This story is published in partnership with Ozarks Alive, a cultural preservation project led by Kaitlyn McConnell.

NEVADA - The peaceful, green grassy plot looks empty, save a sign that tells passersby where they are: The Nevada State Hospital Cemetery.

Those few words are accurate, but they don’t say everything. They do not tell the stories of the hundreds who are buried there, kept under lock and key in death as they were in life. Their remains — and in some cases, perhaps even their names — are lost in the ground and the past, largely without stones to mark their existence.

It was several years ago when I first found the cemetery around a half-mile from the edge of Nevada, a town known for its role as the Bushwhacker capital during the Civil War, resulting in its being burned to the ground in 1863, and as home to Cottey College, a women-only institution which began in 1884.

For around 125 years, the Vernon County seat also was long known as the location of Nevada State Hospital #3. The facility was one of few hubs across Missouri for the “insane,” a term often used in its early years. It swelled to a peak of 2,185 patients in the 1950s and was a significant source of local employment.

As models of care changed, including the advent of psychiatric medications, the hospital’s size gradually reduced before closing in 1991. In the years since, much of the ornate and iconic campus has largely disappeared.

But away from the edge of town, the cemetery remains — and reminds of stories that probably were largely never known, and today never will be.

Construction of the hospital

After that first stop, I never forgot the cemetery, but a desire to learn more turned into years of good intentions. While spending more time in Vernon County in recent months due to a project with the Missouri Folk Arts Program, I drove back by the cemetery, and it hit me again: I need to learn more about this.

Sites like this cemetery — where lives feel forgotten — deeply move me. I felt the same a few years ago when researching the Greene County Poor Farm, where residents today lie in unmarked graves. It feels tragic that even though a marker doesn’t speak to a person’s being, it at least easily connects us with who they were, and that they mattered.

Such sentiments led me to the internet, where I began to read about the history of the hospital, which opened in 1887 and in its heyday was larger than many Ozarks communities. Like its original foundation, which was nearly a mile in length, the hospital's story is long and complex and can’t be done justice with one article.

Plans began percolating for the facility in the 1880s, when newspaper reports tell of a bill in the Missouri state legislature to appropriate $200,000 for the construction of a new mental institution, joining previous locations in Fulton and St. Joseph. The bill passed, and a committee was formed to decide on an appropriate site — of which Nevada was not the only possibility.

According to “Nevada State Hospital #3,” a book about the hospital’s history, Springfield was originally the intended site for the institution. This ultimately changed: It could be located anywhere in the southern part of the state, legislators decided. Competition was apparently fierce, given the potential economic impact such a hospital would have on a community.

“There is too much feeling manifested in the contest for the location of the State lunatic asylum, No. 3,” noted the St. Joseph Daily Gazette in July 1885. “Either of the flourishing cities of the Southwest that have entered the lists can live without the asylum, and the county in which either is situated would be better off without such an institution. Let us have peace, brethren of the press in Springfield, Nevada and Carthage. Somebody has to be disappointed occasionally.”

Nevada was in it to win it. In addition to ongoing support in the local newspaper, the book notes “a regular canvass was conducted, public meetings were held and considerable sums subscribed even by farmers living at a distance from Nevada. At last, an amount aggregating about $30,000 in money and lands was secured.”

A few weeks later, Nevada prevailed as the chosen site. (A random side note: Could Springfield have had this loss in mind when the United States Medical Center for Federal Prisoners — known locally as Fed Med — was sought in the 1920s?)

Work commenced on the hospital, which was built on 500 acres of land donated by local residents. Before it was done, plans were expanded to include three additional wings, bringing it to three stories high and a frontage of 1,200 feet.

