This story is published in partnership with Ozarks Alive, a cultural preservation project led by Kaitlyn McConnell.

IN-DEPTH |

PIERCE CITY - Into the inky blackness the train whistle screamed, its shrill call reminding those who heard it both where they were and that they were alive.

“There,” in this case, was in the heart of Pierce City, a town just west of Monett, where a group gathered on August 19 — fire in hand and a common mission in mind. The focus of those gatherings, however, drastically differed depending on which August 19 they stood along the town’s main drag.

Because gatherings have happened on that date more than once.

In 1901, an angry mob launched a night of terror that resulted in three men dead, the town’s Black community banished, and, for some, the start of a chapter of collective community amnesia.

But history long buried has a way of coming back to life. And more than a century later, it was a different group who gathered in the same place at the same time on the same night, just a stone’s throw from the former Black community. Instead of torches once used to destroy Black residents’ homes, the handful of people held candles in memory of the history that happened.

“This is where the lynching itself took place,” said Murray Bishoff to a group of around 20 people who came to hear him speak about the history of the moment that changed Pierce City forever. “So that’s why we come here, and we come here at this hour because, according to one of the accounts, the evening kicked off with the arrival of the 9 ‘o clock train from Monett.”

Three decades researching and sharing the story

Bishoff, a 68-year-old retired newspaperman who lives in Pierce City, has spent more than three decades researching and sharing the story of the fateful, hateful night that feels so far away.

In 1991, he wrote a three-part series chronicling the lynching. The series, which appeared in The Monett Times, began a new conversation about the event, which was seemingly largely ignored after it happened.

In the years since, Bishoff has worked to raise awareness about the tragedy in a variety of ways, including at the annual vigil where he stood once again in 2022.

“It seemed to me that I had been dropped out of the sky into this place to do this thing,” Bishoff says. “I was an agent of change, and I had to embrace my fate essentially. I felt compelled that I was the one that needed to do it, and consequently, here I am, the curator of this story.”

It all began years ago with finding an old news clipping about the lynching at the library. A longtime local had recently gone into a nursing home, and the piece of newsprint somehow made its way to the library — and into Bishoff’s hands.

“I came across it one Saturday afternoon, and I read that, and it was ‘Oh my God,’” he recounts.

That piece of newsprint didn’t tell him the whole story, but it set him on a mission to learn more about the moment that still stands in infamy.

STORY CONTINUES BELOW

The night that changed everything

As with many events in history, the lynching did not occur in a vacuum. Years of history contributed to a time and place that required only a match to erupt and ultimately manifested in a night that changed everything.

Pierce City — also spelled Peirce City in its early years — was incorporated in 1870 and had a population of several hundred Black residents by the turn of the 20th century. The number had increased after the end of the Civil War, when word was sent to Kentucky that the town was a good place to be, Bishoff says.

Black people came and established a presence in the growing town. By the late 1800s, it was a bustling place of around 3,500 residents, Bishoff says, with a college, schools and churches. It wasn’t a utopia, and issues did exist — but compared to some other places, it appears that Black and white residents co-existed relatively peacefully for years.

That all changed on Aug. 18, 1901, when a trip to church ended with a Pierce City woman dead.

Her name was Gisela Wild. The 23-year-old was found along railroad tracks, her throat slashed when walking home from church. Her brother, Carl, found her as he also began walking home a few minutes later.

Word quickly spread. A bell rang the alarm as the hunt for a killer began. Things grew even more heated when individuals reported that they saw a Black man in the vicinity around the time of the murder.

Sunday turned to Monday

By the next day, two Black men — Will Godley and Gene Barrett — were taken into custody, even though there was little evidence linking them to the crime. For Godley, the biggest incriminating factor was history.

Years prior, Godley had spent time in prison for allegedly assaulting a local white woman. Despite weak evidence, he had been convicted of the crime and spent several years in jail, leading to a belief that he had committed this murder as well.

As the sun set, a restless crowd, a day of gun sales — which weren’t made to Black people — and the arrests of Godley and Barrett created a tinder box.

