This story is published in partnership with Ozarks Alive, a cultural preservation project led by Kaitlyn McConnell.

Walter Majors wasn’t here.

Technically he was — in the early years of his life, the ones we in the Ozarks generally try to claim.

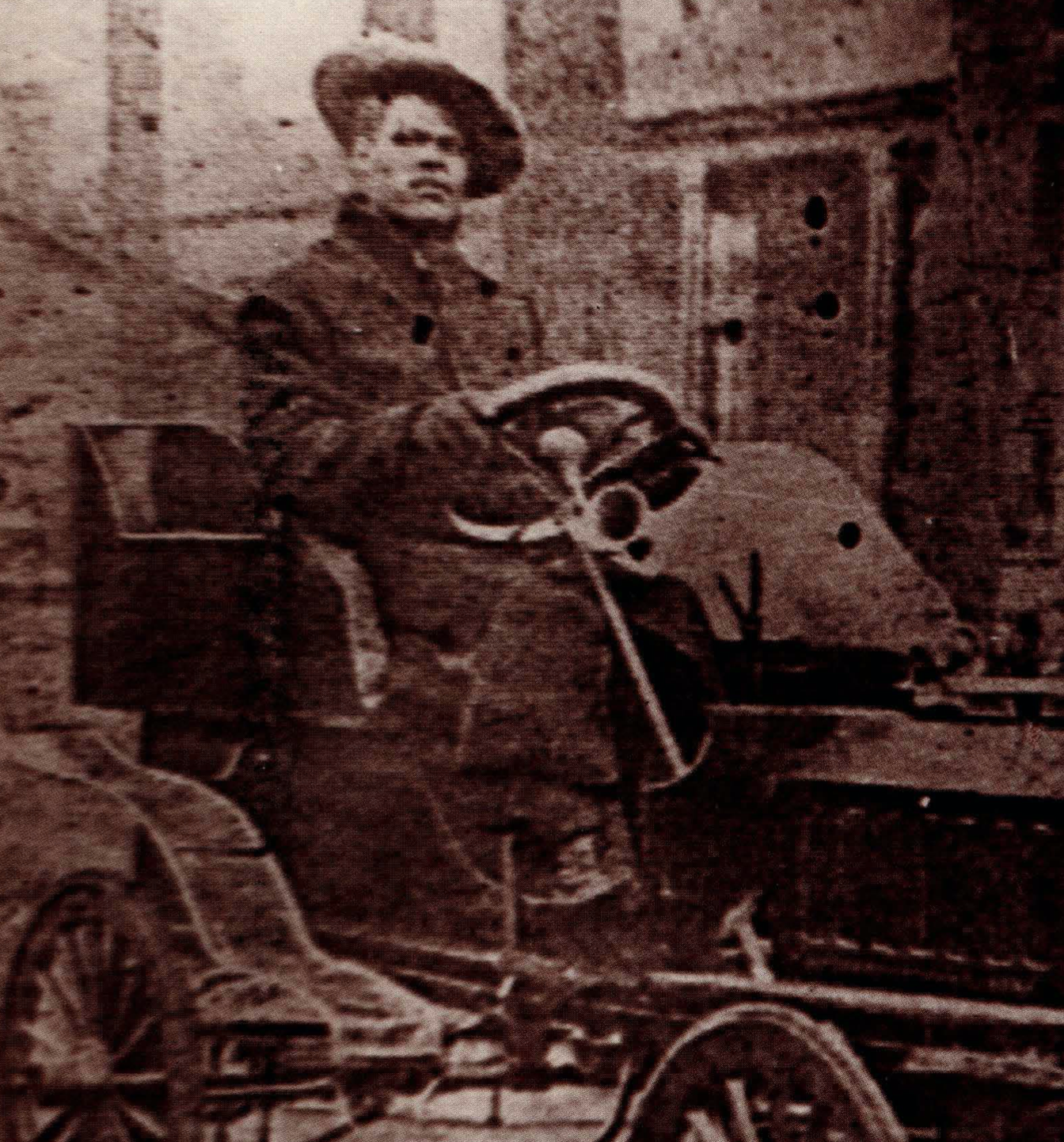

The first generation of his family to be born free, Majors began his life in Springfield, presumably at home, the same decade the railroad arrived a few blocks away. On the cutting edge of the time’s technology, he drove a defining moment in the city’s history when he took a car — that he built — around the city square in 1901.