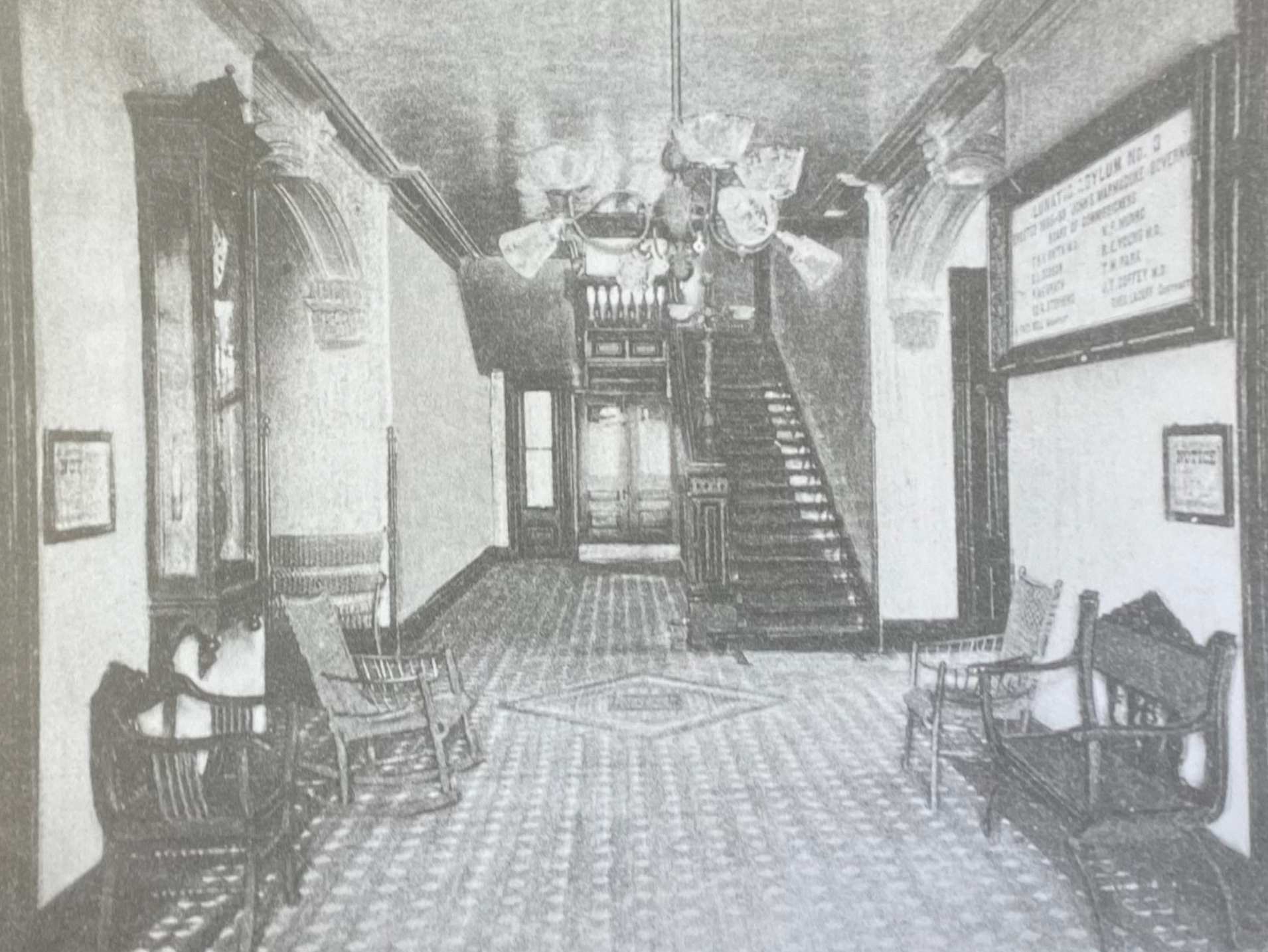

“The new asylum building, as will be seen from the excellent view of its front elevation, in strict keeping with the demands of this progressive age, it being strikingly beautiful (a blending of French and Florentine architecture) and gives evidence of careful study and great skill in its conception,” noted an article in the Nevada Noticer in 1886, while construction was underway. “It will embody every modern appliance and convenience which experience dictates as necessary for the security, health, comfort and happiness of its inmates.”

It was officially completed in 1887, beginning a multi-faceted legacy. One reflected the workforce, of which the hospital’s significance was great; another was regarding the size and scope of the facility; and then there were the patients, who received different types of care tied to the beliefs of the day.

At one time, the hospital had a dairy, garden, hennery and hog farm, as well as handiwork, mattress and broom production facilities, all which contributed to the hospital’s ability to be self-sufficient. These efforts were powered by patients, who were unpaid.

