This story is published in partnership with Ozarks Alive, a cultural preservation project led by Kaitlyn McConnell.

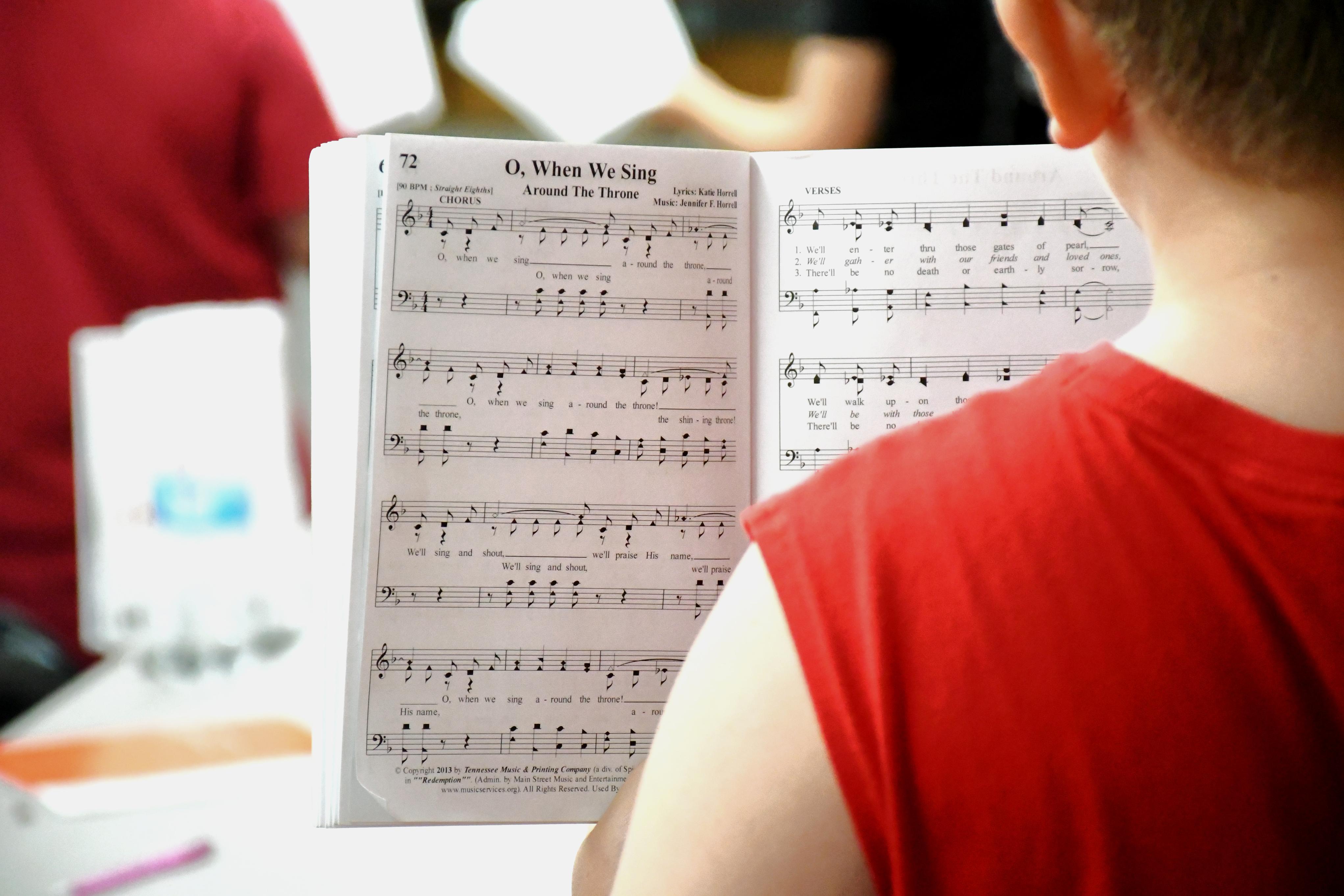

BROCKWELL, ARK. - Echoes of the past come to life through voices of the present at the Brockwell Gospel Music School, where shape-note singing sounds every summer — as it has for 75 years.

