OPINION|

Long before John Quinten Hammons became a millionaire and shaped the city of Springfield, he was a young man in pursuit of adventure. He found it in Alaska and captured the experience on film.

Earlier this month, I wrote a column about where Hammons is buried. It's in a small country cemetery near Fairview, Newton County, near the dairy farm where he grew up. He is buried next to his wife, Juanita K. (Baxter) Hammons.

In reporting that story, I learned that John Q. Hammons' first name is not “John,” it's “James.”

He was one of some of 10,000 men who worked in the Alaska Territory — the sparsely populated, rugged region of North America.

Keep in mind, Alaska did not become a state until 1959.

Also, John Q. would not marry Juanita until 1949.

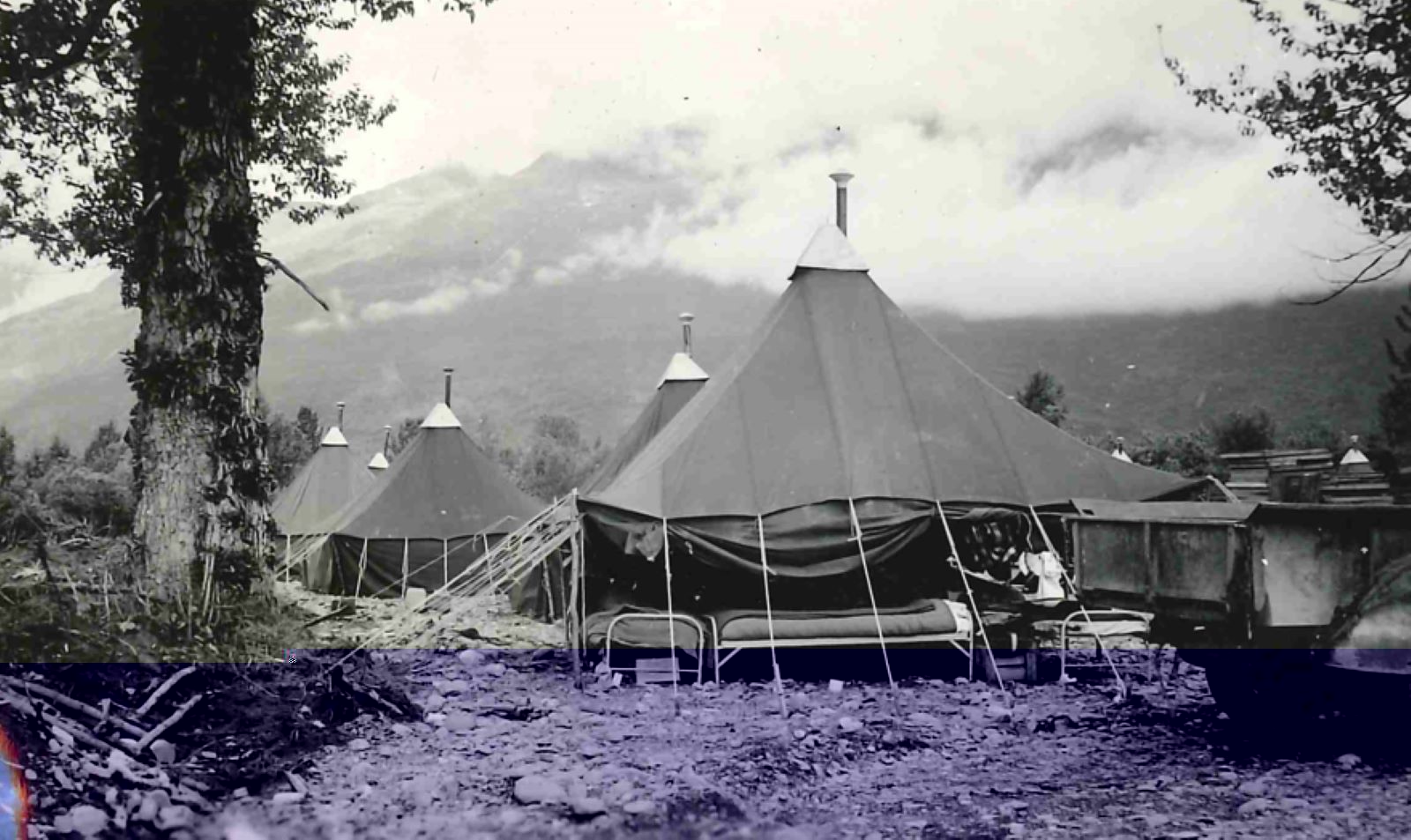

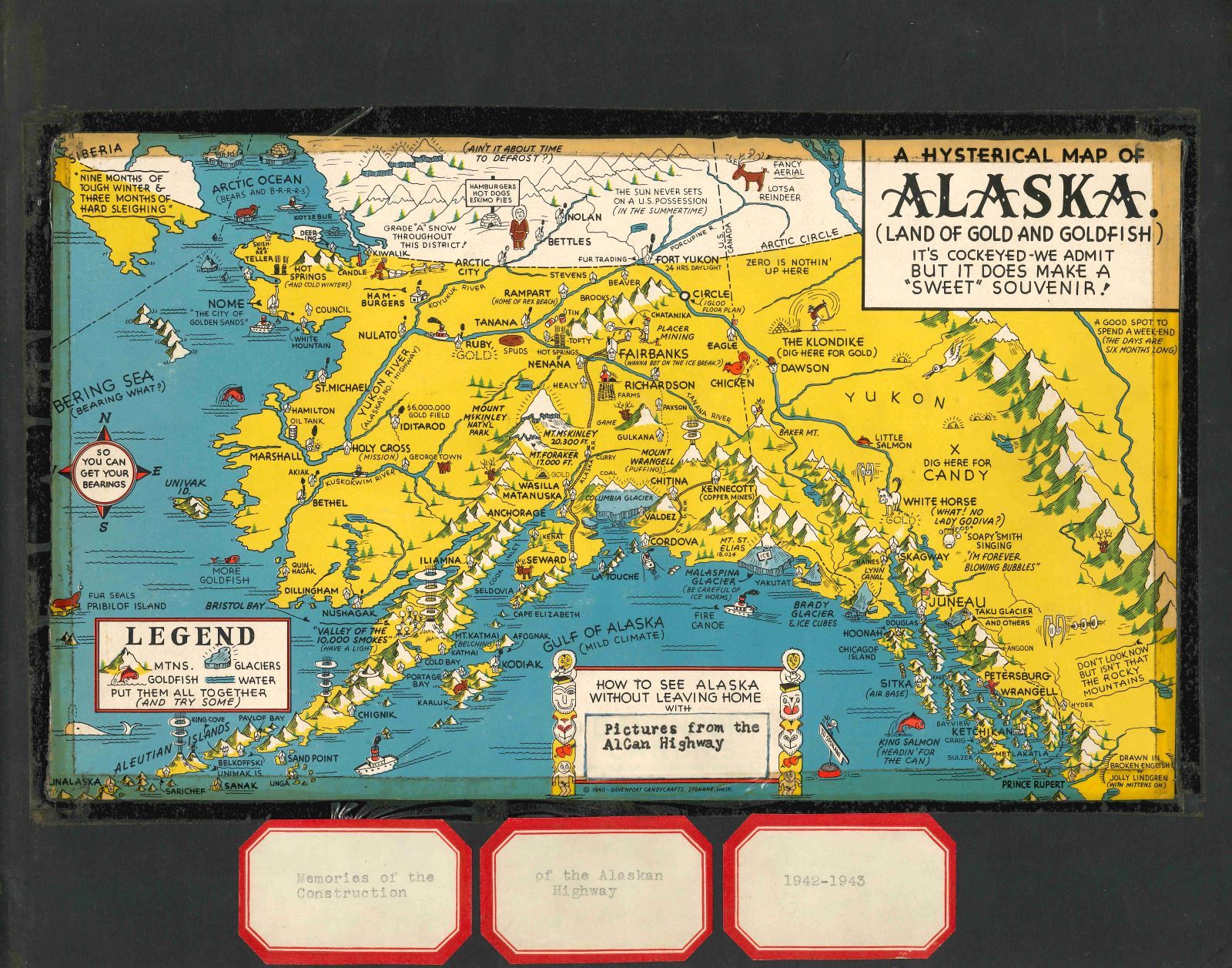

The second thing I didn't know was that as a young man in 1942-43, he lived and worked in Alaska and Canada helping to build the Alaska Highway, also known as the Alaska-Canadian Highway or ALCAN Highway.

At a young age he financially supported his parents

When I visited his gravesite, I saw that his time in Alaska is noted in a brief biography of his life carved in stone.

The ALCAN Highway was built mostly by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers with the cooperation of the Canadian government. The United States footed the bill because it wanted the road for military reasons, but Canada had to give approval. A private construction company was hired.

