“Legacy Ozarkers” is a place where we learn about — and from — residents with deep roots in the region. Individuals featured in this column are either 80 years old or greater, or have lived in the Ozarks for generations. Stories have been condensed for length and continuity, and are presented primarily in the interviewee’s own words. Please send an email to Kaitlyn@OzarksAlive.com if you know of someone who would be good to consider as a feature.

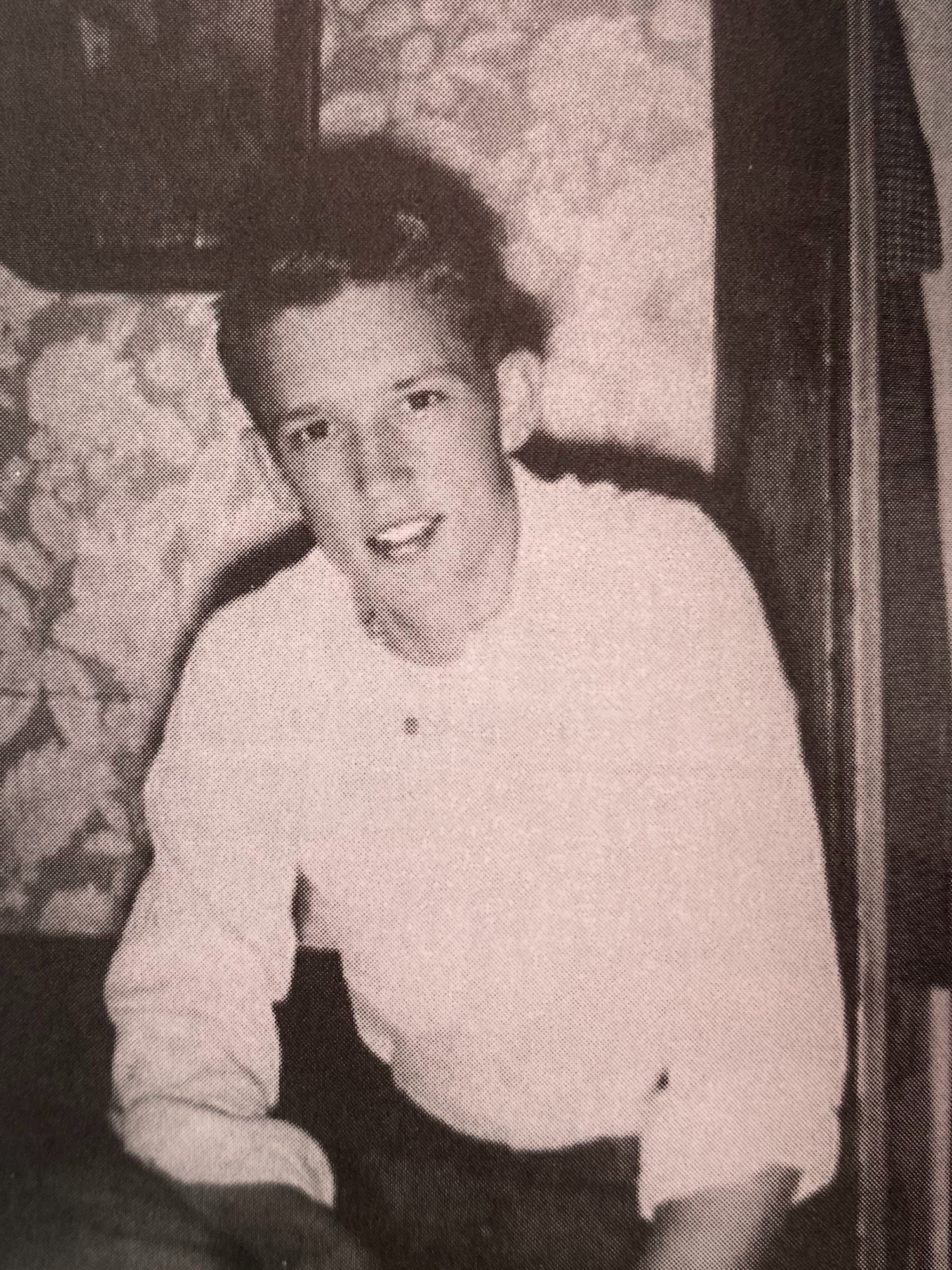

Leon Combs’ life has taken him both right down the road and worlds away from the place he was born. The story might feel paradoxical, but many elements of the 87-year-old’s existence have been beyond the norm, beginning with a horrific tragedy.