The kids and adults with songbooks in hand and voices rising to the rafters link to 1947. That year, Orgel Mason and a group of local enthusiasts first led folks to gather at the grassy creekside spot to learn the fundamentals of shape-note singing, a style of music in which note heads appear as specific shapes and correspond to syllables.

“There was a need in churches for musicians and song leaders, and they were like, ‘We can't afford to send people to Dallas,” says Beverly Meinzer, the school’s manager, referring to where instruction was offered. “It's very expensive to get there in the ‘40s and ‘50s. So they just made one here.”

Sectioned by age and skill level, participants spend two weeks of their summers learning the essentials from teachers who often have ties to the school themselves. Even with changes in the world around them, interest in the school hasn’t disappeared with time.

“We used to run about 70 or 80 (participants). And some years, I've seen it when we had 50,” says Meinzer. “But this year, we've got about 140 now, so we're excited about that.”

Looking back to the beginning

The world was different when the institution began, beginning with its name, which was simply the Brockwell Music School.

World War II was still fresh, as was the Great Depression; local farming practices were changing; and some folks were leaving the area, at least temporarily, in search of work. But the legacy that led to the school’s development actually had deeper roots than that day and time: A foundation was laid with the start of the Izard County Singing Convention, an ongoing musical gathering which began in 1910.

“The singing-school tradition goes back to the time of the Second Great Awakening on the American frontier in the first years of the nineteenth century,” notes information on Brockwell’s website about its history. “This tradition contributed significantly to the growth and power of the great revivals that especially captivated gospel-hungry settlers in the frontier South in the first third of the century. Itinerant singing ‘masters’ gave musical instruction to far-flung, often musically illiterate students. The students learned rudiments of music and the basics of Christian teaching for the purpose of their spiritual improvement.”

With little way of getting students to other places to learn, Mason found “here” to be the best location for a school. That led him, along with L. L. Floyd, Steve Jones, Jeff Cooper, and Thomas and Ethel Brockwell to officially found the endeavor.

“Like almost all the young men of his era and place, Mason came of age during the Depression, facing little more than the prospect of following in his father’s footsteps as a poor scratch farmer on the rocky hillsides and narrow creek bottoms of the Ozarks,” penned Dr. Brooks Blevins, Ozarks historian and author, for “Southern Cultures” publication in 2016. “A singing school at the rural Methodist church his family attended opened up a new world to young Mason. Eventually, he found a mentor in Luther G. Presley, a songwriter and singing school teacher who maintained an Arkansas office for one of the nation’s leading gospel songbook publishers, Texas-based Stamps-Baxter, the company that would publish ‘Heavenly Highway Hymns’ two decades later. Mason completed Stamps-Baxter’s normal school in Dallas before launching his own career as a singing school teacher in the late 1930s.”

If old newspapers are any indication, Mason largely lived a life for God and music. In addition to leadership roles in the local activities, including as president of the local singing convention, Mason spent decades as a piano tuner. As of 1979, an article in the Baxter Bulletin newspaper reported Mason had published more than 40 gospel songs. He also remained a staunch advocate and leader in the school throughout his life.

“I tell the kids that although we teach gospel songbooks, they can learn to play all kinds of music, using the same knowledge,” he said through the article about the school.

Mason died in 2002. When the former gathering space, known as the tabernacle, was replaced with the current auditorium, it was named in his memory.

A schedule, hung on the wall of the auditorium, shows how the day is divided: Class, group singing, sight-reading and ear training take place between the school’s daily hours of 9 a.m. and 3:30 p.m., as do private music lessons for those who choose to pay a little extra beyond the school’s $50 tuition. It’s a change from the early days of singing schools when instruction was paid in “home-cured hams, corn meal or live poultry,” as one newspaper article mentioned.

“We just never have turned anybody away because they don't think they can afford it,” says Meinzer. “Because if you can learn music early in life, you have that with you the rest of your life. You may not be able to play sports the rest of your life or work heavy equipment (or) machinery, but you can sing and make music your whole life. So we try to make sure no one feels like they can't come just because of the cost.”