“There is ample proof that this benefited both,” notes “Nevada State Hospital #3.” “For the clients, it offered what was seen as therapy and an opportunity to develop skills that could be used as a vocation after a client recovered and was released. The production departments obtained a larger work force and gained greater productivity.”

Treatment of patients

When the Nevada hospital was built, it was part of a growing movement tied to the work of Dorothea Dix, a national advocate for mental health services who pushed for the establishment of hospitals — as opposed to keeping the mentally ill incarcerated.

“(She) found that there were guys that were in prison and there was really something wrong with them,” says Kami Jones with the Glore Psychiatric Museum in St. Joseph and who also serves as its historian. “They didn't really belong in jail; they needed help, and they needed care.”

Another individual relevant in this effort was Dr. Thomas Kirkbride, who wrote “On The Construction, Organization and General Arrangements Of Hospitals For The Insane.” The book, published in 1854, advised on the physical layout of buildings in which patients were housed. His work influenced the Nevada hospital, which was designed by local architect M. Fred Bell in a massive “gingerbread” design.

“Kirkbride developed what the buildings should look like, and Dix advocated for these gentlemen to be moved into a state-run facility that was more like a hospital and a place where that could get well rather than a prison itself,” says Jones, speaking generally of a historically progressive attitude toward mental health care. “That's kind of where it started. It sort of snowballed and grew from there as becoming a place where you could bring any family member if there was something wrong with them, rather than just (someone who was in) jail.”

Jones’ role is specifically tied to the former St. Joseph facility, but I spoke to her for this story because I think her knowledge is relevant. Given that Nevada was also a state hospital during this same period, it’s likely there were similar approaches and attitudes — which are much different than today, especially when it comes to treatment.

“You have to keep in mind they were working with the scientific knowledge that they had at that time, and it was just very minimal,” says Jones. “They were trying to do anything that they could. If you go clear back to some of the first treatments, they were trying to do blood-borne disease treatment, so you have your leeching and bloodletting and blistering of the skin — all of these things that were basically blood-borne treatment because they didn't know anything about a disease of the mind.”

Seen through a 21st-century lens, the psychiatric care of that day and time sounds more like torture than treatment.

“We knew it was a problem, but we really didn't know what to do for it,” said Dayna Harbin, system director of Psychiatric Services at CoxHealth, to Ozarks Alive in 2020 regarding early mental health understanding. “They did insulin shock and ice baths, and just kind of whatever anybody thought of. ... They would tie them in chairs and just cut a hole in the bottom of the chair and just put a pot down there and leave them in the chair for days and days.

“They would put things over their heads ... so they couldn't see. They did some sensory deprivation. Treatment was much more like you would treat a prisoner in a time when prisoners were treated (poorly).

“I think the restraints and those types of things — they just had no other idea what to do. Because there was no treatment, (the patients) would become extremely psychotic.”

She speaks of depression, which was not recognized as a legitimate mental health need, as well as a misunderstanding of schizophrenia, a mental disorder that causes people to interpret reality abnormally.

“There was and, sadly, still is a little bit of a belief that those people were demon-possessed,” says Harbin.

Why were people there?

Lack of understanding also led to a laundry list of reasons people were admitted for psychiatric care, and by whom.

