OPINION |

On Wednesday morning a 60-year-old man was lying on a blanket not far from the shoulder of Highway 160/West Bypass.

I was with colleague Jackie Rehwald, covering the clearing of a homeless encampment by the Greene County Sheriff's Office.

The man was startled when we approached and seemed nervous and fearful. We tell him we are reporters.

“I don't want my name in the paper, and I don't to be photographed,” he says.

Semi-tractor trailers rumble by. Several shopping carts filled with sodden possessions are around us. It rained hard Monday. Most of the items do not belong to him. They belong to the people who have already left.

There are several cats and many flies.

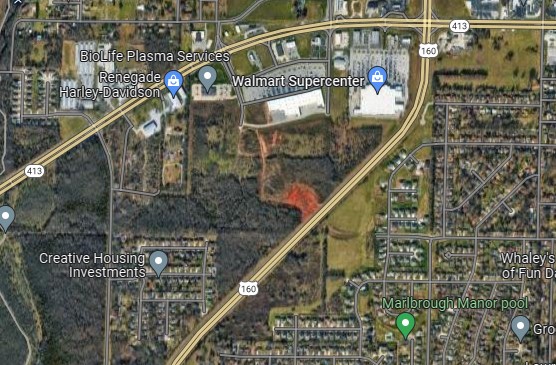

The encampment is not far from the Walmart at 3520 W. Sunshine St.

The sheriff's office has worked to clear out people and their shopping carts filled with possessions. A notice to vacate was posted Monday, Aug. 29. It states the land is owned by the Missouri Department of Transportation.

Man says he has lived in the woods 5 years

For five years, the man says, he lived in the wooded area south of Walmart. But the trees are gone now; the earth is being turned for a new development.

The residents of the woods were pushed closer to Highway 160 and, as a result, became more visible.

He tells us his first name is Lloyd. Because he won't give his full name, he is what reporters call an “anonymous source.” The Hauxeda tries to avoid the use of anonymous sources.

Jackie and I consult with editor Brittany Meiling about why he should be granted anonymity and — once we allow him to speak to us anonymously — how we should use the information he provides.

In a nutshell, since we don't really know whom we're really talking to we must try to verify as much as possible with other sources.

That's what I did, because what Lloyd told me was startling — and it opened my eyes to what happens when an unhoused person dies in Springfield.

He says his ‘wife' was killed up on Bypass

Lloyd tells us the last time he had a roof over his head was — and this is his best guess — in 2005.

He has lived in Springfield all his life, he says, other than the 17 years he spent in prison. He says it was for unlawful use of a weapon and drug charges.

Lloyd tells me something I didn't anticipate. On Dec. 5, 2020, his wife was hit by a vehicle and killed up there on the bypass. He says a seizure caused her to move in front of a passing vehicle.

He does not know what happened to her body.

No, he says, they were never legally married. They were just together a long time.

Not much personal info in an autopsy

Maybe this is one little thing I can do for him. Maybe I can find out what happened to her body. At the same time, I doubt Lloyd will ever see this story. I'm curious, too.

I ask him for her name.

I confirm the death of Marcie Lyn Brown, 39, with the Medical Examiner's Office. An autopsy was done after she died.

If you've ever read an autopsy report, you know there isn't much personal information. It is a litany of medical terms most people don't understand.

According to the autopsy: “When first viewed, the body is clothed in a blue shirt, gray pants, black shoes, black socks, blue hat, blue jacket, a pink shirt, red leggings and a black hair tie.”

It states she was “crossing roadway and laid down; some witnesses said she was having seizure activity prior to laying down; then was run over.”

It also mentions something that maybe Lloyd knew and didn't tell us or simply didn't know: a contributing factor in her death was “methamphetamine intoxication.”

Where does the body go?

What happens when an unsheltered person living in the woods dies?

Where does the body go?

Are most loved ones like Lloyd? They simply don't know?

The answer is that the body goes to the Greene County Medical Examiner's office. The office has 30 days to try to find a relative, says Tom Van De Berg, chief forensics investigator.

The office works with the Herman H. Lohmeyer Funeral Home to try to find family.

At Lohmeyer, it's part of community service

Most funeral homes decline to offer this assistance, Van De Berg says. That's because it's not profitable.

“We feel it is a part of our service to the community,” says Kent Franklin, funeral director and embalmer at Lohmeyer.

Lohmeyer will run death notices on its website and will place ads — not full obituaries — for 10 consecutive days, if needed, in the News-Leader, Franklin says.

The hope is that someone in the family is notified of the death.

The News-Leader, also in service to the community, does not charge for these death notices, he says.

The notice for Marcie Lyn Brown ran two days and then stopped because someone from her family contacted the funeral home, Franklin says.

It was her mother, who lives out of state. Franklin does not know how she found it.

Oftentimes, no one claims the body

Often, he says, no one responds.

“We just live in a society where people do not communicate with their family like they used to,” he says. “It's not just homeless. There are also families walking away from loved ones in the hospital because of bitterness, financial difficulty or hate.”

When no one steps forward, Franklin says, Lohmeyer cremates the body and then charges Greene County a reduced rate of $400.

Franklin says that in trying to find relatives for Marcie Lyn Brown, the funeral home learned she had a husband, one she was legally married to, who reportedly was living in a homeless camp in Ohio. They were unable to contact him.

Van De Berg says that throughout Springfield, the cremation charge at various companies ranges from $800 to $2,300.

“We suggest people contact as many funeral homes as they can,” he says.

Ashes go back to medical examiner's office

When no family is found, Lohmeyer does the cremation, and the ashes are returned to the medical examiner's office.

The office no longer scatters them at the Alms House Cemetery in west Springfield off of Division Street.

That practice made it forever impossible to provide them to loved ones who might someday come forward and ask for them, Van De Berg says.

Instead, roughly every six months someone from the medical examiner's office drives to the Wildey Odd Fellows Cemetery in Washington.

“I just took 59 sets of ashes there last month,” Van De Berg says.

Odd Fellows: In service to bury the dead

The columbarium building at the Wildey Odd Fellows Cemetery in Washington is dedicated to holding unclaimed cremains. A columbarium is where urns of cremains are stored.

The Odd Fellows built it in 2013, after learning that funeral homes often have dozens of cremains on their shelves, sometimes for years.

The Independent Order of Odd Fellows is a fraternal order created in 1819. It was formed to “visit the sick, relieve the distressed, bury the dead and educate the orphan.”

The organization, Van De Berg says, will release ashes to family members who perhaps did not know a loved one had died years earlier and was cremated.

But that's not what happened to Marcie Lyn Brown.

Her mother found out she had died and she wanted and received her ashes.

This is Pokin Around column No. 58.