“The news was quickly brought to town and spread over this and the adjoining counties,” noted the Springfield Republican. “The town and surrounding country was soon alive with hundreds of determined men, who were thoroughly armed. Bloodhounds were secured from nearby towns and quickly took the scent. They traced Godley down, and he was taken charge of by the officers and placed in jail in this city. One other suspected negro was also arrested.”

“All Sunday afternoon and all day today (Monday) the crowds poured into the city from the surrounding country, and while all did not join the mob, they have been collected in crowds and all the corners in the business portion of the city all day.”

Despite those factors, Pierce City Mayor Washington Cloud declined offers from the National Guard to help keep peace. He thought locals could keep things under control.

That did not turn out to be the case.

The restless crowd continued to grow, aided by people from other communities arriving by train. By the 9 p.m. stop, a mob of around 1,000 people had gathered in Pierce City, hell-bent on so-called justice.

They eventually went to the jail, claimed the two prisoners, and marched them down the street. One of the prisoners claimed he knew who did it; they took him away to jail in another town to be questioned further. But Godley, perhaps shaded by his previous and possibly unjust dealings with the law, refused to talk.

He was led up the stairs of a hotel and hanged. It was the second attempt, as the crowd initially tried to use a telephone pole, but the rope was too short.

But when Godley was pushed off the balcony of the Lawrence Hotel, not only was he hanged, but his body was soon riddled with bullets, and the crowd’s yell was great.

“The mob was composed of the representative farmers of this vicinity, and many well-known citizens of Peirce City were among its number,” reported the Republican. “None wore masks, and it is known who many of them were, but the people would rise up in a mass against any investigation which tended toward the punishment of the leaders or any member. Everyone concurs in the steps taken, and there was not a man on the streets tonight who would say the negro should not have been hung.”

The mob was armed with more than the guns they bought and brought: They broke into the National Guard armory, taking 50 rifles and ammunition.

The riot, however, was only the beginning of the evening from hell. The mob next headed for the Black community.

They initially sought Pete Hampton, who folks side-eyed as a possible suspect in a shooting two years prior. Upon reaching the Black community, an account says the mob was fired upon by those who lived there. That action prompted a group of around 150 people to circle back, ultimately torching numerous homes and shooting into the community.

“The crack of the Springfield rifles which the mob had taken from the armory was incessant,” recounted Lieutenant W.C. Gillen of Company E. “I could distinguish their sounds from that of the shotguns, rifles and revolvers carried by the other men. Pistols and all sorts of small firearms were pumping lead into the burning buildings.

“Old soldiers said it looked like an attack on a fort at night. The members of the mob were yelling and hooting. The negro women and children were crying and screaming. And over all the flames shot up, and the lurid smoke ascended to the clouds.”