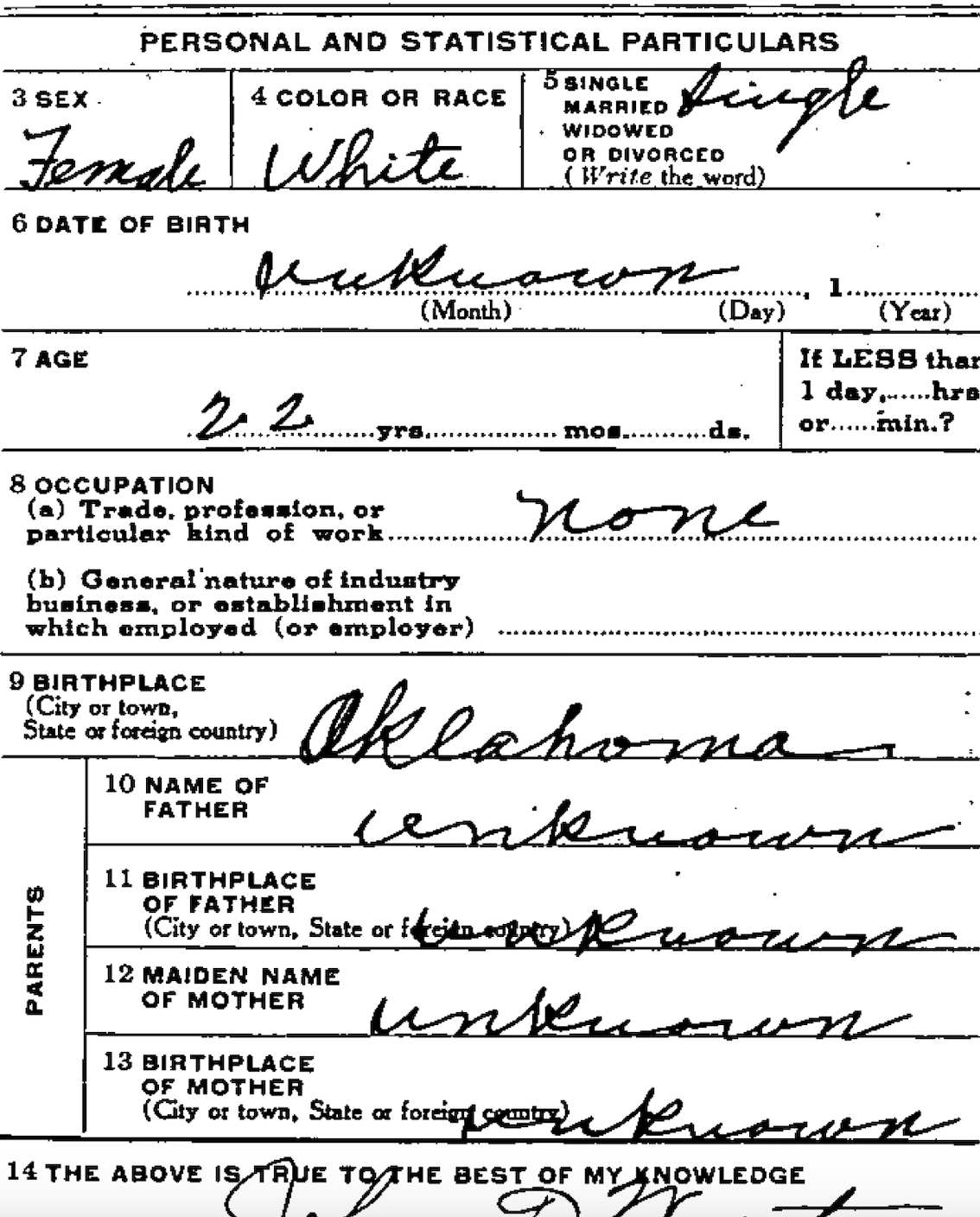

They could be sent there by leaders from their home county, such as Dade County reported in 1894, paying $929.33 for the care of its 17 “inmates” at the Nevada hospital. Speaking generally, family members might decide that an individual was acting strangely — perhaps by neglecting basic hygiene, Jones says — and bring them in for treatment. It was a reality so stigmatized that people’s true identities might be concealed.

As time passed, hospitals began accepting patients for an even greater list of issues until, eventually, “it was basically a home for anyone who didn't quite fit into society or (who they thought) needed to live on the outskirts of society,” says Jones.

It’s true that patients did “recover” and were released throughout the Nevada hospital’s history, but that wasn’t always the case. For some, care — and for whom treatments made their health no better and perhaps worse — became largely custodial.

One example is noted in “Scenes from the Past,” a book about Nevada’s history, which mentions Ward 22, where 47 patients had spent most of their lives locked away. It led to “Operation 22,” a staff-led project in the early 1980s to improve those patients’ lives.

“An effort was made to acclimate these people to a normal environment by making use of the facilities of the hospital and the community,” notes the book. “They were taken on shopping trips, to shows, picnics and parties. It was not long before Ward 22 became an open ward and for the first time some of the patients were able to return home for visits.”

Perhaps the hospital’s most famous patient is James Edward Deeds, Jr., who entered the hospital as a teenager and spent most of his life within its walls. He ultimately achieved fame through sketches he created while at the hospital, resurfacing decades after his death, that were heralded as folk art and published in book form.

