IN-DEPTH |

It was just about 3:30 p.m. when the coach rolled in. Her team was already hard at work, studying game film. They’d just suffered a tough loss to West Virginia University — the mighty Mountaineers — and they were ready to learn from it.

Then it was time to practice. Two of the team members picked up their controllers and fired up a game of “Rocket League.”

Yes. Controllers, not balls, gloves and other equipment. Welcome to the world of collegiate esports, where teams of students play video games like “League of Legends, “Smash Ultimate” and “Valorant” competitively, for glory, prizes and scholarships. And they do so while building some of the same skills athletes learn in traditional sports like basketball, football and soccer.

Esports on the rise at OTC, MSU and Drury

Drury University is entering its fourth season of competition in this fast-growing sport. Missouri State, the largest school in the city, has a club of its own. And Ozarks Technical Community College is making its debut this fall. The Eagles are coached by Dr. Tiffany Ford, OTC department chair for computer information science.

“We were actually reviewing footage before Dr. Ford got here,” said Tyson Mead, a first-semester student from Willard. “We were looking at last night’s game. It was a loss, but we learned a lot, and we’re only going to keep getting better. The more we play together, the more we mesh, the more we work together, the better we’re going to get as a team. And I’ve already seen that over the last two games.”

Robert Morris University, located in Chicago, jumpstarted esports back in 2014 when it first started offering scholarships for talented “League of Legends” players. Schools across the nation, including Drury and OTC, have followed suit, with dedicated spaces for their teams to practice and compete in the National Association of College esports (NACe). Missouri State’s dedicated home for gaming, opened in 2021, is in Plaster Student Union’s Level 1 Games Center. It’s available for the student body as well as the school’s esports club, led by president Roman Thomas.

“It went from one school offering scholarships to eight, to 30 or 40 to now a couple hundred across the country,” said Michael Jones, head esports coach at Drury. “And there are eight or nine at least in Missouri alone.

“It’s no longer a niche thing anymore. When this started a lot of the media coverage that would come out, the whole story was ‘look how neat and novel this thing is.’ It’s still coming into the public consciousness for a lot of people. We’ve got a couple of years under our belt, and it is a legit college sport now. I’d say it’s taken the next step beyond being this new, strange thing. It’s pretty well established at hundreds of schools across the country.”

Esports audience now bigger than traditional sports

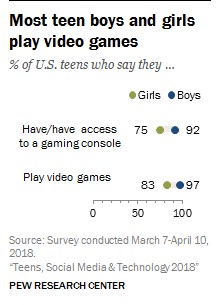

It shouldn’t be surprising. Video games are ubiquitous for young people in the United States. The Pew Research Center reported in 2018 that a majority of boys and girls play games, whether on a computer, game console or cell phone.

How much of a majority?

Try 90 percent of all teens, including 83 percent of girls and 97 percent of boys.

A staggering 84 percent of teens say they have access to a game console at home, while 90 percent say they play video games of any kind.

Mead was one of those young boys.

“I have a picture of me in diapers playing the original ‘Halo,’ so I’ve been playing for a pretty long time,” he said.

It’s no wonder, then, that esports is becoming big business. Competitions are streamed online worldwide, and the Missouri Scholastic Esports Federation (MOSEF) reported a projected 557 million in total viewership for 2021, more than every traditional U.S. sports league. An article in The Sport Journal reported esports had over $492 million in revenue in 2016. By 2021 those revenues were projected to hit $1.1 billion.

“Gaming attracts people at all levels,” said Ford. “You start gaming when you’re a kid, then it becomes a social activity — especially during COVID. That’s how a lot of these kids got through is hooking up with each other on Discord, talking, playing games.”

Gaming can lead to scholarships, improved quality of life for students

It can also be a way to help pay for college. OTC, like Drury, has scholarship money available for its team members.

“Not everyone gets one, so it’s those that are kind of rising to the top and taking leadership roles as maybe a team captain,” Ford said. “Some of it’s a little bit of a carrot to push themselves and think about their goals, and to come to practices and meet the commitment we’re asking of them. Overall that improves the team. If everyone’s doing their part, then the team gets better, and they play better.

“It also improves that student’s overall life. That scholarship is going to pay out to their account, so if they’re getting A+ (scholarship money) and they’re not paying tuition, that’s cash in their pocket. They can be using that for rent or buying more esports equipment for their house. All of them are talking about upgrading their computers at home because prices are starting to get a little better.”

Recruiting for esports in Springfield

Where are these esports athletes coming from? Everywhere. A scan of Drury’s 30-player roster shows hometowns in the Ozarks — like Ozark, Plato, Republic and Springfield — and as far away as California, New Mexico, Texas and Wisconsin. The recruitment of players varies from school to school. Jones is a full-time coach, so he works year-round to recruit.

“Most of the recruits I’m looking at are playing in high school, just like they are in any traditional sports,” Jones said. “So I’m building relationships with high school coaches; they’re referring kids to me. A lot of the best players on my team are coming out of high school esports, and specifically high school teams that are members of MOSEF, which is sort of the grassroots, nonprofit ran by teachers that organize high school esports competitions.”