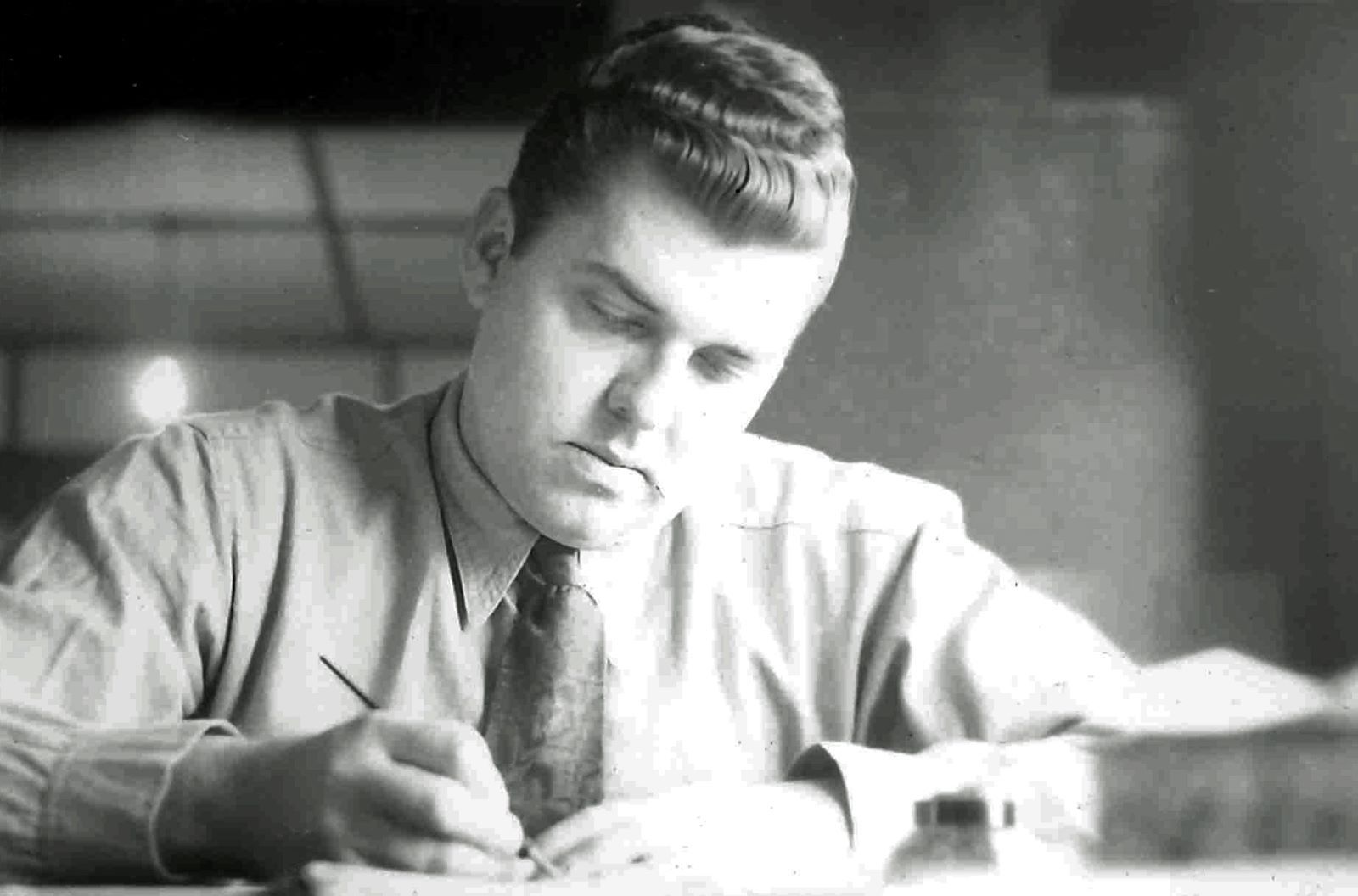

Before heading off on his young man's odyssey, Hammons taught and coached at Cassville Junior High School for two years. He graduated from what was then Southwest Missouri State Teachers College.

He was supporting his parents, James and Hortense, who lost the family dairy farm just outside of Fairview during the Great Depression.

Hammons, whose wealth in the 1980s would be estimated at $300 million, was ready for a change. He was ready to explore.

A May 2, 1951 story in a former Springfield publication called The Bias, in which Hammons was interviewed at age 32, states:

“After two years of teaching, he found that it failed to satisfy a certain adventuresome streak he had discovered in himself, and in 1941 he signed up with a field representative of a construction work company on the Alaskan Highway as a cost accountant on the project.”

