STRAFFORD - It’s amazing to think about how signposts of life can mean such drastically different things to different people and the generations to which they belong. To those who partnered with them in life, old barns and farms and landmarks tell of lives lived — while, to others, they silently say, “You’re too late.”

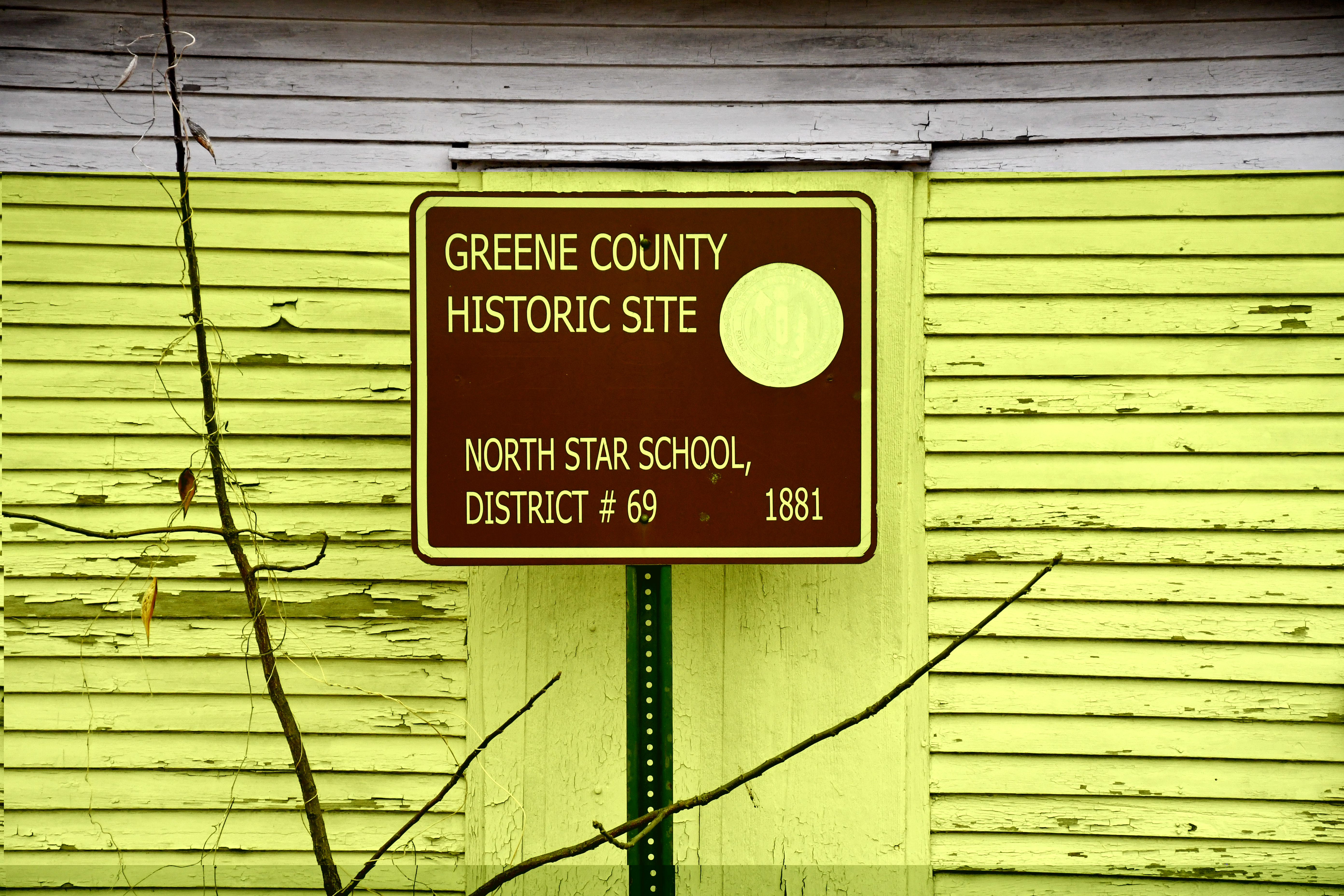

Such thoughts have long traveled in my mind as I explore our Ozarks roads. One particular example is in Strafford, where a little white structure with peeling paint is tucked away along a street. It didn’t need to speak, but still said it was a school: One side of windows (more on that in a minute) and a belfry told the story — which was confirmed by a Greene County Historic Site sign out front.

It told me that the building was formerly the North Star School, but that wasn’t enough for me to know.

What was its story? What is its future?

One teacher for one student body

After doing some research, which told a bit more, I reached out to Martha Smartt, city administrator for Strafford, to find out who was best to speak about the school. She directed me to Steven Bodenhamer, who was gracious enough to meet me there on a chilly morning that felt like spring had stood us up.

He opened the creaky wooden door and we went inside the small building. Near the turn of the 20th Century, around 70 students were enrolled in this one school, and expected education from just one teacher.

“There is a county superintendent’s report that said, ‘They need two teachers real badly,’” says Bodenhamer of the school in 1909.

The school, Bodenhamer says, goes back to the 1880s. At one time, it was one of more than 120 rural districts that dotted the rural Greene County landscape, drawing students for education, Grades 1-8, in the small building with windows on one side.

“You notice all the windows are on the left. When the one-room schools were originally built in the late 1800s, windows were evenly distributed,” says Bodenhamer. “In the 1920s, early ‘30s, educational research determined, since most people are right-handed, that the light should come in over the left shoulder. Therefore, the windows were moved. If you look at other one-room schools that were in operation in the ‘30s or later, you'll find windows all on the left side.”