Deeds grew up in Ozark, and newspaper accounts tell of tension between his “fierce disciplinarian” father who perhaps didn’t understand his creative son. The conflict between the two was so great that Deeds’ mother had a cabin built for him to live separately from the family, but things boiled over when 17-year-old Deeds threatened his brother with a hatchet. Whether the threat was real or not is unknown, but it resulted in his admission to Nevada’s hospital.

“When Edward found out, he went into the barn and drank engine fuel, trying to kill himself,” a 2011 Springfield News-Leader article about Deeds learning he was to go to Nevada.

He spent nearly 50 years hospitalized in Nevada. Unlike some other patients, he wasn’t forgotten by his family, who visited him — except his father, who reportedly never did.

Even though he had been committed for life, Deeds was eventually considered no longer to be a threat to society or himself, the News-Leader article noted. He was transferred to a nursing home in Ozark in 1973 and, after suffering a heart attack, died in 1987.

Changes in care

Facilities like the one in Nevada began to decline, Jones says, with new laws regarding the work that patients were allowed to do while hospitalized. Another huge shift occurred when psychiatric medications became more available in the mid-20th century.

“A change in the treatment and care of the mentally ill was a long time in coming, but when it did every facet of mental health was revolutionized,” notes “Scenes from the Past.”

“Dr. Paul Barone, who has been superintendent at the Nevada institution for more than 20 years, believes the first real breakthrough came in the early 1950s with the discovery of tranquilizing drugs. Noisy, screaming combative patients were changed almost overnight to quiet, orderly people. These drugs, together with other great advances in the field of psychiatry, have completed changed the lives of nearly every patient in the hospital.”

While on a diminishing scale, the Nevada hospital continued operation until 1991. At that time, plans to shutter the hospital were announced as part of statewide cost-cutting efforts. It was a huge shift for the town, given the magnitude of employment the operation had offered for so many years.

“The (Missouri Department of Mental Health) has to cut $30 million from its budget, and the hospital and habilitation center are in old buildings that are costly to operate,” a department spokesman told the News-Leader in June 1991.

But even after it closed, hundreds of patients remained outside of town at the hospital cemetery. Because death, too, was part of life at the hospital. In 1901, the book on the Nevada institution says exhaustion was the second-leading cause of demise for its patients.

“Those ill-defined, exhaustion categories ranged from ‘general’ to ‘maniacal; and during the reporting period of 1899 to 1900 exhaustion was the reason cited for 41 of the 108 deaths in Nevada,” its pages note.

Communicable diseases were also a problem in the congregate settings, as well as other reasons tied to the patients’ other conditions.

For those without family or resources, up to 1,700 were buried at the hospital cemetery.

In addition to the aforementioned books and newspapers, I discovered more of this information after finding a website for the Nevada State Hospital Cemetery Preservation Group, which was formed several years ago in an effort to reclaim the site’s stones. I also learned of Linda Chestnut, who worked at the hospital herself and was tied to numerous hospital preservation efforts, including the aforementioned history book.

“History is being lost every day,” note the book’s acknowledgments, which perhaps she penned. “Hopefully with the many contributions of stories, documents and pictures gathered in this book, we have been able to preserve a small portion of it.”

I was very excited to learn of Chestnut, a key source for historical information about the hospital due to her personal connections and research. It wasn’t long, however, before this excitement switched to disappointment chased by a reminder: When I find a story I want to share, don’t wait.

Chestnut died in January — of just this year.

Learning about what’s left

I step out of my car on a sunny day in April and head into the offices of Southwest Community Services in Nevada. Part of the Missouri Department of Mental Health and the Division of Developmental Disabilities, the Vernon County facility is the most current provider of local mental health services, and home to what records remain of the cemetery.

After signing in, I meet Savannah Hampton, staff development training manager for SWCS, who I first interacted with through the office’s Facebook page when I inquired for info about the cemetery and its records. We’re soon joined by Chris Baker, SWCS’s director who has been connected with the local care efforts since the ‘90s.

Although their offices are located in a different era and place from the original ornate facility, the past isn’t too far away.

“I bet we get one or two requests a year, looking for a family member or doing some other type of research,” says Baker. But the duo notes that the information available is limited.

