OPINION|

Boys and girls, lawyers and paralegals, plaintiffs and defendants throughout Missouri!

Let's play Redaction!

We'll start with the name of former Glendale High School assistant football coach Ben Mauk.

Confidential or not?

Yes! The words “Ben Mauk” are confidential. Redact them. Ben Mauk. Strike them from public view.

How about his father, Mike Mauk? Sorry. Mike Mauk. Mike Mauk.

Again, confidential! Remove them!

How about these two words: “Nate Thomas?”

Redact! Blacken them! Nate Thomas.

Same for “Sean Mabins” and “Darline Mabins.”

Delete and delete! Sean and Darline Mabins.

And so it goes.

Indeed, these names and many names of coaches and athletic directors were stricken from a petition filed Aug. 28 by Bolivar attorney Jay Kirksey. It's all part of the filing process and new and greater emphasis on redactions across Missouri.

Judge needs to know, but public doesn't

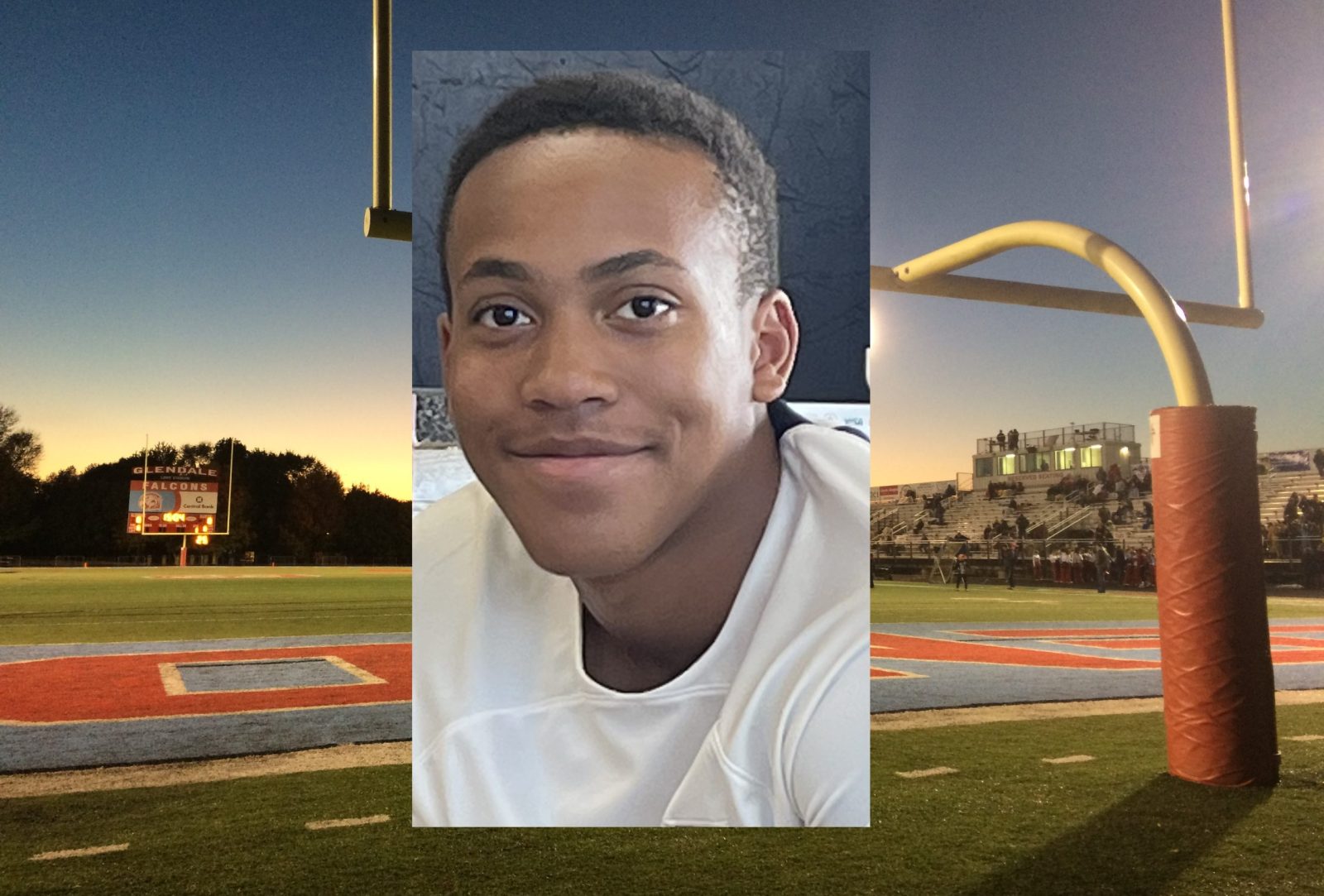

Kirksey went to circuit court this month to successfully argue that high school football quarterback Kylan Mabins should be allowed to play football at Glendale this fall.