That fact is generally what he’s remembered for in reflections on Springfield’s African American past. But there’s more: he was a successful business leader and an inventor, with a variety of patents to his name.

But the flip side of his story is what didn’t happen in Springfield — but did elsewhere.

Because Majors left.

News stories imply it was the horrific Easter Sunday lynchings of 1906 on the Square that led Majors and his wife, Myrtle, to St. Louis. They didn’t relocate immediately, but were gone by 1909.

Perhaps a way to process history is to think of what didn’t happen here because he decided to leave. Others did, too.

What if they had stayed? What if others had stayed?

What would Springfield look like today?

What else could have been accomplished here?

Majors’ start in Springfield

Majors — who was nicknamed Duck — began life in Springfield in 1879. While his parents, Peyton and Emma Majors, chose to stay in Springfield, they did not choose to come: they were born into slavery. It’s likely his father came from Tennessee; his mother was owned by the local Weaver family.

By the time Majors came along, the Civil War was over but cultural division was not.

“He was actually a contemporary of George Washington Carver. That same period of time saw a lot of development from the former slaves and their unique abilities in the Ozarks,” said Harold McPherson, who often heard about Majors from his family while growing up in Springfield.

Now 76, McPherson represents the fifth generation of his family to live in the Ozarks, the first of which arrived as enslaved people.

“The difference between the slaves of, say, southwest Missouri and the slaves of Mississippi or Arkansas is that the slaves in Missouri did not have a single chore that they had to repeat day in and day out,” he says. “They had a variety of skills as opposed to picking cotton or running a gin. These people developed skills that were beyond that of typical slaves of that period. Because of that, a lot of them were better educated and better skilled than a lot of the white settlers in that area, which I think caused some jealousy.”

Majors had a knack for mechanics

Majors lived near the campus of today’s Drury University, which was just six years old when he was born. Back then, Lincoln School — the first of three, the last now known as Lincoln Hall and part of Ozarks Technical Community College — was also located nearby and offered education for Blacks. That’s where Majors presumably attended school, but we don’t know for how long.

“He lived at 822 Washington, which is actually where the brand-new (Drury) business building is,” said Dr. Richard Schur, a professor of English at the university who has written about Majors. “The first school was maybe 200 feet from where we are, and then it moved to where the parking lot is behind the new business building.

“Any way you look at it, they lived two blocks from a school, and they had a lot of children. So it's conceivable that that was significant. The other thing that I wrote about — and this ties in with the idea of African American technological creativity — is that his dad always had jobs that were related to vehicles and transportation. I'm guessing you had to have some technical know-how to just make things work.”

Regardless of his level of education, it’s clear Majors had a knack for mechanics. Both McPherson and Schur note he worked at Springfield Wagon Company — a huge deal in its heyday for the Queen City — and was part of a city where a proportionally small but vibrant Black community existed. He also became a soldier as a teenager: in 1898, he was a volunteer for the Black American Company during the Spanish-American War.

Getting married and building his first car

On New Year’s Day in 1900, 21-year-old Majors married Myrtle Farrier. A newspaper notice shared several happy couples for whom the recorder, typically closed for the holiday, opened up the office so they could “begin the new year right.”