When it comes to general historical items, they do have a binder of photos and postcards. A large stone sign for the former hospital leans against the wall, which was rescued from a barn when leaving the former site, much of which was demolished in the late ‘90s.

“I scoured every nook and cranny — I had my feet in places nobody had been for decades,” say Baker, not wanting to leave any historical artifacts behind. “We found that granite sign under a pile of folding chairs and other junk.”

“I actually spent weeks cleaning it up with a razor blade.”

A few other pieces of furniture survive throughout the building; a cabinet, framed blueprints, and a large mirror, visible in early photographs. A clock, which also shows its face in images of the past, stands across from Hampton’s office and was recently restored.

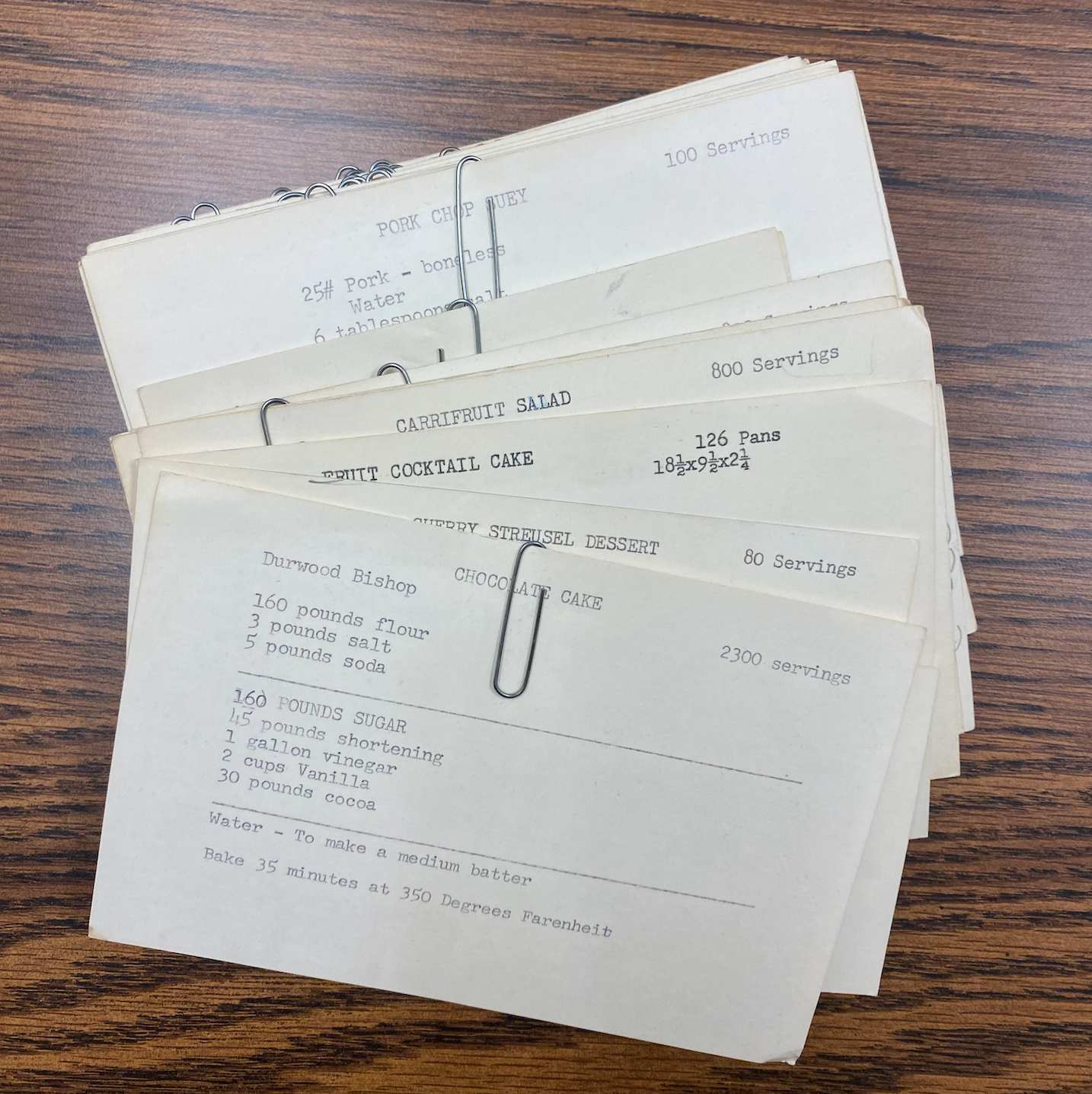

Stepping inside, she pulls collections of notecards off of a cabinet. In old-fashioned type, they tell of how to make dishes in significant quantities: Chocolate cake for 2,300, pork chop suey for 100, carrifruit salad for 800.

