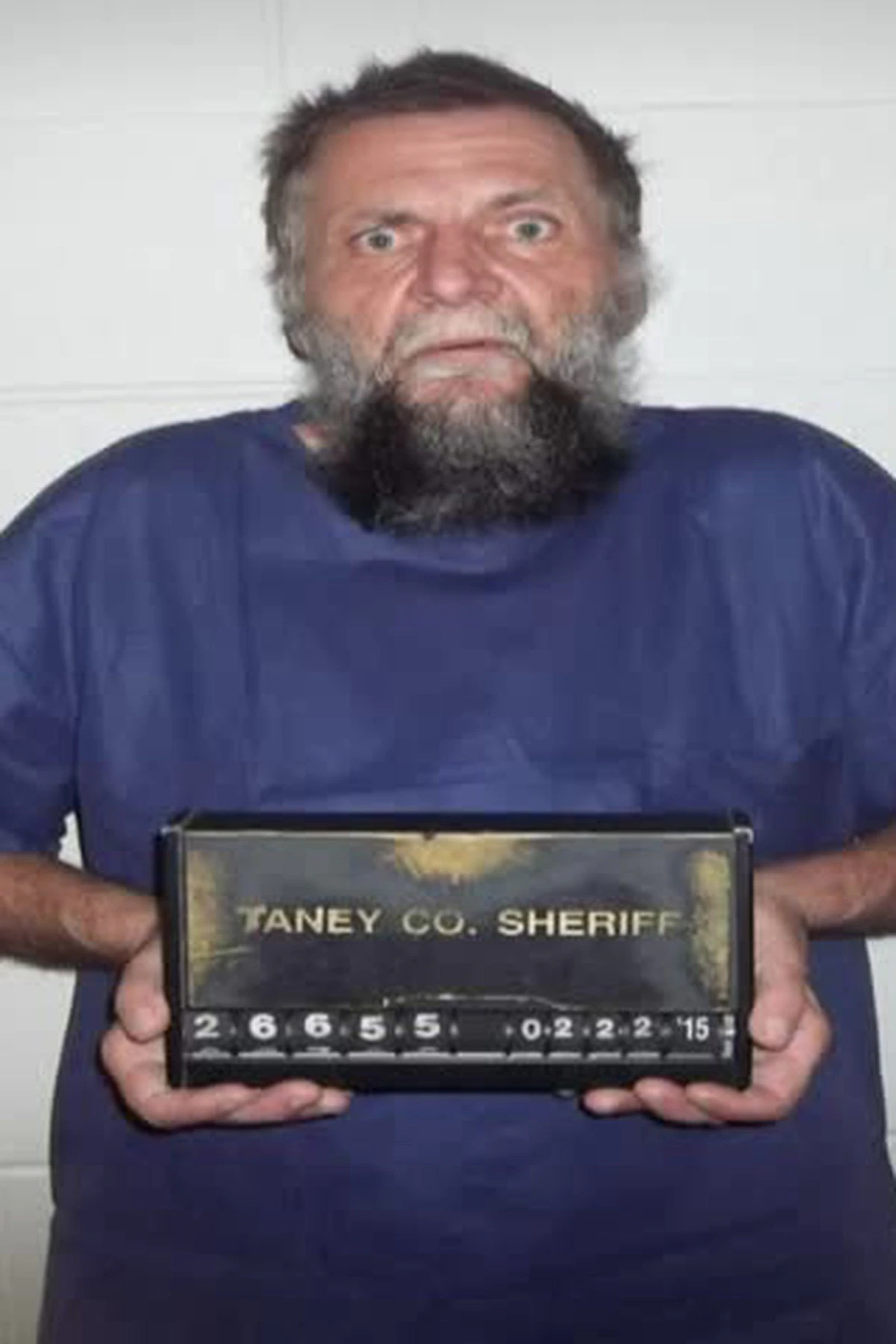

John P. Roberts, accused of killing 6-year-old Jasmine Miller in 2015, in Branson, will likely spend the rest of his life in the custody of the Missouri Department of Mental Health.

According to a court order that should have been a public document — but mistakenly was not — Circuit Judge Jason Brown has determined that Roberts, now 62, is unlikely to ever be mentally competent enough to understand the murder charge against him and cooperate with his defense lawyer.

That Oct. 14 order was made available to the Hauxeda Friday.