Some players are self-recruited, like Mead. He was signing up for classes online when he saw an advertisement on the OTC homepage for the esports team. He joined the team on Discord — a social network and messaging app — and made connections with other team members.

“I was just like, ‘Am I dreaming? There’s no way I’m about to go to a college that has a brand new esports team. There’s no way,’” Mead said. “I hopped in (their Discord) and started talking to them, and we start getting things worked out. Fast forward five months later, here we are.”

It’s not always that easy. Jones also monitors websites like BeRecruited and Next College Student Athlete, better known as NCSA. It wasn’t always so organized, though. He compares the early years of recruiting to the Wild West.

“Some of my first recruits I found through friends, through team members or through the game itself,” Jones said. “I’d be playing with someone and I’d be like, ‘Hey, are you interested in going to college?’ Now it’s much more supported at the high school and, increasingly, at the middle school level. Many of them started as student clubs that have grown to look more and more like athletics teams. More schools are starting to offer stipends to teachers to be coaches, more resources, buying gaming-specific computers and peripherals instead of just relegating them to the existing computer lab.”

High schools invest in esports clubs

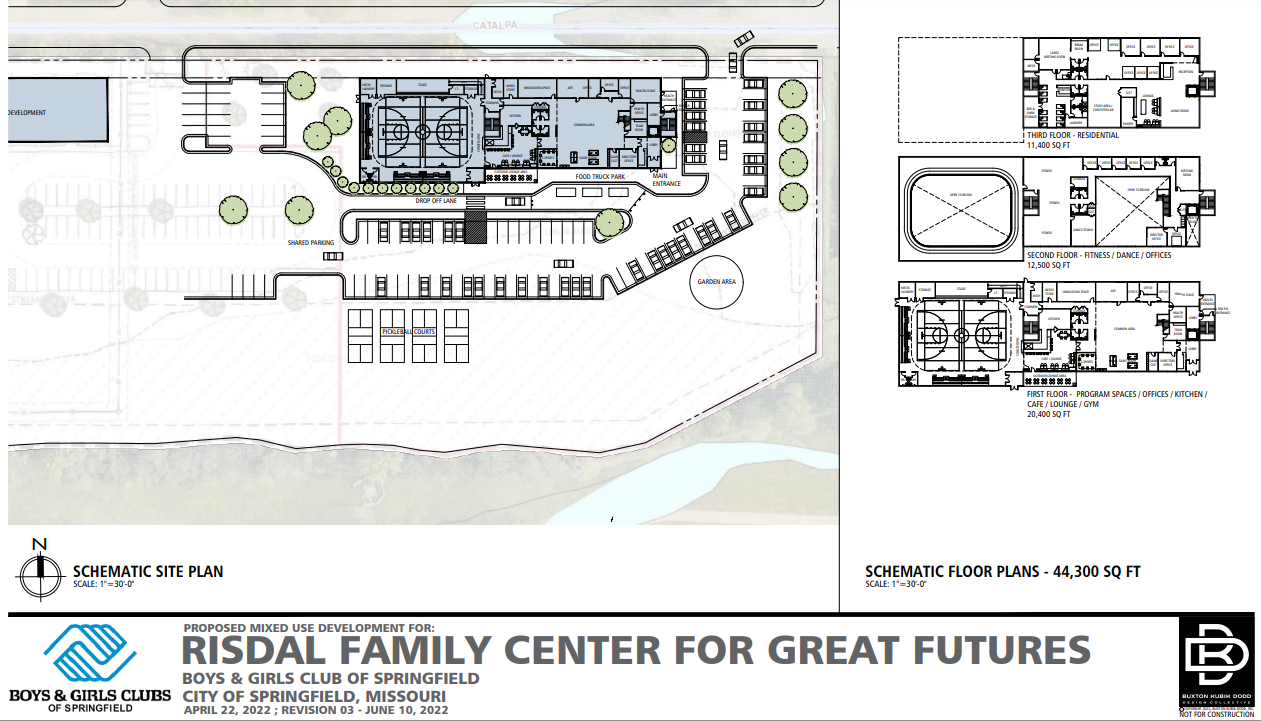

That kind of support is happening right here in the Ozarks. Schools like Branson, Hollister, Ozark, Republic and Sparta are involved in esports. Boys & Girls Club of Springfield’s new Risdal Family Center for Great Futures will include an esports lounge among other amenities.

And Springfield Public Schools is beginning a big investment to get its high schools and middle schools involved.

“We have had some esports clubs kind of randomly throughout our school system, student engagement clubs,” said Josh Scott, athletic director for SPS. “When we were looking to increase offerings, esports is right now the fastest growing sport in the world.

“We had periodically reached out and asked kids if you could have another extracurricular activity, what would it be — and esports was always in the top two to three, conservatively speaking. We looked at it and we will have a competitive team at each of the five high schools, with a coach leading the teams.”

Those teams are ramping up now, holding meetings and getting organized. The schools may not have the fancy dedicated esports lounges like the colleges do, opting to use a laptop-based system to game, but that hasn’t dampened interest.