That moment did not define the rest of his life, but it did put him in a place where other moments could follow: a rural Ozarks upbringing; time out West as a migrant worker; service in the Marines; a desire to write, which led to journalism school — and a supremely successful career in sales.

It led to innovation in education and agriculture; love and tragedy, and heartbreak brought by its end.

And a decision to come back home and make the place where he began even better.

Combs has a long history of business and influence, but he is best known today as a philanthropist from Bradleyville, Missouri and the author of the best-selling book “Hicks from the Sticks.” The book chronicles Bradleyville’s legendary basketball team that had a 64-game winning streak and had three state championships in the 1960s.

In his words...

“I was born in Forsyth on March 26, 1935. My parents were Joe and Virgie Slone. My mother's maiden name was Combs; she was a Bradleyville Combs.

“My father went to Colorado, to be with his father. I think my father had some drinking problems. He had a good business here at one time, and then during the Depression, he started drinking and got into kind of a bad situation. Later, he wanted my mother to bring me and the other kids and come out.

“It’s like the Joads in ‘The Grapes of Wrath.’ I had a brother, a teenage brother, who got an old truck and loaded all these things up with my mother and my brother, 13-year-old sister and me. I was just a baby — a year old.”

In December 1936, a few minutes — perhaps during a day that previously had felt normal — was destined to change the course of Leon’s life forever.

“My father came home, and my mother was in the kitchen with me; she had been Christmas shopping.

“He put a gun to her head and killed her. And she fell on me, my sister said, then he shot himself.

“My sister said I was screaming and crying and covered in blood.

“They had the funeral there in Colorado Springs. I was taken to California by a relative; it happened to be my sister, who was 20 years older than me. She was married, living in Sacramento.

“They kept me during that winter, but her husband did not want me around. They had already had one child who was born about the same time as I was, and she was pregnant with another one. So they were going to put me in an orphanage in California.”

Then came another key moment in Leon’s life. Shortly before he was to be taken to the orphanage, an aunt and uncle back in rural Taney County, recently married and, with no children of their own, agreed to give him a home.

“They called back to Missouri and talked to my deceased mother's brother, Etcyl Combs. He said, ‘I just got married. My wife and I will take that boy — just send him back to us.’

“So an elderly woman brought me on a train from Sacramento to Springfield in the summer of 1937 when I was two years old.

“At that time, Bradleyville was even more remote than it is now. Obviously no transportation, no conveyance. So the mailman brought me from the train station to Bradleyville.

“I remember none of that, but it all happened.

“I can never complain about my life, even though I started in a very rough way. I probably ended up with parents who were the greatest parents ever.”

It began a childhood in an Ozarks vastly different from today: One of greater rural isolation, with one-room schools, no electricity, but a sense of community built around moments like pie suppers, church meetings and smalltown Saturday nights.

“We would have occasional visitors come. Usually people who have gone to the West Coast during the Depression and raised families out there — they would come back and want to talk about the St. Louis Cardinals. Well, I didn't know anything. We didn't have newspapers, didn't have television. I think some people listened to the games, but I didn't know the players. And that's just one example.

“They had real pie suppers where, when you did the auction, you did not know whose pie this was. But if I liked someone — and I knew that she had a pie up there, although she’s not supposed to tell anyone — and if I could identify which one was her pie, then you could buy it and eat with with the girl. That was the way it worked. And they were raising money for charity work. So we all loved that; that was always fun.