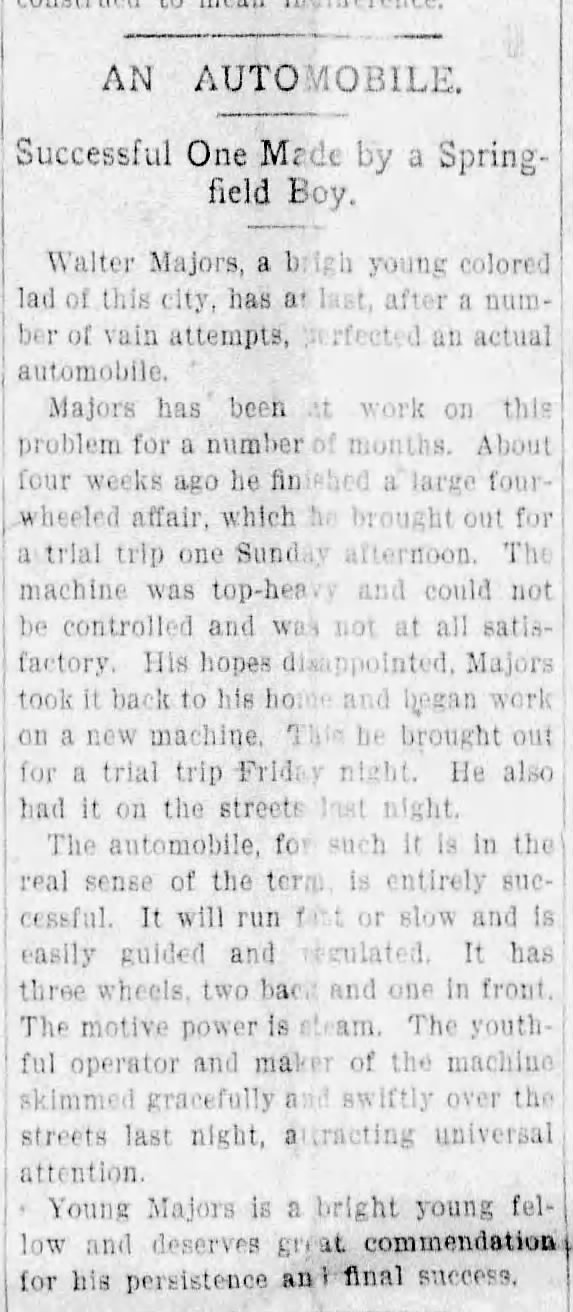

It was in this period that Majors built his first car — in Springfield, presumably the first that most in the city had ever seen.

“The automobile, for such it is in the real sense of the term, is entirely successful,” printed the Sunday Democrat, also noting that Majors had several months of attempts leading up to the win. “It will run fast or slow and is easily guided and regulated. It has three wheels, two back and one in front. The motive power is steam. The youthful operator and maker of the machine skimmed gracefully and swiftly over the streets last night, attracting universal attention.

“Young Majors is a bright young fellow and deserves great commendation for his persistence and final success.”

Majors’ entrepreneurial spirit continued to shine. In that period, it’s said he was involved in a bicycle shop. He worked with musical instruments. Two years after the car's creation, in 1903, he began a newspaper called The Statesman.

“Some of the prominent colored people of Springfield have started what they consider has long been needed in the city, a newspaper, managed and edited by members of their own race,” printed the Springfield Republican. “The journal will be called ‘The Statesman’ and will be published weekly.”

Turning cars into a career

By February 1906, Majors’ work with cars had grown to become a career. He owned a garage at 214 N. Jefferson Ave., just off the square. An ad in the Leader led with a simple headline — Automobiles! — and was followed by an opportunity for customers:

“Parties interested and having in view the purchase of an automobile can save money by calling on W.L. Majors,” the ad stated. It also listed the shop’s phone number, perhaps for when Majors was summoned by people “who had tried to motor to Springfield and failed to arrive,” as the Sunday News and Leader put it.

The city changed after 1906 lynchings

Less than two months later, the world changed with the horrific lynching of three innocent Black men on the Springfield square.

Horace Duncan, Fred Coker and William Allen died by Easter Sunday, hung from a tower on the town square. It was just one of several unjust lynchings and racial expulsions across the Ozarks at the turn of the 20th century. One example is in Pierce City, where in 1901 a lynching and murder led to Black residents being forced to leave town.

Given the ages of the lynched men in Springfield — according to The History Museum on the Square, Duncan was 20, Coker was 21 and Allen was described elsewhere as a “young man” — it’s possible that Majors knew them. At the time, he himself was just 26.