Mabins had transferred in March from Kickapoo, where he started as quarterback his sophomore and junior years.

Of course, per Missouri law, Kirksey submitted an unredacted copy to the court because, after all, the judge has to make sense of these pleadings. The judge needs to know, for example, who Kickapoo's head football coach is. It's Nate Thomas.

But me and you, as members of the public, we don't see that clean copy because... well... because... well... It's all been redacted.

Well, I guess it's because we're stumbling through life without Juris Doctors degrees and, as a result, would never be able to make sense of what's going on even with the names before us.

I've seen redacted documents before; but the names of football coaches?

My first reaction when I saw the petition for a preliminary injunction was that I had mistakenly received a redacted copy of the missile-launch codes President Biden carries.

It also reminded me of the time when XXXXXX and XXXXXX, his illegitimate child, went to the massage parlor named XXXXX‘s XXXXXX, in the Catskills, where XXXXXX roasted wieners with Vladimir Putin.

See what I mean?

I'm accustomed to seeing redacted court documents. Colleague Jackie Rehwald and I read 150 probable-cause statements while reporting the Hauxeda series on domestic violence called “Living in Fear.“

By law, the names of domestic violence and sexual assault victims — and all other identifying information — must be redacted in documents made available to the public. I certainly understand that.

But why redact the names of football coaches in a civil proceeding?

Are we concerned a witness will be whacked?

You redact; I redact; we all redact

In my opinion, we are entering a new world in online information regarding Missouri courts. The portal to state courts is Case.net.

The Missouri Supreme Court has taken a step forward in providing access to public information on the courts via personal electronic devices like phones and laptops.

Reporter Rehwald wrote about this in July.

New rules that apply throughout Missouri went into effect July 1. The expanded access will go into effect Oct. 22 here in Greene County. But only documents filed after July 1 can be accessed via personal devices.

The way things are now — and have been for years — is that basic case information is available via personal devices but members of the public have had to go to the circuit clerk's office to see most actual documents and not just the summaries of the type of documents filed.

For instance, if you want to see a probable cause statement, which basically explains why an officer believes a suspect broke the law, you have to trek downtown to the office.

In expanding access, the Missouri Supreme Court has also, in my opinion, taken a step backward in this process by focusing on redaction. There are now four state forms associated with the redaction process: motion to correct redaction; redaction certification; confidential redacted information filing sheet; and application to inspect confidential court records.

The high court's rationale seems to be that since more public information will be readily available to the public there should be greater focus on redaction.

It's presented as a good and healthy thing, like brushing your teeth: You redact; I redact; we all redact.

It generally is a good and healthy thing. I'm all for making sure Social Security numbers, credit card numbers and dates of birth are not revealed in public records.

But redacting all the names in a civil proceeding regarding a high school football player seems silly to me and makes the court system less open and less transparent.

Redacting the names was following the law

The Mabins petition was filed by the law office of Jay Kirksey of Bolivar. His petition was then redacted, he tells me, by his paralegal.

Kirksey said the new emphasis on redaction has made the whole process of filing a document more laborious.

He assures me that, first, he believes in court openness and transparency. Second, his paralegal had to redact the names of all those football coaches and athletic directors because that's what the law requires.

“I am going to abide by the law,” Kirksey says.

And when in doubt, he says, he might occasionally err on the side of doing more redaction than the law requires.

The new rules apply not only to attorneys, but to those filing “pro se,” meaning they represent themselves.

The state's high court provides a list of what must be redacted. In addition to those pieces of information already mentioned, it includes passport numbers; financial institution account numbers or passwords; and credit or debit card numbers or passwords.

Names of potential witnesses redacted, too

Here's where things take a turn. Also to be redacted are:

“Names, addresses and contact information of informants, victims, witnesses, or persons protected under restraining or protection orders.”

They key word there is “witnesses,” Kirksey says.

Many of the redacted names in his petition were people who later were witnesses.

I attended the hearing over two days and some were not witnesses, including Ben Mauk. Ben Mauk.

In other words, lawyers like Kirksey, who want to follow court rules, are redacting the names of key people in civil filings because they might later be a witness, leading to real sentence such as this:

“Kickapoo represented that REDACTED was REDACTED, and REDACTED had worked with Mabins in 7th grade.”

It certainly lacks the rhythm of a David Harrison poem.

I should note that this redaction rule regarding witnesses is not new.

Supreme Court of Missouri Rule 55 outlines the rules of civil procedure. It states redaction is required of witness names.

The end result of this focus on redact, redact and redact some more, I fear, will be greater access to Case.net via personal electronic devices to information that tells you that somebody sued someone about something.

This is Pokin Around column No. 135.