The addition of the auditorium is only one example of the growth and change over the years for the school, which was incorporated as a non-profit organization in 1969.

Long gone is the pavilion-like structure where folks once gathered, instead replaced by buildings that have been added or converted — a former one-room school is one, an old store is another, and what was the post office is a third — for the cause. Those spaces serve unique needs, such as the breakout of different levels of classes as well as private lessons.

The session is two weeks instead of three and is held in June instead of July. They’ve adapted to needs and ideas of the times, such as by adding ukulele as one of their options for lessons, since it’s an instrument easier for younger children to hold. Those students come both from right down the road and far away, leading some to stay with friends or relatives while the school is in session.

“Since Brockwell has no hotels or motels, visiting students often stay in Melbourne, Calico Rock or in the homes of local residents,” noted the article from 1979. “Others from a wide region commute on a daily basis. The yearly enrollment averages about 100 students.”

One of the people who grew up at the school and now comes back in a new capacity — as a teacher — is Natalie Stephens, Meinzer’s daughter, who represents the fourth generation of her family’s connection with the school, as her great-grandfather was one of its initial supporters.

“I’ve been coming to the music school my whole life. I've enjoyed being a student, and now I get to teach, which is fun; just get back to something that I love as well,” says Stephens. “I've got to see a lot of different people in the roles as teachers throughout the years, which has been awesome because I've seen them loving on the school and giving back to it and showing their passion for music. Now I get to do the same.”

All classes convene for singing from 11:15 a.m. for group singing, a 45-minute window when Meinzer stands at the front of the auditorium and directs the students through songs. Groups of students, some not tall enough for their toes to touch the floor when seated on the pews, come up and help her direct from time to time, keeping time with their arms.

“Very nice job!” says Meinzer from the microphone, with notes of encouragement: “Now, we’re all just learning — some of us, it takes some time to learn a little bit of that. It’s a little bit hard to do at the first.”

Roundabout the noon hour, a prayer sets everyone on a dash to the back of the room for lunch boxes, which are taken outside and opened atop brightly colored blankets spread on the lawn. As sandwiches, chips, soda and other fare come out from boxes and bags, it feels like a simpler time, especially after food is eaten and kids get up to run and play, or explore the creek — with few phones in sight.

“We don’t really have service here unless you go stand by the road,” says Meinzer. “So we use our phone as a clock. And that’s about it.”

Those who keep it alive

On a nearby blanket, Katherine Webb Smitson sits with her great-granddaughters — representing the first and last (as of late) generation to attend the school, a reality that spans four generations and around 70 years of their family’s history.

“When I was a little girl, I started coming here,” says Smitson, who is in her late 70s. “My daughter — she went here, and my granddaughter came here. Now, these two are our great-grandkids.”

“They like the music, but they heard us talk about it so much that they liked to go ahead with the tradition.”

Those great-grandkids come and stay with Smitson to attend the school, which harkens back to her own dad taking a carload of kids to attend the school when she was growing up.

“We would practice under the shade trees. It was nice. Back then, we all dressed up — the whole time, we wore dresses,” she says of days immortalized in black and white photos on the wall of the school’s auditorium.

A similar legacy is preserved at a picnic table outside, where teenage-ish girls sit together, all with different stories of how they came to Brockwell.

“A lot of my family has come here — my parents and their parents,” says Emma Pratt, who turns 13 next week. Across the table, tuna sandwich in hand, is Eva Higgins: “It’s really, really fun — you get to see lots of friends you otherwise would not get to see.”

Closer to the creek, Joey Conway ties excitement to higher reasons.

“I would say because it’s a good opportunity to hear the gospel of Jesus and to make a lot of friends,” says Conway. “It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity you don’t want to miss.”