“I know it only took five days and one of our coaches reached out to IT to ask for laptops for the kids,” Scott said. “They’re excited. We’re listening to our kids and bringing in an activity that is not only exploding on the college and high school level but worldwide. It’s not uncommon to see gamers coming to Springfield to game in our town. It’s pretty neat to be on the cutting edge of a growing sport.”

Are esports more or less accessible to students?

Not that there aren’t concerns. Equity is an issue, with some students unable to afford the equipment to game at home. While students might have access to an X-Box or Playstation game console, most college games are played on PCs — though esports lounges and school teams do help some. There’s also the issue of women in gaming.

“When I was a kid, video games were toys, and they were marketed to boys,” Jones said. “And if you look back at the video game marketing from the early 2000s, it’s apparent. So for a long time, this was just a space that the world said is not for girls and girls are not welcome. A lot of the most popular esports titles are these kinds of more masculine shooter games. And as a woman, if you pop into voice chat in some of these games, the odds of you getting harassed are pretty high. Now, to be fair, they’re pretty high for men as well, because there are always toxic players, and people are going to be jerks. But you can double or triple that if you’re a woman.”

Accessibility, however, is a strength of the sport.

“It is probably one of the most accessible sports,” Jones said, noting it is a co-ed activity. “There’s no inherent advantage that one gender would have over the other, so there’s no need to keep them separated as men’s and women’s. There’s also literal accessibility controllers so people with disabilities, who might be missing limbs or fingers, there are unique controllers and other setups that can allow them to play games. Not everyone can be on the football team, but literally anybody could be on the esports team.”

Bringing gaming ‘out of the basement and into shared spaces'

And so many different anybodies are joining esports teams, including students who might not be engaged in school otherwise.

“I like to say of all the recruits I talk to it’s about 50/50,” Jones said. “Half of them are really smart and hyper-involved in school, while the other half are also incredibly smart but just not involved in school because they never found a niche. They never found their own home.”

That was Mead. He said he dabbled in high school, trying track, baseball and speech and debate.

“They were cool and entertaining and I learned a lot from them, but nothing ever stuck,” Mead said. “I was a part of stuff all the time, but I never actually enjoyed any extracurricular stuff until now.

“I’m waking up every day excited to be here, which is something new for me. The entirety of K-12, I didn’t want to wake up and go to school. It wasn’t fun. Now, this is here and I have a reason to show up every day and be excited. It’s been amazing. … I’m here from 6 a.m. to, depending on the night, about 7 or 8 p.m. every single day.”

Those stories warm the hearts of coaches like Ford and Jones.

“Scholastic esports isn’t in place of other things, like traditional sports or ‘nerd sports’ like quiz bowl or speech and debate or band,” Jones said. “Esports just captures a different vertical of student that might not otherwise have been involved. Ultimately that helps them do better in school, it helps them make connections and that far outweighs any of the proposed downsides of gaming. I’m not one of those people that think video games cause violence, particularly in schools. I think the opposite. If we want to reduce violence in schools, we need to encourage students to approach these in a healthy way; bring it out of the basement and into this shared space where there are teammates and coaches to hold them accountable.”

Instilling sports values in gamers

Accountability is one of many lessons gamers learn from esports teams that are not that different than what they’d learn as an athlete in a traditional sport. Games are collaborative and require critical thinking and teamwork. There are also GPA standards and other guidelines in place that ensure students are working on their education while they play.

“Some of these (games) are like capture the flag, some are almost like soccer where you have goals at various ends, and there’s some kind of objective they have to work as a team to fulfill,” Ford said. “They’re working together here during practices on that communication, working together as a team, playing different roles. Think of it like soccer or football, right? You have various roles that you’re going to play on that team, various spots that are responsible for various things and it’s the same way in these games. So the coaches are really kind of helping them define that role, what are their responsibilities, how to communicate so that they can win those matches.”

And those matches are so much more than just a hobby for some of the athletes.

“We’re working our butts off in and out of the lab,” Mead said. “Last night, I worked with my ‘Valorant’ team outside of class. It’s like sports where you’re constantly working; you never stop. We’re always working to be better players, working to be better teammates and be a better team overall.”

Going pro: the career path

Just like other sports, there are opportunities for esports players to become professionals after college, turning a passion into paychecks.

“There are professional gamers now, just like there are professional basketball players,” said Jones. “And, yes, that is a possible career path for many people. But just like college athletics, the vast majority of college athletes don’t go on to be pros. It’s the same in college esports. But a lot of college athletes go on to work in college athletics, period. Either as coaches or in the front offices.”

That career path, too, is possible for gamers. As Ford says, esports are everything.

“You’ve got broadcasting, making sure the transitions are smooth and having that on-air host so — like when you listen to soccer or baseball — you have that commentary,” she said. “Then you have the technical background to put the PCs together, to put those streams together, to build graphic overlays, to do the marketing and social media.

“Then, on the pro side, you’ve got business managers, people talking about sponsorships and brand deals. It just branches out into everything. Esports is really a path. If you like games, you can play the games. If you like esports and you want to support gaming, but you’re a marketing person, there’s a spot for you. You’re an accounting person? There’s a spot for you.”

And there’s a spot for you at more schools than ever.