As a cost accountant, he spent much of this time behind a desk.

MSU's special Hammons archive collection

Hammons explored Alaska as much as possible, taking hundreds of photographs. Many of them are part of the Missouri State University Library's Special Collections and University Archives.

The only reason I know about this collection is because I work on the MSU campus and while walking to the Daily Citizen office recently, I bumped into Thomas Peters, dean of MSU library services. He had read my story on where Hammons is buried and suggested I might want to take a look at the collection.

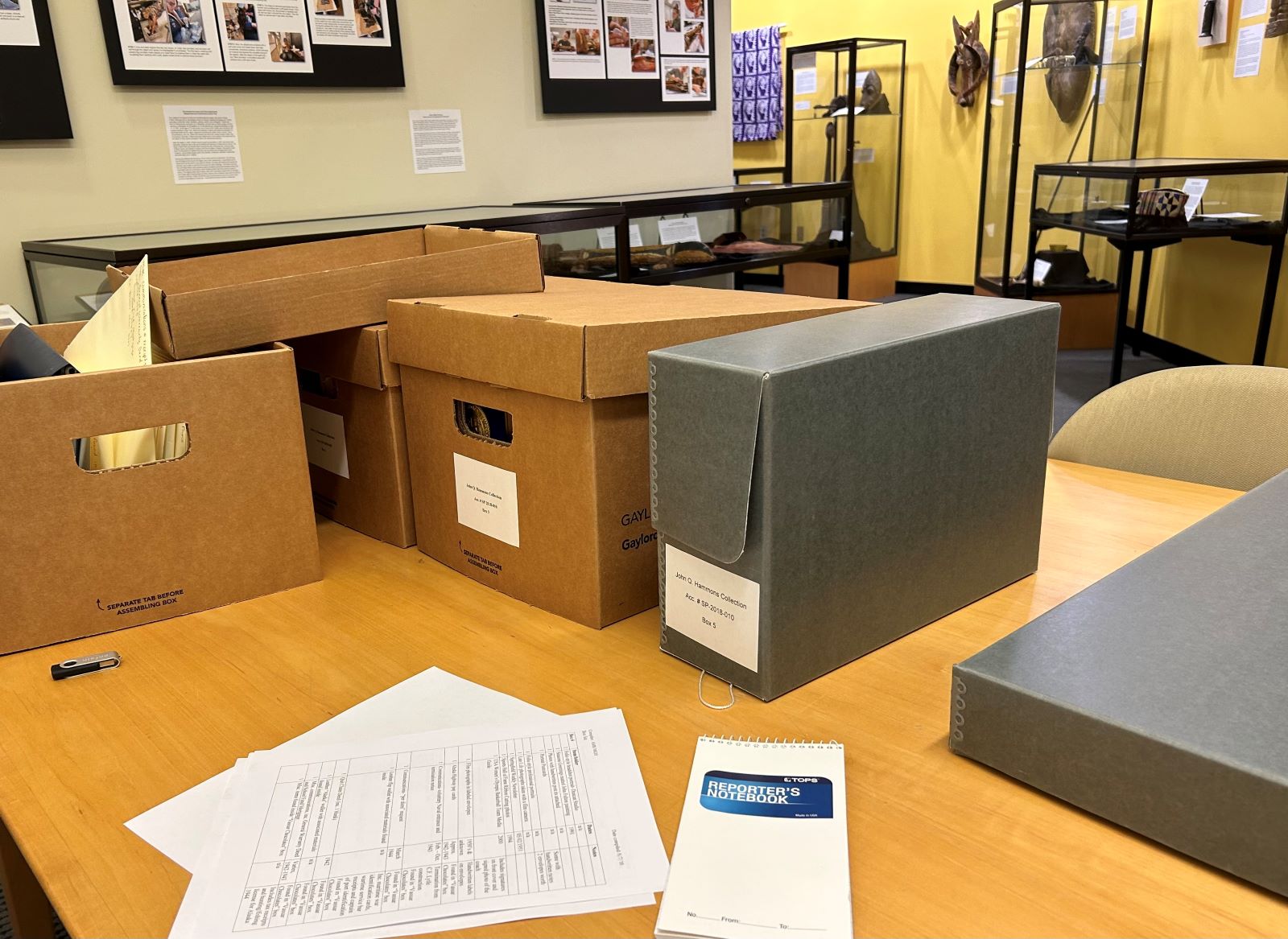

The good folks at the special collections office hauled out five boxes for me to peruse. Their contents are indexed. I looked only at the Alaska years.