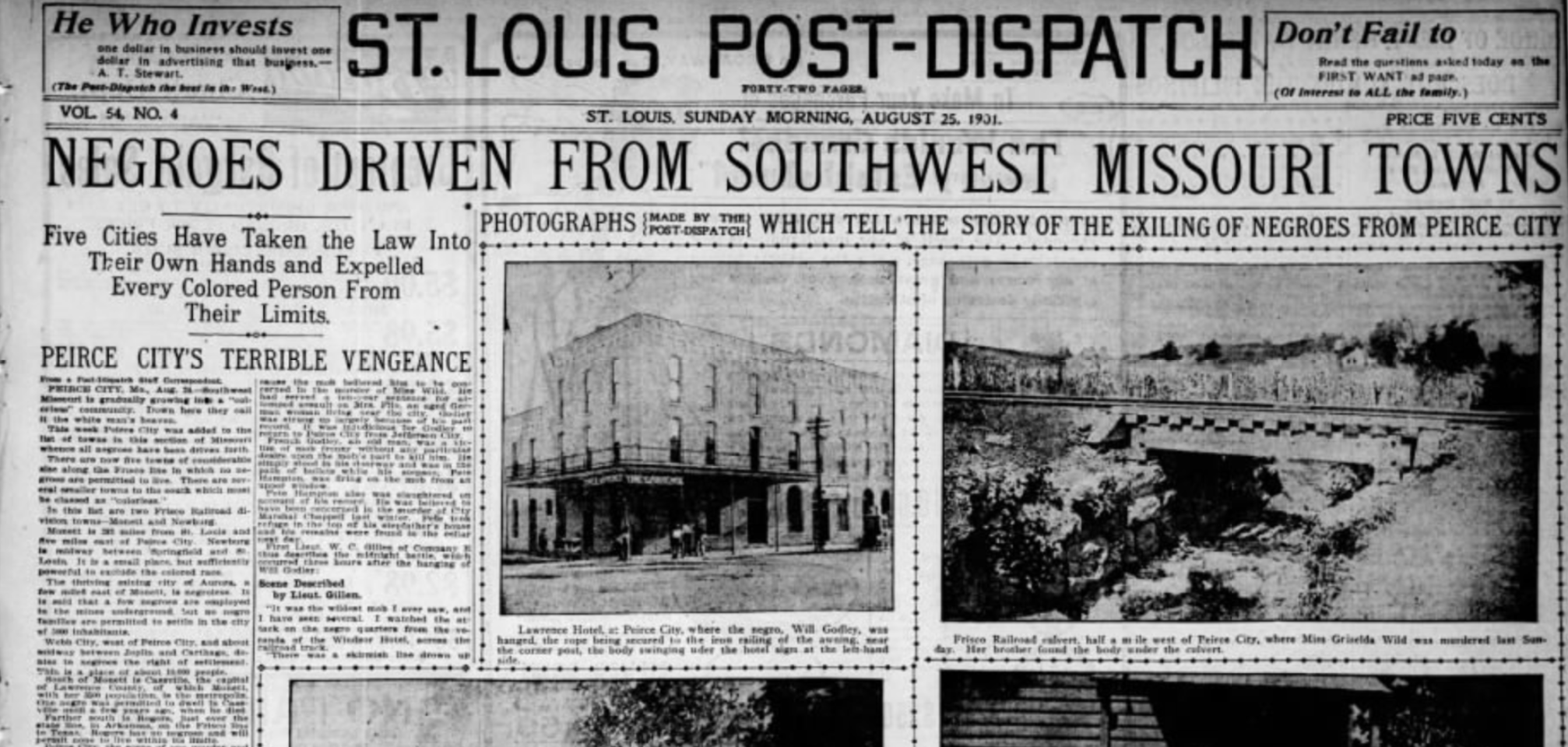

Gillen’s memories were only one vignette of several recounted about the mob scene in a front-page story in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch a few days after the lynching.

“When the mob attacked the houses and began firing, we all dropped first on the floor to keep from being hit,” said Rev. S.S. Pitcher of Carthage, who was in town to lead a revival, through the paper. “A volley came crashing in over our heads. After a while, there was a lull in the firing, and we all crawled to the cellar. I should say that 200 shots were fired into (the) house before we got out.

“We walked eight miles to Berwick, then two miles and a half to Jolly, then fifteen miles to Sarcoxie — more than 25 miles in all. There we took a train for Carthage, arriving Tuesday night.

“I am utterly worn out with a night and a day of walking amid hostile white people. The whole country between Sarcoxie and Peirce City seemed to be aroused. My church tent is still up at Peirce City, and I don’t know when I can get it.”

Before things were said and done, three Black men were dead and members of the Black community had run for their lives. Some came back the next day, but they were told to leave and never return.

“A great many boarded trains in town. By the end of the day, the entire Negro population, including those who lived just outside the city limits, had departed,” Bishoff wrote. “Tension in the community seemed to abate then. Gisela Wild’s funeral on Tuesday reportedly drew more than 1,000 people. Will Godley, French Godley and Pete Hampton, the three Negroes killed by the mob, were buried nearby in the unmarked potter’s field, with no mourners present.”

