This story is published in partnership with Ozarks Alive, a cultural preservation project led by Kaitlyn McConnell.

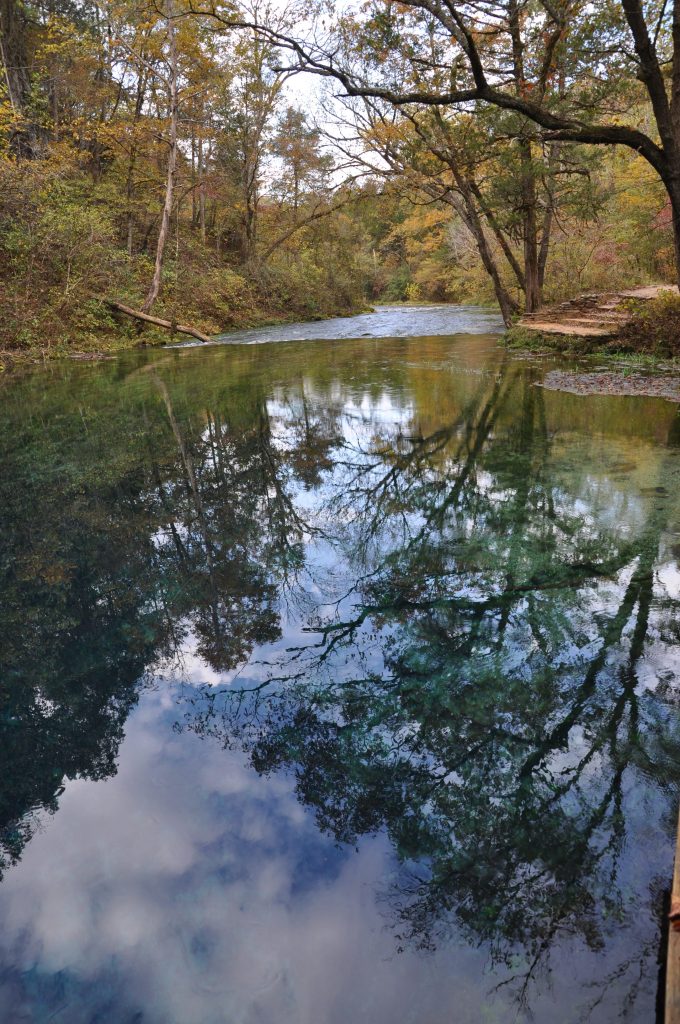

VAN BUREN - Stories converge in the waters of Ozark National Scenic Riverways, a place of stunning natural beauty — and deep complexity, regardless of how much it’s rained.