“Church was a big deal. I remember fifth-Sunday meetings, which almost turned me off of religion. Somebody gave my mom a hand-me-down blue wool suit for me to wear. It was one of those old scratchy wool ones, way back when, and my skin is very sensitive. On Sunday, I'd have to wear that suit.

“On fifth-Sunday meetings, they would preach all day long and have dinner on the ground. So they’d start in the morning and have two or three preachers; this one would preach, then this one would preach. Then they’d take a break — and thank God for it. They’d lay tablecloths out on the grass under the trees. Everybody would go eat, enjoy, then right back into the hot church, sitting there, another four or five hours.

“I just remember I couldn't wait to get home to get those things off and get my jeans on. It felt so good.

“When I turned 16, they let me have the car to go to Ava. In these small towns, the guys always had to go to the other town to find a girlfriend. The girls we were raised up with, we knew all our lives and weren’t interested in them. And those guys would come down here.

“The square was a hopping place on Friday and Saturday night. There was no Walmart in Ava, nothing like that. All the businesses around the square, lights were on, and guys had straight pipes on their cars, and would roar up.

“I met a girl named Glenda Jo Walker in Ava. She just loved me, and I loved her. She was 16 and I was 17 — maybe she was 15. She was a really good roller skater, and they had a skating rink in Ava. That was a main diversion for kids, and the Avalon movie theater. That was on the square.

“Glenda Jo was a really good skater. I mean, she was skating backwards, everything. She always kept trying to teach me, and I never could learn to skate. I was too awkward. But we’d go to the movies and then get in our cars and go out and run around. That was our social life. We never had a prom at school. Never had a dance. Probably because of religion. I didn't know what a prom was.

“The things we didn't have really didn’t hurt much, because you didn’t know what you didn’t have.”

During his growing-up years, Leon spent time working at his family’s rural store in Brownbranch, a small community in Taney County. He also made time for school, which was important to his parents — even though they themselves didn’t have more than an elementary education. Those days began early, and for his Dad, not all work took place within the store's walls. Many times, he went to Springfield to get items for the store, or to bring his customers' animals to market.

“My dad would go to Springfield, sometimes five times a week, with a big two-ton truck with high racks on the sides. Local farmers, who were our customers, would say, ‘I've got a veal calf I want to go to the stockyard in Springfield.’ The other guy's got a hog. The other guy's got a cow.

“It would be my job to pick up those animals. My dad would wake me up at four o'clock in the morning — ‘Leon, get up, go pick up a load at Wilbur Johnson’s.’

“So I’d get the truck and head up Caney Creek Road, and hope they’d have a loading chute. Some of them didn't have, so you’d have to go out into a field, and back the wheels into a ditch.

“Those were the days before Walmart, before the big-box store of any kind. People did all their grocery shopping at the country store.

“In those days, you didn't go around and pick your groceries yourself. You told the storekeeper, and they would get it for you. I remember when the first stores started self-service. I couldn’t imagine people just walking around getting their own items.

“We had wood-burning stoves; a cookstove in the kitchen, and a heating stove in the house. It was my job to chop the wood and the kindling. My dad would get up in the morning and make the fire in the kitchen, in the cookstove, and one in the other room in the wintertime. You made a kitchen fire year-round because you had to have one to cook.

“It was my job to be sure that there was wood and kindling in the box, but I remember one time I forgot to do it.

“It was early in the morning — Dad got up at 4 o’clock — he came in and shook my bed and said, ‘Leon, get your ass out of bed and go chop some wood. I'm going back to bed. Chop some wood, carry it in, and build a fire.’

“That only happened about once or twice. I remember almost mentally making a decision that from now on I will never skip that.”

As Leon approached his high school graduation, one of his teachers had plans for his future. Back in those days, Bradleyville’s valedictorian was given a free ride for college. The individual who qualified as that role couldn’t attend so Leon — as the school’s salutatorian — was given the opportunity instead. He attended one year at today’s Missouri State University before heading out to the fields of Washington as a migrant worker, as many rural Ozarkers did in those days. The plan was that he would return in time for college classes, but an unexpected encounter threw his intentions off course.