After the lynching

The late documentarian Katherine Lederer, who worked to share stories of Springfield’s African American community, was the author of “Many Thousand Gone.” In its introduction, the book says “That Easter weekend hundreds of blacks left Springfield forever. Left behind were business and property, farmland and livestock. In 48 hours, it was all over.”

McPherson disputes the fact that everyone left virtually overnight.

“The information that has been put out by that book ‘Many Thousand Gone’ gives the impression that there was this mass exodus of Black people,” he said. “And it just discredits or ignores the fact that many thousands stayed.”

Regardless of how many remained, perhaps other gradual changes came through the culture of a world where postcards depicting the lynching were printed and sold.

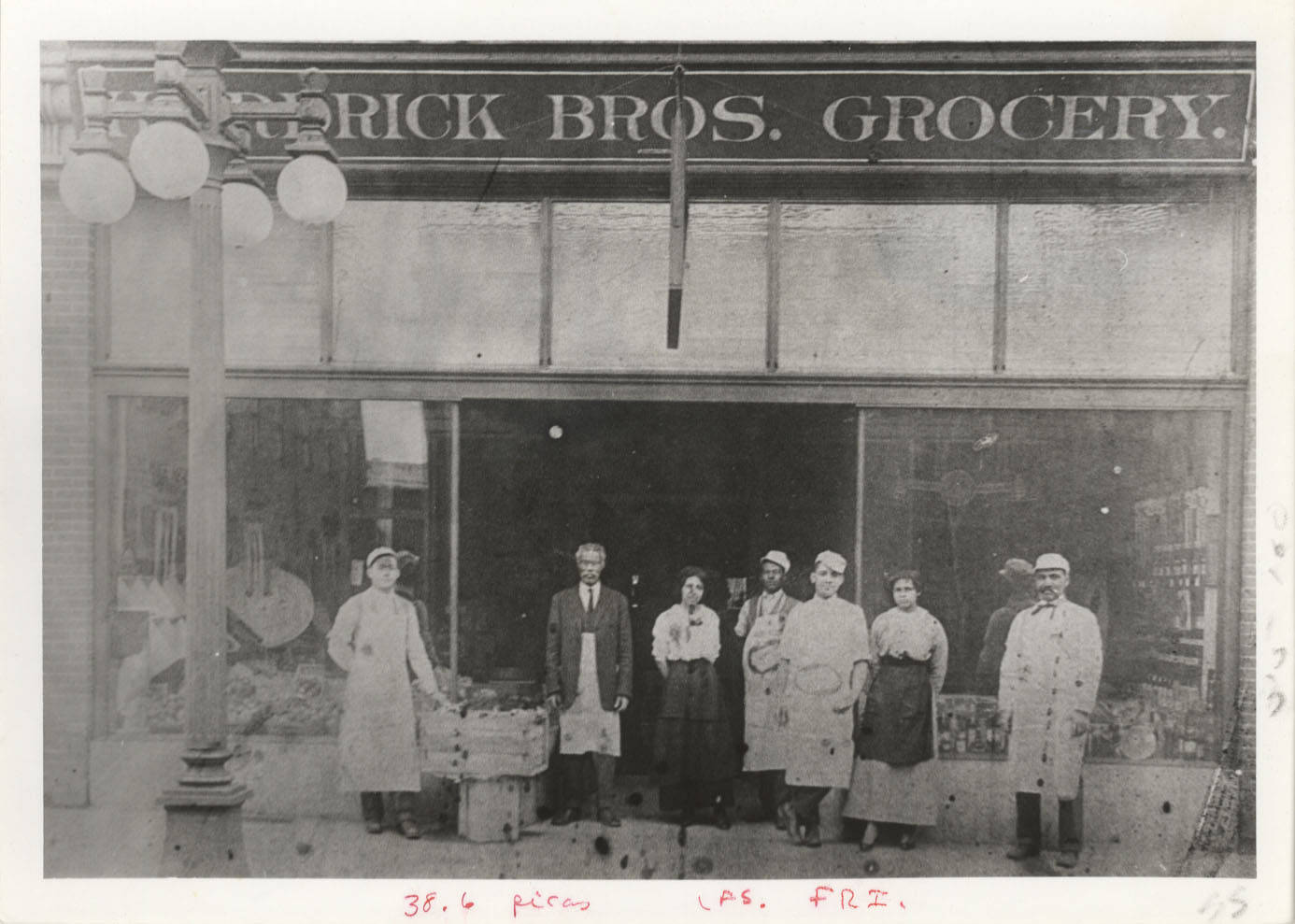

“The Hardrick grocery store used to be on Jefferson,” said Schur of a Black-owned market that was once Springfield’s largest retail grocery store. “Then after 1906, it eventually moved farther north, actually kind of where OTC is today, which is much more of where the Black community was, and there was less commerce there. I'm guessing it was probably a more integrated part of town, but I don’t know who the customers were.”

Majors did not leave Springfield immediately after the lynching, but he was gone years before the Ku Klux Klan purchased today’s Fantastic Caverns as a meeting place. Instead, he continued his automotive work near downtown, which was described in the newspaper the next year as “very prominent.”

To ground context in today: It was printed on a page near an image of the “main building” of the State Normal School, which was then under construction. Today, we know that building as Carrington Hall, the heart of Missouri State University.

“W.L. Majors is manager and proprietor of the business,” the article noted. “He has been nine years in the line and understands it in every detail. He has been connected with some of the leading firms of the country and is familiar with all makes of machines. He is a man of genial disposition and has become popular in business circles of the city. He is a firm believer in the great future ahead of Springfield.”

Legal troubles before leaving

Those words may have been true, but lasted little longer than it took to say them. Less than six months later, a full-page advertisement proclaimed that the Colonial Motor Car Company was open for business — with the same address as Majors’ former shop.

The Majors had moved to St. Louis.