Even mere days after the lynching and racial cleansing took place, there were already doubts about the guilt of the men killed. One note appeared in a San Fransisco paper, which was initially published in Springfield.

“It is now believed that Will Godley, who was lynched, was not the real culprit,” noted The San Francisco Call. “Citizens say that negroes will not be permitted to live here in the future and that the few negroes not already expelled will be obligated to go.”

Misplaced guilt, however, did not change attitudes about the presence of Black residents. They had to leave. No exceptions.

“That’s the South, too,” said Mrs. Cobb, who moved to Pierce City from Kentucky, through the Post-Dispatch, “but give me the South in preference to Peirce City. They are supposed to hate colored people down South, but I was never treated like this. Kentucky is good enough for me, and I want no more of Peirce City, though I want to save my property there if possible. We have all worked hard to buy our little home from Banker Allen, and if there is any law and justice in Missouri, I don’t see how they can beat us out of it.”

Newspapers beyond the Ozarks covered the lynching, including in Kansas, Oklahoma, Nebraska and Iowa. It was condemned by Booker T. Washington, a former slave who ultimately founded Tuskegee University and became a U.S. presidential advisor, without words.

“Booker T. Washington … would not talk about the affair,” the Fort Scott Daily Tribune noted. “He said it would be too difficult to express himself so that he would not be misunderstood.”

Tone varied on how papers presented the issue. A local mention of note is in a strong editorial in the Republican; while its main impetus was to snark back at the rival Springfield Leader-Democrat about its coverage, the paper also strongly opposed the event in Pierce City:

“This work at Peirce City is a monumental crime and it demands redress at the hands of an outraged people.

“The governor of Missouri should see to it that those who have been driven out of their homes be sent back and protected in them, and that as far as possible these wrongs should be redressed.

“The press and pulpit should come down on this case of wanton murder with one voice. It is a case without a redeeming virtue and there are no politics about it. The mob has taken the lives of three innocent men and so mismanaged matters as to help the guilty man to escape. When we publish these plain facts and and comment on them, the L-D tells us that we are making a matter of politics of it. The L-D is very seriously mistaken.”

Initial aftermath

While the most horrific, Aug. 18 and 19 were not the only days implicated in the lynching chronology, nor did it contain the only deaths. There are at least five people dead as dawn broke on Aug. 20: Wild, the three lynching-related victims, and a boy accidentally shot as the mob fired at Godley.

Another was added a few months later when Rev. Smith, a man who traveled many miles by road and river to get away from Pierce City, passed away as a result of the experience.

“It is charged by his friends that the colored minister’s death is directly traceable to the Peirce City affair a few months ago, which cost the lives of several of his race,” noted the Greenfield Vedette in December 1901. “The life of any negro, good, bad or indifferent, was forfeited had he been found in Peirce City that night, and the preacher, with members of his flock, took refuge in flight.

“Later quick consumption developed from the exposure experienced on the race for life, ending in his death in Lamar as above stated.”

Like the leadup to the lynching, other results rippled from the event. Two other suspects — Joe Lark and Will Favors — stood trial and both were acquitted. There were other days in court, including when two former Pierce City residents filed civil suits against around 20 Pierce City men. Eventually, that number was reduced to four defendants.

“Not only will the suits be sensational should they come to trial, but the mere news of the filing brings back unpleasant memories and recalls a crime the people of the city would willingly forget,” noted the St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat in August 1902.

It appears there were four people involved in the lawsuits: America Godley, Will Godley’s widow; Beedie Hampton, Pete Hampton’s widow; Sarah Godley, the mother of Pete Hampton and Will Godley, and wife of French Godley; and a man named Charles “Doc” Brinson, who sued for damages to property and punitive damages.

The lawsuit filed by Sarah Godley went to trial in February 1903.