“I had $600 I'd saved up from my summer work. I was in Walla Walla, Washington, and so I bought a Greyhound bus ticket to come back to Missouri to go to my second year of college.

“The bus wasn’t going to be there for a few hours, so I walked across the street to a saloon. I wondered if I could get a beer yet, because I was only 18 and you had to be 21. So I went in there and sure enough, they served me a beer, no problem.

“I was sitting at the bar next to an old guy with a visor cap on. We talked; he said, ‘You know how to play poker?’ I said, ‘Oh yeah, me and the boys play poker all the time.’ We lived in a bunk house during the wheat harvest. He said, ‘We got a good game back in the back room here if you'd like to get in. You got any money?’ I said, ‘Oh yeah, I’ve got some money.’

“So I went back there, and it was a round table with a light bulb hanging down. Four or five guys sitting around with little caps on and a fifth of Jack Daniels sitting in the middle of the table. ‘Help yourself, son.’ So I reached into my shoe and took out my $600.

“I got in the game — and I got into the Jack Daniels. And I thought, ‘Wouldn't my buddies be proud of me sitting here in Walla Walla, Washington, drinking Jack Daniels and playing poker with these guys?’

“A few hours later, I left there drunk and broke. I lost all the money. I went and got my suitcase; I’d checked it into one of those spaces in a bus station with a combination lock. Got it out and started hitch-hiking. I had a friend in Klamath Falls who worked on the railroad, so I decided I was going to hitch-hike out there.

“I was in Pendleton, Oregon, at like three o'clock in the morning. And a cop stopped me and said, ‘It’s against the law to be hitch-hiking.’ I said, ‘Well, why don’t you arrest me and put me in jail because I need a place to sleep.’

“He took me outside of town and I waited there, and a big logging truck came by. He stopped and picked me up, and I went to sleep immediately. Next thing I knew, he was shaking me and said, ‘Hey, Buddy, you’ve got to get out. I'm going up to a logging camp here. You’ve got to get out.’

“So I got my cardboard suitcase, and got out in the mountains with nothing around. I climbed the fence; I saw a tree with shade under it, opened my suitcase and threw all my dirty clothes down and flopped on it and went to sleep.

“I slept almost all day, and then I got up at the end of the evening. I remember leaning up against the tree, smoking a cigarette, and thought, ‘What the hell am I going to do now? I can’t go home because I lost all my money.’

“I did go down to Klamath Falls and got a job on the railroad for a few months. Then I ended up joining the Marine Corps.”

That led to his three years of service in the Marines. During this time, he met his first wife, Sondra, whom he married in 1957. He also took correspondence courses in writing, which led to the next chapter: Enrollment in the University of Missouri School of Journalism, from which he was graduated in 1960.

While in school, Leon worked a number of jobs to make ends meet. He was a cab driver at night, and later sold stainless steel pots and pans and fine china for Vita Craft. The latter proved fortuitous for his career when, while in the newspaper office one day, a representative for Jostens, a yearbook and school memorabilia company, came in to place an ad for a salesman.

“When I was working for Vita Craft, I became the number one salesman on the University of Missouri campus, and I had 15 guys working for me.

“I was doing very well. I was also working for the Columbia Missourian newspaper, which is published by the University of Missouri School of Journalism, and this guy came in to place an ad for a Jostens salesman. My professor said, ‘You're talking to the best salesman in Columbia.’

“He asked me, ‘Do you want the job?’ I said, ‘Well, how much does it pay?’ He said, ‘Let’s go across the street and talk about it.’ He said, ‘We'll start you out at $150 a week, which is a draw against future commissions.’

“I said, ‘Wow, that sounds pretty good.’

“They hired me, and I started to work for them when I graduated from school at the end of January. I finished school, and went to work the next day.”

