The ruins of a tragic fire smoldered for more than 60 years before Tim Ritter came to piece its story back together — and, in the end, learn more about his own.

Ritter, a Fair Grove-based writer, recently published “Sarah Burning,” a fictional account based on a 1959 fire in Ava that resulted in three fatalities, great hardship and trauma carried through the family.

The event was deeply personal to Ritter, as members of his own family were killed in the blaze. Sarah, for whom the book is named, was his grandmother.

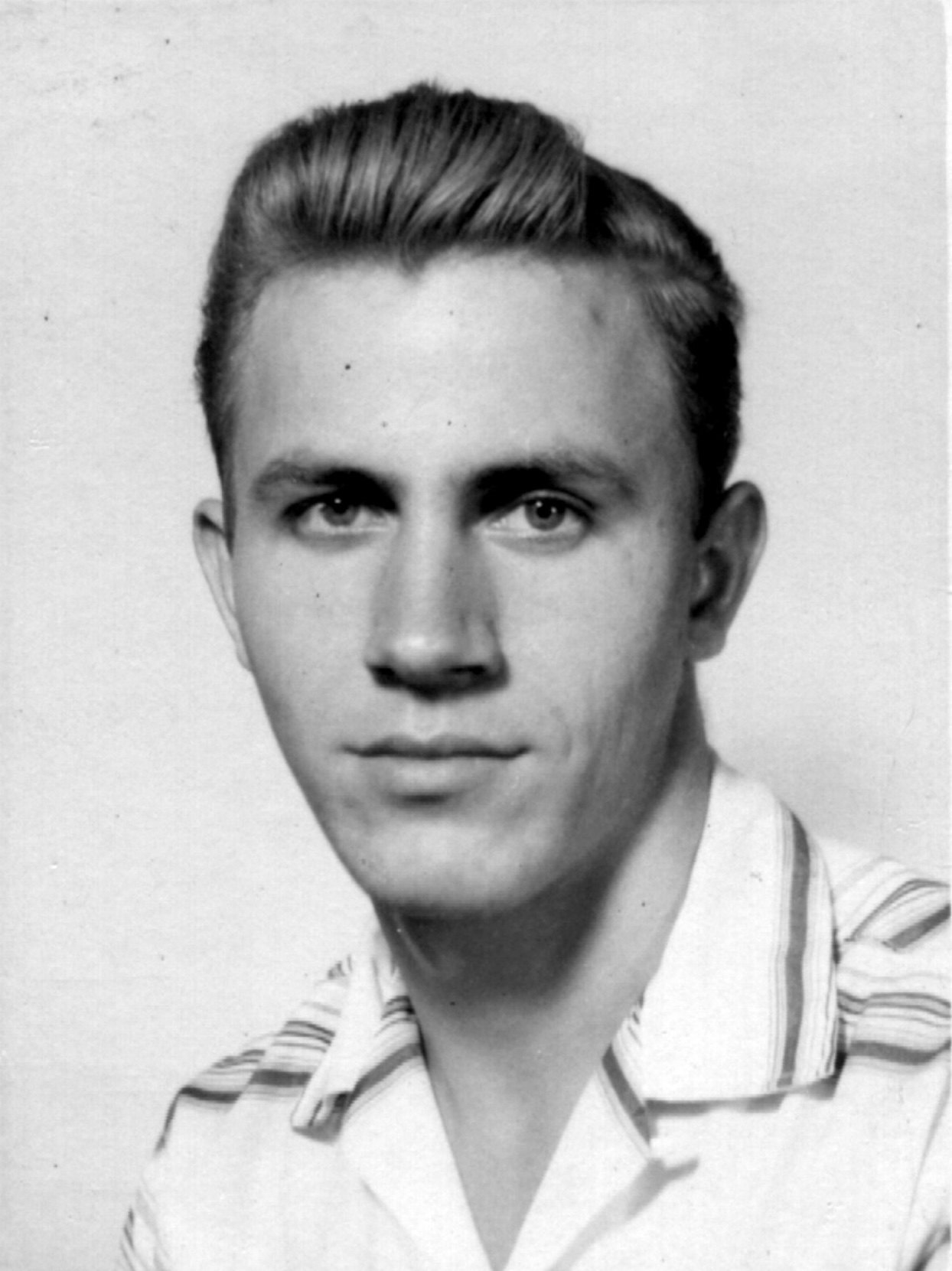

Her husband, Orville Ritter, was also in the house that night, as were two of their sons: Neil and Dewey, the latter there with his wife, Virginia, and 18-month-old son Gary.