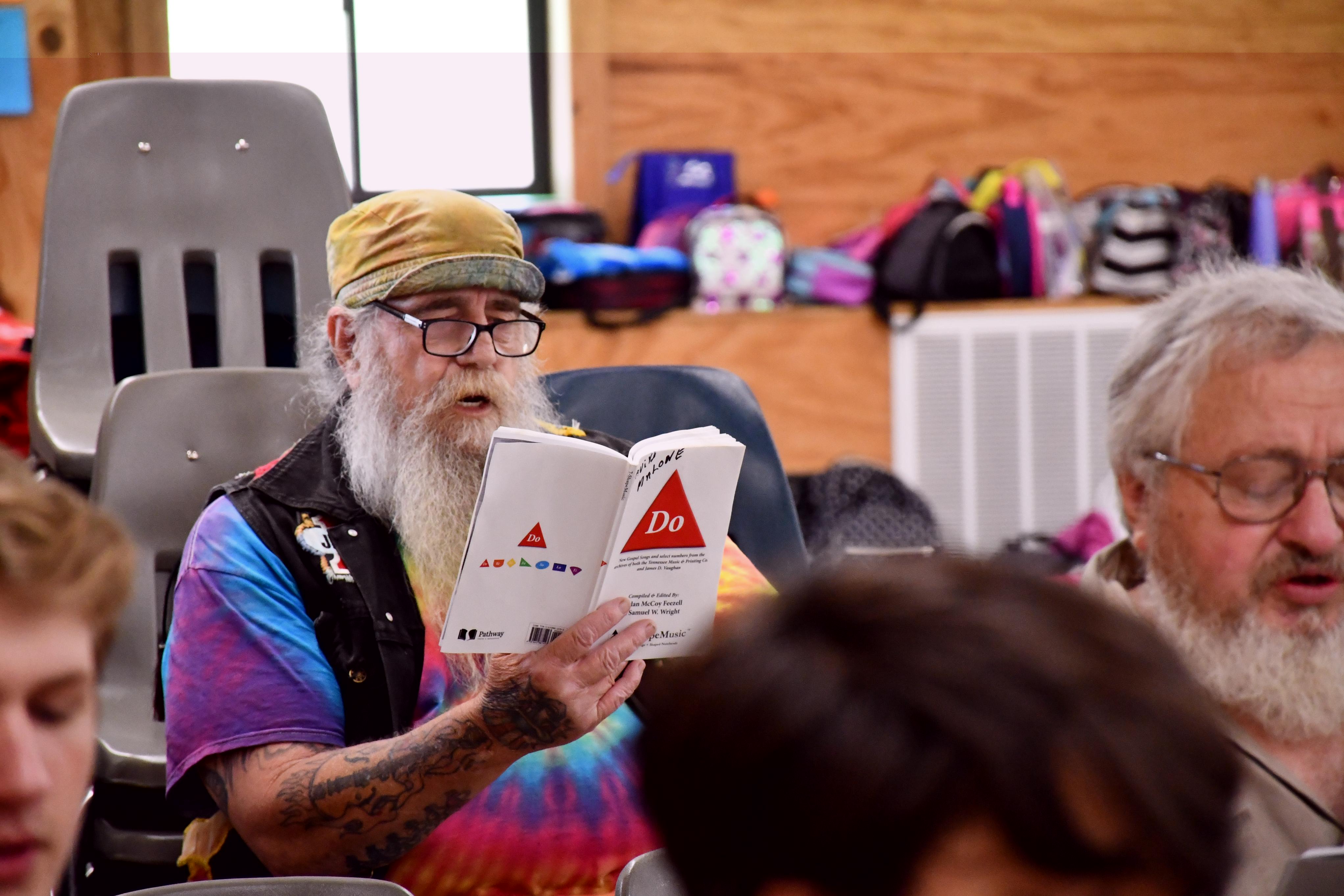

That religious call is a reason David Malone, 64 years old, decided to come back to the singing school. He attended a term years ago, but a motorcycle accident recently brought him back to religion.

“I came back here so I can learn to sing for the Lord again,” he says. “I want to get my voice back, and not be so shy.”

Kaitlyn McConnell is the founder of Ozarks Alive, a cultural preservation project through which she has documented the region’s people, places and defining features since 2015. McConnell regularly shares her stories with readers of the Hauxeda. Contact her at: kaitlyn@ozarksalive.com