Those early years were also filled with life-changing moments on a personal level. There was a move from Columbia to St. Louis. Another came through the arrival of children: Three biological ones, including a daughter who died at eight weeks old from a heart defect. The Combs’ niece also came to live with the family after her mother passed away, echoing the help Leon received in his own life when his parents died.

“It was a big decision for us to make at the time. And my wife — it was her niece; it was her sister’s daughter. I said, ‘Honey, Do we want to do this? She's a teenager.’ I didn't know what kind of trouble we're getting into; 14-year-old girls are not the easiest thing to handle.

“Sandy's mother, the girl's grandmother, brought her to Las Vegas, and we flew to Las Vegas for a few days. And of course, Randi — her name is Randi — was just grieving and crying the whole time.

“We decided to bring her back, and she turned out to be the best kid I had. She was less trouble to raise than either of my own kids — I just loved Randi. She was never a problem. She was always sweet and kind. And an excellent student — very smart.

“I know that someone gave me a chance. And I did talk about that with Sandy at the time. If it hadn’t been for someone wanting to take me in, I certainly wouldn't be here today. So let's do it. And it was the best decision I ever made.

“Randi today lives in New Zealand; she’s going to come and see me here next month. Her kids call me Grandpa. And she tells me every time she sees me how we saved her life.”

And in 1966, Leon made a decision that changed his own life: He joined Alcoholics Anonymous.

“We had moved to St. Louis in ‘65, but we hadn't gotten our house sold in Columbia. So I told my wife, ‘I'm going to go back to Columbia and see what I can do about this house.’

“So I went to Columbia, and instead of selling the house, I went straight to the bar where I spent so much time when I lived there. I stayed there all day and closed the bar that night.

“I remember walking out to my car with one of my buddies. He said, ‘You should not be driving, especially to St. Louis.’ I said, ‘I can drive; I can do it.’

“So I got in my car, and that's just when they were building Interstate 70. It was not complete yet. Some of it was complete, some of it wasn’t. I remember driving 120 miles an hour.

“I almost killed myself. I remember going to sleep and hearing gravel, waking up, and be at the edge of the road. I got home, and the next morning I called Alcoholics Anonymous.

“I was just mad at myself for doing what I’d done. And I decided on the way home, ‘I'm not going to drink anymore. It's ruining my life.’

“I walked into a church basement for an AA meeting. I was scared to death to go to the thing. But I got in there, and after a few minutes, I felt at home. I was among people who had the same problem I had, and they laughed it off.

“I would tell stories about how I was hiding my bottles. They’d say, ‘Hey, we all do that. That’s part of the program.’ I was so relieved that I wasn’t crazy.

“I have never had another drink since 1966. So that changed my life markedly.”

And it shifted his life professionally, too.

“In 1966 I was probably at the bottom of the heap when selling yearbooks for Jostens out of about 1,000 salesmen. In 1970, I was number one in the nation: Total sales, total delivered dollar volume, total commission, I was making $250,000.

“We were at a sales meeting in San Diego and had a cocktail party before the meeting. The CEO of the company … walked over and said, ‘You got me a raise.’ I said, ‘What are you talking about?’

“He said, ‘I told the board of directors that I had a salesman making more money than I was. So they raised my pay.’”

Despite his great success with Jostens, it wasn’t the only chapter of Leon’s professional life. One morning, while listening to the radio, a key interview led to a sale — of yearbooks, and later of the school itself.

“I did well with Jostens. I made quite a bit of money. I saved some money, invested it in various things, just mainly stocks and bonds. Then I was in the car one day in St. Louis listening to KMOX radio. They had a guest who was president of Sanford–Brown College.

“She was talking about how they trained secretaries in those days, and that they taught shorthand and typing and had accounting classes. So I stopped and wrote down her name and called her the next day, and went over and saw the school and sold them a yearbook, and made friends with people.

“Maybe after a year, I was going there and the president said, ‘Mr. Combs, why don't you buy this place?’ I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ She said, ‘Sanford-Brown.’