It’s unclear if there was a specific reason for Majors’ decision to make the move. He had some legal trouble in the months leading up to the relocation. There are a few reports of him being stopped and fined for speeding; in 1907, a note of his latest fine reminded that the limit was six miles an hour, three lower than the state’s at nine, and that people must stop if driving toward a horse that was at all afraid.

But another latter moment was more serious: Majors was on trial for allegedly hitting an employee with a hammer over a payment dispute.

The outcome of the trial isn’t clear, either. But for whatever reason, he decided Springfield wasn’t where he wanted to be any longer. Was it the culture? Was it that his family had dwindled? One article claims he came to the World’s Fair in St. Louis in 1904 — was it simply the draw of a larger African American community that St. Louis offered? Was it concern over how an African American with violent “branding” would be treated in a community that just lynched three of his contemporaries? Did something else happen?

We don’t know, and likely never will.

Moving to St. Louis

The move was a great professional decision for Majors. Classified ads in St. Louis papers publicized the opportunity to hire him as a chauffeur or to train through Majors’ Mechanical Technical Chauffeurs’ Correspondence School, of which he was listed as president. The school offered a “complete course on French and American cars, including in course brazing and vulcanizing of tires; our instructions to drivers a long-felt need.”

By 1910, Majors opened a garage in St. Louis. He was still available for hire in 1912 when the St. Louis Post-Dispatch told that he would transport riders in a “first-class, 7-passenger car; operas and matinees, by the trip” or “joy riding” for $4 to $5 per hour. According to an online inflation calculator, that today would be in the neighborhood of $125.

The job was lucrative, but perhaps it also offered emotional benefits.

“It was not uncommon that African Americans were taxi drivers during this time period,” said Schur. “The reason why is it was sort of better to be a taxi driver than it was to be in a lot of other jobs. Because as a taxi driver, you at least have some independence. You don't have a boss who's sitting over you, you get to drive around the city, you get to be independent.

“Cars were considered to be very modern. One of the stereotypes about African Americans during this time period was African Americans were rural and couldn’t handle technology. There's really crazy arguments, especially from the 1870s-1880s, where all these demographers were saying that African Americans were going to die out because they couldn’t handle the modern world.