“Because Sarah Godley lost the most — husband, home and two sons — her case went forward first by the attorneys from Webb City and Carthage who represented all three Negroes. Her two-day trial came up on Feb. 18, 1903, in Joplin. A large group of witnesses, both Whites and Blacks from Pierce City and Black former residents, were in town for the dramatic showdown,” Bishoff wrote in the series’ third installment.

Sarah Godley was not awarded any damages. Instead, attorneys argued that convicting the defendants would mean they were guilty of murder and open them to further prosecution. One of the attorneys also argued that since French Godley was elderly, his widow was better off without him.

America Godley’s suit didn’t get a verdict; on the day of the trial, she simply didn’t show up. It was determined Beedie Hampton “didn’t qualify,” so her suit didn’t move forward. And it’s unclear what happened to Brinson’s efforts.

Brinson’s claim speaks to another point that affected former residents: Since Black former residents couldn’t return without risk of death, the property they owned was seemingly lost to them. Today, a large grassy area in Pierce City remains where their houses stood.

Pierce City was added to a growing list of Ozarks “white only” communities, which by the early 1900s included Joplin, Webb City, Aurora, Monett, Harrison, Ark., and, to an extent, Springfield.

And the small Lawrence County community has remained as such to this day. According to 2020 U.S. Census data, of Pierce City’s 1,251 residents, 1,094 were White.

Just five were Black.

Remembering the story

While hundreds of Black individuals would never forget the things that happened in Pierce City, for white residents, it seemed the preferred course of action was to simply move on with life.

It appears that largely happened — until around 90 years after the lynching, when Bishoff stumbled across that news clipping in the library.

Bishoff hadn’t been in Pierce City long before he made the discovery. A native of Pennsylvania, he moved to Pierce City in the late 1980s with his first wife, whose family lived in the area. He had a background in the comics industry and eventually was hired at the Monett Times as news editor.

That role, a deep love of history and the new-to-him knowledge sent him into hyperdrive.

“I let it sit for a while. I finally decided I needed to know more,” he says. “I started going to the newspaper records, and I found they didn't match. So then it was like, ‘Well, I'll have to go through everything.’

“So I started gathering every frickin’ record that could possibly exist. I got into the courthouse. I went through the assorted records that were in the old vault up in the circuit clerk's office. In the pile of papers for Joe Lark’s trial were the 65 typed pages of interviews from the coroner's jury — just tucked in there. Nobody had ever opened that packet of stuff. And I photocopied them all. Those are now up in the attic of the courthouse.”

He also began searching through newspaper records, starting prior to the lynching, to help paint a picture of where dynamics stood in the town.

“I went under the premise that Pierce City was a hostile town. This is a consequence of what you would get if you had a hostile environment,” Bishoff says, but he was mistaken. “Newspapers didn't show that. Newspapers showed a somewhat combative but a town friendly towards everybody. So it's like, ‘What? Something just doesn't add up here.’

“One day, I'm at the office while I'm working on all of this, and I mentioned this to Wilma and she says, ‘Why don't you write it up?’”

Wilma Henbest, the then-managing editor of the Times, had an unusual career for a woman in her day and age. Henbest was from Monett and began working at the Times while she was in high school, initially serving as a part-time reporter and proofreader. She went through several other roles before assuming the position of managing editor in 1975. In total, she worked at the paper for around 40 years.

Despite her longtime connection with the community and — her birth just 28 years after the lynching — she didn’t know much about the incidents.

“She had known something,” says Bishoff of his former boss, “but she didn't have the background.”

The newspaperwoman died in 2006, so one can only hypothesize as to her thoughts about the decision to print the stories. But whatever reason or rationale, the stories were set into type and printed on the press.

“Publisher Stephen Crass was so uncomfortable that he ran the whole series past the corporate attorney, who said if it's history, it's safer,” says Bishoff.

The first in the three-part series debuted on Aug. 14, 1991 under the headline “The Lynching That Changed Southwest Missouri.” It appeared on the front page along with news about Ernte-Fest, an annual German festival in nearby Freistatt, the closing of the Monett Municipal pool for the season, and Purdy’s purchase of a police car.