“I said, ‘How do you buy a college?’ She said, ‘This is a proprietary school. My husband and I owned it. He passed away last year. I don't want to run it anymore.’

“She had about 75 students, mostly girls, doing secretarial work.”

So he did — and soon made some significant changes to grow the school. One was through gaining accreditations. That fact would allow students to receive certain grants and loans, and increase enrollment. It lacked those designations previously, he says, because the former owners didn’t want to accept students who weren’t White.

“I said, ‘Well, that’s going to change.’

“I called friends of mine who were retired PhDs who I worked with in education, fellow CPAs; we got to it right away and got the school nationally accredited in nine months. Then, when we would recruit students, they could get Pell Grants, which would pay most of the tuition.

“This was 1981. We were in a period of terrible inflation, and interest rates were 18 to 20 percent. I bought a five-year CD paying 16 percent a year. So there was great unemployment, nobody could get a job, and everybody was going to school.

“I got an advertising agency to make a big video about Sanford–Brown College: ‘It was a 100-year-old school, and how we train you for jobs, and you get a job.’ I was the first school in the St. Louis area to do advertising on television. At the time, it wasn’t considered something that you would do.”

But it worked.

“We were just overwhelmed. We had a morning session, and another school in the afternoon. We even had a night school.

“So I bought a second campus.”

Which was followed by others until he had five.

“We were training registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, occupational therapy assistants, physical therapy assistants, accountants, computer programmers. And we were just overwhelmed. Students were coming in fast — and then I kept hearing about the need for truck drivers.”

As he has throughout his life, Leon learned by listening and responding. Hearing the need for drivers led him to focus on training for trucking. He opened a truck driving school, a move that once again greatly expanded the business, and ultimately grew to three dedicated campuses.

“I got a buddy of mine, down in Crystal City, Lester Johnson — he and I started the truck-driving school. I got a group of my friends together, and we bought six new Freightliners. There was like $700,000 we had to invest, and we started AMTEC Truck Driving School in Crystal City. Others campuses followed in Granite City, Illinois, and Dayton, Ohio.

“Each one of them, when we got rolling, was graduating 100 students a week. And then trucking companies like J.B. Hunt, Werner Enterprises and Schneider were lined up trying to hire them. We would only let them come to hire the students on a certain day of the week. So it was easy to get students to come in because they could see all these other students getting jobs.

“Most of these guys were handymen who never really had a job; they were unemployed. To get a big $100,000 truck or be paid $40,000 or $50,000 a year was a dream job. So that went really well.

“I made money, but they got a job. I fulfilled my promise. I was sure that we had quality programs. I said we could run a quality, honest program and I can make all the money I need that way. We do not need to cheat, we do not need to lie.”

While there was great success in the 1980s, there was also personal turmoil through the death of his first wife by suicide. By the next decade, Leon’s life was once again headed in a completely different direction. This time, that road took him home to the Ozarks alongside his beloved, Dot.

Ultimately, the couple built a home on Bugle Mountain filled with intentional detail and expansive views for miles over the Ozarks hilltops through 10,335 square feet of finished space. The estate has been the site of various fundraisers, an extension of the couple's work on many charitable boards.

“When I met and married Dot, it changed my life completely.

“She had a beautiful smile. She always seemed to be happy while I tend to somehow see the dark side of things. She would always laugh and say, ‘Oh, come on.’ She had a very positive way of looking at life. The glass was always three-quarters full with her, no matter what. She was just a sweet, kind, loving person.

“We still lived in St. Louis County when we got married, but she wanted to know where I was from, so I drove her down here. When I left here, I said I was never coming back to this place. We didn’t have running water. We didn’t have electricity. We didn’t have anything. But she said, ‘I love this place. We ought to retire here.’

“So that was the beginning of moving down here. We bought about 20 farms, all contiguous. That’s not easy to do, but I’ve got 3,500 acres here.”