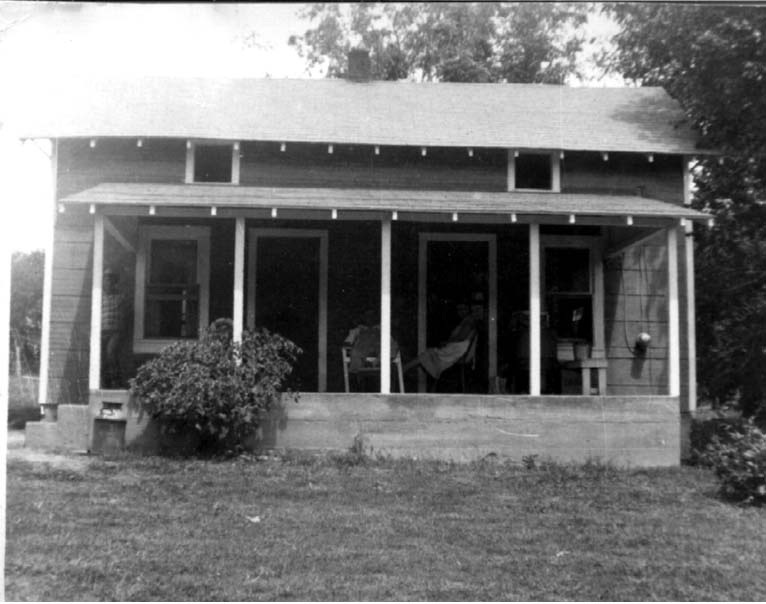

“A member of the family said the tragic fire possibly started from a heating stove on the first floor of the frame residence. All the family members were asleep on the second floor when flames fanned up a stairwell, cutting off escape.” – Springfield Daily News, Oct. 28, 1959

In the end, just three people survived: Virginia, Neil and Sarah.

“This is a story I have heard for almost my entire life,” says Ritter. “I knew about this fire, I knew that Granny was in the fire, I knew that Uncle Neil was in the fire; that there were these other things that went on. But it was all family legend.

“I told Mom one time, I said, ‘I want to talk to Uncle Neil sometime about the fire because I want to write about it someday.’ And she said, ‘Don’t you dare.’ She said, ‘Don’t you ever ask that man anything about the fire because he spent time in the psychiatric ward,’ which of course was a no-no, anybody having any kind of mental issue, shall we say, for lack of a more polite term. That was a no-no back then. You didn’t talk about it, you didn’t ask about it or anything like that.”

Not asking was difficult for Ritter, who knew from a young age that he loved to write. He speaks of a teacher in elementary school who introduced him to poetry; as a teenager, he also became fascinated with Edgar Allen Poe, whose impact is still seen in Ritter’s writings today.

“That just kind of opened up this whole thing for me, and I started writing,” he says of his early influence.

It was a dream mostly deferred, however, when he went to college to become an engineer.

“I eventually walked away from it (writing) because I thought if I was going to become a mechanical engineer I should be about logic, being serious,” he says. “But the whole time I was going to school up at Rolla, I’m writing and it became very personal.

“Rather than these creative, entertaining things, it became very personal. Going through relationships and all of that, I discovered that the imagery that you can create from whatever it is you’re feeling, whether it’s love, hate, happiness, sad, angry, whatever — all the imagery you create from that is just astounding.”

Which, at one point, led him to the conversation with his mom about the tragedy and the admonishment not to ask any questions.

Years passed, life happened, and a series of events led him back to the therapeutic reality of writing even while he still was working as an engineer.

“It was remarkable, the effect that it had on me just simply because I was able to do something that I loved, that I had for so many years ignored,” says Ritter. “That makes it so much better now that I’m at this point in my life where writing is my thing. I get to do that. I hate the word privilege because it has all kinds of other connotations nowadays, but it is the ability to go to my office and just do this. And just enjoy the heck out of it. It doesn’t have to be good. It doesn’t have to be perfect when you do that first brain dump. It just has to get out. And getting it out means so much.”