There were other changes with time, too, Bodenhamer says. In the 1920s, students desiring a high school education were able to go on to Strafford, with North Star paying the tuition – a necessity since it was technically an out-of-district transfer, even though the one-room school only went to Grade 8. A drastic improvement to the arrangement came the next decade, when bus transportation was also provided for those students.

School lunch at North Star

Another shift in time is seen through a door near the entrance, where a tiny space holds the remains of a kitchen, complete with a sink, range and refrigerator.

“In the 1930s you started seeing some subsidizing of school lunches. That was brought out through the draft of World War I, finding a lot of young men suffering from less than adequate nutrition,” says Bodenhamer. “So this was not a cafeteria like the schools operate today. The commodities were furnished – beans, applesauce, vegetables, so on. And the teacher would fix lunch.”

According to a document titled “North Star School Brief History” that Bodenhamer shared with me, the school was merged with Strafford C-2 and became known as the new Strafford Reorganized District No. VI. North Star remained open under the new arrangement through the 1951-52 academic year, and then it closed.

After its students were sent to other larger districts, the Women’s Progressive Farmers Association purchased the building in 1953, and it was moved to Strafford to be used as a clubhouse. It served the club, and as a hub for community events, for around 50 years.

But as time ticked to the 21st Century, and the membership of the club dwindled — while ownership of the school remained — its future became a concern. There was fear that with the deaths of club members, the former school would potentially be turned over to the state government and be put up for sale.

A museum for Strafford's past?

A few local folks organized a non-profit — Strafford Historical and Preservation Society — and bought the building from the club in 2006. The school isn't their only preservation effort, but a significant goal with the purchase was to open it as a museum.

“Long-term plans for the property include future use of the adjacent lots for a Strafford area history museum with the North Star building as a focal point, according to society president Steve Bodenhamer,” noted the Springfield News-Leader in 2007.

That Steve Bodenhamer is the same one who stood in the school with me that day. His interest in the project has remained in the 15 years since that article ran, even though the road has perhaps been a bit rockier than expected.

A new floor has been placed, and the exterior has been repainted — the latter which Bodenhamer says will take place again this summer. Another note of dedication is the belfry, which has been outfitted with the original bell that Bodenhamer helped buy back for the school at an auction. While the school has been opened periodically in the years since for community events, and preservation has taken place, the museum dream is still a goal to achieve.

“Now the thing that's kept that from happening has been voluntary manpower – and finance. We have strived to maintain the building. It is one of about four remaining one-room school buildings in their original condition left in Greene County,” says Bodenhamer.

Those things are a common problem with regard to rural school preservation, says David Burton, county engagement specialist with University of Missouri Extension, who has done significant research on the history of Greene County rural schools.

“People have a little bit of a romantic memory of one-room schools, so sometimes people just have a love and affinity for keeping them around and restoring them,” Burton says.

Those feelings, however, do not mean that there is funding available for their restoration or preservation. Grants are often mentioned as a path for historic preservation — but they’re limited, and typically come with strings attached. That type of funding is also less available to sites that are loved in the minds of those who knew them, but not connected to a widely significant historical message.

“Not every not every building is as historically important as another. Just like, you know, not every politician is historically important, either. It's the way that that's distinguished,” Burton says. “We had a lot of discussions about that when I was on the historic sites board – trying to have criteria about what qualified for the board and what didn't. We tried to kind of follow those state and national criteria as best we could. Otherwise, you end up just adding things because someone has the warm and fuzzies for it, or the right person is advocating for it. If you really want the list to be a list of historical significance, you wanted to have some criteria, right? So not everything can be on that list.”

Of course, regardless of widely recognized “historical significance,” another key factor in preserving these one-room schools and other structures is simply that they are important to the people who want to see them survive.

Sometimes those reasons are practical — when buildings are turned into community centers, for example — and at others it’s nostalgic. When it comes to schools, it seemingly becomes a greater challenge as more and more people who experienced them firsthand disappear.

“The few people I can think of that I've talked to that are still living that went to one-room schools were in like first or second grade when the school consolidated or closed,” Burton says. “You're not too far away from not having any of those people. I think what it requires is someone passionate about the idea, passionate about the school, passionate about the history.”

That is the case for Bodenhamer, who has deep ties with the region. He didn’t attend North Star School, but grew up in the area and had a multi-chapter career as an engineer in Oklahoma before moving home, working with City Utilities and as city administrator in Strafford, as well as in Battlefield. Bodenhamer also has long had an interest in local history, which in the school’s case is personal: his grandmother was educated within its walls.

“Knowing this is one of the few structures left in the county, I didn't want to see it destroyed,” he says. “My grandmother went to school here from 1898 through eight more years, which would be 1906. So there’s quite a bit of connection there.”

For others, time makes those ties fray.

The school’s long-term future is secure in one way: the nonprofit will retain ownership of the building in perpetuity. However, the school's social significance isn’t something Bodenhamer or the school’s board of directors can secure alone. Like the WPFA members, the board’s manpower has come sort of full-circle with regard to the age of those involved in the project.

“We have a board of directors that has, I think, seven people on it. And they range from late 50s to 90,” Bodenhamer says. “We need another generation.”

Want to learn more?

Steve Bodenhamer would love to speak with anyone who wants to help with preservation efforts at the school. He may be reached at 417-766-0512.