“The Court finds that Defendant has demonstrated by a preponderance of the evidence that he remains incompetent to proceed, and, additionally finds there is no substantial probability that he will be restored to competency in the reasonably foreseeable future. Accordingly, as required by statute, the Court announces its intent to dismiss the charges, without prejudice, pending other proceedings.”

For this story, Michael Cordonnier, the presiding judge in Greene County, looked into the case in response to my questions and discovered the error which mistakenly made online information on the case unavailable to the public.

Although unlikely, if Roberts is ever deemed mentally competent to stand trial, the murder charge can be re-filed.

At some point, the case was removed from CaseNet, Missouri's online data management system for court filings, when it should not have been.

The error occurred in the office of Taney County Circuit Clerk Amy Strahan.

The case was removed from CaseNet in September 2019. But it was returned to public access today, Friday, Feb. 18.

The online docket made available — once again — showed 32 entries in the case since September 2019 and one hearing on Roberts’ mental competency. A case review is scheduled for March 4.

Brown’s order stated he intended to dismiss charges but only after Roberts has been officially placed in the care, custody and control of the Department of Mental Health.

That has not happened yet. But the judge’s order was mistakenly coded to indicate that the charge was dismissed.

Once that happened, the case was immediately removed from CaseNet. State law requires that a criminal case be removed from public view on CaseNet once charges are dismissed.

Roberts was living in what was then the Windsor Inn, an extended-stay hotel where many low-income people lived.

Jasmine resided in the same building with her mother and step-father. Her naked body was discovered under Roberts' bed. She had been strangled to death.

It was a heinous crime and shocking news.

The most recent news story I could find was from Sept. 23, 2019, by News-Leader reporter Sara Karnes.

It said: “A man accused of strangling a 6-year-old girl is going back to a state facility for more mental competency exams.

“Judge Jason Brown said John Roberts lacks the ‘mental fitness to proceed’ in a judgment filed Sept. 16. Roberts is charged with first-degree murder in the death of Jasmine Miller.

“‘(Roberts) lacks a sufficient, present ability to rationally understand the proceedings against him or to consult with and assist his counsel,’ according to the judgment.”

Why people have lost track of this case

As best I can tell, there hasn't been a public word about the case since the News-Leader story. Until now.

I have been trying since December to give you, our readers, an update on what has happened since then. It has been a difficult process.

I found the answer this week after I reached out to Brown.

The reason Brown, a Greene County judge (31st circuit), was presiding over a Taney County case (46th circuit) is because Greene County simply has more circuit judges. Greene County has six and Taney County has one and, currently, it’s Jeffrey Merrell who is the former Taney County prosecuting attorney.

Merrell was prosecutor when Roberts was charged; he was disqualified from hearing the Roberts case, and others, because of his former role.

To find an update on the case, I did what I always do. In December, I checked CaseNet, Missouri's online data management system for court filings. The case was gone. It had disappeared.

I am familiar with the story of Jasmine’s death and know of its impact on the community. When I was at the News-Leader, I did some reporting on the case.

Jasmine had had a rough life. Four days after she was born in Wichita, a representative from the Kansas Department for Children and Families came to check on her well-being.

And over the next six years of her life, child welfare workers in Kansas and Missouri continued to check on her health and safety, never finding enough evidence to conclude that she had — as alleged by hotline calls — lived among cockroaches or maggots or that she had been abused or neglected by those entrusted with her care.

That evidence for neglect was found only after she was killed in Branson.

The Children’s Division concluded that parental neglect played a role in her death.

A woman who once had unofficial custody of Jasmine told me back then that it was likely that Jasmine went to Roberts’ room because she hadn’t eaten in a while and was hungry.

When Roberts was first taken to the Taney County Jail, police said he was “disoriented” and that Roberts told them he was high on “devil poison” — methamphetamine — when he gripped the girl's neck “to scare her” for taking snacks from his room, documents said. He later told police he intended to molest the girl.

From 2015 to 2019, prosecutors and defense lawyers debated in open court whether Roberts was mentally competent. The issue wasn’t whether Roberts killed Jasmine; it is whether he knew right from wrong when he did it and whether he has the mental capability to assist the public defenders assigned to defend him.

Now, it appears the first question — whether he knew right from wrong — will never be weighed in a courtroom.

Back in December, once I noticed the murder charge was no longer on CaseNet, I called the current Taney County prosecutor, William T. Duston, and the person who I believe to be Roberts' current public defender, Bryan Delleville.