Meals in those amounts will never be made again.

Baker and Hampton share about the shifts in mental health and disability care since the hospital was open. Instead of congregate settings, their clients are integrated into society as much as possible. They’re housed — with professional support — in homes throughout the community.

Many of these patients receive care in this setting for years. Perhaps they are seen as too difficult to care for at home. Maybe they stay with their parents through adulthood, but the parents die and the individual has no one to care for them. Given the typically long duration of support, the relationships developed between patients and caregivers are deep.

“We’re the only family a lot of these folks had ever known,” says Hampton. “That’s just how it is.

“There’s still shame and stigma.”

And although it’s not frequent, there are still instances when those deaths occur in care, leaving arrangements to Baker instead of family.

“We typically will have a memorial service,” says Baker, noting at least some loosening of attitudes in some areas with approval from family: “We wouldn’t even put an obituary in the paper for our clients at one point in time. That’s not the case now.”

Those individuals, however, will not be buried at the state hospital cemetery. The last recorded burial took place in 1956, and Baker says it’s unlikely it would ever be used again. A local funeral director has provided plots in the case where someone didn’t have the funds to purchase one.

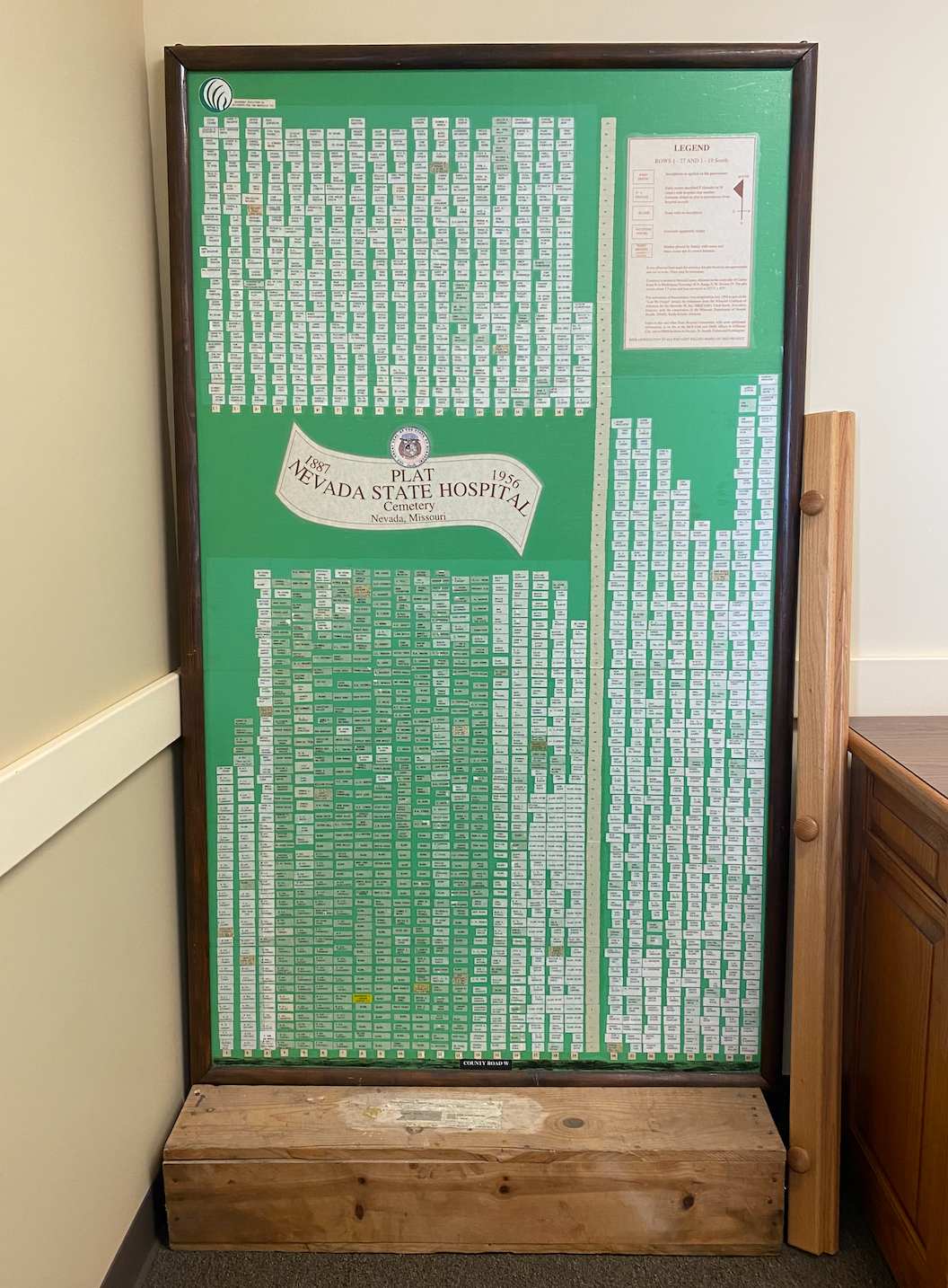

Such efforts stand in contrast to a map of the state hospital cemetery, which leans against the wall in the office. It was created in the early 1990s as part of a mapping process to document names and graves after the cemetery records were lost years ago.

Some spots are blank. Others have names, typed on small pieces of paper and taped in place.

Perhaps the ones with names are more difficult to see since death certificates show, in some cases, how little is known.

Visiting the cemetery

Looking from outside the fence — which is secured with a lock and chain — it appears to be simply a blank field. There were allegedly stones for all graves, although it doesn’t appear that way today.