“Automobiles were key markers of social mobility — like physical mobility, but social mobility as well, because you can move around town. If you were a middle-class African American, you wanted to get a car, because then actually you didn't have to ride public transportation, which was demeaning to you.”

Into the beauty business

By 1915, Majors made a business move that changed his life forever: He went into the beauty business.

The decision presumably began with the acquaintance of Annie Malone, said to be one of the country’s wealthiest African Americans and proprietor of Poro College, a beauty-based empire. In a simplistic sense, the college educated students and sold proprietary products — but with hundreds of employees, its scope and size were significant.

“It also taught students how to walk, talk, and behave in social situations,” notes information on the Annie Malone Historical Society’s website. “During the early 20th century, race improvement and positive self-image were seen as a way to increase social mobility. By teaching deportment, Malone believed she was helping African American women improve their standing in the community.”

Perhaps Malone and Majors met when he worked as her chauffeur, how the Post-Dispatch mentioned he once served. Whether that presumably initial step is true or not, he ultimately impressed Malone with his business acumen and was hired to help lead the college’s business plan.

“Majors was the brains behind her mail-order business,” said McPherson. “He increased her sales by establishing this ability to ship stuff all over the country. She ended up having several shops; I think one in Chicago, one in St. Louis. She was a very wealthy woman at that time in St. Louis. I think she was looked upon as one of the wealthiest people there; she drove a Rolls Royce and she had a very huge house.”

It was a short-lived relationship, as the two were already in court over the contract in 1915, less than two years after it began. The case dragged out over 20 years, ultimately being decided in Majors’ favor.