“In the history of every town there are crucial events that shape the course of things to come,” the first installment began. “For Monett, the movement of the Frisco railroad from Pierce City in 1887 changed the development of both communities.

“The establishment of the Monett Chamber of Commerce’s Industrial Sites Fund in 1946, what would later become the Monett Industrial Development Corporation, likewise opened an avenue for growth of a small complex for the city future, which stepped in as the railroad declined.

“There are other events, of a darker nature, that affect people in a very personal way.

“This Sunday and Monday mark the 90th anniversary of one of the most terrible events in the history of Pierce City, which ultimately has affected race relations in southwest Missouri to this day.”

The three papers — which “sold out like nothing anybody had seen before,” Bishoff says — focused on different aspects of the lynching and aftermath. The first shared Wild’s murder, the hunt for the killer and the lynching itself. The second was about the murder trial. And the final installment told of Black former residents’ efforts to sue Pierce City, which concluded with a closing comment:

“This series of articles has not been meant as criticism of the community. It is the sincere belief of the historian that knowledge of the past only provides a better understanding of the present, and a guide to the future.”

Bishoff says feedback to the articles was mixed. There were people who felt the story didn’t need to be told; that sleeping dogs should lie.

“I had another older fellow who called me and said, ‘We’d just gotten over this. Our town’s just coming back, and now you’re bringing it all up again.”

An unexpected moment was the voice of Harry Rutherford, who stopped by the newspaper office the day the final installment was being printed. More than 100 years old in 1991, Rutherford came forward to share his own recollections of the lynching period, which he assumed was the only firsthand account still available at the time.

He wasn’t in town the day of the lynching, but the day after, he heard about it from a Pierce City man who came to their property to dig a well. He arrived later than expected, he said, because he got “caught up in the excitement” of the night before.

The paper after the final installment — on Aug. 19, 1991, the exact anniversary of the lynching a near-century before — included a front-page announcement: Henbest would retire from the Times after 40 years of service, and Bishoff would take her place.

It’s a role he held for nearly 30 years until his own retirement in 2020. He hasn’t quit writing, though: Just days ago, he launched a website called “Murray Press.” It’s where some of his biggest stories live, through which he plans to publish others in the future, and how he sells novels he’s written.

Seeing change

Bishoff’s documentation in the Times was only the start of his efforts to preserve the history of the lynching for the future.