Given that many were placed without a cement base, most have sunk into the ground while others have become so worn that names are illegible. Some, however, can be seen; I assume these must have been restored in previous efforts.

The cemetery is currently overseen by Missouri’s Office of Administration, Hampton says, and has apparently been locked for some years. (I should note: I’ve been there numerous times in recent months and it was locked every time, so I assume it still is.)

It’s unclear why that’s the case; outreach to the department went unanswered.

After my most recent visit in late April, I have a suspicion as to why. The stones that are sunken into the ground may have contributed to a pothole-like surface. It’s my guess that the state is worried about someone falling on their property.

Seeing the cemetery, it’s difficult to imagine the many stories barely beneath but in a completely other place. Those who were committed unfairly; those with conditions we didn’t understand in those days. Those who died and who didn’t have anyone to care. Those who were intentionally forgotten.

Even though we can’t know them, let us remember them all.

Resources

“Asylum No. 3,” The Kansas City Star, April 11, 1887

“Coal, coal, coal!” Nevada Noticer, June 22, 1893

No headline, St. Joseph Daily Gazette, March 29, 1883

No headline, St. Joseph Daily Gazette, July 7, 1885

“Jefferson City,” St. Joseph Daily Gazette, May 24, 1885

”Kirkbride, Thomas Story,” Virginia Commonwealth University Social Welfare History Project

“Miscellaneous items,” St. Joseph Daily Gazette, Feb. 2, 1891

“Nevada asylum commissioners’ meeting,” St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat, April 12, 1887

”Nevada officials to fight hospital layoffs,” Terri Gleich, Springfield News-Leader, June 29, 1991

”Nevada State Hospital #3,” Employee Relations Committee, 2013

”Mystery artist from the Ozarks is recognized,” Julianna Goodwin, Springfield News-Leader, July 10, 2011

”Remembering the history behind Bushwhacker Days,” Jason Mosher, Nevada Daily Mail, June 8, 2013

”Scenes from the Past (of Nevada, Missouri),” Betty Sterett, 1985

”State Lunatic Asylum No. 3, now in course of erection at Nevada, Missouri,” Nevada Noticer, March 25, 1886

“The County Court,” Greenfield Vedette, Nov. 15, 1894

“The Nevada State Hospital,” The Southwest Mail, March 13, 1903

“With Just Pencil And Paper, A Patient Found Escape Inside State Hospital No. 3,” NPR, March 26, 2016