Majors had at least five inventions to his name

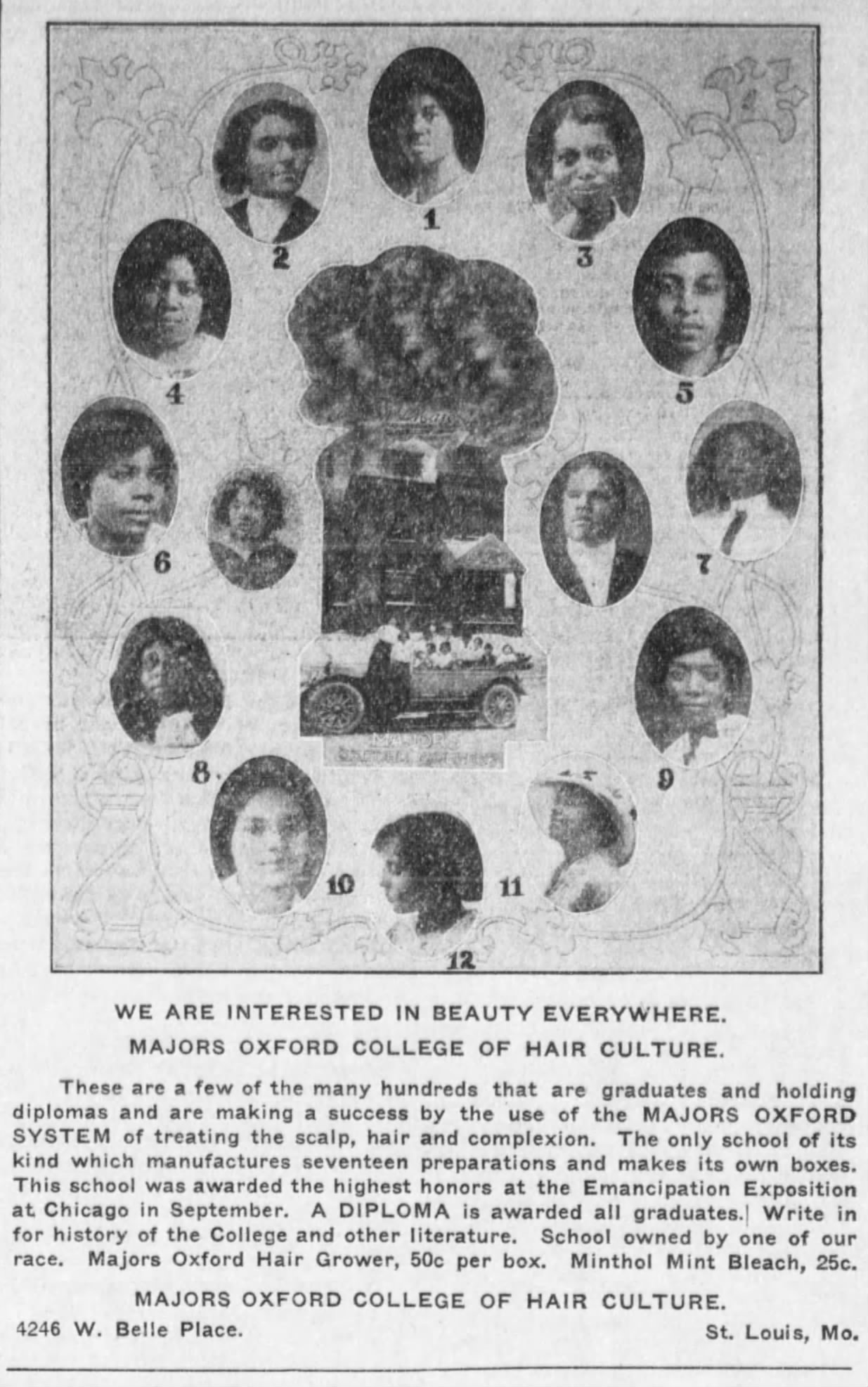

Long before then, Majors had other ventures into the industry. By 1916 he founded Majors Oxford College of Hair Culture, a St. Louis-based institution that educated beauty operators. A 1915 newspaper article in the Kansas City Sun — “one of the most prominent and influential African-American newspapers in the Midwest,” says the Library of Congress — notes he had at least five inventions to his name.

One was the Hot and Cold Air Machine, which was said to increase the oxygen that purifies the hair and scalp, helping protect operator and customer from infectious diseases. Across the page was an advertisement for Majors’ college, which boasted “seventeen preparations” and was awarded the highest honors at the Emancipation Exposition in Chicago.

“Among other things upon which he holds patents is a reproducing machine which will print three colors with one revolution of the drum, a safety device for automobiles to prevent accidents from skidding, a pay-as-you-enter device for taxicabs, and a high static machine for use on x-rays,” noted a Springfield newspaper in 1938. “Much of his experimentation has been with carburetors and his own car is equipped with a supercharger carburetor which he has designed and constructed.”

Whether he saw it as a mission to a greater cause or simply a business opportunity, learning was obviously important to Majors. It was also a tenet of the time, with education considered a step towards African American empowerment by leading educators such as Booker T. Washington.

Despite his clear intelligence and business savvy, the era also led Majors to suggest white people were important to success.

“I want my people to cooperate with the white people because, no matter what they may think, we can’t get along without them,” he reportedly said in 1938. “When I talk to the young people of my race I tell them that if they will apply themselves as good citizens and cooperate with the white people, then when they think they’ve got something they can go to their white friends and they will help them out. I tell them that any time they show they’ve got something that is superior, their white friends will push them, just as they did me.”

Those words, recorded in the newspaper, were ones Majors allegedly said to students at Lincoln School while visiting Springfield.

While there, he also shared about an oil burner he invented. At the time, the newspaper said, it was set to revolutionize the heating industry.

“He was invited to the Standard Oil laboratory and to the Kelvinator company experimental laboratory to demonstrate for other engineers what he has done and a company is about to be formed to manufacturer the device,” noted the Springfield newspaper.

Unanswerable questions — and links to today

Around a decade after that visit to Springfield, Majors died in 1949. He was 70.

The typed text on his death certificate gave him the last word on a life he worked hard to achieve: “Retired inventor,” it says.

Everything in life is dependent on circumstances. There’s no way to say that Majors would have had similar success if he’d stayed in Springfield. But given his ambition and drive, it’s hard to think he wouldn’t have had an impact.