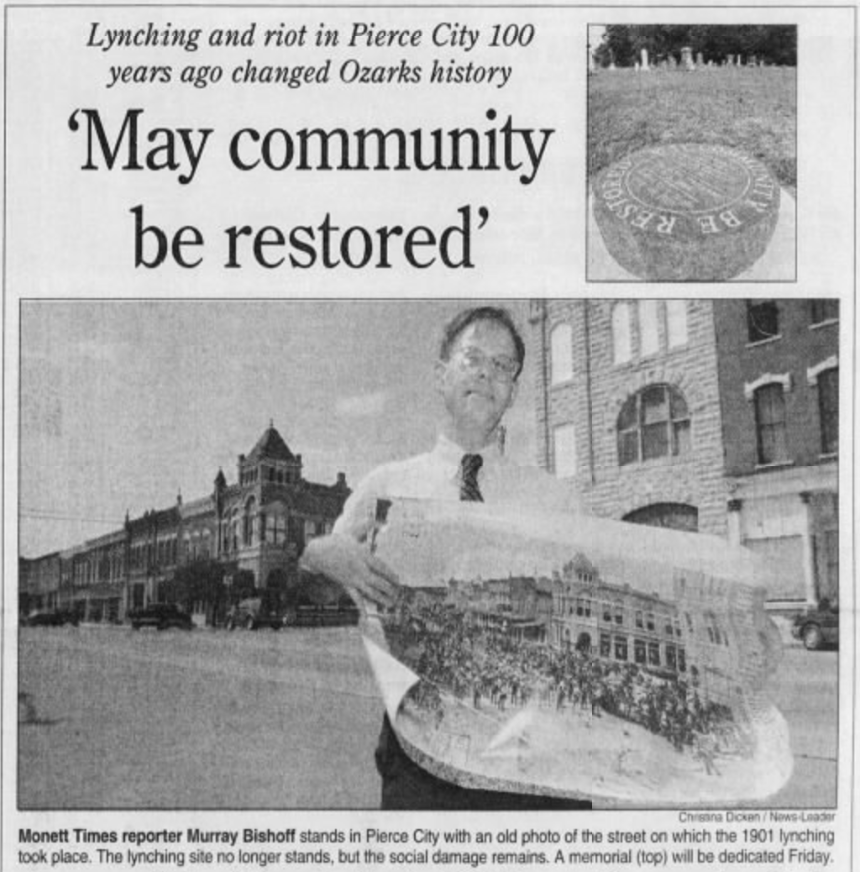

Ten years after the story series ran — and on the 100th anniversary of the lynching — a monument was installed in the Pierce City Cemetery to honor the victims. Bishoff paid for most of it himself.

“All of this … is an effort to come to grips with what happened,” Bishoff told a Springfield News-Leader reporter in 2001 upon the marker’s dedication. “You can’t come to grips with this story by forgetting about it.”

He also spent years writing a novel about the lynching. It has yet to be printed.

“They would need it fleshed out,” he says of why he went the direction of a novel. “I felt that there were so many angles that the only way I could get at it was to try the historical novel approach. It was such a deep dive — I spent five years writing it.”

Others beyond Lawrence County have taken notice of the lynching. In 2010, “White Man’s Heaven” a book focused on lynchings and expulsions of Black people in the southern Ozarks, focused on events in four communities, including Pierce City.

Documentarians, too, have come to town: Just one example is “Banished,” a production that focused on three towns where Black residents were expelled in the early 1900s. Two of the communities — Harrison, Ark., and Pierce City — are in the Ozarks.

The documentary was produced in 2006, was shown on PBS, and also included a visit to the local senior center. At that time, few people showcased in the film were familiar with the facts of the lynching.

Around Pierce City, Bishoff has made it a mission to share the story. He has spoken to school groups and has served as a point of contact for people who reach out to Pierce City seeking information about the lynching.

He’s filled in gaps for folks who grew up not knowing, like Janell Patton, who is from Pierce City and whose family goes back generations in the town.

“I first heard about it from Murray several years ago,” she says. “I didn’t know about it until he started to shed light on what happened. It haunts me that this happened in the town I grew up in.”

Bishoff’s work has also helped provide historical context to people like Kyle Troutman, the editor of the Times and the Cassville Democrat. Bishoff also shared the story with him when he relocated for the job in 2014.

In the years since, Troutman says he feels remnants of racism still exist in the area.

“It’s something that, given the history of the area and things that continue to happen that oftentimes go unreported, it’s still an issue,” Troutman says. “So I think, speaking to that, how important it is to take a stand and keep it going because there’s still such a prevalence of it. It’s not as in your face and obvious as it used to be, but it’s still there.”

Troutman gives an example that happened shortly after he arrived on the job. A Black man who was a member of the local fire department was tased by a gas station employee after the employee was allowed to play with a police officer’s Taser.

“When I first got here, there was a guy that I did multiple interviews with. He was on the fire department. He got tased by a Casey's employee when the officer let the Casey's employee play with his Taser. So he got tased, and … there was a lot of racially motivated stuff. There was a lot of stuff going on, and he was coming forward with it.”

The story ultimately wasn’t published because the Black man moved away.

“About two days before we were going to press, he was like, ‘I’m leaving. I don’t want to do the story.’”

In an area that is still overwhelmingly white, what is the true picture of race, or racism’s role in a community?

While one person couldn’t definitively answer that question, I hoped thoughts from Pierce City’s mayor might add some food for thought. Unfortunately, after reaching out to city hall, I learned Pierce City is currently without a mayor, and no one else was suggested as a spokesperson on the city’s behalf.