“Dot was a very non-ostentatious person, and she thought this place was ridiculous. I said, ‘We’ll use this to raise money.’ We’re both retired and we’re both helping all of these charities. And we’ll use the house for our family, because we have big families with all our kids. We have like 20 grandkids. So when they were young, we’d get them all here — 40 people — for a long weekend. They’d be all over the place.

“This house is more than just a residence for a couple or a man. We used it a lot.”

The acreage also serves as a place to raise his elk — another of Leon’s ventures in recent years, which he reintroduced to Taney County in 1995 through his Beaver Creek Elk & Cattle Ranch. It also offered Leon renewed perspective for writing and connections with his Ozarks roots.

Leon was a neighbor of Birdle Mannon, the legendary Ozarks pioneer whose family moved to the region in 1916 and where she lived, in the same log cabin, for most of her life. After she died in 1999, Leon donated the cabin to Silver Dollar City, where it remains on display today. He’s been a supporter of the White River Valley Historical Society, helping raise money for its museum in Forsyth.

He has also accomplished historical preservation work of his own. In addition to a book of short stories and memories about growing up in the rural Ozarks, Leon published “Hicks from the Sticks,” a book about Bradleyville’s legendary basketball team that had a 64-game winning streak and had three state championships in the 1960s. It was a surprising feat for the town, which didn’t even have a basketball court a few years prior.

“I helped build the Bradleyville gym — they took up a collection to build the gym. It took about $2,000 to build the gym. It had a tile floor. But then they started learning how to play ball. They got a real coach.

“They won the state championship three times during the ‘60s. I lived in Columbia at the time. For the first one, I literally sat in the bleachers with tears running down my face as my brother, Jerry, was the center of the team.

“To see them there and to see them win the state championship — it was just almost unbelievable. And then to see them go on and do it two more times we're going to do it two more times and be recognized all over the state.

“I was selling yearbooks at the time in Kirksville and Hannibal. People at the schools would say, ‘Combs? Combs? Where are you from?’ I’d say Bradleyville. They’d ask, ‘Are you one of those Combs who plays basketball?’

“I self-published the book, but it became a bestseller on Amazon. And it was number one on Amazon for the state of Missouri 18 weeks in a row.”

Life and years have passed, accompanied by moments of both joy and sorrow. A great heartbreak came when Dot was diagnosed with a rare lung condition in 2016, brought on by her beloved pet Macaw, Dude.

“We went to Mayo Clinic in Florida, the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota and Barnes Hospital in St. Louis. The pulmonologist at Barnes Hospital said, ‘You don’t have a bird, do you?’ She said, ‘Yes, I’ve got a blue and gold Macaw.’ He said, ‘You’ve got to get rid of it.’

‘Why?’ He said, ‘Your lungs are compromised from bird dander. Some people are allergic.’

“She cried and cried, but we got rid of Dude. But that didn’t help. Eighteen months later, she was in the hospital dying. I crawled up on the hospital bed and held her in my arms as she died. That was July 23, 2018.

“That was a big blow to me. That’s been four years ago now.”

It’s been nearly nine decades since the day Leon was born a few miles from where he now sits, and life looks different. The days of youth are replaced by moments of reflection. Perhaps it's a life unexpected by the version of Leon from Bradleyville High, who went to work in Washington between college years, and later joined AA, and along the way developed skill and career of connecting that would serve him and the world well. But thankfully, it's one that Leon today looks back at with satisfaction.

“Life turned out to be good. I have no complaints.

“My son just did a video on my life here a couple of months ago. He said, ‘I'm going to show some of this at your funeral. What would you like to say?’

“I said, ‘Well, I have had a great life. I want to thank the Bradleyville community for taking me in when I had no place to go, for giving me a home, giving me a life, giving me a community, giving me loving parents, and brothers and sisters and friends.’ And I said, ‘To those of you who are here for my funeral, don’t grieve. Go out and have a party, because I've had a wonderful life.’”

This story is published in partnership with Ozarks Alive, a cultural preservation project led by Kaitlyn McConnell.