Years ago, when McPherson was working toward the start of a museum and archive dedicated to local African American history in Springfield, he felt it should be named after the famed inventor.

The Walter Majors Institute, as he planned to call it, didn’t end up coming to be. The idea, however, emphasized the importance of his legacy.

“I’ve just been knowledgable because my family used to talk about Majors all the time when I was a little boy,” said McPherson. “I was ready to use Majors as the centerpiece for a local history of the Ozarks, with him being the focal point of it and then all the other stories that are around that time and before.”

Many years have passed since Majors died in 1949, yet his life is not that far away. Two years before Majors died, McPherson was born, his own life beginning under the shadow of segregation. On New Year’s Day in 1947, he entered the world at what was then Burge Hospital — and, still in the middle of the night, his mother was quickly told to leave.

“It was like 27 degrees, freezing rain and sleet, early morning,” he says. “They sent my mother and me to the streets at 4:30 that morning after I was born three hours earlier.

“They’d let you be born, but you couldn’t stay.”

‘They left for the same reasons'

Growing up in the 1950s and '60s, he initially lived in an all-Black neighborhood in Midtown Springfield. When the family moved a few streets away to Fremont and Division, it created a different reality.

“That was the first time I'd ever heard the word n*gger,” recalls McPherson. “I’m nine years old, walking down the street, and grown men would actually slow their cars down and try to intimidate me; call me the name, call me out. I'm like, ‘These are 25-, 30-year-old men — why am I a threat?’

“It got to the point where we saw it every day. I couldn't walk down the street without somebody saying, ‘Hey, you little n*gger!’ Me and my friends, we started carrying rocks. I discovered I could throw a rock faster than your car could go 100 feet.”

Like Majors, McPherson went to Lincoln School. When he was in second grade, the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education case ended segregation.

After high school graduation, he served in the Vietnam War and later moved to California to attend college. He did return to Springfield for a few years in the early 1980s. However, he felt compelled to ultimately leave five generations of his history in search of somewhere he felt more at home. Today he lives in the Kansas City area.

“I was able to expand my knowledge of the world by leaving Springfield. I didn’t want to be a martyr to ignorance,” McPherson said, reflecting on his expanded cultural knowledge and understanding he gained while being away. “The hatred, being called the N-word on a regular basis coming up — I didn’t have a lot of love. I didn’t want to be there. My parents, my grandparents, were all there, but it didn’t excite me.

“I didn’t have anybody I could have a conversation with, and most of the people I knew and grew up with that I could talk to had left. They left, too.

“They left for the same reasons.”

Resources

Advertisement, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb. 21, 1909

Advertisement, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 21, 1912

“An automobile: Successful one made by a Springfield boy,” Sunday Democrat, May 19, 1901

“Automobiles,” St. Louis Star and Times, Jan. 30, 1910

“‘Boy Wizard, now grown returns as negro genius,” Sunday News and Leader, April 24, 1938

“‘Genius’ rolled out early car,” Tamlya Beasley, Springfield News-Leader, Feb. 24, 1995

“Hidden History: The Memory of a Forgotten Inventor,” Erika Kelm, KOLR-10, Feb. 17, 2018

“Majors Automobile Co.,” Springfield Daily Leader, Oct. 2, 1907

“Many Thousand Gone,” Katherine Lederer, 1986

“Memories of Majors,” Emma Wilson, KSMU, Feb. 26, 2013

“Negro beauty doctor’s profits $25,000 a year,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 7, 1915

“Negro invents wonderful machine,” Kansas City Sun, March 18, 1916

“New Year’s Weddings,” Springfield Leader-Democrat, Jan. 2, 1901

No headline, Springfield Republican, Oct. 3, 1903

“A History of the Ozarks: The Ozarkers,” Brooks Blevins, 2021

“Patents asked for new gasoline feed,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Aug. 27, 1922

“Ready for business,” Springfield Republican, March 15, 1908

“Referee finds against negro beauty specialist,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Aug. 18, 1915

“White Man’s Heaven,” Kimberly Harper, 2012