Archivist Tracie Gieselman France provided me with a thumb drive with photos Hammons took while in Alaska.

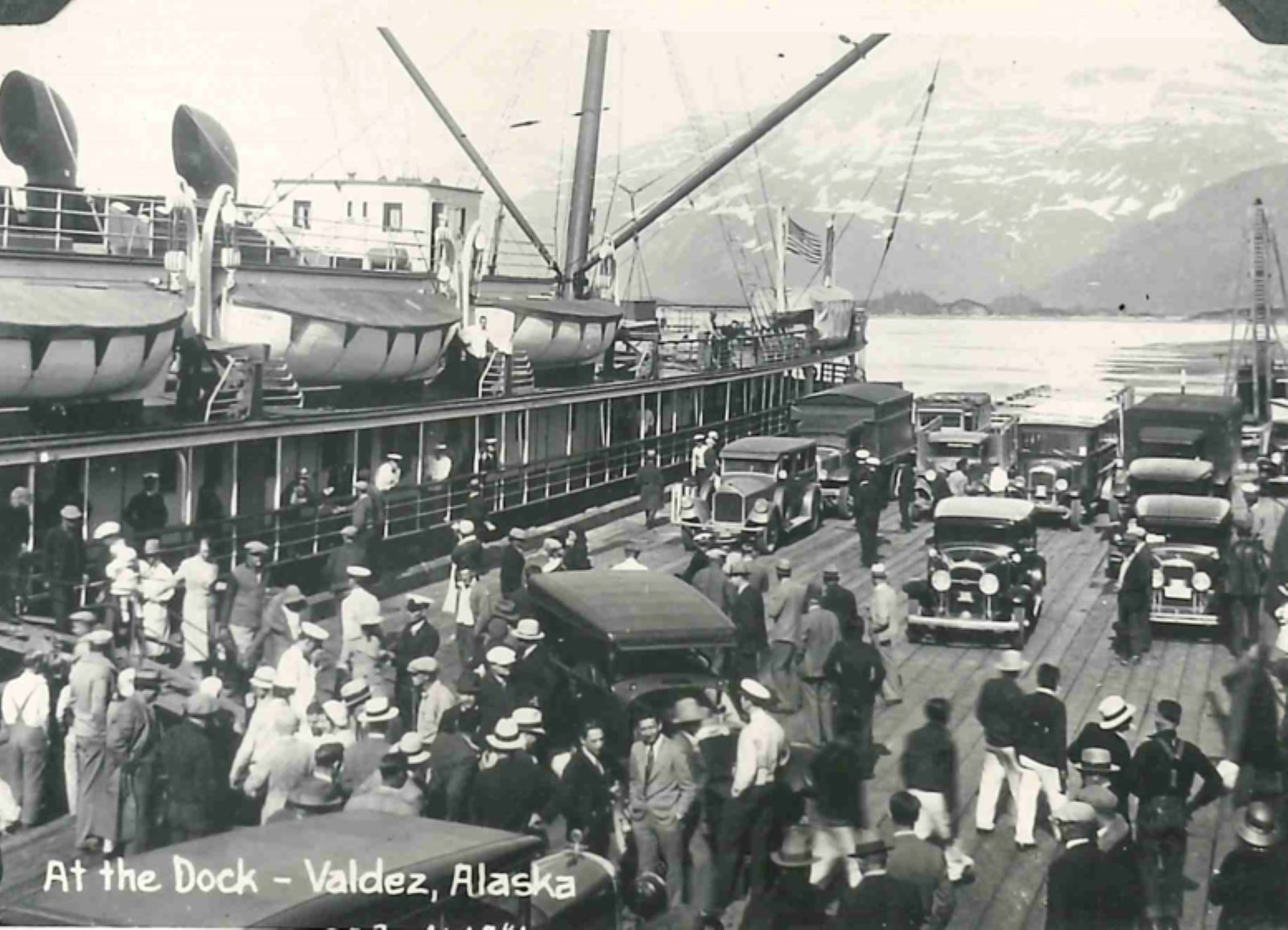

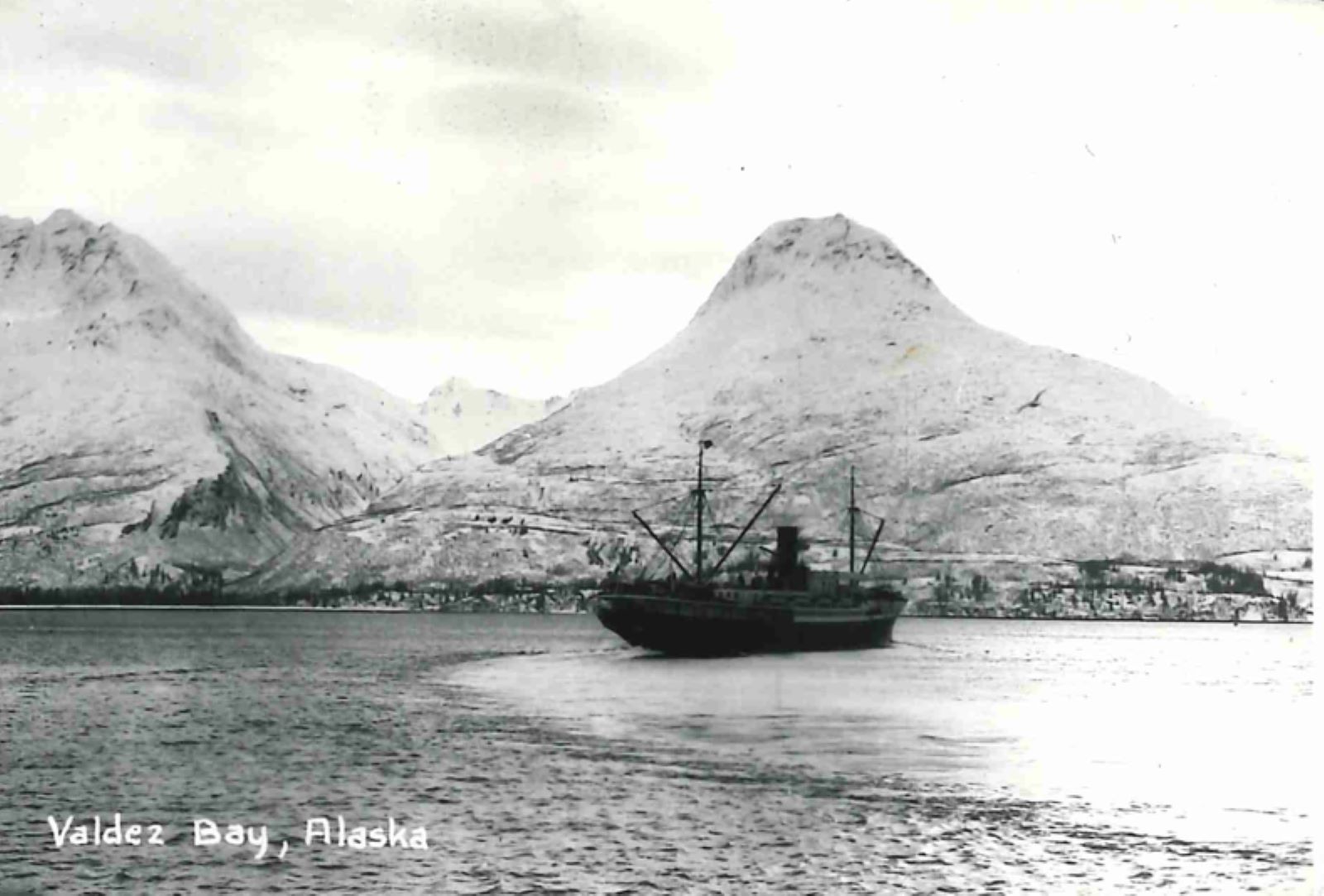