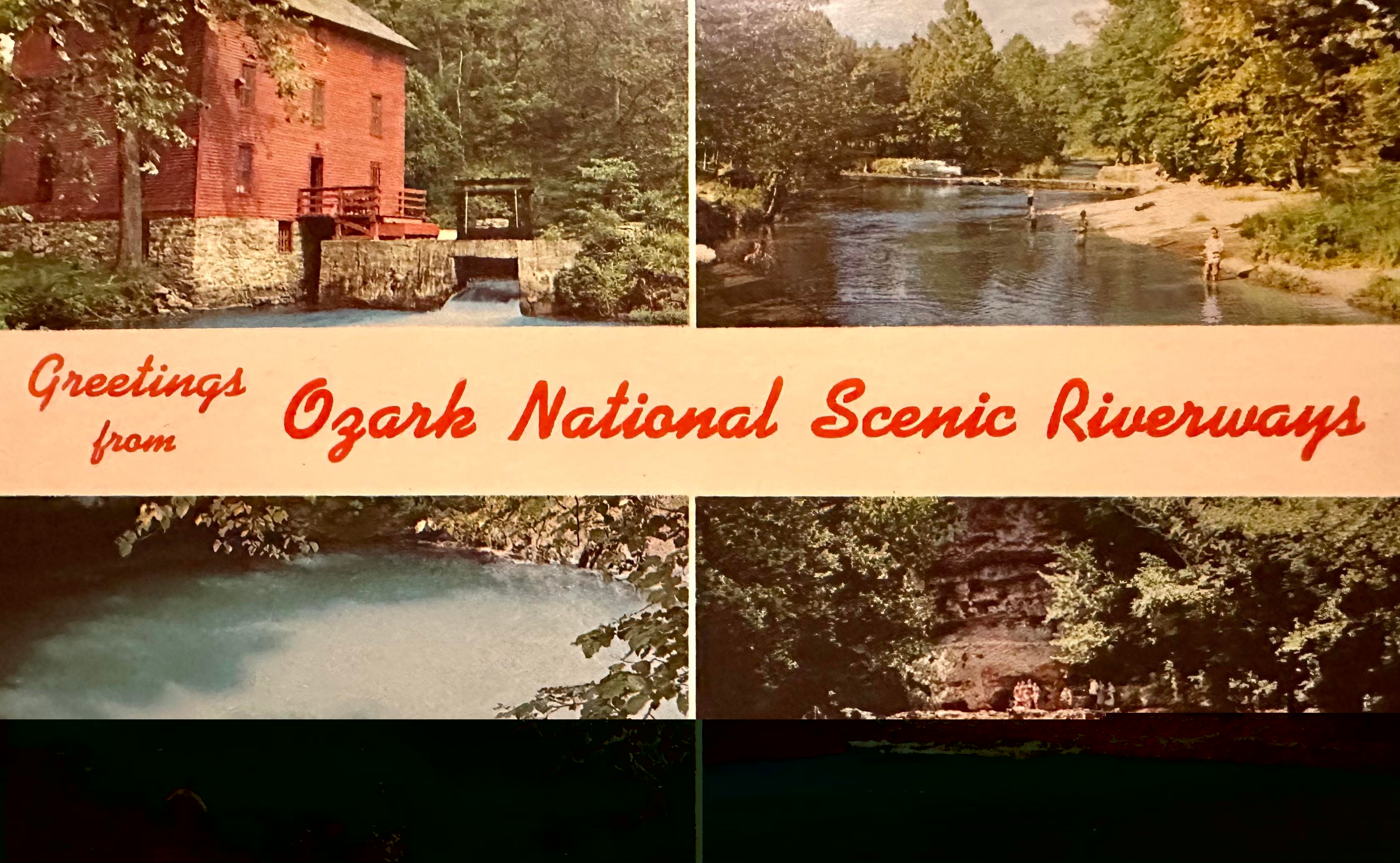

The Current and Jacks Fork rivers have been a source of admiration for generations. Visitors traveled to the eastern Missouri Ozarks to float and fish in the serpentine, sparkling waters long before they were recognized as the country’s first national scenic riverways system in 1964.

Today, more than 1.3 million visitors annually visit the park, which is managed by the National Park Service and features 134 miles of free-flowing water within 80,785 acres. And closer than maps in their hands are opinions and competing priorities, fueled by differing senses of ownership tucked in their hearts.

There are visitors, who come expecting a specific, scenic experience. There are locals, whose deep-rooted family trees make the rivers feel like their own — because for some, they once were. And at the foundation, there are the needs of the environment: The protection of natural resources, and the balance of cultural heritage, both of which represent pieces of a never-ending story.

At the end of the day, the person responsible for managing those various needs, desires, expectations and growth is Park Superintendent Jason Lott.

Lott sits behind a desk at the park’s headquarters in Van Buren. The town is located near the southern tip of the riverways system and is the seat of Carter County, a sparsely populated place with only around 10 people for every square mile.

As with so many of our lives, Lott didn’t expect to end up here: in Van Buren, in Missouri, or even in the NPS. Growing up in Louisiana, he spent time outdoors — “Waterways were always fascinating to me,” he says of things he saw with child eyes — and even at an early age he was drawn by the allure of the past.

“Really, old barns and old houses and the stories that surrounded them were of personal interest,” he says.

Time and a combination of those interests eventually formed a foundation for his future. During 20 years of service in the Army National Guard, he earned a master’s degree in history with an emphasis in Cultural Resource Management from Northwestern State University.

Lott planned to stay in Louisiana, but challenges with grant-funded positions led him to take a job with the NPS in 2002. The decision took him to stints at Lyndon B. Johnson National Historical Park in Texas, Casa Grande Ruins National Monument in Arizona and Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico.