Looking forward

It’s been 31 years since Bishoff’s initial reporting on the lynching was published in the Times. The people who were one generation removed from the actual event when the original stories were printed have faded into the past. Many of them are found on the rolling hillsides holding the Pierce City Cemetery and adjacent graveyards for St. Mary’s and St. Patrick’s parishes.

Walking through the cemetery, Bishoff points out other people who were personally involved that night.

“There’s quite a few people in the story right here,” he says.

He continues walking through the cemetery to a relatively open patch of grass.

“And this is the marker,” he says, coming to stop near a round stone.

The stone bears the names of the victims, dates of their births, and the words “may community be restored.” It was strategically placed near the graves of Will Godley’s mother and grandmother.

“It’s made of black granite, which is the hardest stone that you can get, so that if somebody dumped paint on it, you could actually get it off,” says Bishoff.

That, however, hasn’t been necessary. “It’s never been disturbed,” he says. “No one has ever bothered it.”

Bishoff paid for most of it himself, although a handful of donations help offset the expense, and the monument company gave it at cost.

“I continue to run into people who stumble across this and wonder if that’s what it looks like,” he says. “And indeed — when it says, ‘Killed by a mob,’ that’s what it’s there for.”

It’s only a few feet away from many of the town’s white residents, and also from the other victim in the crime: Gisela Wild, the woman at the heart of the story, even though she doesn’t realize it.

A small bouquet of flowers lies on her tombstone.

Bishoff placed them there as he always does on Aug. 18, the anniversary of her death.

The next day, he holds an annual candlelight vigil in memory of the tragedies that took place, at the same spot where so many gathered on the same date so many years before.

It doesn’t look like the same place it did back then. A tornado in 2003 destroyed much of the downtown district, leaving basically only one row of old-time storefronts. It was from those buildings that people could have seen the lynching and devastation. Today, they remind of a different time in the open air, where vehicles drive by with regularity, even in evening hours.

“Every year when I do that ceremony, we’re so exposed out there I still worry about somebody coming along and shooting me,” he says.

Does that kind of animosity still exist, I ask?

“It only takes one knothead,” he says.

Up the hill, though, another remnant reminds: The former town hall, built in the late 1800s, with the same bell that once rang to sound the alarm after Wild’s murder.

The annual vigils have been taking place since the mid-1990s, but were originally very small in size. Things began to grow during the centennial in 2001, and this year, around 20 people gathered with lawn chairs to hear Bishoff speak.

Two of those people were Preston and Katie Reynolds, a husband and wife who traveled around 40 minutes from their home in Webb City. They attended in both 2021 and 2022, and plan to make it an annual tradition.

“I was just shocked,” says Katie Reynolds of hearing the history for the first time. Even though she also grew up in the Pierce City area, her first vigil — which the couple attended after learning about it on Facebook — was her real introduction to the story.

“I was pretty surprised that it wasn't talked about, and we didn't know. I was disappointed in myself I guess, just for not knowing. We didn't hear about it in school.”

Looking at her own lifetime, she sees shades of racism that at times cover lynchings and racial violence. Things, she says, people wanted to leave in the past.

“It was definitely a ‘90s mentality of ‘That was then; now, it doesn't exist anymore,’” she says. “But as I got older, I think it's very prevalent here still. In the past few years, I think it's gotten – I don't know, come out of the woodwork a little bit more.”

To her, awareness of history is of great importance in helping create a different future.

“I think we can become very detached from slavery, very detached from people not having basic civil rights,” she says. “Today, (someone) could walk in Pierce City and literally walk on the spot that someone’s life was taken due to a lynching, and they just not know it.

“We have to learn about it.”

As Bishoff told the story at the vigil, attendees held candles — instead of torches — and remembered the lives. The ones killed, most definitely.

But also the ones Pierce City simply lost.

And connecting the moment and memory, the train whistle blew.

To read more of Bishoff’s work, click here to visit Murray Press, his new website.