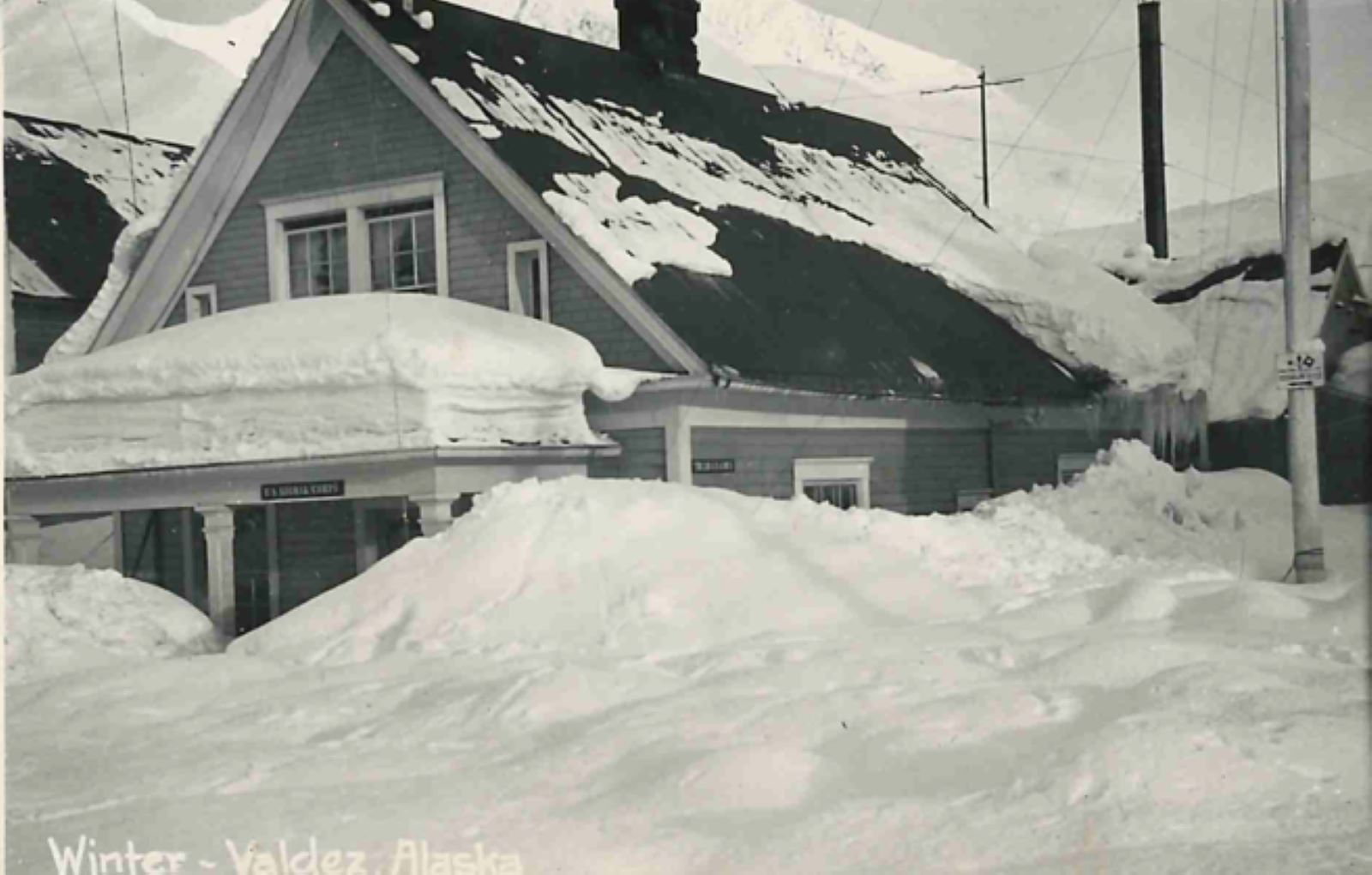

Hammons photos provide breathtaking views of Alaska, the mountains, the abundant snow, the men building the highway, some of the indigenous people and we get to see what the towns of Fairbanks and Valdez looked like 80 years ago.

But once again, a mystery about Hammons' name pops up.

Last week, as I mentioned, I learned his real first name.