In January 2020, he was hired as interim superintendent of ONSR. Later that year, the title was made permanent.

“Jason is an exceptional leader and he will work to develop strong relationships with the local communities and park stakeholders,” noted Bert Frost, NPS regional director, in a news release announcing Lott’s hire.

While his previous parks helped Lott learn to lead — he served as superintendent at the latter two locations — they were different experiences than what awaited him in the Ozarks.

Before the park

When Lott arrived at the park three years ago, his work built on centuries of history.

Humans have been within ONSR for millennia, perhaps dating to 7,000 or 8,000 B.C. Many years later, Native Americans walked the land. They remained in the area through the early 1800s, after which they largely left or were removed in light of the Louisiana Purchase and white westward migration. Later that century and into the next, the rolling hillsides saw thousands of workers bringing a timber boom to life.

By that time, the area was also well known for its scenic beauty.

In 1925, Big Spring, Round Spring and Alley Spring — the latter anchored with its mill, which found greater success as an icon than grinding wheat — were three of the first sites in the Missouri State Parks system.

The next decade, visitor Ward Allison Dorrance wrote “Three Ozark Streams,” a journal-book that shared his trip along the Black, Jacks Fork and Current rivers in near poetry-like prose:

“To feel the boat settle into the long v-shaped approach, viscous, silent, eager; to paddle vigorously an instant along the inside bank where the water is sharp-toothed, hissing; to shoot down a lane of white-caps (standing erect in the prow, my field of vision filled by the rush, by the foam of the broken river); this is to experience a moment of absolute and exquisite excitement — joy by which afterwards I may gauge the importance of much else.”

While some places in the area were publicly owned by this time, much of the region was in private hands.

Just two examples: In the Shannon County community of Akers, Mt. Zion Church wasn’t even organized until 1938. The nearby town of Cedar Grove, too, continued to have a school and business district through the mid-20th century.

Such private ownership brought the park to a contentious start. Plans to protect the rivers began in the 1950s, which became official in 1964 and culminated in 1972 when Tricia Nixon Cox, daughter of then-U.S. President Richard Nixon, came to officially cut the ribbon on ONSR. It was the same year that the Buffalo National River in neighboring Arkansas came to be designated.

Despite the jubilation expressed by dignitaries at the park’s completion, those with deep roots in the region had not universally found the same joy. Newspaper accounts from the time note just 16 percent of the land in ONSR was publicly held before the park began. While there were some locals who supported the proposed park, many landowners spent years expressing upset, fear and outrage over the pending change.

Perhaps one example that stands out came in 1961, when a newspaper told of a member of Congress being hanged in effigy on the Shannon County courthouse lawn and thrown in a coffin.

The decades since have scabbed wounds, but for some, they remain scars. As longtime local Judy Maggard Stewart recently put it, “I was 11 years old when the man from the park service brought the papers to serve on my dad for eminent domain. I have a very vivid memory of that night because let me tell you — my family loved Akers and we never wanted to leave.”

Such feelings are still relevant in Lott’s work, a factor he freely shares.

“Congress made a decision, the state of Missouri made a decision, on how this place would be created. National Parks got handed that, and we did it,” says Lott. “Various levels of those memories are still fresh of how that happened. Some of it was very amenable and people were interested; it actually served a good purpose for some people who were struggling financially; there was an opportunity for someone to come in and acquire the lands.

“For many others, they (already) were happy and they were living and succeeding, and this park was created, and the properties were taken. There’s some resentment to that. I think I would probably feel a similar way if that would have happened to my family — and it is difficult.”

Arriving as a visitor

Helping hear those voices and understand the background is important in Lott’s work. It’s also a challenge, given the size and scope of the park. As he puts it, “In two-and-a-half hours, I can either go to the other end of the park, or I can go to Springfield.”

“It's this long, narrow thread that lays across this landscape. Instead of having one or two gateway communities, we have 15 gateway communities,” he says of the park. “Me being in the Van Buren community really allows me that opportunity because I’m living here, but I don’t have that opportunity in Salem and Eminence and other places because I’m not eating lunch, I’m not buying my groceries there, I’m not going to church there. I’m not doing all of those things that really invest me into a community.