Since December, I have called and left a message for Delleville at least four times. He never responded.

Similarly, I left repeated messages for Duston.

I made it clear in my message to both that I wanted to know the status of the murder charge that might or might not be pending against Roberts.

Duston finally called me back over a month later, on Feb. 11.

He said the murder charge against Roberts was still pending.

“There isn't really any update, per se,” he said. “We have a hearing every few months about his continued mental capacity.

“Like I said, those hearings have gone on for the last few years.”

He said he did not ask that the case be removed from CaseNet and suggested I talk to Judge Brown and/or the Missouri Office of State Court Administrators.

As I said earlier, when I called Brown I heard back from Cordonnier, the presiding judge. Cordonnier was responsive and assured me that no one was trying to keep the matter from the press or the public.

He investigated and found out where the error occurred in the judicial process.

CaseNet uses 9 levels of security for online access

On Wednesday, I talked to someone in the Office of State Courts Administrator who was well-versed in CaseNet and who — ironically — did not want her name associated with the information she provided.

A judge can seal a case, meaning no one but the judge and some court personnel can access the information.

The word “seal” comes from a time when court documents were paper and they were stored in a file with a seal on it and, as best I recall, a note saying members of the public were not to break the seal.

We now live in a digital age and court documents are online.

On CaseNet, there are nine different levels of security regarding online access. Actually, there are only eight because, I'm told, Level 7 is not currently in use.

The person I spoke to – who did not want her name used – told me she would email me the description of each of the nine levels. She did not. I called her back to remind her and she did not respond.

But I do know this: Level 1 means the online file is open to the public. At the other end of the spectrum, Level 9 is for expunged cases, meaning the court has sealed the record and you would need a court order to pry it open.

In reporting this story, I discovered something else about CaseNet.

In the midst of trying to find out what had happened to the murder charge against Roberts, I noticed a News-Leader story this week written by reporter Gregory Holman.

Cordonnier presided over a civil trial in which a woman sued CoxHealth and CEO Steve Edwards. (Jurors ruled in favor of CoxHealth and Edwards.) Prior to and during the trial, the case had been removed from CaseNet.

Why?

Cordonnier, once again, had the answer.

But his response, to me, revealed a Catch-22 situation where a judge issues an order explaining why a case was removed from CaseNet but the public can’t find that order because the case was removed from Casenet.

Cordonnier removed the CoxHealth case from CaseNet about a month before the trial was expected to start.

He said this happens regularly because that’s when summonses are sent to prospective jurors. He said the case is always made public again on CaseNet when it's resolved.

Some reporters know judges often do this. I did not.

Judges don't want potential jurors searching CaseNet after getting their summons wondering what case they might be assigned to if chosen.

Cordonnier sent me the order he wrote explaining why he was increasing the security level in the case of the CoxHealth lawsuit and why it was removed from CaseNet.

“WHEREAS, this Court, and the judges of the Thirty-First Judicial Circuit are aware from personal reports and experience, direct and circumstantial information, and intuition that members of the public, upon receiving a summons for jury service, do on occasion utilize CaseNet to investigate the case(s) upon which they may be called upon to serve …

“WHEREAS, an investigation via CaseNet conducted by a potential juror may occur at a time well in advance of the juror, or jury, being given any instruction or admonition from the Court prohibiting such research or investigation.”

Again, this is an order you would not have been able to read if you searched for the case at the time of trial because the case was removed from the online database.

Cordonnier emailed me: “I agree with you that having that specific order visible would perhaps deter some misunderstanding. It does not sound like the system will allow that, but they will investigate further.”

Cordonnier told me that when a member of the public, including reporters, has come to him to ask for a specific court document in a file he has made inaccessible online to the public, he has routinely released that document.

I asked if there was a study that shows that potential jurors do their own online research prior to being warned, if selected to a jury, to not read media accounts of the case.

He said no, he knows of no such study but that he has seen first-hand that it happens.

“We are not trying to keep the press out,” he told me. “I am trying to keep hundreds of jurors from going through the case file.

“We are not on different sides on this. We are on the same side.”

The judge was responsive and helpful. I believe he sees the importance of my efforts to inform the public on how a horrific crime has ultimately been resolved.

I’m not so sure about everybody else involved in this case.

This is Pokin Around Column No. 13.