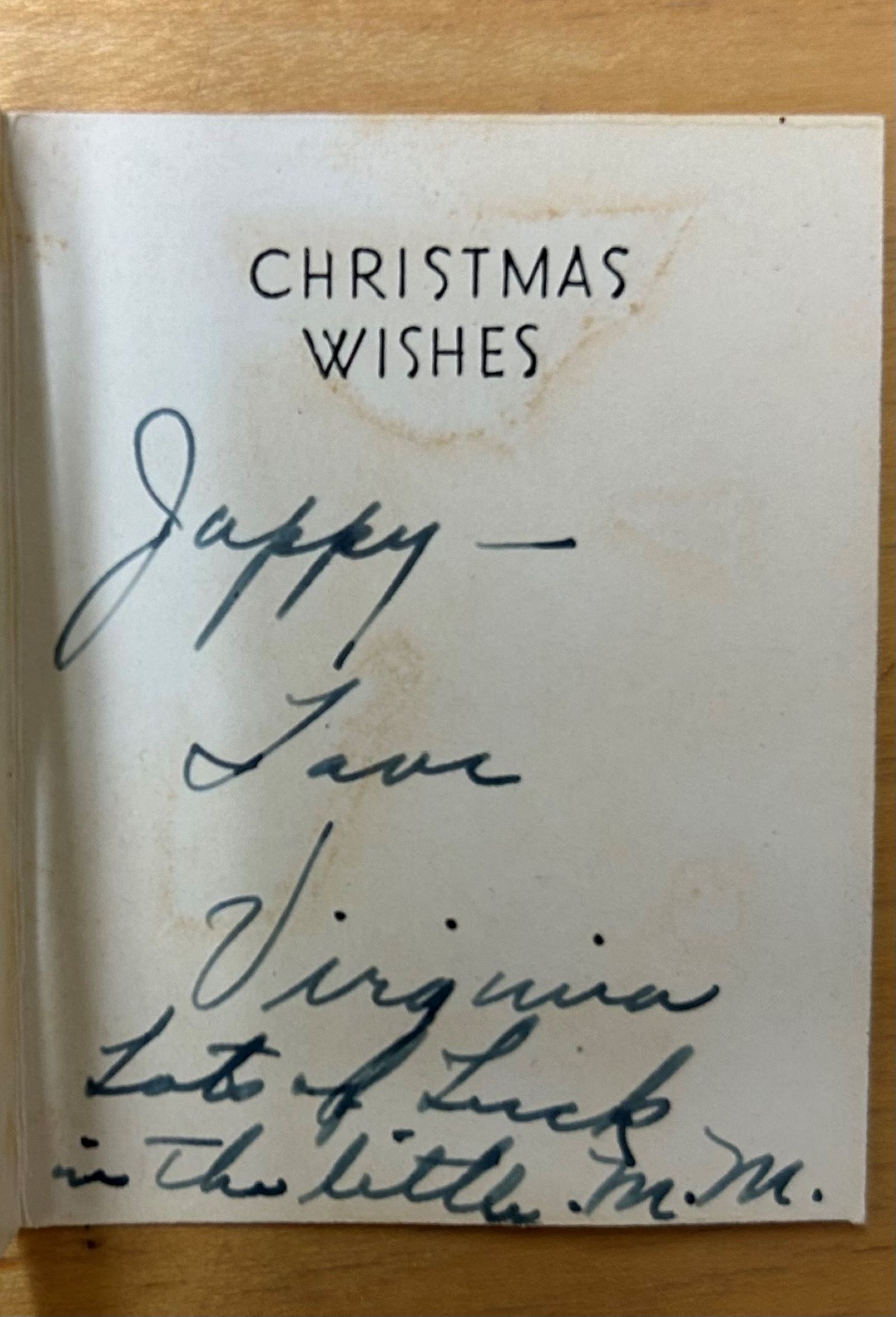

This week, I learned that he had a nickname in Alaska. It was “Jappy,” sometimes spelled “Jappie.”

I don't know the origin of the nickname, although the United States was at war with Japan at the time.

I asked John Moore, former longtime president of Drury University, who gave the eulogy at Hammons' 2013 funeral. Moore had never before heard of the nickname.

Part of collection is his Alaska scrapbook

Hammons compiled a scrapbook on his time in Alaska. It's part of the special collection housed at Missouri State University's Meyer Library. The scrapbook includes many of his photos, newspaper stories about the highway construction project and assorted stories about Alaska, including one about a hunter killing the largest grizzly bear ever recorded. Hammons also had newspaper clippings in his scrapbook of advertisements for taverns, hotels and an occasional clip of news from Neosho, Missouri, not far from Fairview.

The pace of construction of the highway increased when the Japanese invaded the Aleutian Islands, at the far western tip of the U.S. Alaska Territory.

For you history buffs, the United States paid $7 million for Alaska, or 2 cents an acre. This was in 1867.

The U.S. bought the land from Russia at the urging of Secretary of State William H. Seward, the man who back in 1860 went to the Republican National Convention in Chicago expecting to become his party's nominee for president. Instead, he lost to Abraham Lincoln and became once of Lincoln's closest friends and a trusted advisor.

The skeptics called the purchase “Seward's Folly” or “Seward's Ice Box.”

The Alaska Highway technically was completed in 1942, but it wasn't usable by general vehicles until 1943.

Oddly enough, when it was finished it was thought to be 1,700 miles long. Today, it measures 1,387 miles, because it has been realigned and straightened in places.

After highway project, John Q. joined the Navy

Once the road was finished, Hammons joined the U.S. Navy. According to that 1951 story in The Bias, Hammons circumnavigated the globe twice.

For more about the life of John Q. Hammons, I recommend a January 2019 profile of Hammons that appeared in Biz 417 magazine, although it makes no mention of Alaska.

Susan M. Drake wrote a biography of Hammons called “They Call Him John Q. A Hotel Legend.” It was published in 2002. I have not read it.

This is Pokin Around column No. 155.