“It’s a real challenge, and I can see that today in the relationships that I have in the southern part of the park compared to the ones I have in the northern part. I don’t have as good of a personal connection due to distance.”

Three years ago, before Lott began working to create connections, he spent time alone: in the park, as a visitor, seeing it through similar eyes as visitors have done for generations.

“I didn’t have family with me, and didn't know anybody,” he says of those early days. “Every weekend, I took my park map, and had the park history. I hiked every trail in the park, I drove every road in the park, I went to every location, and I just started to learn the park.”

Lott was still learning the park when a new experience — for him, and for the world — unfolded with the COVID-19 pandemic, which began to escalate across the country just weeks after he arrived in the Ozarks.

Part of that effort tied to disease prevention, which led to altered services and amenities in the early part of 2020. But soon, it pivoted to the reverse: higher use, fueled by folks who headed outdoors to escape the pandemic’s constraints on gatherings.

Part of that increase is anecdotal. According to park officials, 1.2 million visitors headed to ONSR in 2019 and more than 1.3 million in 2020. However, given the open nature of ONSR, there aren’t black-and-white ways to tell for sure how many people are on the river.

In the past, outfitters helped provide figures for the number of rentals they made, but given the number of people who are simply buying and bringing their own equipment today, that data isn’t as reliable as it once was. There are also factors that affect perceived usage, such as the number of motorized boats.

“In the last three years, the number of motorized boats has probably tripled,” says Lott.

Also, don’t forget kayaks. (Which apparently no one can do these days.)

“What we just did is we roughly doubled the number of vessels on the river without doubling the number of people,” he said, comparing kayaks with canoes, the latter which generally carry two floaters as opposed to just one. “But we have more people, too. On the very popular stretches of river, on a weekend, you can see a lot of people.”

A snapshot of that reality is found in Eminence, the county seat of Shannon County, where river outfitters, motels and stops for ice cream, summertime treats and pie line the town’s main drag. Along the way, visitors are greeted by a longtime sign on the courthouse lawn: “Stay a day or a lifetime in Shannon County.”

An ongoing challenge of being beloved

Those rising numbers lead to more challenges, albeit good ones: especially with increased use, how does one simultaneously provide the experience all users are expecting while protecting the land — and when change makes those old scars throb?

An example came in 2022, when ONSR released its Ozark Roads and Trails Management Plan. Adjustments brought strong response: the feelings manifested at a meeting of the Dent County Historical Society in Salem, where Lott had agreed months before to speak on another topic related to the riverways. A packed crowd redirected the conversation to an issue regarding a change brought by the plan.

Part of the reality ties to the age of the park. Given that it’s relatively young — especially compared with Lott’s previous parks, which were set aside in the early 20th century — there are plans that are still being developed. An example: prior to the plan’s release, and even though it was against NPS policy, horseback riders were allowed widespread access. Now that there is a plan in place, it feels like there are limitations.

“We look for the best solutions as we can,” says Lott. “We try to address the problems but inevitably — and we talk a lot about it — there’s no good answers on how you do it. We pick a path, knowing that there is a flawed component to it, but we do the best we can. And we apply it, and we try to be consistent with it.”

There is also the reality of visitors understanding the different restrictions and rules — not just for ONSR, which is one of several on a list of environmental agencies managing publicly owned property in the vicinity.

“There are those, a subset, that feel like public lands can be used any way you want to,” says Lott of ONSR. “That’s not the case. The National Park Service and these federal lands are held to the highest standards of preservation, protection, and you don’t get to drive wherever you want to go. It isn’t unfettered access to take and use and take advantage of this landscape.”

Looking ahead

In addition to those ongoing efforts, Lott looks to the future and improvements he’d like to see within ONSR. It’s a place where innovative thinking is paramount, especially since budget cuts have reduced the park’s full-time staff by approximately 30% over the past 20 years. Right now, a team of around 77 permanent employees and 50 seasonal staff, the latter of who serve less than six months per year, manage the park’s operations.

“That's where creativity comes in,” he says. “Is there a different way of doing business? Is there a different way to prioritize your work? So that's the challenge that the management team has taken on today. We are trying to come up with a new way of doing business here.”

