I literally have no idea, so I'm asking,” Creach said.

Creach, who was the treasurer for the campaign of new school board member Kelly Byrne, was suggested for the task force by Byrne in board emails first obtained through a Springfield News-Leader Sunshine Law request. (The emails can be viewed here and here.) Byrne suggested three people for the task force — Tyler Creach, Bill Reed and Jeff Wells. Creach and Wells, a civil engineer, are among the new task force members.