That chapter led to others, including his first book — “Soul Sketches” — marriage to his wife, Lisa — and a choice to step away from his engineering career to focus full-time on his writing efforts. It should also be noted that his interest in Ozarks history manifested in other ways, too, such as through deep interest in the Chadwick Line railroad, of which he is currently working on another book.

Such things eventually brought him back to the family tragedy. In recent years, though, time destroyed even more of the story about what happened that fateful night. One of the last links — the aforementioned Neil Ritter, who was the last living survivor of the blaze — died in 2011.

But for writer Ritter, it wasn’t the end — and six years ago, it became a beginning. That’s when he jumped in and began piecing together the events now told in “Sarah Burning.”

“I just started chipping away at it slowly,” he says. “Just spending a long time researching. I’d have to get away from it for a while because it was gut-wrenching. But when it finally came together I couldn't walk away from it. I couldn't unsee it.”

Time was spent pouring through newspapers, Ritter says, and looking for as many accounts and records of that time as he could find. He spoke with people who were in the area at the time, including friends of the family, to tell the story of those who can’t tell it now.

Ritter describes the book as a work of “creative nonfiction.” The conversations within its pages are fabricated — but Ritter notes that he feels they still align with the way things could have been.

“It helped that I knew these people,” he says of other characters in the book. “All of these aunts and uncles I refer to. All of those folks that played a role in all of this - I could hear their voices as I was writing this. I was thinking about how they talked and what I remembered about how they thought and all of that. I would throw it out to one of my cousins, ‘Does this make sense, does this sound right?’ I had a good sounding board for that, so that helped.”

Those conversations tie to larger themes and messages found through the book’s pages: Things, perhaps, that humans aren't meant to process.

“Here we have two very strong women who endured this entire thing and then somehow managed to keep going,” says Ritter. “Then also Neil who was dealing with PTSD before anybody knew what that was.”

“Dewey Ritter’s last words, heard while he was clutching his son and attempting to follow his wife out a second floor window, were ‘I’m burning up alive!’

“Dewey’s plea was heard by his 19-year-old brother, Dallas Neil Ritter, who already had leaped from the upstairs sleeping quarters.” – Douglas County Herald, Oct. 29, 1959

“Here you’ve got these three people who literally went through hell and somehow had to put a life back together. And so that became apparent, that there’s something bigger to this story than just telling this awful experience of the fire,” says Ritter.

“Dewey urged his wife to jump from the window but, she said, she must have hesitated because Dewey pushed her through the glass and she fell to the ground.” – Herald, Oct. 29, 1959

As a result of that final push, Virginia Ritter suffered a number of fractures and burns.

“To gain an appreciation for what that fall was like, I walked down into that area that she fell down into,” says Ritter. “I’m down there, and I’m looking up here like, ‘Wow, she came down that far.’ It was things like that that I’m just going, ‘Oh my God.’”

That land where he stood was also where Dewey and Gary died.

“You can be told things all day about a particular event. But when you’re standing right there where it happened, and you’re sizing it all up and figuring it all up, and it's like “Wow, that was a drop.’ It really gets to you.”

Orville Ritter, Dewey’s father, died a few days later due to the aftereffects of the fire. In addition to Neil, Virginia lived, as did Sarah — Ritter’s grandmother — but spent months in the hospital dealing with severe burns.

“Following the fire, Mrs. Ritter remained a patient at St. John’s for many months and was moved to the medical center in Columbia. … She re-entered the hospital in Columbia Sept. 9 and remained there until November.” – Herald, Dec. 8, 1960

All of the work, research and pieces came together for the book’s official release on Oct. 27, 2021, to coincide with the anniversary of the fire.

“The completion of it kind of means putting the legend to bed so we kind of look at reality,” says Ritter. “Here’s as close as we can come to what really happened. At the same time, It’s a wonderful celebration of those people. Especially in a way that was never done before because everybody kind of knew that Granny had some burns and all of that but nobody really understood. That family didn’t talk about a lot of stuff — you dropped it and went on. (This book is) putting it to bed but celebrating those people.”