One near the top of his list is enhancing the appearance of ONSR. An example: increased signage and parking options that are easy for visitors to use.

Cultural preservation, he says, is also important. An effort is at Big Spring, where restoration of the park’s dining lodge, cabins, and former museum building is underway. The structures date to the 1930s after the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) established a camp at Big Spring State Park.

Other future priorities, Lott says, include the Susie Nichols cabin, Klepzig Mill, Pulltite cabin and Howell-Maggard cabin. The Ozark Riverways Foundation, founded in 2020 and the official friends group of ONSR, is also helping raise money to restore the aforementioned Mt. Zion Church, a native stone building located at Akers.

“I hate to point out where we failed, but our historic structures and that cultural component — we need to make that a priority, and we need to focus on it,” says Lott. “We're building teams to bring in and get these buildings back into good condition. Then developing waysides and information at each one of them; creating trails and the ability to access these places. Because that's one of our charges — it isn’t just about floating a river. It's also about preserving the Ozark culture. We need to do a better job there. That's a focus point.”

That conversation extends beyond the white settlement of the Ozarks: it also involves engagement with Native American tribes.

“They’re very invested in what we do here, because this was their home; their ancestors are still here,” says Lott. “We have a responsibility to them, and it's a government-to-government relationship with them, because they are their own nations. So there's very specific ways of doing business with our tribal partners. We have some obligations that are very important with them. They have treaties that we have to honor.”

There are “dark” events to anticipate, including April 8, 2024, when Big Spring will be on the centerline for a total solar eclipse. According to NASA, “a total solar eclipse happens when the Moon passes between the Sun and Earth, completely blocking the face of the Sun. The sky will darken as if it were dawn or dusk.” Visitors may also see the darkness in a new way as the park eventually plans to apply as an International Dark Sky Park.

Lott and his staff are looking into the creation of a youth corps that can be a win-win for both the park and participants. ONSR receives supplemental labor, while students have the chance to learn a skill and get work experience and a stipend for furthering their education.

“Each one will get $1,500 that they'll be able to put towards college or trade school,” says Lott. “And if they work so many hours they get to apply for our jobs. They get to come in and be able to compete for jobs that they wouldn't have before. Then I get to watch you, and if you really are an outstanding performer, I just found a new way to bring in some good local talent into our work pool here.”

Other ideas to come include VIP villages, which Lott says are in the design phase this year. The concept focuses on recruiting individuals of retirement age — and who have RVs — to come stay at the park. In exchange for some hours of labor, they receive free utilities and the use of a clubhouse where they build a community.

“I put five RV sites around that house. That house, I turn into a clubhouse. I put the pool table in there, a TV room, little small library, shower, washer and dryer, then those five RVs around it. They come in, they commit to four months of work. I pay their bills for them. They give me 32 hours a week,” says Lott. “Now, suddenly, where I have my skilled labor out there cutting grass every weekend, they cut my grass. They do that work, and then I take the skilled labor that I have, and put them towards historic structures, or something else. Because, frankly, it takes all of us cutting grass to cut all the grass here. I've got my electrician cutting grass — but I need an electrician, too.”

While a version of the youth program will begin in 2023 through AmeriCorps, Lott says if it’s successful, he hopes to expand to a more local workforce.

“Internally, I've got to sell it there, too,” Lott says of the program. “It's easy for me to talk about it, because at the end of the day, I'm staying right in this office. They're the ones that are going to have to go out there and engage these young people and work with them and get them to do this work. Can we pull it off? We're going to find out this summer. If I can prove it, we'll do it. Then over time, I will try to expand it.”

All of those factors — from meeting people where they are, to protecting the environment and history to developing and implementing improvements to make the park better — all form why Lott invests effort in what he does.

“Personally, I like the idea — not saying that I’m necessarily successful — that you can come in and make a difference. That’s what I want to do. Can I make the place better? Do I have the opportunity to influence; to make this something that I can be proud of? My kids can be proud of me for doing? I actually made a difference and made it better?

“That’s what I want to do. When I go home at night, that’s how I judge myself: Did I make the place better or not?”

Click here to learn more about Ozark National Scenic Riverways.